As I write this column, on a balmy spring Hanover Saturday, a Building and Grounds crew is quietly replacing the sod, churned up by thousands of feet during the May 6 building seizure, in front of Parkhurst Hall. A few days ago, other B & G workers packed wood putty into holes made when the occupiers nailed shut Parkhurst's heavy oak doors, and soon there will remain no physical trace of the 12-hour takeover that carried Dartmouth into the ranks of a growing group of "disrupted" American universities.

The campus is quiet now, for as disruptions go ours was a mild one, humanely if firmly met by the administration. Unlike similar incidents at Columbia, Cornell and Harvard, the event at Parkhurst has caused few permanent scars, and those few, received by 32 undergraduates to date, were imposed by the courts, not by Dartmouth.

As the now-common scenario played itself out, the College community went through stages of shock, dismay, selfpity, indignation; and now, as the College judiciary prepares to wreak its vengeance upon the sinners, we are all tired of the talk and the confusion and the crisis atmosphere. It is easy to hope for a speedy conclusion of the whole affair, so that we may sink back into our normal stupor.

It would be easy but it would be a foolish mistake to forget before we have fully examined what has occurred. May sixth was the date of Dartmouth's first disruption; unless we are prepared to make some fundamental changes in this College, there will be more. Nothing could be more gratifying to the radical hard core than inertia in the center, for inertia will ultimately bring the polarization the College avoided in May, and here as elsewhere the SDS contingent hopes to polarize the campus, making the radicalization of large portions of the College inevitable.

If the wounds will soon be gone, the issues remain unchanged. To many undergraduates and also to many faculty and some administrators - the continuing presence of ROTC programs on campus is a morally untenable link between the College and a cruel and unjust war. To many, on-campus military recruiting for Officer Candidate Schools represents institutional support for American Vietnam policy. To many, not only the policies but also the process is immoral. Vincent A. Ferraro '70, a left-liberal International Relations major and president of the Dartmouth Forensic Union, voiced this widely held opinion of the faculty's decision to eliminate ROTC programs after current military contracts with undergraduates are fulfilled: "The faculty believes ROTC on campus is morally unjustifiable, but they have given a higher priority to a contract than to this moral principle."

ROTC will eventually go or be forgotten. The Vietnam war will, eventually, end. But it is this last issue, the question of process, that is fundamental. Senator Edward M. Kennedy argued in May that the burden of dissuading the moderate student majority from "indiscriminately following leaders whose goals are not their own" falls upon the university policy makers, who must initiate accelerated reforms.

"They must provide an alternative route toward change, besides the confrontation politics of the militants. And it must be real, substantial change," Senator Kennedy said. "The faculty and the administrators must become the activists, seeking out opportunities for progress, and providing the leadership and the example the student body really wants."

IT was unseasonably cold outside Parkhurst Hall the night of the occupa- tion. Over a thousand students, faculty, administrators, and local residents shivered and waited for the state troopers to come. Those inside the building carried wood out to the onlookers, courtesy, I suppose, of the fireplace in President Dickey's office.

Many of those waiting were sympa- thetic to the occupiers and occasionally those inside Parkhurst would punctuate the muffled conversation with a plea that their supporters remain until they were removed. A little panicky now, the occupiers wanted moral support - and witnesses to what they expected would be a brutal police action. More than once they bullhorned this message out: "We intend to stay until the cops flush us out. It will be the College that uses violence, the institutional force of the state." This from students, at least some of whom had physically ejected College officials from their own offices as a moral gaesture. Their force was not illegitimate; force against them was.

There is no dilemma here. For most of the occupiers, Dartmouth's rules prohibiting the occupation were inherently illegitimate because they were arrived at undemocratically. The faculty's disposition of the ROTC issue lacked legitimacy precisely because it was the faculty's decision. Those who were most affected didn't have a single vote.

At Convocation each September, President Dickey reminds the students: "Your business here is learning." It would be equally appropriate, however, to admonish the faculty that its business here is teaching, to inform the administrators that their business is administraton. But that would leave no one to make policy.

