It was 1944 when EDWARD F. HAMMEL JR. '39, freshly minted Ph.D. in hand, headed west for Los Alamos, New Mexico, which in little more than a year had already become a magnet for the best and brightest of America's scientists and European colleagues who had fled Nazi persecution.

It was an extraordinary community, that fenced high-desert mesa where the Manhattan project was still to bear its strange fruit. The laboratories and quarters were a former boys' school, with hastily constructed barracks, prefabs, and trailers added; the address was a post-office box in Santa Fe. Personnel were permitted no direct contact with non-resident relatives; their mail was censored; drivers' licenses and income-tax returns of key men bore code names to avoid disclosure of their real identities.

Still extraordinary, Los Alamos has now been designated - along with the likes of Lexington and Concord an official Bicentennial Community. The town, though not the lab, has been open to the public since 1957. Tourists flock to view the science museum, to picnic and camp near where it all happened. Many of the chemists and the physicists - and the hyphenated variations thereof - who won the race to develop the atomic and the hydrogen bombs, which they saw, and most still see, as a race for national survival, have left. But perhaps 30 of them, including Ed Hammel, have remained as the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory has, in part, beaten its swords into peaceful scientific tools.

A junior Phi Beta Kappa who graduated with highest distinction in chemistry, Hammel made his way through Dartmouth working for Secretary of the College Sidney Hayward '26 and at one of the town eating clubs. He went on to graduate school at Princeton, completing his thesis research on the physical chemistry of protein molecules.

While still at Princeton, Hammel started working for the Manhattan Engineering District - under which the wartime Los Alamos project was eventually established - first on the process of the separation of heavy water, later on the separation of the uranium isotopes. With John Turkevich '28, he was honored by the War Department for his contribution at Princeton toward the development of the atomic bomb, an award announced long after the fact because of the highly secret nature of the work.

His wartime research at Los Alamos involved the preparation of pure metallic plutonium; after the war he became leader of a group organized to study the properties of that new element, work which eventually led to the field of low-temperature physics and chemistry and the properties of material at high pressure. "At very low temperatures," Hammel explains, "macroscopic quantum effects dominate the properties of the light elements, particularly of helium of mass three." He and his colleagues were the first to liquefy helium three and to determine its properties, accomplishments which earned him an award from the American Chemical Society.

Involved in energy-related research and development since 1972, for the past two years as LASL's assistant director for energy, Hammel was responsible for organizing two major cryogenics (science of very low temperatures) projects. One, the Superconducting Power Transmission Line project, he says, "will, if successful, permit very large blocks of electric power to be transported from generating plant to load center at much higher efficiency than present-day overhead technology, in a more environmentally acceptable manner [underground lines with no visual pollution and external electromagnetic fields completely cancelled], and under conditions such that much smaller rights-of-way will be required." Believed now to be economically competitive, these lines are scheduled for a practical demonstration in the early 'Bos. In the second major project, an attempt is being made to develop large superconducting magnets capable of storing electrical energy during off-peak hours and delivering it back to the utility grid when needed. Such storage devices, Hammel explains, are essential to the development of solar electric systems and will permit other types of generating plants to operate at a constant, hence far more efficient, power level, regardless of the fluctuating load. In 1974, Hammel's responsibilities were extended, beyond the cryogenics projects, to include the geothermal, solar, and energy-systems studies; as assistant director for energy, he is now involved also in Los Alamos' nuclear-energy programs.

Although investigation aimed at advancing the technologies of energy, health, space, and other peaceful enterprises and the basic research that underlies them all now account for more than half the LASL budget, weapons development remains its largest single program, a ratio Hammel considers optimal and likely to continue. As a veteran of the wartime programs, he has no doubts as to the wisdom of developing the atomic bomb, proceeding with the hydrogen bomb, and continuing weaponry research. "World peace - peace relative to a thermonuclear holocaust, at least - has been maintained since the USSR reached relative parity with the U.S. in nuclear arms by our maintaining the posture of 'mutually assured destruction,' " he notes. "Whether this strategy will continue to be viable no one of course knows. It has worked so far. . . ."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

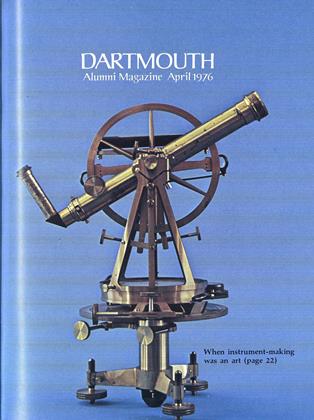

FeatureWORDS AND PICTURES MARRIED The Beginnings of DR.SEUSS

April 1976 By Edward Connery Lathem -

Feature

FeatureStrangers in the House?

April 1976 By RAYMOND L.HALL -

Feature

FeatureLap After Grim Lap, Note After Sparkling Note

April 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Feature

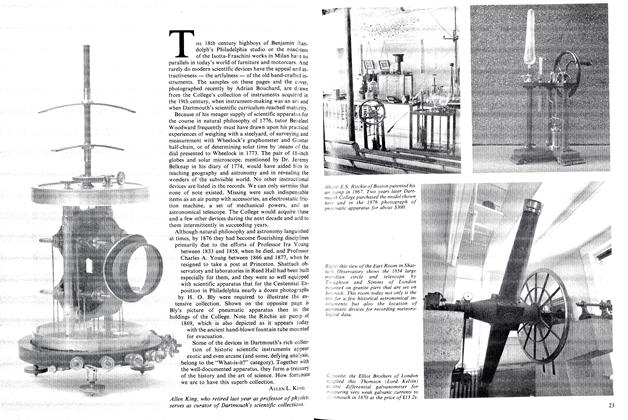

FeatureTHE 18th century highboys of Benjamin Randolph's

April 1976 By ALLEN L. KING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

April 1976 By GILBERT F. PALMER IV, FREDERICK H. WADDELL -

Article

ArticleVox Clamantis et Clamantis; or College Bites Man

April 1976 By TERENCE R. PARKINSON '71