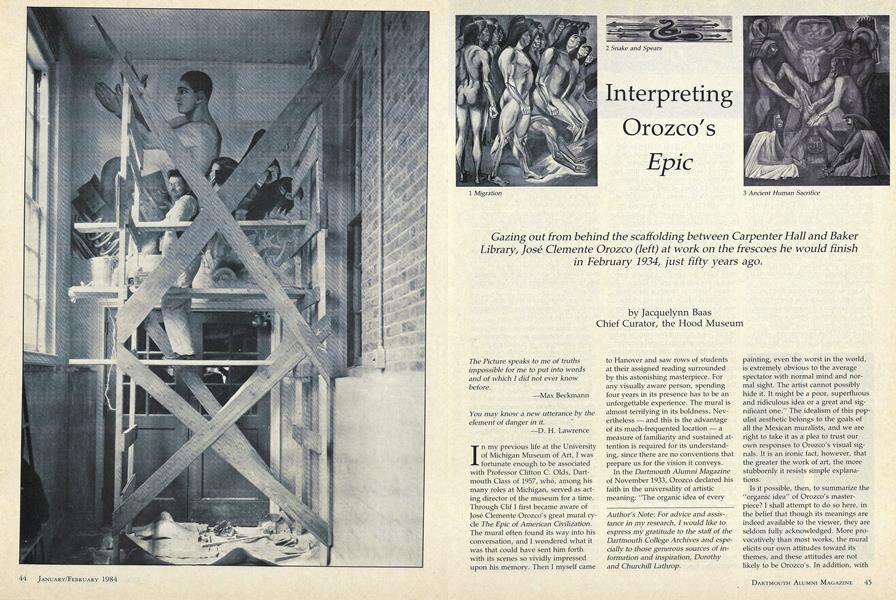

Gazing out from behind the scaffolding between Carpenter Hall and BakerLibrary, Jose Clemente Orozco (left) at work on the frescoes he would finishin February 1934, just fifty years ago.

Chief Curator, the Hood Museum

The Picture speaks to me of truthsimpossible for me to put into wordsand of which I did not ever knowbefore.

Max Beckmann

You may know a new utterance by theelement of danger in it.

D. H. Lawrence

In my previous life at the University of Michigan Museum of Art, I was fortunate enough to be associated with Professor Clifton C. Olds, Dartmouth Class of 1957, who, among his many roles at Michigan, served as acting director of the museum for a time. Through Clif I first became aware of Jose Clemente Orozco's great mural cycle The Epic of American Civilization. The mural often found its way into his conversation, and I wondered what it was that could have sent him forth with its scenes so vividly impressed upon his memory. Then I myself came to Hanover and saw rows of students at their assigned reading surrounded by this astonishing masterpiece. For any visually aware person, spending four years in its presence has to be an unforgettable experience. The mural is almost terrifying in its boldness. Nevertheless - and this is the advantage of its much-frequented location a measure of familiarity and sustained attention is required for its understanding, since there are no conventions that prepare us for the vision it conveys. In the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine of November 1933, Orozco declared his faith in the universality of artistic meaning: "The organic idea of every painting, even the worst in the world, is extremely obvious to the average spectator with normal mind and normal sight. The artist cannot possibly hide it. It might be a poor, superfluous and ridiculous idea or a great and significant one." The idealism of this populist aesthetic belongs to the goals of all the Mexican muralists, and we are right to take it as a plea to trust our own responses to Orozco's visual signals. It is an ironic fact, however, that the greater the work of art, the more stubbornly it resists simple explanations.

Is it possible, then, to summarize the "organic idea" of Orozco's masterpiece? I shall attempt to do so here, in the belief that though its meanings are indeed available to the viewer, they are seldom fully acknowledged. More provocatively than most works, the mural elicits our own attitudes toward its themes, and these attitudes are not likely to be Orozco's. In addition, with a work as historically-grounded as TheEpic of American Civilization, some knowledge of the circumstances under which it was created can direct our attention in useful ways. A thorough scholarly analysis would require careful study of the hundreds of preliminary working drawings Orozco made for the frescoes. I hope this can be accomplished in the near future. In the meantime, in recognition of the fiftieth anniversary of the completion of Orozco's Epic at Dartmouth College on February 13, 1934, I shall propose some interpretive guidelines that are intended to dispel lingering confusions about its essential message.

