Notes on a common bond: the federal city, that summer in Philadelphia, Essex County in revolt, and disaster in Ohio

September 1976 R.H.R.Notes on a common bond: the federal city, that summer in Philadelphia, Essex County in revolt, and disaster in Ohio R.H.R. September 1976

It has been almost too much, this Bicentennial summer. If we couldn't be there, anywhere, in person our surrogate eye the TV camera flashed an incredible number and variety of spectacles into our living rooms. The instantaneous mirror was held up to us all for us all. The images were there right in front of us, each spectacle replete with its own sense of history, symbolism, irony, or, occasionally, inanity. And it was overwhelming: those magnificent tall ships sailing (never mind against the wind) up New York Harbor; the queen of England making genteel ex post facto amends to J. Adams and Co. beneath the Old State House in Boston; the Battle of Gettysburg recreated before our eyes (and to hell with the irrelevance); Old Ironsides, which, astonishingly, lost none of her ancient dignity by having to be propelled, minus sails, through Boston Harbor by tugs; the Statue of Liberty stolid behind the hundred-tongued dazzle of multiple fireworks bursts; the countless thousands of our tricorn-hatted friends and neighbors bent more or less raggedly on recreating the 18th century military ambiance with shouldered flintlocks, the slow step, and the shrill of fife.

But for all their bigness the TV-oriented Bicentennial spectacles may be more evanescent, I suspect, than many of the books which our 200th summer has also brought. For the books give us time to think about ourselves, our national accomplishments, our shortcomings; they hold up the mirror to the eye of contemplation. We haven't seen all the Bicentennialinspired books, certainly, and many of those that have come across our desk have been examined in past issues. Among the more interesting which this summer has brought, however, are two dealing with the quintessentially American cities of Washington and Philadelphia.

The Federal City: Plans and Realities, by Frederick Gutheim and Wilcomb E. Washburn '48, was published jointly by the Smithsonian Institution, the National Capital Planning Commission, and the Commission of Fine Arts (Smithsonian Institution Press Publication No. 6161). It is in part the catalogue of an exhibition which will be open to public view for the next two years in the Great Hall of the Smithsonian Institution Building. But to call it only a catalogue demeans the book. Its subject is the planning and development of the city of Washington beginning with the initial neoclassical conception of the Federal City of Major Pierre L'Enfant in the 1790s and ending with the projections of present-day planners for the year 2000.

With all respect to the authors of the text, the interested layman will no doubt find the illustrations the real eye-catchers. For them Washburn, director of the Smithsonian Office of American Studies, drew lavishly on the archives of the Smithsonian and the Library of Congress and chose several dozen maps and views, which include the first published plan of the city (1792), the L'Enfant plan (1793), lithographs of 1852 and 1862, and numerous photographs of famous buildings and areas from the mid-19th century to the present. Though the übiquitous word "Bicentennial" is nowhere mentioned, this illustrated history of our unique Federal City affords more cause for quiet American pride in this 200th summer than all our rockets' red glare.

Of a completely different order, but no less impressive, is The Founding City, edited by David R, Boldt '63 (Radnor, Pa., Chilton Book Co., 1976). Though an occasional ill-natured Bostonian may dispute it, Philadelphia is the Founding City. Far from alabaster, it nonetheless gleams with the sheen of the past. And this book catches it all. Boldt's book is an agglomeration of "bits and pieces" (the phrase is his own); it is, in fact, a gathering of special supplements which have been issued by the Philadelphia Inquirer over the past year. The aim is ambitious: to recreate a small point in history when in 1776 "The aspirations of a continent became focused in those warm summer days in Philadelphia, the Founding City." The bits and pieces are just that: they include the recreation of a single day in the lives of an average Philadelphia family in that former summer of '76; biographical sketches of Franklin, Paine, Morris, Penn, and others; studies of the Colonial press, painting, literature, music; analyses of Toryism and Loyalists; accounts of major generals and battles of the Revolution. ...

Incredibly, it all works. The bits and pieces at first counterpoint one another, then fall into place, then finally cohere. Whether or not the editors of the Inquirer aimed at so solemn a goal, they have in fact achieved one: they have put together the stuff of social history. That a newspaper undertook - and underwrote - this project testifies to the imagination and publicspiritedness of its editorial directors; that a newspaper staff brought the project off with such skill is as unusual as it is commendable. Which is why, I suppose, in Philadelphia nearly everyone reads the Inquirer.

A Massachusetts county has been subjected to a more traditional kind of historical scrutiny in A County in Revolution, by Ronald N. Tagney '62 (Cricket Press, Manchester [Mass.], 1976. $8.95). In carefully documented detail Professor Tagney recounts the activities of the citizens of Essex County, Massachusetts, before and during the Revolution. With such North Shore towns as Lynn, Salem, Marblehead, Gloucester, and Newburyport within its borders, it is not surprising that Essex County's major contribution to the Revolution was on the sea. General Washington's Continental Navy was born along the Essex County shore as, sailing from such ports as Beverly and New-buryport, the first commissioned vessels under an American ensign disrupted British seaborne supply lines and captured desperately needed ordnance for the rag-tag Continental Army. John Manley, perhaps America's first genuine naval hero, was from Marblehead; Beverly was America's first naval base; and Salem and New-buryport were its major ports for privateers. Professor Tagney's book is at its best when recounting the exploits of the men and ships of this sea-faring county.

