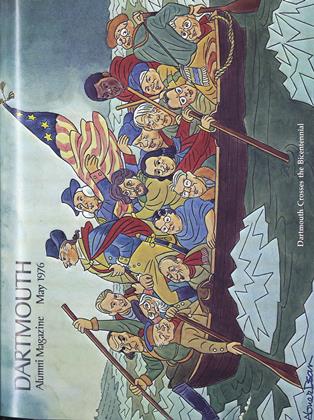

The action, Revolution-wise, around Hanover

THE YEAR 1776, we have been led to believe (and have been monotonously told for the past twelvemonth), was quite a year. The publication of Tom Paine's Common Sense, the victorious siege of Boston, the proclamation of the Declaration of Independence were all events that combined to make it a benchmark year.

The first was so because it caught the imagination of the American public and it marshaled the arguments for independence as opposed to mere redress of grievances. The second, because it was the first major campaign (as contrasted with skirmishes such as Lexington and Concord and Ticonderoga) in which the British, if not beaten, were surely frustrated. And the third, of course, because it marked the point of no return, the beyond-fail-safe of rebellion'.

There were to be five more uncertain, troubled years before Yorktown capped the struggle. Those years, and the major events in them, have been taught to us all as school children and, just for good measure, the "Bicentennial minutes" have been hammering home assorted Revolutionary trivia via the pervasive offices of the television tube.

Not to let the trivia season go without a ramble on some obscure byway and a turn-around in a cul-de-sac, here is a look into just what the action was, Revolution-wise, on the upper Connecticut River valley scene. Was the Reverend Eleazar Wheelock, what with his strong ties of power and pelf to Great Britain, a little less than enthusiastic about the Revolution? Was he, as it were, a closet Tory?

There appears to be no strong evidence that he was. On the other hand, there appears to be no copperbound testimony that he wasn't. The good divine played his political cards pretty close to his ecclesiastical robes. The best guess would appear to be that like all college presidents at all times (and particularly so for a college president of a newly founded, struggling institution), he was more concerned with finances and fund-raising than he was with politics and revolutionary philosophy.

What, then, of Hanover? And of the College community? Were they firebrands or Milquetoasts? Well, they were firebrands, some of them, enough to go against Quebec or to march to Bennington, but like northern New Englanders even today they were individualistic and prickly and they concocted their own peculiar batch of Revolutionary stew.

While, for instance, men in Boston, New York and Philadelphia (not yet realized as fellow countrymen) were turning their eyes balefully toward the mother country, Hanoverians and inhabitants of neighboring Connecticut River valley communities were considering matters more closely to home. They were, in fact, fomenting a sort of mini-revolution, which had as its targets powers in Portsmouth and Exeter in New Hampshire, Bennington in Vermont and, even at times, the more remote center of Albany, New York.

What the mini-revolutionists were after was the formation of a new state. This would be accomplished, they planned, by splitting western New Hampshire away from the Exeter-Portsmouth control and adding to it what is now eastern Vermont. Not to become the 14th state until 1791, Vermont was said to belong to New York, but the saying had not a great deal of conviction to it and New York's grasp of the region, though legal, was both tenuous and abstracted.

At the heart of the movement to create a 14th state were some officials of the fledgling Dartmouth College. Indeed, so much was the institution identified with the movement that the partisans of it, even though they came from Haverhill, Cornish, Walpole, Windsor and places in between, became known as the "College Party."