It would be rather silly to argue that students should "run" the College, but there is no reason why students should not control certain aspects of College policy formation. There is little strength in the argument that the faculty, being older, is more likely to act responsibly. A number of young faculty members have only a few years on the students they teach. It is argued that students lack the continuity to make policy - they are in Hanover only four years. But the mean residence of the faculty is only barely twice that of the average undergraduate, and many untenured faculty members, who vote in the faculty meetings with greater regularity than their senior colleagues, come and go far more quickly than undergraduates.

Writing in The Dartmouth a week after Parkhurst's occupation, Alan F. Gordon '69, a student moderate, said: "If in fact the College really wishes to convince students that there is something good to be said for contemporary society [the] rather casual attitude toward student participation must change. According to my calculations, student tuition payments for 1968-69 total just under $7 million and that seems to me to be sufficient reason for giving students a share in the decision-making process at this institution."

THERE has so far been only minor progress toward reform. The Campus Conference, an agency of students, faculty, administrators, and Trustees, is a forum, not a policy-making body. The highly publicized referendum on ROTC - though a significant step - still left all decision-making power in other hands. To date, only on the student judiciary, the College Committee on Stand- ing and Conduct, do undergraduates have a direct, substantial policy role, and they are a minority even on that committee.

Individual faculty members frequently decry the burdens of policy-making. Would that they could, they say self- righteously, drop the whole policy bag and devote themselves unstintingly to their academic pursuits. Yet it is the faculty more than the administration or Trustees who have blocked nearly every effort at reform. In the final faculty debate on ROTC, a minority of faculty members used parliamentary manipulation to kill a proposal that students be permitted to listen to their debate. Moreover, in the eyes of many students, the faculty has repeatedly bungled the job. The faculty's handling of the ROTC is- sue in particular, they claim, is a case study in indecision and misunderstanding.

To give the College's rules legitimacy, we must legitimize the process by which the rules are made. And this means nothing less than giving the undergraduates and the growing number of graduate students a vote. Undoubtedly, there are a number of ways of accomplishing this. One of the most direct would be to vest policy-making power in a body composed of equal parts of faculty and students, elected at large by their respective constituencies, with the President and Trustees forming a final, veto-holding executive body. That is, a representative faculty-student senate.

The university is under fire, and we have arrived at a critical juncture. Like it or not, we have to act or face the consequences. And, having gone this far, the consequences, no matter how deplorable, are grave indeed. The militant radicals are gaining strength, and the moderate majority is being polarized. As we sit back nodding our heads we are increasing the likelihood that we will be called upon to pick up the pieces, and that is one obligation that I, for one, do not seek. Should we wait any longer to reform, the scars will become permanent.