A key to understanding The Epic ofAmerican Civilization is an awareness of both Orozco's passionate idealism and his pessimism. Spain's greatest filmmaker, the late Luis Bunuel, declared that "Man is never free, yet he fights for what he can never be, and that is tragic." Orozco's sense of the human condition was based on the same conviction of tragic impasse. As many of his graphic works testify, his viewpoint was shaped by the experience of ten years of civil war that gripped Mexico from 1910 to 1920, at the outset of his career. Haunted by the savagery of this period, Orozco's humanist idealism took a resolutely apolitical form. He saw the dogmas of political and religious salvation, like concepts of race and nationality, as idols corrupting understanding, preventing the emancipation of the human spirit. For Orozco, in sharp contrast to his fellow muralist Diego Rivera, history is merely a prelude to liberation. Only by throwing off the shackles of the creeds and prejudices that have enslaved mankind to authoritarian purposes can the real "New World" a genuine harmony of individual expression and social purpose - come into being. The American continent, where indigenous and migrating peoples have mingled for centuries, figured in Orozco's imagination as the symbolic stage for this ultimate triumph of the human spirit. And the walls of the reserve corridor in Baker Library struck him as a perfect location for his statement of this vision, which he conceived as The Epic of AmericanCivilization.

Orozco had been brought to Hanover by the Department of Art in the spring of 1932 to demonstrate his skill as a muralist. His first Dartmouth fresco, "Man Released from the Mechanistic" (on page 44), was executed in the corridor Jinking Baker Library and Carpenter Hall, home of the Art Department. Originally planned as the focal point of a mural cycle on the theme of Daedalus, the panel was, according to Orozco, "post-war" in theme. He commented that it "represents man emerging from a heap of destructive machinery symbolizing slavery, automatism, and the converting of a human being into a robot, without brain, heart, or free will, under the control of another machine. Man is now shown in command of his own hands and he is at last free to shape his own destiny." This clearly anticipates the themes of the mural cycle Orozco finally painted in the reserve room. Both "Man Released from the Mechanistic" and The Epic of AmericanCivilization envision the transformation of humanity from spiritual bondage to a new creative freedom, and both express this idea through Utopian visions of man's control over the machine, freeing him from enslavement to its destructive momentum.

In his prospectus for the mural, written in 1932, Orozco relates this Utopian impulse to his epic subject.

The American continental races are now becoming aware of their own personality, as it emerges from two cultural currents the indigenous and European. The great American myth of Quetzalcoatl is a living one embracing both elements and pointing clearly, by its prophetic nature, to the responsibility, shared equally by the two Americas, of creating here an authentic New World civilization. I feel that this subject has a special significance for an institution such as Dartmouth College which has its origin in a continental rather than in a local outlook the foundation of Dartmouth, I understand, predating the founding of the United States.

In accordance with this plan, Orozco took advantage of the division of the reserve reading room into east and west wings to portray America's "two cultural currents." The indigenous history of the Americas before Cortez is presented in the west wing; the European-influenced phase (Orozco himself was of Spanish descent) is presented in the east wing. Both parts of the mural cycle contain a prophetic figure: Quetzalcoatl in the west wing (panels 5-7), and a triumphant Christ in the east wing (panel 21). From Orozco's perspective of the shared prophecy of the two Americas, these figures are functional complements, aspects of a single promise.

As the mural developed, the horrors of the modern world loomed larger than the original vision of an "authentic new world civilization," which Orozco finally relegated to the section of the south wall facing the reserve desk. This shift was evidently influenced by the artist's only trip to Europe, during the summer of 1932 when he had barely begun the frescoes of the west wing. At this time, he encountered the despair left by World War One and the rising dictatorship that augured another world war. In his autobiography (published in English by the University of Texas Press in 1962), Orozco recalls stories in European newspapers, "documented beyond dispute, of the shameful politicians and the dealers in cannon fodder. Exposures of how Germany and the Al-lies had exchanged critical materials during the progress of the First World War and so prolonged that war in the interests of big speculators." He returned with a darker view of the likelihood of an imminent answer to the problems of mankind, and with a sharpened sense of a perennial pattern of dehumanization. This experience influnced the final form of his Epic. Traditionally, the epic hero founds a new civilization (a "city of destiny," like Virgil's Rome) in a mythic time that is continuous with known history. Orozco wrenched these conventions into an antithesis. His epic hero is tragically confined to the realm of mythic promise, while the founding of the historic city simply begins another cycle of human misery. Cortez (panel 13) is its militarized anti-hero.

