FIRST PERSON: CONVERSATIONS ON WRITERS AND WRITING WITH GLENWAY WESCOTT, JOHN DOS PASSOS, ROBERT PENN WARREN. JOHN UPDIKE. JOHN BARTH, ROBERT COOVER

March 1974 JOHN HURD'21FIRST PERSON: CONVERSATIONS ON WRITERS AND WRITING WITH GLENWAY WESCOTT, JOHN DOS PASSOS, ROBERT PENN WARREN. JOHN UPDIKE. JOHN BARTH, ROBERT COOVER JOHN HURD'21 March 1974

Edited by Frank Gado'58. Schenectady: Union College Press, 1973.159 pp. $9.50.

Old style: Professors orate, students jot, fast men, silent, get "A." New style: Visiting writers are challenged by articulate students egged on by the faculty. Professor Gado's introduction is invaluable, for as mature arbiter he establishes organizing principles among six novelists representing, roughly, decades of the mid-1900's, so that interviews taped and edited from their visits to the Union College campus blend into a cohesive volume. Wescott: the '20s and expatriates. Dos Passos: politicized by the War and Depression. Warren: academic leader of the '40s. Updike, Barth, and Coover: post-war representatives needing to re-invent the world. "God wasn't too bad a novelist," observes Barth, "except he was a realist." Coover challenges our vision of the world made static by traditional fictions.

Wescott, large and raw-boned, heavy jaw and heavy walk, stimulates with lightness of touch. How accurate is Gertrude Stein's reference to him as "syrup that does not pour"? Sherwood Anderson described Gertrude Stein as "a New England farm woman working in her kitchen, making word cookies." In Greenwich Village "a very typical aristocrat," liking The Apple of TheEye sent young Wescott a check for $3,000 to go to Europe with this note: "I don't want to know you or be friends with you." Wescott etchings: "Fitzgerald was an Irishman with an incredible gift of gab." Simenon is "probably the most gifted fiction writer alive." "Dostoevski was ... one of the stupidest men who ever lived, but he dreamed enormous visions of life." Updike is "one of the most fiendishly keen men I've ever known."

Dos Passos denounces the current generation as "a tantrum of spoiled children who have had too much done for them." McLuhan "jumbles his statements together - rather like a bag of eels in which you can't exactly see which are the heads and which are the tails." Dos Passos rates a good historian higher than a novelist. With the working class becoming so affluent a new layer of bourgeoisie is forming. He cares little for Steinbeck: "So much meretricious sentimentalism." Malcolm Cowley "always had a genius for getting things wrong." Hemingway's "style was a combination of cable-ese and the Holy Bible." Writers who turn university professors have more disadvantages than advantages. Dos Passos is discouraged with Barth and impatient with Mailer. Updike's Rabbit-Run is "full of talent." Vanity Fair is "a marvelous job."

Professor Gado describes Robert Penn Warren as the last major novelist cast in the Conradian mold. "... Night Rider (1939) is strikingly reminiscent of Heart of Darkness." He also points up how inevitably and strikingly Warren may be bracketed with Faulkner because of their contrapuntal narrative wordiness, lush rhetoric, and mythic portrayal of man as a creature trapped in history.

Updike does not find Lady Chatterley's Lover in any way funny. His own Couples is not satire. "It's a loving portrait of life in America. It doesn't have a dirty sentence nor a dirty word in it." Sex in Henry Miller "is quite strident and very anti-female." "For us, Eliot and Joyce lived the lives of gods; now, the gods are down off Olympus." From Here to Eternity is a good book, but "James Jones is really quite a bad writer." Black writers are so irascible that they are cut off "from novelistic invention or concern with the aesthetics of novel writing. Even Baldwin." Updike was so offended by the galleys of Catch-22 that he threw them into the trash can and so awed by Sot-Weed Factor that he calls the mimicry "really incredible." In the film Rabbit-Run, Janice, "a dumpy, nasty-looking little brunette," becomes "a very soft, nice-looking blonde."

According to Professor Gado, Barth, "dazzlingly talented," seems obligated "not to make credible but to fascinate." He has ranged from the black humor of his first two novels to the parodistic Sot- Weed Factor and Giles Goat-Boy to the retelling of myth in his recent groupings of short stories. Barth himself believes that Sot- Weed Factor has a better plot than Tom Jones. He is persuaded that there is nothing wrong with Nabakov seeking aesthetic bliss and everything wrong in a novelist moraliz- ing about our involvement in Viet Nam.

