Though he is undoubtedly unaware of it and certainly never uses it. Dr. Peter Hauri has a native gift that makes it pleasuresome to associate with him and must be an asset in his treating the ragged and tender feelings of insomniacs: people look at him and instantly like him.Almost every bit of his conversation,outside his family, is about his subject:researching sleep problems andproviding treatment for insomnia.But his personality makes everyonemeeting him wonder about hisprobably large feeling for humanitybeyond the sleep-starved. Any hintabout such philosophical wondermentquickly brings the topic backto sleep, however. His academicdegrees, including a doctorate inclinical psychology, reflect concentrationin sleep research, which hasbeen his professional life for almost15 years. There are few sleepresearchers anywhere, with no morethan 20 sleep clinics across thewhole country.

Hauri smiles often, always speaksaffably, moves with a tall jauntiness,has the air of the outdoors. Quitefrequently he skis from his home atthe northern base of Balch Hill tothe sleep clinic. People guess that hecame from Switzerland before hebecame an American. They're right.

TREPIDATION? NO. The word had entered my mind, but it didn't really apply now because I knew I had nothing to lose. Anxiety? Yes. Not about the upcoming experience, because what could I lose except a few days' time and not too much money? So, what was on my mind mainly? Hope, I guess. Yes, hope for sure. Insomnia had been a plague, a burden, an anchor, a disrupter, a weakener, and I was in every way anxious to take advantage of what Dr. Peter Hauri was providing in his sleep clinic at the Dartmouth Medical School.

HAURI: Some apprehension on thepart of the patient is natural andcan be expected. However, itsprevalence does not conflict with thepatient's sleep clinic session, for insomniacsare often in an upset stateand we must study them as they are.

It's been a long time since Hanover of the '50s, but at least I remembered that the medical buildings were at the north end of the campus. The general area there has changed in the past few decades, but I had no trouble finding the entrance to the Medical School itself. As I rode the large and fast elevator to the seventh floor, I wondered if I had a preconceived idea about what a sleep clinic might be like. I found I didn't really and it was just as well. The entrance to the sleep clinic is a doorway marked 703 and it's entirely like all the other doors along both sides of the lengthy corridor in the Remsen Building. A step inside, however, showed that it was no ordinary array of small offices or laboratories. There was a trio of tiny bedrooms, one of which I was to occupy, more or less, for the next three nights and days. Each little room had a comfortable bed, thick carpeting, modern office-type furniture, and a modern painting on the wall. Overall, the immediate feeling was pretty much of cheerful smallness. The rest of the sleep lab, with facilities on both sides of the corridor, included Dr. Hauri's private office, the office of his assisting technicians, and several rooms with technical equipment.

HAURI: Our facilities are limited forfinancial reasons. We wish theycould be much better, and perhapsthey will be sometime.

At this point I should say what, specifically, brought me to Hanover. I had complained over the years to my own family doctor about my insomnia, and when he learned about Dr. Hauri's sleep clinic he contacted him and asked specifically about sending me to the clinic for treatment. I received a very long personality questionnaire to fill out - actually, filling it out took a couple of hours - and then I was notified that I seemed to be a suitable sleep clinic patient.

HAURI: We have heavily detailed thequestionnaire, and insomniacsdetermined to get help fill it outcompletely and submit it to us. Itturns off about one third of theoriginal applicants, we regret.

The clinic applicants' problemsfall into three large categories: thosewith medical problems such asarthritis and the pains that can preventsleep; the people with psychologicalproblems like depressionand anxiety. They make up about athird of those applying and in theircases we recommend the help of psychiatry.The third category I callprimary insomniacs: men andwomen with non-medical and non-psychologicalsleep problems thatwe consider treatable. More womenthan men come to the clinic. Menseem much more reluctant to admitthe sleep problem.

It's repetitive, but it must bestressed that patients come to theclinic only after the recommendationof a physician. Yes, it's a kindof filtering process, one that'snecessary. I get many calls frompeople who haven't been to theirphysicians.

It was now shortly after 9 p.m., and I was assigned a room, unpacked my small bag, and got into pajamas. The technical part of the session began almost immediately. It took a little while, but a number of electrodes were attached to my head and my legs. When I got into bed all the electrode wires were attached to a junction box, and the technician explained that that linked the electrodes to a polygraph machine, which recorded on paper the various doings of my mind and body essential for sleep analysis.