The murals of the west wing form a coherent cycle around a single mythic moment in the ancient history of the Americas, a revelation of cultural fulfillment that was extinguished by greed, superstition, and aggression. Although Orozco based his cycle on the story of the Toltec priest-ruler Quetzalcoatl, he did not simply turn this material into a narrative. Rather, he adapted its archetypal features the bringer of civilization who is cast out by his own people and prophesies his return after a period of destruction to his own sense of the frustrated hopes of human history. Orozco was plain enough about this in his written commentary on his plan. "It is to be understood," he declared, "that there is no literary or other record of the exact implications of this ancient myth of Quetzalcoatl and that this interpretation grows out of the inspired idealism and creative imagination of Orozco." Our interpretation, then, must be guided by the artist's visual cues rather than by any particular version of Quetzalcoatl's protean identity, either as an historical figure or as a pre-Cortesian god.

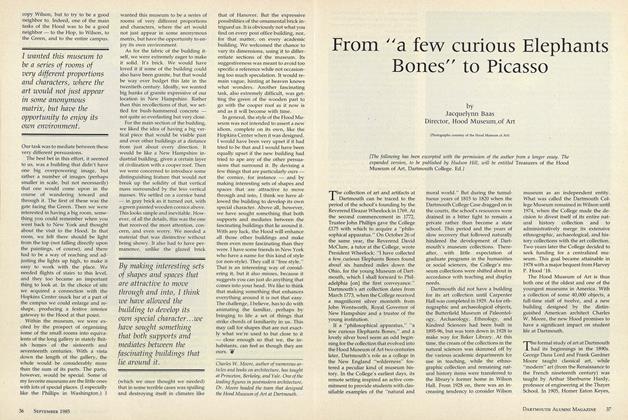

On the far west wall we see three representations of Aztec society: in the left panel, the migration of the Aztecs into central Mexico (panel 1); in the right panel, the ancient practice of human sacrifice that was eliminated under Quetzalcoatl and revived by the Aztecs (panel 3); and above the doorway, a symbolic statement of the ferocity of Aztec culture in the form of a rattlesnake flanked by spears (panel 2). In "Migration" the Aztecs are shown marching in lock-step phalanxes toward their destiny the conquest and absorption of indigenous cultures into a single warlike, fetishistic, and totalitarian society. We are alerted to the significance of the migration panel by the contrast drawn between its grimly militaristic figures (the fallen marcher dramatizes the price exacted) and the harmoniously varied culture suggested in the panels devoted to Quetzalcoatl's epiphany (panels 5 and 6).

"Ancient Human Sacrifice" takes up the right-hand side of the west wall. Orozco's emphasis is not on the Aztecs' sun-worship (Quetzalcoatl is to be the only light-bringer), but on their distortion of ancient fertility rituals into a dark, chthonic obsession with human sacrifice. The image that presides over this ritual can be identified on the basis of the closed eyes, strongly defined brow, flat nose, and slack, downturned mouth. It is the head of the malevolent goddess Coyolxauhqui, who was decapitated and dismembered by her half-brother Huitzilopochtli, militaristic patron god of the Aztecs. The priest who carries out the ritual is masked, as are the victim and other participants, emphasizing the blind impersonality of this sacrifice of human life to a dead god. The west panels thus introduce the theme of man's bondage to an abstract, mechanistic destructiveness which the European panels restate in even more monstrous terms.

On the long north wall of the west wing we are addressed by "The Coming of Quetzalcoatl" (panel 5), a contrasting vision of the Toltec priest-ruler whose name literally means "feathered serpent." The clear-eyed humanity of Quetzalcoatl breaks the spell of the primitive gods arrayed behind him. Orozco's expressive emphasis is on the classically balanced powers of eyes and hands. They signify knowing and doing, the true sources of human culture. Bringing the light of knowledge and peace, Quetzalcoatl awakens mankind from its barbaric dreams. He reveals the potential for brotherhood and in the panel depicting the "Golden Age" (panel 6) for creation. However, the human tendency towards mindless superstition and greed for power compels the beneficent hero-god to depart on his raft of serpents ("The Departure of Quetzalcoatl," panel 7). Leaving behind him a terrified band of enemies, Quetzalcoatl prophesies an era of unprecedented destruction and his eventual return.

