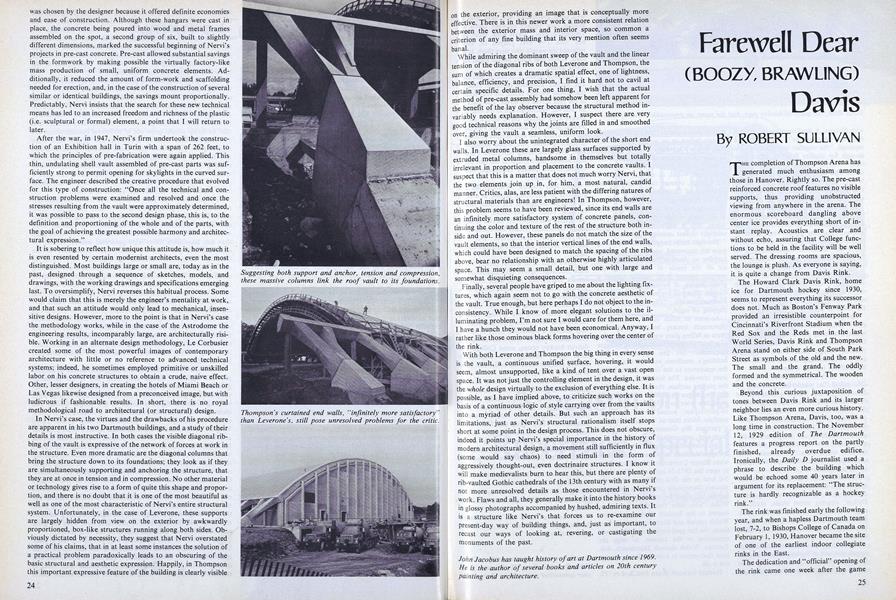

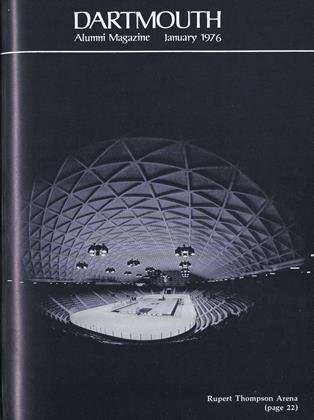

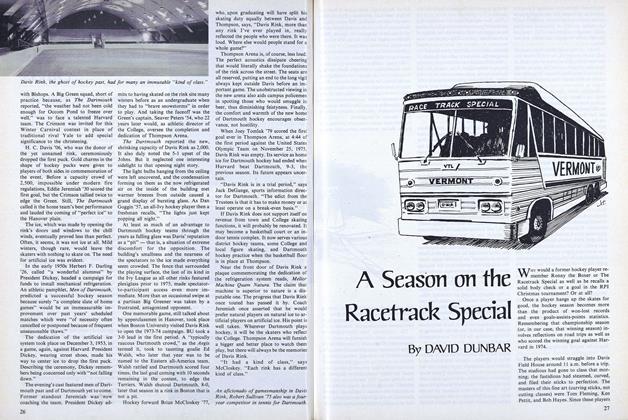

THE completion of Thompson Arena has generated much enthusiasm among those in Hanover. Rightly so. The pre-cast reinforced concrete roof features no visible supports, thus providing unobstructed viewing from anywhere in the arena. The enormous scoreboard dangling above center ice provides everything short of instant replay. Acoustics are clear and without echo, assuring that College functions to be held in the facility will be well served. The dressing rooms are spacious, the lounge is plush. As everyone is saying, it is quite a change from Davis Rink.

The Howard Clark Davis Rink, home ice for Dartmouth hockey since 1930, seems to represent everything its successor does not. Much as Boston's Fenway Park provided an irresistible counterpoint for Cincinnati's Riverfront Stadium when the Red Sox and the Reds met in the last World Series, Davis Rink and Thompson Arena stand on either side of South Park Street as symbols of the old and the new. The small and the grand. The oddly formed and the symmetrical. The wooden and the concrete.

Beyond this curious juxtaposition of tones between Davis Rink and its larger neighbor lies an even more curious history. Like Thompson Arena, Davis, too, was a long time in construction. The November 12, 1929 edition of The Dartmouth features a progress report on the partly finished, already overdue edifice. Ironically, the Daily D journalist used a phrase to describe the building which would be echoed some 40 years later in argument for its replacement: "The structure is hardly recognizable as a hockey rink."

The rink was finished early the following year, and when a hapless Dartmouth team lost, 7-2, to Bishops College of Canada on February 1, 1930, Hanover became the site of one of the earliest indoor collegiate rinks in the East.