HAURI: The fee for the whole sleepclinic session is $300 per patient, thecheapest sleep clinic fee there is. Atother clinics, it is $700 or $800. BlueCross/Blue Shield pays part of it.

With 15 electrode wires in place on me, those familiar words - trepidation, anxiety, etc. - started to go through my mind again. An insomniac to begin with, how could I possibly sleep in a nest of wires? I learned in a hurry that it wasn't very bothersome. Once in bed, with my head on the pillow, I practically forgot about the wires, and later Dr. Hauri told me that just about every patient soon does. They did not interfere with what little sleep I got. So even though I knew I looked like some kind of Medusa, the physical aspect of participating in the sleep clinic course turned out to be a very minor thing.

HAURI: The electrodes - and asensor, called a thermistor, placednear the nose to record breathtemperature - are to record brainwaves, breathing rate, legmovements, and heart action.

What was that first night's sleep really like? The answer is that it was pretty bad. I had been told that I would be more or less able to simulate sleeping in my own bed at home, but I hadn't been smart enough to realize the latitude that gave me. I turned the light off near the bed promptly at 10 p.m., thinking that was the proper thing to do. That was the first mistake. I didn't have to. At home I never go to sleep without reading a while first. I should have brought something to read with me, or I should have perhaps asked the assistant in the lab for something to read. I didn't. I lay there. I tried to concentrate on getting to sleep. That didn't work, as usual, for a long time.

There was a second thing bothering me. In addition to reading before sleeping, I invariably have a snack. In fact, you could very well say that two, three, or four hours after dinner I have a supper. I hadn't realized that I could have done something about that. I could have brought something in the room with me. But I hadn't. And I wasn't smart enough to ask the assistant if there was anything in a refrigerator that I might have. So that first night was fairly miserable - partly because I didn't realize I could have done something about it. I was feeling pretty rocky when I woke up in the morning. And I certainly doubted that I'd actually slept more than a few hours.

My first full day in Hanover, I was pretty much on my own. I did some walking, visiting the Inn, looking over the new buildings in the vicinity of Tuck, and up toward Bartlett Tower. Because of the way I hadn't slept the previous night I wasn't very spry, but overall it was a very enjoyable day in Hanover aside from that, and I should have taken full advantage of it.

At about 9:30 on my second night, the electrodes were attached to me as they had been the night before and I got into bed. Now I would use the word "trepidation" because I felt that somewhat acclimated to the sleep clinic, and having met and talked with affable Dr. Hauri, I - well, I almost felt it would be incumbent upon me to have as good a night's sleep as possible. It worked out fairly well. I did get into bed promptly at 10 p.m. and then I did not put out the light. I had bought several books and magazines in the stores on Main Street, and I made up my mind, with the consent of Hauri, that I would simply read until I felt drowsy. I did read for a half hour, and then I remembered that it was just about my usual time for late supper. And then I was very glad that during the day I had had some foresight. From Lou's I had taken out two very large sandwiches and a large milk shake. I had one of the sandwiches and the milk shake, read some more, and then put out the light.

HAURI: Some patients wouldn'tconsider eating at night. Others havesmall feasts for themselves. It's upto them. They often get up duringthe night, as they would at home,and it is no problem at all.

I guess I would like to say now that with the comfortable surroundings, my appetite for reading and supper taken care of, I got right to sleep. I didn't quite do that, but it was different from the night before.

I'm pretty sure the eating was a good idea, but I'm not sure about the big milkshake. Before long I woke up because I had to urinate. Quickly, the problem took on an awful importance in my mind and I thought it was a tragedy. But it turned out that it was hardly a problem at all. I disconnected the electrode wires at the junction box with the help of the technician on duty, carried them in my hand, and went to the toilet. The wires were plugged in again when I was back in my room, and that was that.

I got to sleep in perhaps 15 minutes and only awakened, as far as I know, three or four times until the moment when I got up for good in the morning. That was quite different from the night before when, I believe, I slept for ten or 12 minutes at a time, waking up pretty often.

HAURI: Patients are always told inadvance that they will be able to,and will be expected to, simulate,quite closely, sleeping conditions athome. But in their state of excitementand maybe expectancy, someforget about this.

