The title of the book is challenging. Why "existential" when engineering and existentialism appear to have nothing to do with each other? This "speculative essay" suggests that the existentialist may have trouble if he views the engineer as an antagonist whose analytical methods and pragmatic approach to life must always be "desensitizing and soul deadening... antiexistential."

If on page 4 we have references to the new marvels of transportation, communication, construction, sources of power, new materials, and conveniences of daily life, on page 5 we read how engineers are hailed as heroes by Kipling, Zane Grey, Ronald Colman, Jules Verne, H. G. Wells, Walt Whitman, Carl Sandburg, Joaquin Miller, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Henry Adams.

And then disenchantment sets in. In Berkeley 'he placard: "I am a human being - Please do not fold, spindle, or multilate." In Paris the slogan printed on the wall: "Death to the Technocrats." In the chapter "Decline and Fall" the last sentence runs: "The 'Can Do' boast of World War II years now seems as pathetic as a battered landing barge rusting on a Normandy beach."

The second half of the book treats "antitechnology," the doctrine that condemns tech- nology as the devil incarnate. Florman stands up strongly and sensibly against the excesses shown in the extravagant and anguished moans of Jacques Ellul, Lewis Mumford, Rene Dubos, Charles A. Reich, and Theodore Roszak.

Finally with the help of poetry and prose of the mo'dern era Florman encourages engineers to reaffirm their innate love for the machine because of its intrinsic beauty, for surely the machine is indeed a marvel of dynamic elegance. Breathes there an engineer with soul so dead as to be utterly unable to respond sympathetically to the power felt by the pilot of Saint-Exupery's Night Flight?

He passed his fingers along a steel rib and felt the stream of life that flowed in it; the metal did not vibrate, yet it was alive. The engine's five-hundred horse-power bred in its texture a very gentle current, fraying its ice-cold rind into a velvety bloom. Once again the pilot in full flight experienced neither giddiness nor any thrill; only the mystery of metal turned to living flesh.

Among acknowledgments Florman writes: "I also owe a debt of gratitude to the Thayer School of Engineering at Dartmouth College, where I first learned that engineering is not intended to be isolated from the quest for the good life, and where, through the years, I have observed faculty and students working at the creative and humanistic frontiers of our profession."

THE EXISTENTIAL PLEASURESOF ENGINEERING. BySamuel C. Florman '46. St. Martin's,1975. 160 pp. $7.95.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGod and Man at Dartmouth

March 1976 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

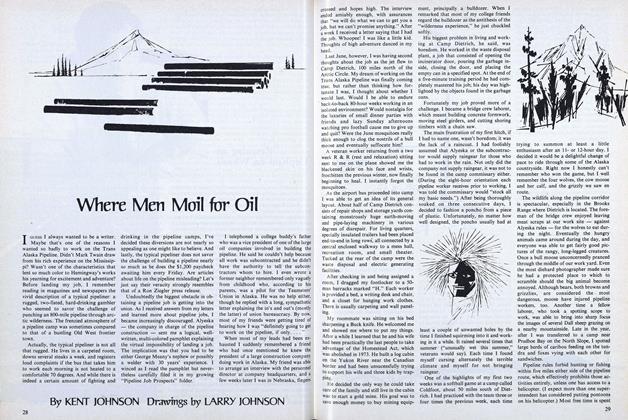

FeatureWhere Men Moil for Oil

March 1976 By KENT JOHNSON -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

March 1976 By McF. -

Feature

FeatureOPTIONS & ALTERNATIVES

March 1976 By D.N. -

Article

ArticlePeople & Places

March 1976 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

March 1976 By STEPHEN D. SEVERSON, JACK E. THOMAS JR.

JOHN HURD'21

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

April 1976 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN, G. HARRY CHAMBERLAINE, JOHN HURD'21 -

Books

BooksFIRST PERSON: CONVERSATIONS ON WRITERS AND WRITING WITH GLENWAY WESCOTT, JOHN DOS PASSOS, ROBERT PENN WARREN. JOHN UPDIKE. JOHN BARTH, ROBERT COOVER

March 1974 By JOHN HURD'21 -

Books

BooksMASTER OF THE COURTS.

May 1974 By JOHN HURD'21 -

Books

BooksALFRED LORD TENNYSON: IN MEMORIAM. AN AUTHORITATIVE TEXT, BACKGROUND AND SOURCES, CRITICISM.

May 1974 By JOHN HURD'21 -

Books

BooksThe Eye of the Beholder, Squinting

April 1975 By JOHN HURD'21 -

Books

BooksFields of Grace

September 1976 By JOHN HURD'21

Books

-

Books

Books"THE PRESTIGE VALUE OF PUBLIC EMPLOYMENT,"

FEBRUARY 1930 By Charles Leonard Stone -

Books

BooksPOLITICS IN FRANCE.

MARCH 1969 By FRANCOIS DENOEU -

Books

BooksGIRAUDOUX, THREE FACES OF DESTINY.

JUNE 1969 By FRANK BROOKS -

Books

BooksUrban Romantics

April 1976 By NOEL PERRIN -

Books

BooksSo Much More

NOVEMBER 1984 By Peter Smith -

Books

BooksPROCEEDINGS OF THE THIRD NEW HAMPSHIRE BANK MANAGEMENT CONFERENCE

October 1942 By William A. Carter '20

JOHN HURD'21

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

April 1976 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN, G. HARRY CHAMBERLAINE, JOHN HURD'21 -

Books

BooksFIRST PERSON: CONVERSATIONS ON WRITERS AND WRITING WITH GLENWAY WESCOTT, JOHN DOS PASSOS, ROBERT PENN WARREN. JOHN UPDIKE. JOHN BARTH, ROBERT COOVER

March 1974 By JOHN HURD'21 -

Books

BooksMASTER OF THE COURTS.

May 1974 By JOHN HURD'21