The narrow overdoor panels on either end of the west wing's north wall were the first frescoes completed in the room. In "Aztec Warriors," the far lefthand panel (panel 4), stonelike faces emerge from eagle and jaguar costumes emblematic of the warrior class. The primary purpose of their systematized aggression was to supply sacrificial victims whose hearts and blood would feed the sun and thus ensure the well-being of the universe. The warriors are accompanied by a monumental sculptured head of a feathered serpent, an idolatrous perversion of the idea of Quetzalcoatl. The far righthand panel on this wall, "The Prophecy" (panel 8), depicts the coming of European civilization in the form of armor-masked soldiers bearing the Christian cross as a huge piked weapon. This image declares the militant nature of the god into which European culture transformed Christ and his teachings. Thus, on either side of scenes showing the appearance of Quetzalcoatl, his Golden Age and his departure, we are offered complementary glimpses of the organized brutality of a humanity alienated from what Orozco called the "Power of Good in the Universe."

The two narrow panels on either side of the east doorway of the west wing symbolize the idolatry of primitive religion in North America (panels 9-10). Here, totem poles are represented in caricatures of Northwest Coast bird images. Nothing better clarifies the artist's uncompromising humanism, which condemns primitive religion as absurd fetishism. Far from idealizing tribal societies, Orozco implies that they, too, contribute to man's authoritarian legacy.

The scenes of the east wing shift our attention from indigenous history and myth to their counterparts after the European conquest. The first panel of the long north wall, "Cortez and the Cross" (panel 13), depicts the triumph of the conquistador whose arrival heralded the mechanistic and exploitive impulses of European civilization. Cortez is portrayed with a curiously selfabsorbed tenderness amid the carnage. This stylistic dissonance parodies the conventions of the Spanish renaissance portraiture contemporary with Cortez. His El Greco-like serenity conveys an unwavering faith in the righteousness of his cause. The face of Cortez is so eerily out of key with the expressionist context of human suffering that it becomes another kind of mask.

In the next panel the gray steel of Cortez's armor is transformed into a monstrous, chaotic presence: towards the center of this wall, we are confronted with Orozco's expressionistic representation of "The Machine" (panel 14). Its gray and jagged mass appears to feed on the piled human bodies at the lower left, as though it were a demonic incarnation of the culture's anti-human materialism. The message, surely, is that the impersonal chaos of the modern era permits no more concern for human life than did the barbaric rituals of the Aztecs. The Machine, which symbolizes the mass regimentation of modern society for inhuman goals, is the controlling theme of this wing. Its presence is starkly emphasized in the two vertical panels on either side of the doorway (panels 11-12). Here we see fantasies of machines possessed by their own life modern equivalents of the totem-idols depicted in the west wing (panels 9-10).

The cultural manifestation of the machine civilization is the cold, repressive world of the schoolhouse and town meeting depicted in the "Anglo-America" (panel 15). Here Orozco fuses critiques of American Puritanism and of "organization man" anonymity, blending them into the life-denying gray that extends across the entire wall. This vision of repression is complemented by the violent scenario of "Hispano-America," exploding in revolution and all but destroyed by imperialistic exploitation (panel 16).

At the end of this long northern wall is the unforgettable imagery of "Gods of the Modern World" (panel 17). Here academicians, supposedly the guardians of the accumulated knowledge of humankind, are depicted as living corpses presiding over the routine stillbirth of useless knowledge. Behind them, the world goes up in flames, just as in the Cortez panel at the opposite end of the wall. To the right, on the east wall, is Orozco's outraged portrayal of modern warfare as "Modern Human Sacrifice" (panel 18), corresponding to "Ancient Human Sacrifice" on the far west wall opposite (panel 3). The body of an unknown soldier, his skeletal hands still testifying to his final agony, is buried beneath the trappings of patriotism: colorful flags, wreaths, monuments, speeches, brass bands, and the "eternal flame" that marks the grave of the decorously anonymous victim of modern nationalism. The overdoor panel to the left, showing a junk pile of three historical eras of totemistic animal symbols of warfare and empire, suggests the continuity between primitive and modern chauvinism (panel 19).