After breakfast of my second day in Hanover, I remembered wishing during the night that I had done more walking the day before. This time I did. I played tourist at Baker Library, doing a walk-by of the Orozco murals for perhaps the thousandth time. Like all good tourists I went through the Tower Room, rather happy to see so many students sleeping and reading, and I did more or less the same thing in the various parts of the campus. I went all through the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, for example, taking in a great deal that I hadn't seen before. I went to Tuck and was astonished to get an idea of what Murdough Center is like. Then I went to the new Fairchild science area and enjoyed that.

I kept fairly busy or, I should say, in motion, pretty much all day long, enjoying it a great deal. An exception to this was a period I spent with what now is known as the pinging machine at the sleep clinic. I'll say more about this later on. Perhaps I should backtrack a bit because I might have given the impression that the sleep lab consisted solely of having brain waves and other medical-scientific things about me recorded on the polygraph paper. That certainly wasn't so. Shortly after breakfast on my second day I had a lengthy meeting with Hauri and, from what I could tell, this was quite an important part of the three-day, three-night session. He had with him the lengthy questionnaire - my history of insomnia and personal matters. He did ask some questions, but mainly he simply invited me to talk about the way for years I had had trouble, not only getting to sleep, but staying asleep. Among the things that he explained was that I was what I would call a true insomniac. My problem with sleep was not caused by a psychological hang-up or something purely medical, say, like pain from arthritis. For some reason, I have trouble getting asleep and staying asleep and, to put it in the vernacular, that's what Hauri's sleep clinic is about - trying to find the cause of such a problem and then treating it. Although I'm certainly not medical and not very scientific, I should perhaps mention that I knew that the result of my stay in Hanover was not going to be a prescription for sleeping pills. Hauri, of course, will have something to say about that.

As for my third night in the sleep clinic, it is not too difficult to summarize it. On the other hand I can't say that I slept what might be called normally just because I had adjusted somewhat to being where I was and had met and got to know the director and his clinic. As I had on my second night, I read, I had a sandwich before I turned out the light. I did get to sleep in what I would judge to be perhaps ten minutes, and I remember wakening just once for sure before becoming fully awake around 6:30 in the morning.

During my third day I did see some more of Dr. Hauri and I had another go at the pinger.

Now that I'm going to talk about the mysterious thing called biofeedback, I must for the second time stop and recall that I had learned something very important when I had the lengthy interview with Hauri the day before. The subject of tenseness, naturally, came up, and Hauri revealed that he and at least one or two other prominent sleep researchers have learned that there is not a direct connection between muscle tension and insomnia per se. Insomniacs can have the problem of tenseness when they are struggling to get to sleep, but it has been shown that it is not a cause of wakefulness in most cases. This is not generally known either inside or outside the medical profession, and it was a great revelation to me to learn that tenseness at night will not necessarily prevent me from getting to sleep and staying asleep normally.

HAURI: In the physical aspects of theresearch we do on individualpatients, we must mention some newand important findings other thanthe fact that tenseness is no morepart of the make-up of insominiacsthan of other people. There is apnea,and it is a problem of men. It meansthat as soon as some men get tosleep they stop breathing. It canhappen as often as 500 times in asingle night. Then they often wakeup and have to fall asleep all overagain. In other cases they don'twake up completely but their sleep isdisturbed. Now this, just quiterecently, has been found to be fairlycommon. It requires more researchon our part.

And now to biofeedback. This will be mysterious. A machine has been developed to help, in effect, insomniacs get their minds, their brains in a state that will result in healthy sleep. As far as I know, this new electronic machine does not have a technical name. Hauri has called it his pinging machine because when the sleep clinic patient's mind is producing the right kind of waves for sleeping, that patient, on fairly rare occasions, is rewarded by hearing the machine make a real ping.

Experiencing the attempt to produce pings is like this: electrodes are attached to your head and by wire they are attached to the "pinger." As you sit there, trying to do something you don't understand, the machine shows a red light in your face and you hear nothing. So you try to do something - mentally, I mean. And what that is you are trying to do you do not know. Think of something pleasant, think of relaxing. In some way, some kind of concentration, or perhaps even lack of concentration, will make the red light go out and pleasant yellow lights come on. Do that and perhaps after a half-hour you find the yellow light staying on, then you hear that wonderful reward of "ping."

