The Meadows:

DONELLA and Dennis Meadows are trying to come up with global solutions to global problems. "The idea which is the focus of much of our personal and professional lives is that the steady state society with equilibrium ... is the viable one over the long run," says Dennis Meadows, who holds appointments in both engineering (Thayer School) and management (Tuck School). The Meadows were the principal authors of Limits to Growth, a book which won the 1973 German Peace Prize and has sold more than two million copies. Limits to Growth uses computer models to predict that at present exponential growth rates in population, industrialization, pollution, food production, and resource depletion society will collapse economically and socially during the 21st century. What has been the impact of Limits to Growth? "It's been four years since the book came out. It was not earth shattering," says Donella Meadows, who prefers to be called Dana. She is an assistant professor of environmental studies. "A lot of people had those ideas. I don't think you can assess whether the book had an effect or not."

Yet the book has had an effect on the Meadows themselves. They are people of catholic interests, yet everything seems to converge on the ideas in Limits to Growth. They both tend to interlard conversation with the Limits to Growth vernacular: computer models, long-term perspectives, the equilibrium level, systems, positive feedback loops, negative feedback loops ("everything is connected to everything else"). "There is no question," Dana Meadows says, "that we will spend the rest of our lives working on these problems. A lot more work needs to be done on them."

The Meadows live on a 60-acre farm in Plainfield, New Hampshire, a hamlet 15 miles south of the College, where residents still assemble in the town hall on Saturday evenings to play bingo. They came to Dartmouth in 1972 from M.I.T. and the Club of Rome's Project on the Predicament of Mankind, directed by Dennis Meadows, which produced Limits to Growth. "Have you ever read the Mother Earth News?" Dennis Meadows interjects into a discussion about something else. "The MotherEarth News strengthened our resolve to get the hell out of Cambridge and come up here." They are, for the most part, vegetarians. They are childless. They share their house and farm with about four people ("that's the steady state number") who in turn share expenses, cooking, cleaning, and farm work on Saturdays.

They are not so much owners as custodians of the land. Dennis Meadows is not, as he'll tell you, "just a college professor running a hobby farm," and he'll show you the calluses that come from handling a 45-pound chain saw all day to prove it. On one Saturday morning in July, he was up early to work with a half dozen students clearing a boggy field that the farm's previous owner had let fall into disrepair. The Meadows are building a stock watering pond for sheep that will graze in the field (Dana Meadows spins sheep wool). They are also planning to restore a neglected mill on their property. There is a list of 19 other projects of "equal magnitude" posted in the pantry. Dana Meadows was in the organic garden below the house, uplifting vegetable plants and planting new ones in their place. "I have a Ph.D. in biology," she says, "but I have learned more about biology in my organic garden. . . . I've also learned more about chemistry in my organic garden." She keeps track of her crop rotation scheme on a sheet of paper posted in the kitchen.

The Meadows don't like to talk about their personal lives when it is for public consumption. Dennis Meadows doesn't think it is anybody's business that he doesn't own a television set ("Why should I own a television set?"), that he peruses Sears catalogs looking for bargains, that he plays darts, that there is a sunflower painted on the side of an outhouse behind his house — details that he terms "the minutiae of our private lives." When he wants to intimidate a questioner, he poses rhetorical questions. "Who benefits? What do we get out of it? Enough people already have their names in print. Ego satisfaction is the furthest thing from our considerations." He doesn't want to call his living arrangement communal because of the "stereotypical image" people have of communes. He decries the media as "just entertainment."

"The way we live places a high emphasis on the material and energy consumption in the steady state," he says. Why, then, doesn't he want to talk about their lives? "At some point we are going to work on selling our general life-style. We think it is the most satisfying way to serve our ecological and sociological goals. ... At some point, a goal could be served by talking about our private lives. At the moment, however, there is no goal to be served."

The Meadows don't talk in terms of "I." It is almost always "we." Sometimes the "we" refers to Dana and Dennis Meadows, sometimes to what they call "our group" — 15 graduate students, undergraduates, and visiting professors at the College. The Meadows have the unusual privilege of working in adjoining offices on the third floor of the Murdough Center, surrounded by the hurly-burly of various projects they are working on with "our group" and other students. There is a computer terminal located across the hallway from their offices.

They are both magna cum laude graduates of Carleton College. They both taught at M.I.T. before coming to Dartmouth. She is 35 years old, he is a year younger.

The Meadows are remarkably homogeneous in their thinking, not just in environmental matters, but seemingly in all aspects of life. They use words like "exquisite" and "nifty." Dennis Meadows is more aggressive than Dana Meadows, more in a hurry to get somewhere. He doesn't amble, he moves. When he plays ping-pong, he attacks the ball. He likes to chop wood. He wants people to be efficient. Dana Meadows smiles a lot, he doesn't. Her office is smaller and less disordered than his.