If the connection between the seamen of long-settled, civilized Essex County and the Indian fighters of the primitive, sparsely settled Ohio frontier appears tenuous, it should seem less so after reading Fort Laurens, 1778-79: TheRevolutionary War in Ohio, by Thomas J. Pieper and James B. Gidney '36 (Kent State University Press, 1976. $7.95). For contrary to popular assumptions, the War of Independence was not entirely confined to the seaboard. Erected on the banks of the Tuscarawas River in the fall of 1778, Fort Laurens resulted from Washington's two-part strategy to secure his western frontier flank. He established the fort not only to protect the friendly Delaware Indian tribes but also to serve as a stepping stone on the way to what he hoped would be the capture of Detroit, the corner stone of British power in the West. Both aims came to nothing; the venture was an exercise in futility, for the ill-conceived fort was abandoned after little more than a winter's existence. That single cruel winter which outdid even Valley Forge, however, when the starving handful of men who garrisoned Fort Laurens boiled beef hides and moccasins for food, fought off a British-Indian attack, and died - a few of them - in squalid misery is a neglected small chapter of the Revolutionary War which by this small book is placed properly in the context of the larger struggle for independence.

At an accelerated pace this Bicentennial year, new perspectives are gained. From finely written books as different as.Gidney's Fort Laurens and Boldt's Founding City one senses the authenticity of history, the imaginative recreation of things past. Perhaps the epigraph which Boldt chose for his book expresses it best: "The poetry of history lies in the quasi-miraculous fact that once, on this earth, on this familiar spot of ground, walked other men and women as actual as we are today, thinking their own thoughts, swayed by their own passions — but now all gone, one generation vanishing after another, gone as utterly as we ourselves shall shortly be gone, like ghosts at cockcrow."

Our review of Volume II of the Daniel Webster papers (June issue) failed to note the contribution of Harold D. Moser, associate editor, who under the direction of editor Charles M. Wiltse supervised the assembling and editing of this volume. The unbound proof sheets supplied to our reviewer apparently did not contain this information. We regret the omission of well-deserved credit.

"I have full cause of weeping, but thisheartShall break into a hundred thousandflawsOr ere I'll weep. O fool! I shall gomad." — Gobin Stair's illustration for the "O! reasonnot the need" soliloquy toward the end ofAct II of King Lear.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSeeing Farther than the Green

September 1976 By BLISS K. THORNE and NANCY DECATO -

Feature

FeatureSteady State

September 1976 By Pierre Kirch -

Feature

FeatureHarvard Myths About Dartmouth

September 1976 By ERICH SEGAL -

Feature

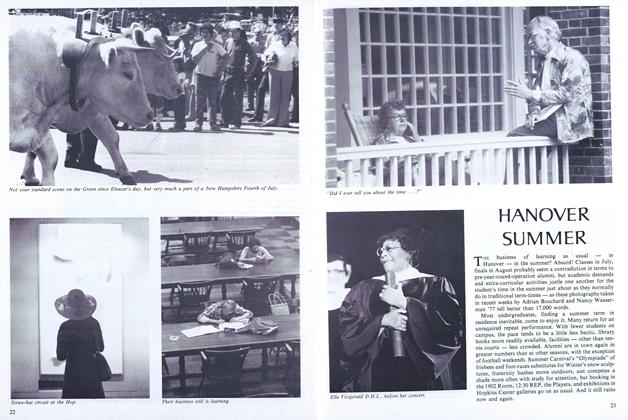

FeatureHANOVER SUMMER

September 1976 -

Article

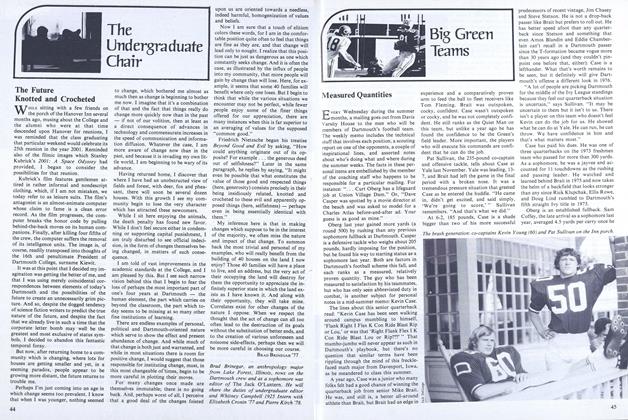

ArticleMeasured Quantities

September 1976 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926's 50th

September 1976 By H. DONALD NORSTRAND

R.H.R.

-

Books

BooksNotes on a humanizing craft, a National Book Award, the Adamses, Avant-garde dancers, Irving Howe's tribute, and the Texas nation.

June 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksMonticello to Montmartre

November 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on a Pulitzer not given and on Dr. Bob, a gruff, humane Yankee who helped found AA

JUNE 1977 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksObserving Life

JAN./FEB. 1978 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on a Yale man's journal and the 'elbowing self-conceit of youth.'

MARCH 1978 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksLooking Out for #1

September 1980 By R.H.R.

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Publications

February 1935 -

Books

BooksA SENTIMENTAL JOURNEY.

JUNE 1970 By GEORGE M. YOUNG JR. -

Books

BooksBlack Sheep

March 1977 By HENRY L. TERRIE JR. -

Books

BooksOUTPOSTS OF THE PUBLIC SCHOOL

April 1939 By Highly Recommended, Louis P. Benezet '99 -

Books

BooksBIG BUSINESS – YOUR LIFE WITHIN IT.

October 1974 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksGREEN EGGS AND HAM.

December 1960 By MAUDE D. FRENCH

R.H.R.

-

Books

BooksNotes on a humanizing craft, a National Book Award, the Adamses, Avant-garde dancers, Irving Howe's tribute, and the Texas nation.

June 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksMonticello to Montmartre

November 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on a Pulitzer not given and on Dr. Bob, a gruff, humane Yankee who helped found AA

JUNE 1977 By R.H.R.