I had two sessions with the pinger, saw a lot of red light the first time, a little yellow light, and heard one ping. That was during the first half-hour session. I had a second session before leaving Hanover and ...

considerable yellow light and, wonder of wonders, three pings! Hauri seemed delighted. It meant that whatever I was doing I had started to do something right.

I am one of only 25 people who have tried the pinger. Hauri talked about the possibility of a person producing as many as 60 pings in a half-hour. Because the trip to Hanover, for me, isn't a terribly long one, I am going to arrange to go back from time to time and see if I can become a 60-ping-per-half-hour person. Hauri seems quite confident that the result will probably be good sleep.

HAURI: Biofeedback is still a newform of sleep therapy, and there arestill unknowns. What has beendemonstrated so far is that as thepatient's sessions with the pingerprogress, his sleep generally improves.

As few as 15 sessions over a one-tothree-month period could complete successful therapy. Or, if apatient stayed in Hanover continually for a month, that could doit.

The author/alumnus is both typicaland atypical. He had not been takingmedication - "sleeping pills."Some of the clinic's patients havebeen using pills, others overusingthem. We treat both. In some cases,where the use of the pinger - whichis free - may not be applicable orpractical, medication may beprescribed by a physician in theDartmouth-Hitchcock MedicalCenter.

This subject of sleep medicationcould be discussed at length but atthis time suffice it to say that somecan be useful and helpful if not takenchronically. We note that recently inCalifornia some over-the-countersleep inducers - actually, tabletsthat are used to cause drowsiness - have been proscribed. We are not incomplete agreement, though that,too, requires rather complete discussion.

Sleep research is absolutelyfascinating. We don't even knowwhy we sleep. It's restorative,physically and mentally, but weknow that only from feeling, fromobservation. We don't know how itworks. There are many questionshere.

As stated earlier, the purpose ofour sleep clinic here is to researchsleep in order to treat patients sothat their sleep problems may beremoved. At present we operate theonly such clinic in New England andwe hope to treat insomniacs from allover the six New England states.

B.K. Thorne '38, "a more or less typical insomniac," was communications officer of the Dartmouth Medical School when Dr. Hauri established his sleep clinic there. He has based this first-person narrative partially on his own experiences as a patient in the "three-night course" for insomnia treatment and as an alumnus returning to Hanover after an absence of many years. Nancy Decato, who has written drama criticism and poetry, is a member of the Baker Library staff.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

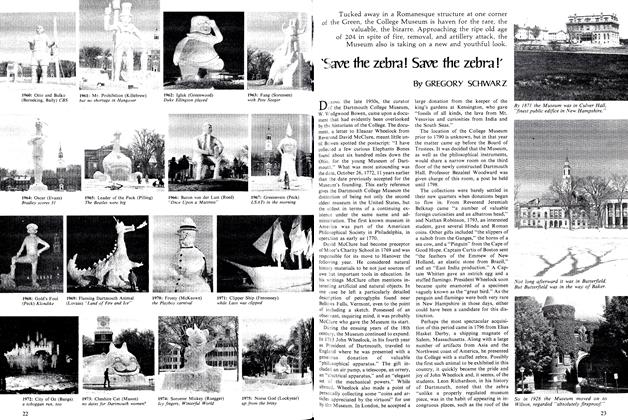

Feature'Save the zebra! Save the zebra!'

February 1976 By GREGORY SCHWARZ -

Feature

Feature'... A whole pool of frustration, anger, resentment...'

February 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Feature

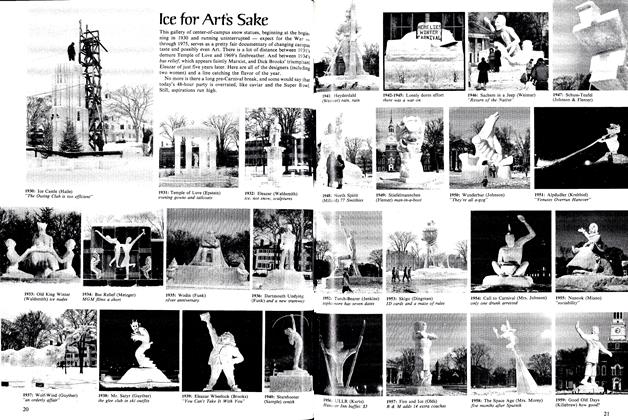

FeatureIce for Arťs Sake

February 1976 -

Article

ArticleWinter Games

February 1976 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

February 1976 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

February 1976 By JOSEPH R. BOLDT JR., EVERETT P. HOKANSON

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCarole Berger Professor of English 2 wolves in a single run