And the future? Professor Gado believes that "the irrational geometries of cerebral delight" offered by the Coovers and Barths can never command a public commensurate with that which read Hemingway and Fitzgerald, or even James or Hawthorne. "Mass culture so inhospitable to intellectual refinement may permit writers to ignore mass audiences and explore their, own trails less travelled by and thereby reinvigorate the art of the novel."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureJournal of a Long Season

March 1974 By TOM EGGLESTON -

Feature

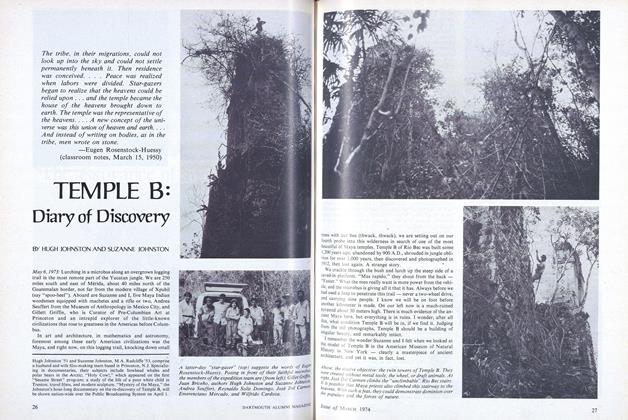

FeatureTEMPLE B: Diary of Discovery

March 1974 By HUGH JOHNSTON AND SUZANNE JOHNSTON -

Feature

FeatureConduit for the Faith)

March 1974 -

Feature

FeatureDelivery Man

March 1974 By M.B.R. -

Feature

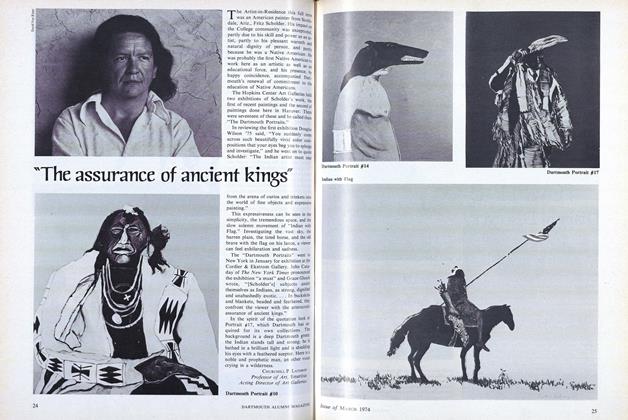

Feature"The assurance of ancient kings"

March 1974 By Churchill P. Lathrop -

Article

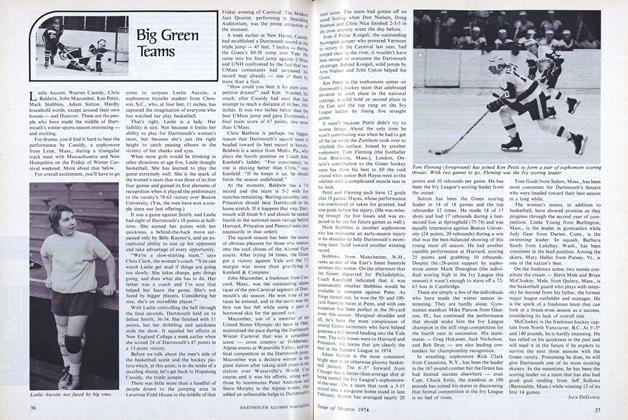

ArticleBig Green Teams

March 1974 By JACK DEGANGE

JOHN HURD'21

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

April 1976 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN, G. HARRY CHAMBERLAINE, JOHN HURD'21 -

Books

BooksMASTER OF THE COURTS.

May 1974 By JOHN HURD'21 -

Books

BooksALFRED LORD TENNYSON: IN MEMORIAM. AN AUTHORITATIVE TEXT, BACKGROUND AND SOURCES, CRITICISM.

May 1974 By JOHN HURD'21 -

Books

BooksThe Eye of the Beholder, Squinting

April 1975 By JOHN HURD'21 -

Books

BooksMetals and Living Flesh

March 1976 By JOHN HURD'21 -

Books

BooksFields of Grace

September 1976 By JOHN HURD'21

Books

-

Books

Books"The Loco-Weed Disease,"

NOVEMBER 1929 -

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

DECEMBER 1971 -

Books

BooksCATHOLICISM AND AMERICAN FREEDOM

June 1952 By FRED BERTHOLD JR. '45 -

Books

BooksOTHER LOYALTIES, A POLITICS OF PERSONALITY.

MARCH 1969 By GENE S. CESARI '52 -

Books

BooksSOMMETS LITTBRAIRES FRANÇAIS.

June 1957 By HUCH M. DAVIDSON -

Books

Books"Hanover Poems"

JUNE, 1927 By R. A. Lattimore '26, A. K. Laing '25