I do not choose to talk about the outlook for 1976. That will take care of itself. Self-designated prognosticators of future political events invariably prove wrong. Once is enough for me.

This is the year of the Bicentennial. Based upon my reading, last year (and in terms of our close friends, the Chinese) can be designated the Year of the Shark. My topic is more closely akin to the Year of the Shark. My ultimate thesis is that it is not just power which corrupts or that absolute power corrupts absolutely, but rather that the anticipation of power, the quest for power, can be equally corrupting.

This brings me to Carcharodon carcharias - the White Death Shark - described as the fiercest and most fearsome predator on earth. Growing to a length of more than 30 feet, always on the prowl and always hungry, it will attack anything that appears even remotely edible. It creates a savage environment.

So it is with presidential primaries. Striving for the appearance of a family get-together at Thanksgiving, the party primary is in reality an extraordinary quest for power; when its cover is stripped away, its true nature is exposed - ferocious combat. Sometimes presidential primaries are without genuine purpose. They are like the White Death Shark itself, which lacks the flotation bladder common to other fish and the fluttering flaps to push oxygen-bearing water through its gills. Both sharks and candidates and their respective parasites survive only by movement, and if they once stop, for whatever reason, they sink to the bottom and die of anoxia.

If this observation about the presidential primaries seems unkind, I believe it is nonetheless moderately accurate. Quite ordinary people possessed of essentially decent instincts lose perspective. Candidates themselves are too easily turned into mouthpieces for positions they have had little time to study and even less time to digest. They are unaware of the consequences of positions they take. If they take care, if they shun the facile use of symbols they are accused of indecisiveness. Witness the attacks on Senator Edmund Muskie in 1971 and 1972. Each candidacy triggers a hundred side shows, a welter of endless and draining detail. The candidate is plunged into a morass of essentially incomprehensible regulations (state by state, to say nothing of Uncle Sam) and of dervish-like activity quite beyond his control, to say nothing of his sanity. In the past, presidential primaries have not reflected a banker's ideal of the way money should be handled, or a civics teacher's notion of electoral virtue. They have placed a superhuman burden on the simple physical energy of the candidates and their campaign staffs. The highest priority is given to symbolism and image - not substance.

The system itself defies common sense. How does any one contender compete in elections in 30 states and hundreds of district elections and caucuses for convention delegates? In the Democratic primaries, for example, a candidate is entered automatically in 14 state primaries. And it is worth noting that under this bizarre system we enjoy and demand, America has never elected a President who has been forced to compete actively in more than half a dozen primaries. Of course, that could change.

How much worse when, in 1971 and 1972, a sitting Republican President, Mr. Nixon, saw fit to inject himself into the Democratic primaries. With calculated trickery, he and his "men" turned the Democratic candidates - already strong competitors - into howling enemies. As campaign manager for Senator Muskie, I saw it firsthand. I saw our campaign-planning documents disappear. I saw their contents turn up in newspaper columns. Spies were planted by the Republicans in our campaign organization. My own law office was broken into and my files ransacked. Confidential documents relating to the Muskie campaign were discovered disassembled on a Xerox machine in our campaign office. Within the organization, days were consumed in trying to track down spies. The campaign was constantly disrupted. Our fund raisers were put on the White House "enemies list." Two of our closest campaign advisers - those who had worked for Henry Kissinger - were wiretapped.

It was frightening for me, as I prepared to testify before the Senate Watergate Committee, to be handed documents showing the involvement of the President of the United States, of the Attorney General, and of other high officers conspiring to destroy the candidacy of a man whom I considered great at the time and equally great today. It was shocking to read a memo written to Attorney General Mitchell and to Bob Haldeman, the chief of staff of the White House, in 1972 as follows:

Our primary objective, to prevent Senator Muskie from sweeping the early primaries, locking up the convention in April and uniting the Democratic Party behind him for the fall, has been achieved. The likelihood - great three months ago - that the Democratic Convention would become a dignified coronation ceremony for a centrist candidate who could lead a united party into the election is now remote.

What do we draw from this experience? I would hope we would all take a second look or a third look or a fourth look at the promises candidates make in primaries. I would hope we would be suspicious of whatever party is in power, Republican or Democratic, and its possible meddling in the other party's primaries. And if it is not too sacrilegious, I think we'd better take another look at the unintended and potentially undesirable results of well-meaning reform. First, we should keep asking, is the Campaign Reform Act of 1974 doing what needs to be done? Are such delegate election reforms within the Democratic Party producing the best candidates, and is the Republican Party doing what it should to assure fuller participation by the broadest segments of its adherents?

Perhaps nothing can be done about the election of 1976, except to endure. One can only hope that we are capable of learning from our mistakes, including hyperactivity in reform. There are certainly too many primaries. A simplistic answer of having a single national primary will not suffice. Perhaps regional primaries would help. Making shorter the pre-convention period during which the primaries can occur strikes me as desirable. Yet, I sometimes wonder, with a twinge of nostalgia, whether it was really so terrible to afford public officials and party leaders a superior chance to screen, even select, candidates in a convention to the end that the party may choose a person who, as Adlai Stevenson once observed, can "talk sense to the American people."

