IT was the last weekend in March, Final-Four time in Philadelphia. Like lemmings, hundreds of men who make their living as coaches of college basketball teams convened to share in the magnetic fascination that generates annually when all the games have been played and there are only four teams left in the NCAA tournament.

The atmosphere isn't conducive to decision-making, and it matters not whether you're lounging in the cushy seats at the Spectrum, watching Indiana devastate UCLA and Michigan, or killing time in the lobby of the Sheraton on Kennedy Boulevard checking the list of major college job openings that some wag has taped to a wall (joined shortly by a list that's twice as long with names of coaches who aspire to levels greater than the ones they currently occupy) - or even if you happen to be a couple hundred miles from downtown Philly.

Gary Walters hadn't planned to be at the tournament. He'd seen the tournament, played in it, he knows Philadelphia, and it's a busy time of year building for the next season. His first year at Dartmouth was more successful than even he had hoped it might be: 16-10, third place in the Ivy League, New England coach-of-the-year, a "most-improved" award for his team. People had known for a long while that Walters is a good coach. Now, he was not only good, he had another dimension to his credentials and he was breathing the scent of the big time. He was a marketable commodity and the market beckoned.

Back in the late 60s, Davidson College had twice come within six points of making it to the Final Four. It was the Lefty Dreisell Era at the Southern Conference college which has an enrollment of barely 1,000 men. Then Dreisell went to Maryland and Davidson basketball began a decline that reached 5-21 proportions last winter. Davidson wanted to get back, announced renewed commitment, and fired the coach. There were reams of applicants ready to answer the call but only a couple of candidates. The difference is that the candidate is pursued. The applicant pursues.

Gary Walters was a candidate. David- son knew his credentials as a player and coach. Walters has a demonstrated propensity for success in his sport. He was invited to consider the opportunity of engineering the "renewed commitment," and on a weekend in March, with the basketball world caught up in the electricity of the Final Four, Walters decided that for all that he had achieved in his first year at Dartmouth, there were greater worlds to conquer. As Michigan erased Rutgers and Indiana took UCLA apart, Walters made a professional assessment of his coaching goals and decided that he could find happiness, fame, and all the rest on the little campus in North Carolina that had rediscovered its basketball ambition.

In Gary Walters, Davidson thought it had the answer. After five days, Gary Walters also had answers to some fundamental personal questions that he thought had been resolved when he made his decision to leave Dartmouth. In a word, he was miserable. It wasn't Davidson per se, but the methods and philosophy a man must adopt in order to achieve the heights. Gary Walters realized that "I'm not a big-time guy. I'm a coach but I'm also a teacher."

He notified Davidson officials that he was not going to remain. He presumed he was committing professional suicide because he had no reason to believe that Dartmouth or anyone else would want him. He made contact with Dartmouth via an interested alumnus because Seaver Peters, the athletic director, was on an alumni speaking trip. His concern was for his two assistants who were out on a limb with him.

There was obvious disappointment when Walters departed Hanover. To his friends, it seemed like a wrong move. That he had made a four-year agreement with Dartmouth and was becoming the latest chapter in the revolving-door syndrome that has been Dartmouth basketball's affliction in recent years colored the situation, but the people who knew him best felt it wasn't the right time or the right place for Gary Walters.

There was little question that Dartmouth still wanted him. The door was opened within an hour of his return on April 2, a week after Walters made his original decision to leave. The discussions were fundamentally resolved within 24 hours, and the terms essentially were those he had lived with during the preceding year. After another 24 hours of soulsearching negotiations with several deans, the decision to welcome back the wandering coach was announced, and within an hour Davidson had also resolved its end of the dilemma by hiring Dave Pritchett, Dreisell's assistant at Maryland.

Basketball in the Ivy League is different from football, where competition is clearly oriented to league and regional non-league opponents, and hockey; there are less than four dozen "major" college hockey programs in the nation. Ivy League basketball is national and the competition, on the court and in the recruiting game that goes on off the court, is unlike that in any other sport.

There have been six instances since the NCAA tournament began in 1939 that an Ivy League or New England team has reached the Final Four. Dartmouth (1942, 1944) and Holy Cross did it twice, Providence and Princeton did it once. Only Holy Cross won it all (in 1947). But that's the goal, the ambition of every coach and player who competes at the national level. For the Indianas and UCLAs, it's an objective that their program is geared to achieve with reasonable regularity.

For about 90 per cent of the par- ticipants, it's the carrot on the stick. But so long as the Ivy League is qualified to pursue such lofty goals, Gary Walters will try to make Dartmouth's basketball team a legitimate entry in the quest. He'll do it within the framework (and frustrations) that are found in the league and at Dartmouth. In an era of coaching that finds longevity in one position a dying commodity, Walters will probably be at Dartmouth longer than any of Doggie Julian's successors. He may endure some lean times as he builds and teaches, but the education that he and Dartmouth received last month should make the man and the institution better for having shared in the experience.

