Ordinarily, a gentleman who suggests to his associates that the problem facing their profession is an overabundance of business would be regarded with suspicion.

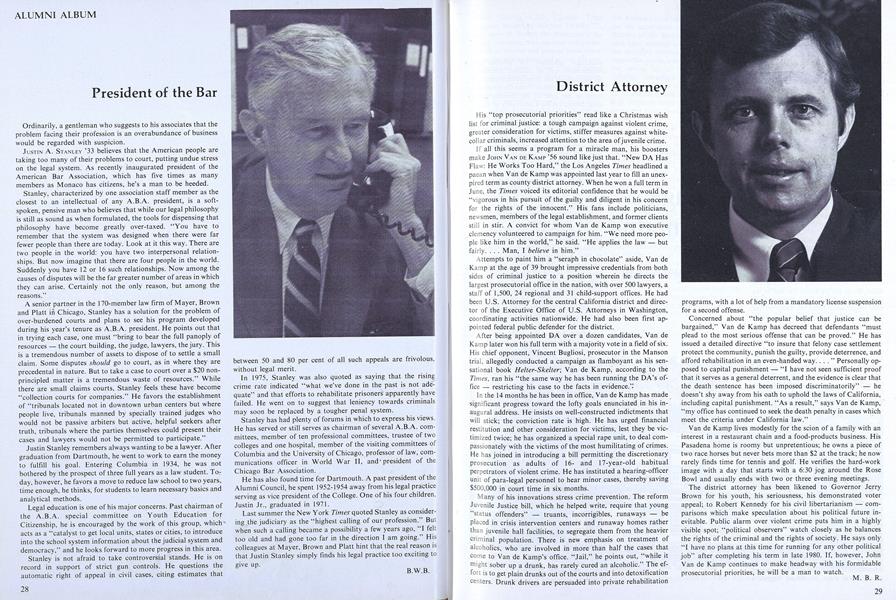

JUSTIN A. STANLEY '33 believes that the American people are taking too many of their problems to court, putting undue stress on the legal system. As recently inaugurated president of the American Bar Association, which has five times as many members as Monaco has citizens, he's a man to be heeded.

Stanley, characterized by one association staff member as the closest to an intellectual of any A.B.A. president, is a softspoken, pensive man who believes that while our legal philosophy is still as sound as when formulated, the tools for dispensing that philosophy have become greatly over-taxed. "You have to remember that the system was designed when there were far fewer people than there are today. Look at it this way. There are two people in the world: you have two interpersonal relationships. But now imagine that there are four people in the world. Suddenly you have 12 or 16 such relationships. Now among the causes of disputes will be the far greater number of areas in which they can arise. Certainly not the only reason, but among the reasons."

A senior partner in the 170-member law firm of Mayer, Brown and Piatt in Chicago, Stanley has a solution for the problem of over-burdened courts and plans to see his program developed during his year's tenure as A.B.A. president. He points out that in trying each case, one must "bring to bear the full panoply of resources - the court building, the judge, lawyers, the jury. This is a tremendous number of assets to dispose of to settle a small claim. Some disputes should go to court, as in where they are precedental in nature. But to take a case to court over a $20 nonprincipled matter is a tremendous waste of resources." While there are small claims courts, Stanley feels these have become "collection courts for companies." He favors the establishment of "tribunals located not in downtown urban centers but where people live, tribunals manned by specially trained judges who would not be passive arbiters but active, helpful seekers after truth, tribunals where the parties themselves could present their cases and lawyers would not be permitted to participate."

Justin Stanley remembers always wanting to be a lawyer. After graduation from Dartmouth, he went to work to earn the money to fulfill his goal. Entering Columbia in 1934, he was not bothered by the prospect of three full years as a law student. Today, however, he favors a move to reduce law school to two years, time enough, he thinks, for students to learn necessary basics and analytical methods.

Legal education is one of his major concerns. Past chairman of the A.B.A. special committee on Youth Education for Citizenship, he is encouraged by the work of this group, which acts as a "catalyst to get local units, states or cities, to introduce into the school system information about the judicial system and democracy," and he looks forward to more progress in this area.

Stanley is not afraid to take controversial stands. He is on record in support of strict gun controls. He questions the automatic right of appeal in civil cases, citing estimates that between 50 and 80 per cent of all such appeals are frivolous, without legal merit.

In 1975, Stanley was also quoted as saying that the rising crime rate indicated "what we've done in the past is not adequate" and that efforts to rehabilitate prisoners apparently have failed. He went on to suggest that leniency towards criminals may soon be replaced by a tougher penal system.

Stanley has had plenty of forums in which to express his views. He has served or still serves as chairman of several A.B.A. committees, member of ten professional committees, trustee of two colleges and one hospital, member of the visiting committees of Columbia and the University of Chicago, professor of law, communications officer in World War II, and'president of the Chicago Bar Association.

He has also found time for Dartmouth. A past president of the Alumni Council, he spent 1952-1954 away from his legal practice serving as vice president of the College. One of his four children, Justin Jr., graduated in 1971.

Last summer the New York Times quoted Stanley as considering the judiciary as the "highest calling of our profession." But when such a calling became a possibility a few years ago, "I felt too old and had gone too far in the direction I am going." His colleagues at Mayer, Brown and Piatt hint that the real reason is that Justin Stanley simply finds his legal practice too exciting to give up.