Berl Bernhard, a Washington attorney and a Dartmouth Trustee,was campaign manager for Senator Muskie in 1972. This essayfirst appeared in the Class of 1951 25-year book, edited byWoody Klein.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

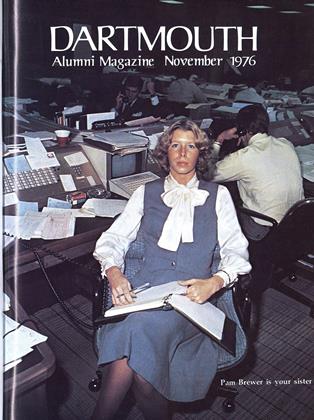

FeatureJUST LIKE THE REST OF US

November 1976 By A. KELLEY FEAD -

Feature

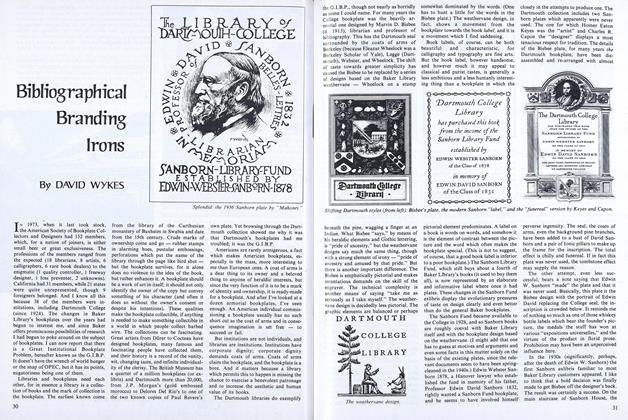

FeatureBibliographical Branding Irons

November 1976 By DAVID WYKES -

Feature

FeatureThe and the

November 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Feature

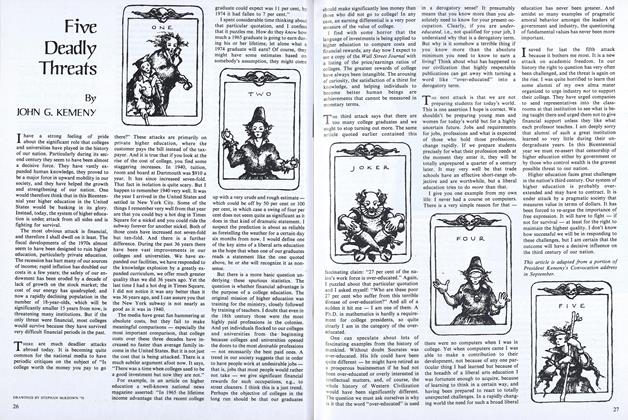

FeatureFive Deadly Threats

November 1976 By John G. Kemeny -

Article

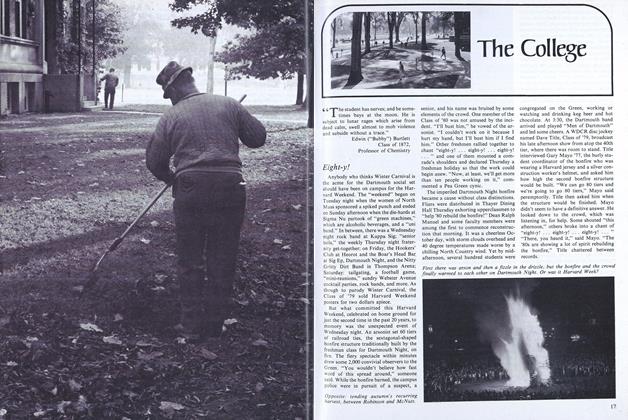

ArticleEight-y!

November 1976 -

Article

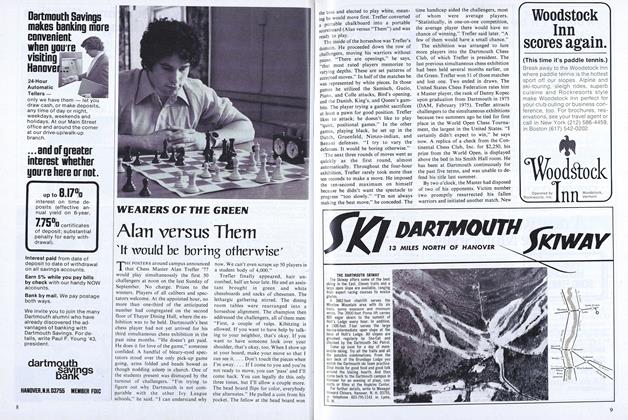

ArticleAlan versus Them 'It would be boring otherwise'

November 1976 By PIERRE KIRCH'78