The Meadows aren't the type of people who idly ask if you know acquaintances of theirs. They don't discuss the weather. They talk about important matters. "I find it useful," Dennis Meadows says sententiously, "to divide people into three categories. First, there are people who talk about other people. There are people who talk about things. And there are people who talk about ideas." The Meadows like cerebral discussions. They are not cynical or pessimistic when they talk — nor is Limits to Growth a manual for doomsayers. They are people who ask questions that begin "Why do you suppose ... ?" and who wonder "Why is that? Why should it be that way?" They ask questions because they are seeking answers. They know that wrongs are being committed, and they want to persuade others that destructive wrongs must be made right.

While eating lunch with a group of students, Dana Meadows talks about a protest against a nuclear power plant that is to built on the New Hampshire coastline. Dennis Meadows points to where a public road borders his property and says that the previous spring they picked up 500 discarded cans there. Earlier that day, some discolored Budweiser and Sheaffer beer cans had been unearthed in his field. As a teenager, he says, he didn't cruise around drinking beer and chucking the empties. "It makes me so mad. Somehow, to litter like that seems to be the epitome of our society. ... It's the idea that here, here it is, and now it's gone and I don't have to worry about it any more." While driving past a shopping center in West Lebanon, he laments about "toys that don't have the least bit of subtlety any more" and "mile after plastic mile" of merchandise: "The shopping center squeezes out the small store owners. Have you ever seen Lebanon?" He talks about how the HUD program to rejuvenate the town foundered when the shopping center was built just off Interstate 89, drawing business from the downtown area, and about the poor and elderly who have "no way to get out to the big store, so they're hurt."

The Meadows are relaxing in the kitchen on a Saturday evening following a day of work on the farm. Dennis Meadows will be flying out to California the next day. He has put together a dinner of vegetable soup, layered corn bread, and deviled eggs. The eggs are from the chicken coop behind the house, the vegetables from the organic garden. Dana Meadows made the corn bread. He is doing most of the talking. Do you believe in God? a visitor asks him. He says he doesn't. Then he clarifies. "It depends on the image of God you're talking about. These images vary from the literal interpretation of the Bible of some guy above the clouds with wings to almost the primitive cultural conceptions of God the trees, the plants, the animals - all of which go to define respectable behavior. Somewhere along the way I find myself somewhere in the middle, closest, I suppose, to the Buddhists. ..."

He is expansive. He leans back in his chair by the window, eyes partially closed, hands interlocked behind his head, as he tends to do when he is articulating his ideas or thinking about important matters. Norwegian music is playing over the stereo. He looks out the window, across the back porch, the organic garden, toward where the sun has receded behind the hillock that borders his property. He says he has "other functions" that replace the "functions played by God." He continues: "You are always going to try to do better than you are doing. You have an obligation to do better." Man, he says, should endeavor to reach his fullest potential. "At one point I was very religious — I was one of these guys who would go out and try to proselytize old ladies in old folks' homes. Then I went through a period of not thinking about God. It seems to me that the only thing that lasts is ideas. My life is to increase the stock of knowledge and to disseminate that knowledge." He pauses to point at a bird perched outside the window.

Dana Meadows says they are going to become Buddhists.

"The backbone of Buddhism," Dennis Meadows says, "is that we rely on our own resources. I don't know a lot about Buddhism, but I do know a lot about the Zen Buddhist practices in this country ....

"It's a different ideology. It's more tolerant than Christianity. It's the equilibrium religion. ..."

"Buddhism is a more systematic religion than Christianity," Dana Meadows says. "Christianity is a subset of Buddhism." She smiles, pleased with the cleverness of the thought. "Buddhism is at the far right, if you remember the part at the beginning of our book that talks about human perspectives. The Buddhists believe that what you do doesn't need to bear fruit for 150 years. Buddhism is about how man can live together with nature." It is all echoed in the Limits to Growth philosophy.

Dana Meadows assigned Zen and theArt of Motorcycle Maintenance ("it's about how to live life — how to carry on, how to do things") as background reading for the environmental ethics course she taught during Dartmouth's summer term. She wants her students to know how to make decisions about nuclear power, about industry. "Question, question, question. Don't accept that from me! That's a theory," she told another summer class, this one in population theories. "She asks a lot of questions — questions that really can't be answered," commented a student in the class. Dana Meadows is expressive when she teaches, always motioning with her hands. She smiles when she makes a point, yet she is earnest. She tells the class she wants to take it "further and further from knowledge to revelation." She advises students to be skeptical of statistics. She has her biases. "I'm going to talk about three population theories. I don't believe any of them. But you should have a knowledge of them."