"The Modern Migration of the Spirit," on the right side of the east wall, is the climax of the mural (panel 21). Significantly, at an early planning stage Orozco referred to this scene as "The End of Superstition Triumph of Freedom." Here the human spirit is dramatized as a Christ-figure rejecting the appointed destiny of crucifixion. He has chopped down his cross and destroyed the causes of his agony: militarism (represented by tanks and armaments), religion (the cross and the Buddha image), and the authoritarian perversion of culture (a fallen lonic column and the fragment of an Aphrodite). Bearing the wounds of his oppression, his spiritual purification symbolized by the flame-like colors of his body, man has finally cast off his chains that are symbolically associated with death in the overdoor panel to the right (panel 20).

Orozco thus portrays mankind as ultimately triumphant. Appropriately, the face of this figure is that of a Christ Pantocrator, the Byzantine image of the triumphant, fearsome Christ of the Second Coming. In effect, this figure is the ultimate fulfillment of the prophecy of Quetzalcoatl (panel 7). For the pose, Orozco refers to a classical humanist model. Carlos Sanchez '23, who was artist in residence at Dartmouth when the mural was painted, has noted that the compositional prototype is Leonardo's famous drawing of the Vitruvian man. Sanchez also recalled that Orozco borrowed the components of Quetzalcoatl from the face of God the Father on Michelangelo's Sistine Ceiling. The Promethean individualism of the High Renaissance was an inexhausible source of inspiration for Orozco. However, its atmosphere of cosmic order has been transformed into a blazing dreamworld of torment, outrage, and prophetic exclamation. For Orozco, order can only be generated from within, as a moral statement, not from without, as a reflection of existing structures.

The panels across from the reserve desk, in the center of the south wall, have traditionally been titled "Modern Industrial Man." However, their Utopian import is better conveyed by an earlier title: "The Dream of an Ideal Culure of the Future." Here the Machine has been diverted from the exercise of power for its own sake to the service of man, while industrial man himself is shown planning and working cooperatively (panels 22 and 24). This vision of the future recalls Quetzalcoatl's preColumbian vision of the Golden Age (panel 6). In the central panel over the bookshelves, the worker of the future is free to put down his tools and nourish his spirit (panel 23). The new architecture depicted in these panels Signifies a harmony of function and beauty that is no longer dependent on cultural ornament. These last five panels, serve, in effect, as a coda, balancing the lost utopia of Quetzalcoatl with a contemporary vision of human possibility.

From the perspective granted us by an intervening half-century, what is most striking about The Epic of American Civilization is Orozco's refusal to settle for easy solutions. He does not idealize any moment of the historical past, nor the historical process itself, nor does he pit indigenous American civilizations against those of Europe. Moreover, despite the anarchist overtones of his vision of triumph, Orozco shows no trust in any specific political solution. His visual epic of the Americas is inspired by sheer indignation at the continuing degradation of the human spirit, in patterns that are hauntingly similar in ancient and modern societies. Understandably, Orozco's faith in a nobler human destiny is most powerfully conveyed by his insistence on the full measure of human destructiveness. Yet the creative potential of mankind is also celebrated, as a messianic hope that must be re-imagined perpetually into the future. Walter Benjamin, acknowledging the ruins of Utopian aspiration in Europe in the 1920s, expressed the paradox inherent in this persistent claim of the ideal: "Only because of the hopeless is hope given to us." One must not lie about the failures of history. Orozco's Epic ofAmerican Civilization is its compassionate witness, re-enacting the chronicles of human suffering within a vision of invincible promise.

1 Migration

2 Snake and Spears

3 Ancient Human Sacrifice

4 Aztec Warriors a The Coming of Quetzalcdatl 6 The Pre-Columbian Golden Age 7 The Departure of QueUalcoat! 8 The Prophehecy

9 & 10 Totem Poles

9 & 10 Totem Poles

13 Cortex, and the Cross 14 The Machine 15 Anglo-America 16 Hispano-America 17 Gods of the Modern World

11 & 12 Machine Images

11 & 12 Machine Images

18 Modern Human Sacrifice

19 Symbols of Nationalism

20 Chains of the Spirit

21 Modern Migration of the Spirit

22 Ideal Modern Culture I

23 Ideal Modern Culture II

24 Ideal Modern Culture III

Author's Note: For advice and assistance in my researchl would like toexpress my gratitude to the staff, of theDartmouth College Archives and especially to those generous sources of information and inspiration, Dorothyand Churchill Lathrop.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

