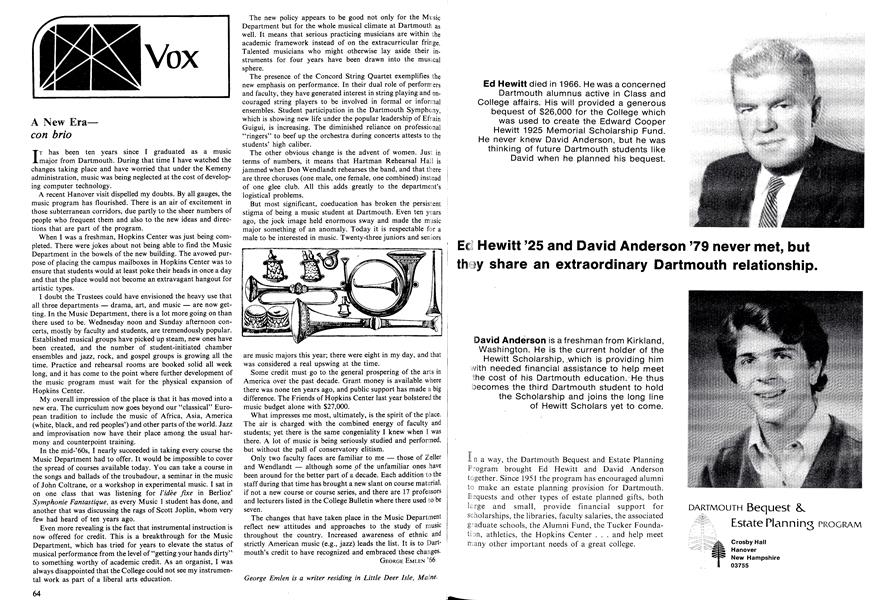

IT has been ten years since I graduated as a music major from Dartmouth. During that time I have watched the changes taking place and have worried that under the Kemeny administration, music was being neglected at the cost of developing computer technology.

A recent Hanover visit dispelled my doubts. By all gauges, the music program has flourished. There is an air of excitement in those subterranean corridors, due partly to the sheer numbers of people who frequent them and also to the new ideas and directions that are part of the program.

When I was a freshman, Hopkins Center was just being completed. There were jokes about not being able to find the Music Department in the bowels of the new building. The avowed purpose of placing the campus mailboxes in Hopkins Center was to ensure that students would at least poke their heads in once a day and that the place would not become an extravagant hangout for artistic types.

I doubt the Trustees could have envisioned the heavy use that all three departments - drama, art, and music - are now getting. In the Music Department, there is a lot more going on than there used to be. Wednesday noon and Sunday afternoon concerts, mostly by faculty and students, are tremendously popular. Established musical groups have picked up steam, new ones have been created, and the number of student-initiated chamber ensembles and jazz, rock, and gospel groups is growing all the time. Practice and rehearsal rooms are booked solid all week long, and it has come to the point where further development of the music program must wait for the physical expansion of Hopkins Center.

My overall impression of the place is that it has moved into a new era. The curriculum now goes beyond our "classical" European tradition to include the music of Africa, Asia, America (white, black, and red peoples') and other parts of the world. Jazz and improvisation now have their place among the usual harmony and counterpoint training.

In the mid-'60s, I nearly succeeded in taking every course the Music Department had to offer. It would be impossible to cover the spread of courses available today. You can take a course in the songs and ballads of the troubadour, a seminar in the music of John Coltrane, or a workshop in experimental music. I sat in on one class that was listening for l'idée fixe in Berlioz' Symphonie Fantastique, as every Music 1 student has done, and another that was discussing the rags of Scott Joplin, whom very few had heard of ten years ago.

Even more revealing is the fact that instrumental instruction is now offered for credit. This is a breakthrough for the Music Department, which has tried for years to elevate the status of musical performance from the level of "getting your hands dirty" to something worthy of academic credit. As an organist, I was always disappointed that the College could not see my instrumental work as part of a liberal arts education.

The new policy appears to be good not only for the Music Department but for the whole musical climate at Dartmouth as well. It means that serious practicing musicians are within the academic framework instead of on the extracurricular fringe. Talented musicians who might otherwise lay aside their instruments for four years have been drawn into the musical sphere.

The presence of the Concord String Quartet exemplifies the new emphasis on performance. In their dual role of performers and faculty, they have generated interest in string playing and encouraged string players to be involved in formal or informal ensembles. Student participation in the Dartmouth Symphony, which is showing new life under the popular leadership of Efrain Guigui, is increasing. The diminished reliance on professional "ringers" to beef up the orchestra during concerts attests to the students' high caliber.

The other obvious change is the advent of women. Just in terms of numbers, it means that Hartman Rehearsal Hall is jammed when Don Wendlandt rehearses the band, and that there are three choruses (one male, one female, one combined) instead of one glee club. All this adds greatly to the department's logistical problems.

But most significant, coeducation has broken the persistent stigma of being a music student at Dartmouth. Even ten years ago, the jock image held enormous sway and made the music major something of an anomaly. Today it is respectable for a male to be interested in music. Twenty-three juniors and seniors are music majors this year; there were eight in my day, and that was considered a real upswing at the time.

Some credit must go to the general prospering of the arts in America over the past decade. Grant money is available where there was none ten years ago, and public support has made a big difference. The Friends of Hopkins Center last year bolstered the music budget alone with $27,000.

What impresses me most, ultimately, is the spirit of the place. The air is charged with the combined energy of faculty and students; yet there is the same congeniality I knew when I was there. A lot of music is being seriously studied and performed, but without the pall of conservatory elitism.

Only two faculty faces are familiar to me - those of Zeller and Wendlandt - although some of the unfamiliar ones have been around for the better part of a decade. Each addition to the staff during that time has brought a new slant on course material, if not a new course or course series, and there are 17 professors and lecturers listed in the College Bulletin where there used to be seven.

The changes that have taken place in the Music Department reflect new attitudes and approaches to the study of music throughout the country. Increased awareness of ethnic and strictly American music (e.g., jazz) leads the list. It is to Dartmouth's credit to have recognized and embraced these changes.

George Emlen is a writer residing in Little Deer Isle, Maine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePursuing Sleep

February 1976 By B.K. THORNE, NANCY DECATO -

Feature

Feature'Save the zebra! Save the zebra!'

February 1976 By GREGORY SCHWARZ -

Feature

Feature'... A whole pool of frustration, anger, resentment...'

February 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Feature

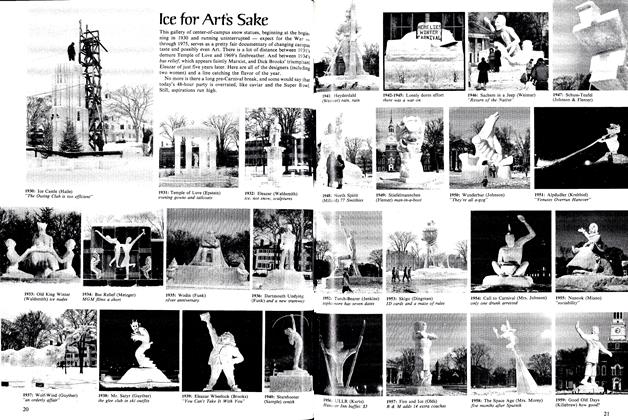

FeatureIce for Arťs Sake

February 1976 -

Article

ArticleWinter Games

February 1976 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

February 1976 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE