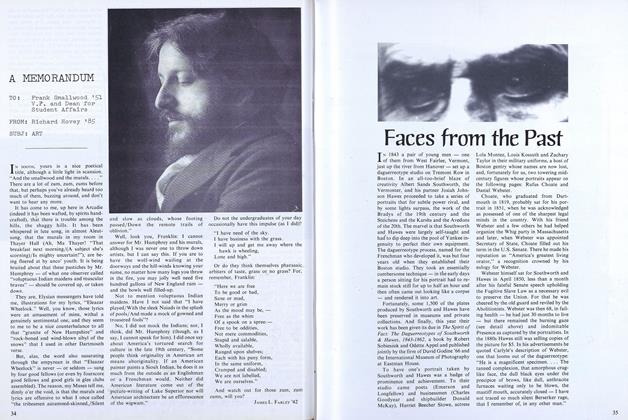

IN 1843 a pair of young men - one of them from West Fairlee, Vermont, just up the river from Hanover - set up a daguerreotype studio on Tremont Row in Boston. In an all-too-brief blaze of creativity Albert Sands Southworth, the Vermonter, and his partner Josiah Johnson Hawes proceeded to take a series of portraits that for subtle power rival, and by some lights surpass, the work of the Bradys of the 19th century and the Steichens and the Karshs and the Avedons of the 20th. The marvel is that Southworth and Hawes were largely self-taught and had to dip deep into the pool of Yankee ingenuity to perfect their own equipment. The daguerreotype process, named for the Frenchman who developed it, was but four years old when they established their Boston studio. They took an essentially cumbersome technique - in the early days a person sitting for his portrait had to remain stock still for up to half an hour and then often came out looking like a corpse - and rendered it into art.

Fortunately, some 1,500 of the plates produced by Southworth and Hawes have been preserved in museums and private collections. And finally, this year their work has been given its due in The Spirit ofFact: The Daguerreotypes of Southworth& Hawes, 1843-1862, a book by Robert Sobieszek and Odette Appel and published jointly by the firm of David Godine '66 and the International Museum of Photography at Eastman House.

To have one's portrait taken by Southworth and Hawes was a badge of prominence and achievement. To their studio came poets (Emerson and Longfellow) and businessmen (Charles Goodyear and shipbuilder Donald McKay), Harriet Beecher Stowe, actress Lola Montez, Louis Kossuth and Zachary Taylor in their military uniforms, a host of Boston gentry whose names are now lost, and, fortunately for us, two towering midcentury figures whose portraits appear on the following pages: Rufus Choate and Daniel Webster.

Choate, who graduated from Dartmouth in 1819, probably sat for his portrait in 1851, when he was acknowledged as possessed of one of the sharpest legal minds in the country. With his friend Webster and a few others he had helped organize the Whig party in Massachusetts and later, when Webster was appointed Secretary of State, Choate filled out his term in the U.S. Senate. There he made his reputation as "America's greatest living orator," a recognition crowned by his eulogy for Webster.

Webster himself sat for Southworth and Hawes in April 1850, less than a month after his fateful Senate speech upholding the Fugitive Slave Law as a necessary evil to preserve the Union. For that he was cheered by the old guard and reviled by the Abolitionists. Webster was then 68, in failing health - he had just 30 months to live - but there remained the burning gaze (see detail above) and indomitable Presence as captured by the portraitists. In the 1880s Hawes still was selling copies of the picture for $5. In his advertisements he quoted Carlyle's description of Webster, one that looms out of the daguerreotype: "He is a magnificent specimen. . . . The tanned complexion, that amorphous crag-like face, the dull black eyes under the precipice of brows, like dull, anthracite furnaces waiting only to be blown, the mastiff mouth, accurately closed - I have not traced so much silent Berserker rage, that I remember of, in any other man."

Features

-

Feature

FeatureBronx County Chairman

APRIL 1968 -

Feature

FeatureHENRY’S SPIEL

December 1990 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTHE SPIRIT OF ADVENTURE

Jan/Feb 2013 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySENIOR CANE

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Cover Story

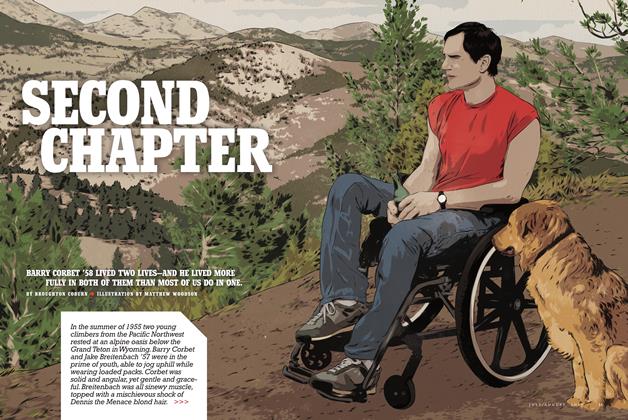

Cover StorySECOND CHAPTER

July/Aug 2013 By BROUGHTON COBURN -

Cover Story

Cover StoryOn Mount Washington, where the Geum Peckii blooms and blows

APRIL 1982 By Peter Heller