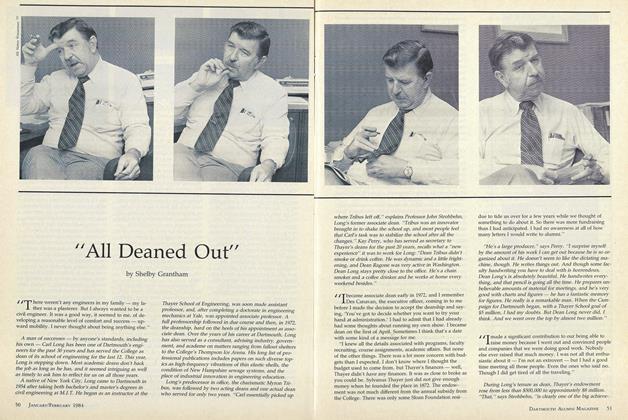

Feature"All Deaned Out"

January | February 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Peripatetic "Silver Fox"

January | February 1984 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe Outing Club at 75

January | February 1984 By Willem Lange -

Cover Story

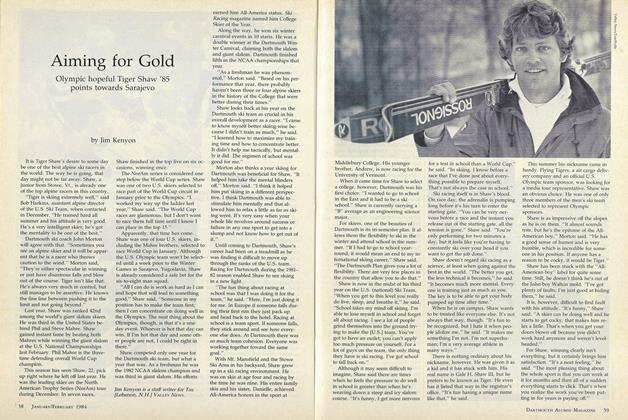

Cover StoryAiming for Gold

January | February 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Article

ArticleModern politics "up close"

January | February 1984 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1956

January | February 1984 By Clement B. Malm

Jacquelynn Baas

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThird Century Fund Final Report

DECEMBER 1971 -

Feature

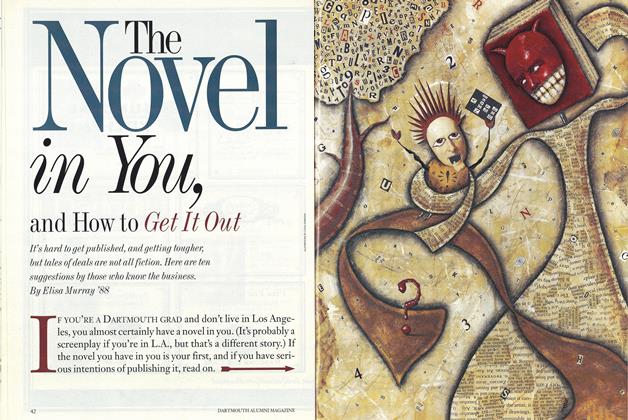

FeatureThe Novel in You, and How to Get It Out

DECEMBER 1996 By Elisa Murray '88 -

Cover Story

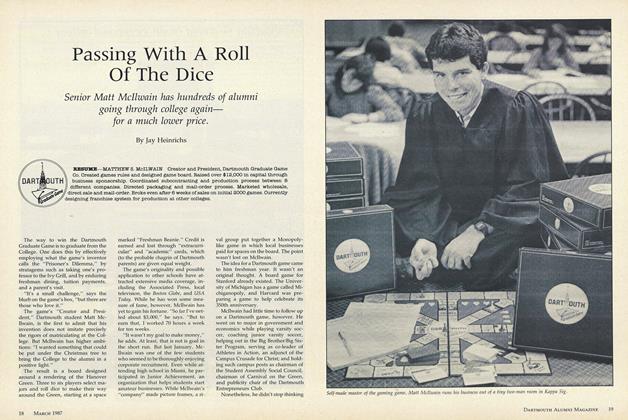

Cover StoryPassing With A Roll Of The Dice

MARCH • 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeaturePromise Kept

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 By KEVIN NANCE -

Feature

FeatureThe Uncompetitive Society

MAY • 1987 By Richard D. Lamm -

Feature

FeaturePursuits

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 By ZOEY SLESS-KITAIN