The dedication and "official" opening of the rink came one week after the game with Bishops. A Big Green squad, short of practice because, as The Dartmouth reported, "the weather had not been cold enough for Occom Pond to freeze over well," was to face a talented Harvard team. The Crimson was invited for this Winter Carnival contest in place of traditional rival Yale to add special significance to the christening.

H.C. Davis '06, who was the donor of the yet unnamed rink, ceremoniously dropped the first puck. Gold charms in the shape of hockey pucks were given to players of both sides in commemoration of the event. Before a capacity crowd of 2,500, impossible under modern fire regulations, Eddie Jeremiah '30 scored the first goal, but the Crimson tallied twice to edge the Green. Still, The Dartmouth called it the home team's best performance and lauded the coming of "perfect ice" to the Hanover plain.

The ice, which was made by opening the rink's doors and windows to the chill winds, eventually proved less than perfect. Often, it seems, it was not ice at all. Mild winters, though rare, would leave the skaters with nothing to skate on. The need for artificial ice was evident.

In the early 1950s Herbert F. Darling '26, called "a wonderful alumnus" by President Dickey, headed a campaign for funds to install mechanical refrigeration. An athletic pamphlet, Men of Dartmouth, predicted a successful hockey season because surely "a complete slate of home games" would be an immeasurable improvement over past years' scheduled matches which were "of necessity often cancelled or postponed because of frequent unseasonable thaws."

The dedication of the artificial ice system took place on December 3, 1953, in a game, again, against Harvard. President Dickey, wearing street shoes, made his way to center ice to drop the first puck. Describing the ceremony, Dickey remembers being concerned only with "not falling down."

The evening's cast featured men of Dartmouth past and of Dartmouth yet to come. Former standout Jeremiah was now coaching the team. President Dickey admits to having skated on the rink site many winters before as an undergraduate when they had to "brave snowstorms" in order to play. And taking the faceoff was the Green's captain, Seaver Peters '54, who 22 years later would, as athletic director of the College, oversee the completion and dedication of Thompson Arena.

The Dartmouth reported the new, shrinking capacity of Davis Rink as 2,000. It also duly noted the 5-1 upset of the Johns. But it neglected one interesting sidelight to that opening night story.

The light bulbs hanging from the ceiling were left uncovered, and the condensation forming on them as the now refrigerated air on the inside of the building met warmer breezes from outside caused a grand display of bursting glass. As Dan Goggin '57, an all-Ivy hockey player then a freshman recalls, "The lights just kept popping all night."

At least as much of an advantage to Dartmouth hockey teams through the years as falling glass was Davis' reputation as a "pit" — that is, a situation of extreme discomfort for the opposition. The building's smallness and the nearness of the spectators to the ice made everything seem crowded. The fence that surrounded the playing surface, the last of its kind in the Ivy League as all other rinks featured plexiglass prior to 1975, made spectator-to-participant access even more immediate. More than an occasional swipe at a partisan Big Greener was taken by a frustrated, antagonized opponent.

One memorable game, still talked about by upperclassmen in Hanover, took place when Boston University visited Davis Rink to open the 1973-74 campaign. BU took a 3-0 lead in the first period. A "typically raucous Dartmouth crowd," as the Aegis termed it, took to taunting goalie Ed Walsh, who later that year was to be named to the Eastern all-America team. Walsh rattled and Dartmouth scored four times, the last goal coming with 10 seconds remaining in the contest, to edge the Terriers. Walsh shutout Dartmouth, 8-0, later that season in a rink in Boston that is not a pit.

Hockey forward Brian McCloskey '77, who, upon graduating will have split his skating duty equally between Davis and Thompson, says, "Davis Rink, more than any rink I've ever played in, really reflected the people who were there. It was loud. Where else would people stand for a whole game?"

Thompson Arena is, of course, less loud. The perfect acoustics dissipate cheering that would literally shake the foundations of the rink across the street. The seats are all reserved, putting an end to the long vigil always kept outside Davis before an important game. The unobstructed viewing in the new arena also aids campus policemen in spotting those who would smuggle in beer, thus diminishing feistyness. Finally, the comfort and warmth of the new home of Dartmouth hockey encourages observance, not hostility.

When Joey Tomlak '79 scored the first goal ever in Thompson Arena, at 4:44 of the first period against the United States Olympic Team on November 25, 1975, Davis Rink was empty. Its service as home ice for Dartmouth hockey had ended when Harvard beat Dartmouth, 9-3, the previous season. Its future appears uncertain.

"Davis Rink is in a trial period," says Jack DeGange, sports information director for Dartmouth. "The edict from the Trustees is that it has to make money or at least operate on a break-even basis."