January 1975 -

Feature

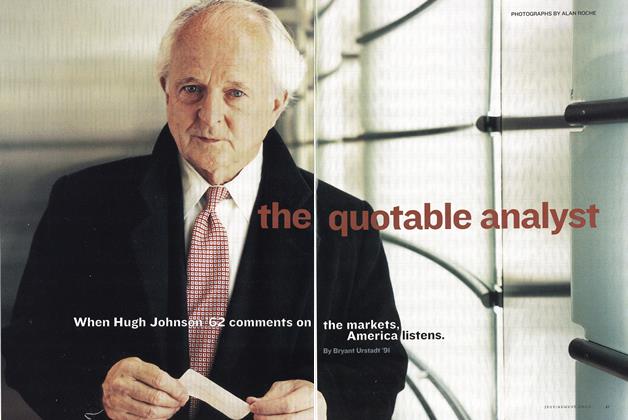

FeatureThe Quotable Analyst

July/Aug 2002 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

Feature

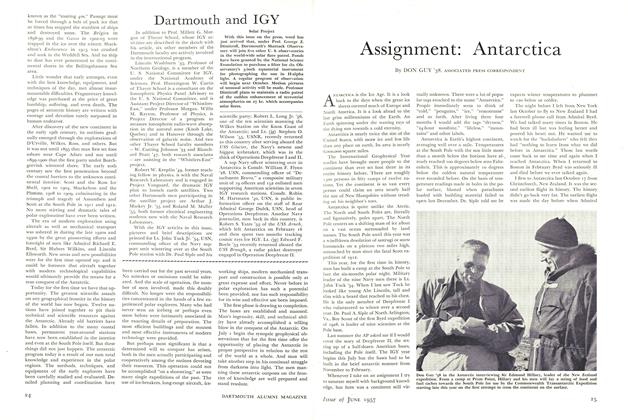

FeatureAssignment: Antarctica

June 1957 By DON GUY '38 -

Cover Story

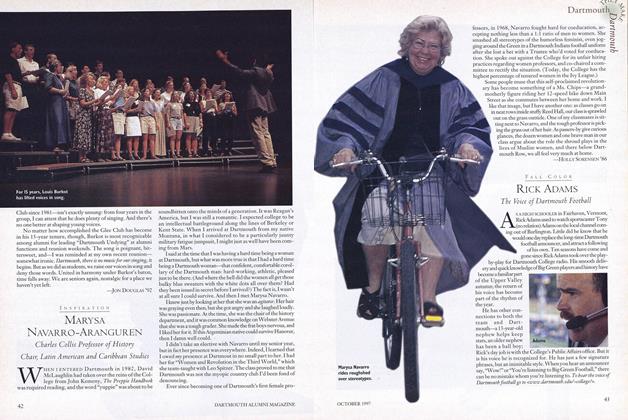

Cover StoryMarysa Navarro-Aranguren

OCTOBER 1997 By Holly Sorensen '86 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Radical Union

December 1975 By M.B.R. -

Feature

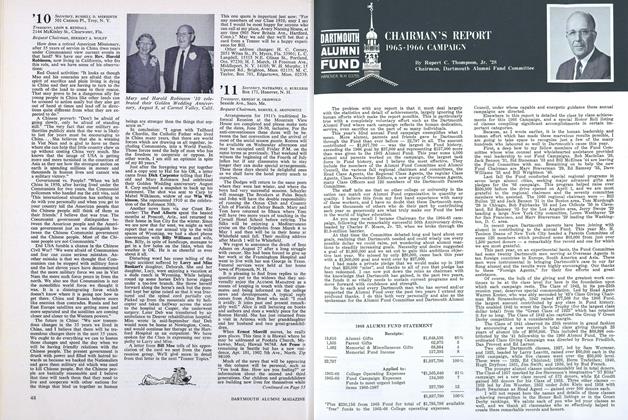

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1905-1966 CAMPAIGN

NOVEMBER 1966 By Rupert C. Thompson. Jr. '28