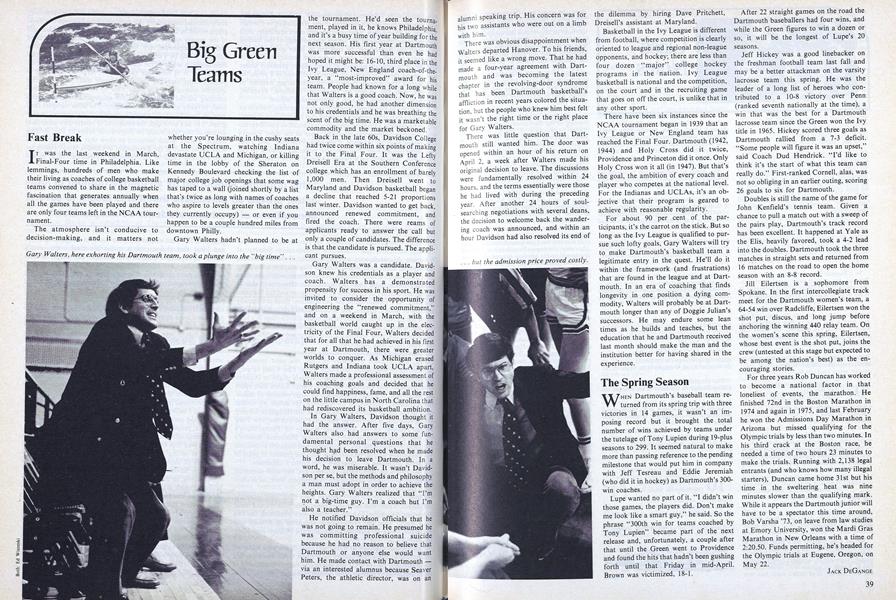

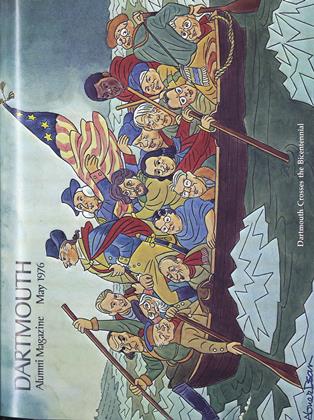

Gary Walters, here exhorting his Dartmouth team, took a plunge into the "big time"

... but the admission price proved costly.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSelf-Evident Truths

May 1976 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Feature

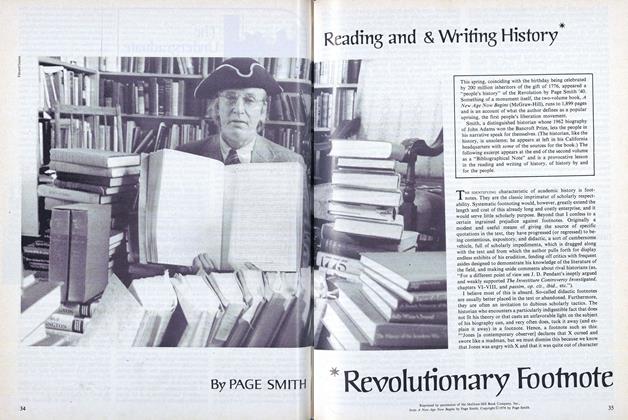

FeatureReading and Writing History and Revolutionary Footnote

May 1976 By PAGE SMITH -

Feature

FeatureWhen Dartmouth Had Its Own State (Almost)

May 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Feature

FeatureThanks to Daniel Oliver, A Gathering of Lovers

May 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Article

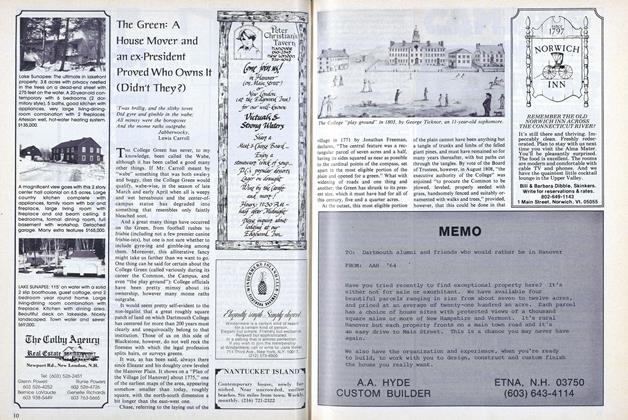

ArticleThe Green: A House Mover and an ex-President Proved Who Owns It (Didn't They?)

May 1976 By Jabberwocky, Lewis Carroll, JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

May 1976 By WALTER C. DODGE, CHARLES J. ZIMMERMAN