If Davis Rink does not support itself on revenue from town and College skating functions, it will probably be renovated. It may become a basketball court or an indoor tennis complex. It now serves various district hockey teams, some College and local figure skating, and Dartmouth hockey practice when the basketball floor is in place at Thompson.

Near the front door of Davis Rink a plaque commemorating the dedication of the refrigeration system reads, MeliorMachina Quam Natura. The claim that machine is superior to nature is a disputable one. The progress that Davis Rink once touted has passed it by. Coach Jeremiah once asserted that he would prefer natural players on natural ice to artificial players on artificial ice. His point is well taken. Wherever Dartmouth plays hockey, it will be the skaters who reflect the College. Thompson Arena will furnish a bigger and better place to watch them play, but there will always be the memories of Davis Rink.

"It had a kind of class," says McCloskey. "Each rink has a different kind of class."

Davis Rink, the ghost of hockey past, had for many an immutable "kind of class."

An aficionado of gamesmanship in DavisRink, Robert Sullivan '75 also was a four-year competitor in tennis for Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOur Way in the World: A Conversation with John Dickey

January 1976 -

Feature

FeatureNervi's Concrete Aesthetic

January 1976 By JOHN JACOBUS -

Feature

FeatureA Season on the Racetrack Special

January 1976 By DAVID DUNBAR -

Article

ArticleA Reasonable Balance?

January 1976 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

January 1976 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE -

Article

ArticleAll This And Coffee, Too

January 1976 By CLIFF JORDAN '45

ROBERT SULLIVAN

Features

-

Feature

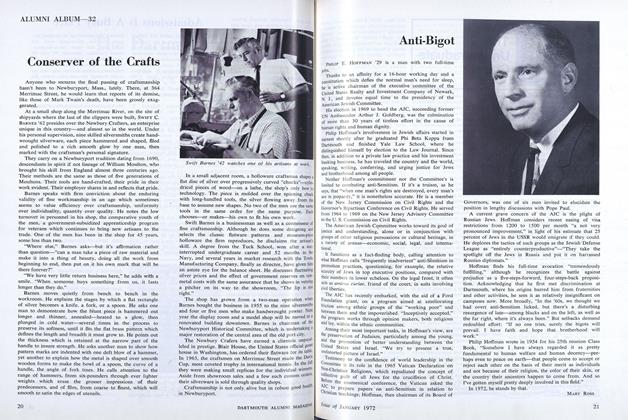

FeatureConserver of the Crafts

JANUARY 1972 -

Cover Story

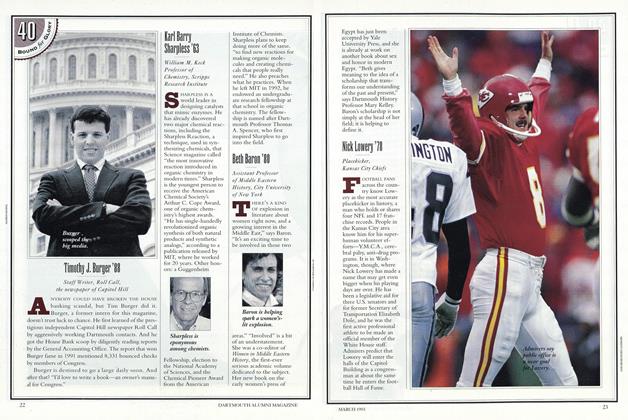

Cover StoryBeth Baron '80

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureNotes on the New Europe

NOVEMBER 1966 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47 -

Feature

FeatureEight Graduates of Dartmouth Who Were First College Presidents

JUNE 1969 By John Hurd '21 -

Feature

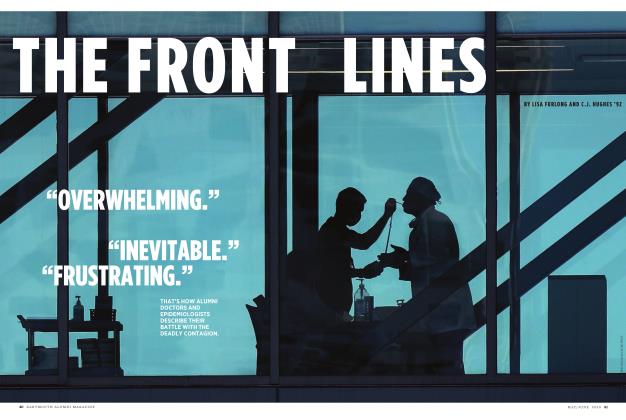

FeatureThe Front Lines

MAY | JUNE 2020 By LISA FURLONG, C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May/June 2005 By Olivia Britt '00