Why does she teach? "I teach because I learn from teaching." She smiles. "As soon as I stop doing that I'll stop teaching. We all learn together." Last spring, Dana Meadows walked into the first meeting of an environmental policy formulation class and told the approximately 30 students they would have ten weeks to draft an energy policy for the state of Vermont. They wrote a 600-page report and presented their policy recommendations to the state government in Montpelier. The year before, she had the same class project the effect a proposed $220 million pulp mill would have on the upper Connecticut River Valley, thereby arousing the pique of William Loeb, a New Hampshire newspaper publisher not known to be friendly to "pointy-headed liberals." She works with the environmental policy class, dispenses advice, and brings in experts to consult with the students. The students utilize computer models, surveys, and graphs to formulate a policy. "It's incredible what you have to know to take the course," she says. "I learn a lot from the course."

In the classroom, the Meadows do not want to "breed dilettantes ... who just know the words," as Dennis Meadows puts it. He is collaborating with an undergraduate on an introductory text for a course in systems dynamics. Do they frequently plan classes with students? "Only with the good students," they both say. They spend a lot of time with students, and are on a first name basis even with those they have just met. Some who take classes from the Meadows catch the Limits toGrowth contagion, others don't. And those who work with them seem to embrace the same values, concerns, approach to living. After seeing a film about death with the population theories class, a student was moved to comment, "It's not just numbers. People really do die" - and he meant it. One undergraduate who took the environmental policy course last spring and has worked on the Meadows' farm dismantled his bicycle part by part and then put it back together as preparation for a test in a summer term calculus course.

"There are quite a few committed ones. They're going to go out and do all kinds of things in life," say Dana Meadows. She is presently working on agricultural policy with graduate students. Dennis Meadows is editing a book of essays entitled Alternatives to Growth.

Seven years ago — before the Club of Rome, Limits to Growth, the bucolic homestead in New Hampshire — the Meadows went to India and Ceylon on a travel and research program. They saw hunger and overpopulation. How can India and the United States exist in the same world they wondered. They wanted to know why what they had seen happens. Several years later they set forth some answers in Limits to Growth.

Today, they are two of the best known futurists. Yet they continue to pursue global problems unobtrusively and unostentatiously. They are not the kind of people, as Dana Meadows says, who will go on television and "scream at people. That is not our way of doing things. We are pretty good at computer modeling. Not everyone else is good at computer modeling. So that's what we do. We simply make up a piece of the puzzle."

How does it feel to know you're right, to know what you say is important, and yet to see people live their day-to-day lives ignorant of your warnings? "It has ceased to surprise us," says Dana Meadows. "We're not laboring under the illusion that we will stop the world and turn it around 180 degrees. Growth is embedded in our society. The reasons why people have babies, the reasons why people build factories ... are not illogical but they are unfortunate."

She is earnest, but not solemn. She keeps breaking into smiles as she talks. "As we become older, we become more patient, more humble. We'll do what we can, maybe succeed, maybe not."

Dana and Dennis Meadows: living and working for a world in equilibrium

Pierre Kirch '7B, from Hollister, California, is one of this year's undergraduateeditors.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSeeing Farther than the Green

September 1976 By BLISS K. THORNE and NANCY DECATO -

Feature

FeatureHarvard Myths About Dartmouth

September 1976 By ERICH SEGAL -

Feature

FeatureHANOVER SUMMER

September 1976 -

Books

BooksNotes on a common bond: the federal city, that summer in Philadelphia, Essex County in revolt, and disaster in Ohio

September 1976 By R.H.R. -

Article

ArticleMeasured Quantities

September 1976 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926's 50th

September 1976 By H. DONALD NORSTRAND

Pierre Kirch

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSTUDENT LOANS

December 1956 -

Feature

FeatureThey Also Went Forth

JUNE 1977 -

Feature

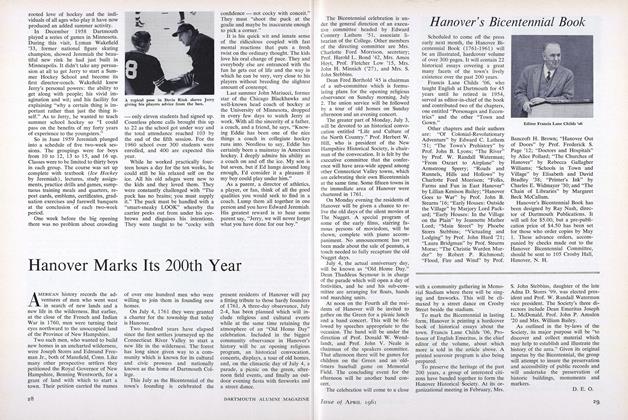

FeatureHanover Marks Its 200th Year

April 1961 By D.E.O. -

Feature

FeatureFour Steps Forward in Biology

JUNE 1968 By PROF. RAYMOND W. BARRATT. -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO RUMBA

Sept/Oct 2001 By ROBERT TIRRELL '45 -

Feature

FeatureMaking the Normal Less Normal

NOVEMBER 1989 By Warner R. Traynham '57