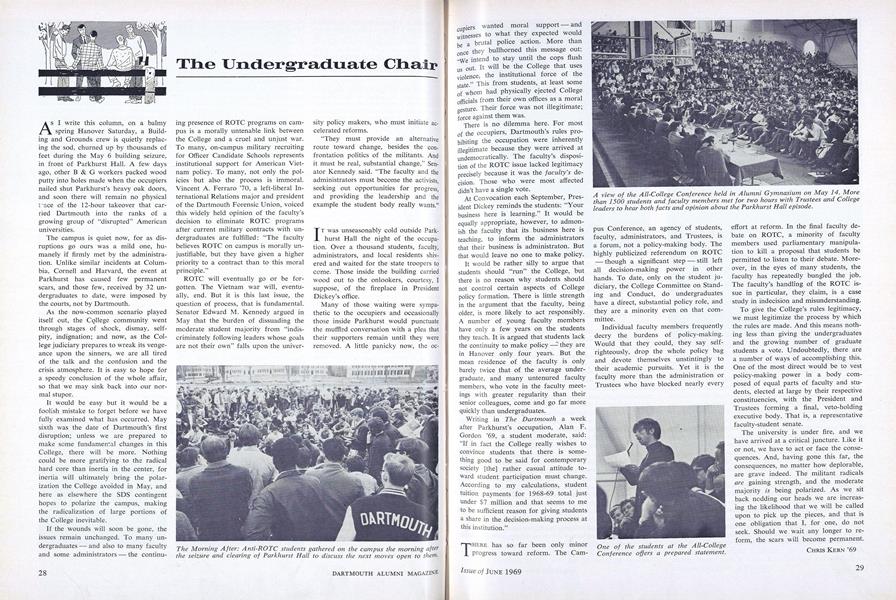

The Morning After: Anti-ROTC students gathered on the campus the morning afterthe seizure and clearing of Parkhurst Hall to discuss the next moves open to them.

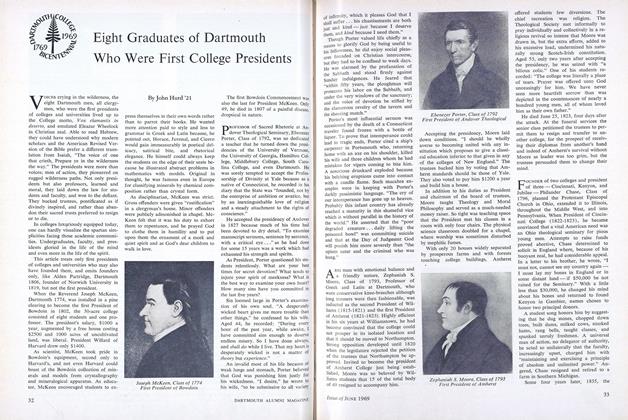

A view of the All-College Conference held in Alumni Gymnasium on May 14. Morethan 1500 students and faculty members met for two hours with Trustees and Collegeleaders to hear both facts and opinion about the Parkhurst Hall episode.

One of the students at the All-CollegeConference offers a prepared statement.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureEight Graduates of Dartmouth Who Were First College Presidents

June 1969 By John Hurd '21 -

Feature

FeatureTwelve Hours and Their Aftermath: The Student Seizure of Parkhurst Hall

June 1969 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureThe Class Officers Weekend

June 1969 -

Feature

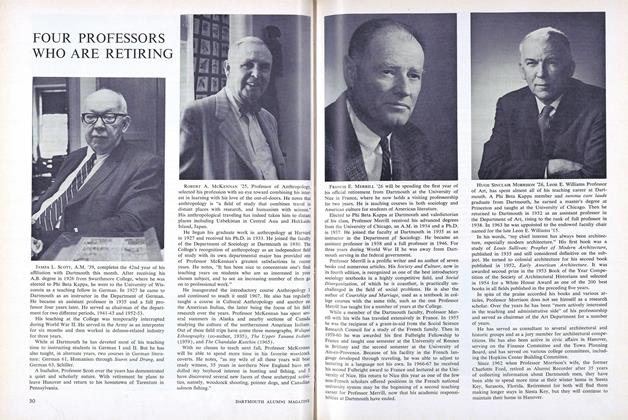

FeatureFOUR PROFESSORS WHO ARE RETIRING

June 1969 -

Feature

FeatureBicentennial Year Begins June 14

June 1969 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Awards

June 1969

CHRIS KERN '69

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

JANUARY 1970 -

Feature

FeatureVox Clamantis 1968

JUNE 1968 By Chris Kern '69 -

Article

ArticleGRANTED VOICE

November 1968 By CHRIS KERN '69 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

DECEMBER 1968 By CHRIS KERN '69 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

FEBRUARY 1969 By CHRIS KERN '69 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

APRIL 1969 By CHRIS KERN '69

Article

-

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

June 1924 -

Article

ArticleGIFTS, GRANTS & BEQUESTS

JULY 1970 -

Article

ArticleFree Will and the Virgin Spring Principle

January 1977 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER UNDER COVER

FEBRUARY 1964 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Article

ArticleMr. Brower's Bombshell

April 1952 By C. E. W -

Article

ArticleVirginia

January 1940 By Paul Gibson '15