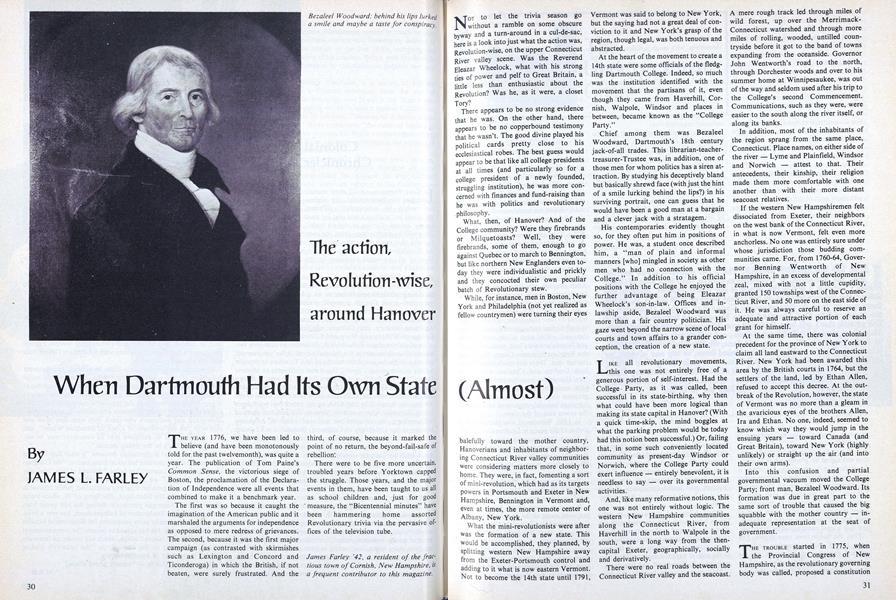

Chief among them was Bezaleel Woodward, Dartmouth's 18th century jack-of-all trades. This librarian-teacher-treasurer-Trustee was, in addition, one of those men for whom politics has a siren attraction. By studying his deceptively bland but basically shrewd face (with just the hint of a smile lurking behind the lips?) in his surviving portrait, one can guess that he would have been a good man at a bargain and a clever jack with a stratagem.

His contemporaries evidently thought so, for they often put him in positions of power. He was, a student once described him, a "man of plain and informal manners [who] mingled in society as other men who had no connection with the College." In addition to his official positions with the College he enjoyed the further advantage of being Eleazar Wheelock's son-in-law. Offices and inlawship aside, Bezaleel Woodward was more than a fair country politician. His gaze went beyond the narrow scene of local courts and town affairs to a grander conception, the creation of a new state.

LIKE all revolutionary movements, this one was not entirely free of a generous portion of self-interest. Had the College- Party, as it was called, been successful in its state-birthing, why then what could have been more logical than making its state capital in Hanover? (With a quick time-skip, the mind boggles at what the parking problem would be today had this notion been successful.) Or, failing that, in some such conveniently located community as present-day Windsor or Norwich, where the College Party could exert influence - entirely benevolent, it is needless to say - over its governmental activities.

And, like many reformative notions, this one was not entirely without logic. The western New Hampshire communities along the Connecticut River, from Haverhill in the north to Walpole in the south, were a long way from the thencapital Exeter, geographically, socially and derivatively.

There were no real roads between the Connecticut River valley and the seacoast. A mere rough track led through miles of wild forest, up over the Merrimack Connecticut watershed and through more miles of rolling, wooded, untilled countryside before it got to the band of towns expanding from the oceanside. Governor John Wentworth's road to the north, through Dorchester woods and over to his summer home at Winnipesaukee, was out of the way and seldom used after his trip to the College's second Commencement. Communications, such as they were, were easier to the south along the river itself, or along its banks.

In addition, most of the inhabitants of the region sprang from the same place, Connecticut. Place names, on either side of the river - Lyme and Plainfield, Windsor and Norwich - attest to that. Their antecedents, their kinship, their religion made them more comfortable with one another than with their more distant seacoast relatives.

If the western New Hampshiremen felt dissociated from Exeter, their neighbors on the west bank of the Connecticut River, in what is now Vermont, felt even more anchorless. No one was entirely sure under whose jurisdiction those budding communities came. For, from 1760-64, Governor Benning Wentworth of New Hampshire, in an excess of developmental zeal, mixed with not a little cupidity, granted 150 townships west of the Connecticut River, and 50 more on the east side of it. He was always careful to reserve an adequate and attractive portion of each grant for himself.

At the same time, there was colonial precedent for the province of New York to claim all land eastward to the Connecticut River. New York had been awarded this area by the British courts in 1764, but the settlers of the land, led by Ethan Allen, refused to accept this decree. At the outbreak of the Revolution, however, the state of Vermont was no more than a gleam in the avaricious eyes of the brothers Allen, Ira and Ethan. No one, indeed, seemed to know which way they would jump in the ensuing years - toward Canada (and Great Britain), toward New York (highly unlikely) or straight up the air (and into their own arms).

Into this confusion and partial governmental vacuum moved the College Party; front man, Bezaleel Woodward. Its formation was due in great part to the same sort of trouble that caused the big squabble with the mother country - inadequate representation at the seat of government.

THE TROUBLE started in 1775, when the Provincial Congress of New Hampshire, as the revolutionary governing body was called, proposed a constitution for the state in which Hanover and other towns in the western part of the state would not each have representatives, but would be clubbed together in clutches of towns, each clutch to have one representative. Given the tenor of the times, it is not surprising that the western towns vigorously opposed such a constitution (Patrick Henry and all that).

As 1776 ran down, most of the Connecticut River valley people were disenchanted with the prospect of rule by the Exeter legislature. Indeed, a convention of the Committees of Safety of 11 presentday New Hampshire towns was called on July 31 of that year at Hanover "to assume our natural right of laying a foundation of civil government within and for this colony."

There is good reason to believe that this convention hoped to bring the Wentworth grant towns east of the river into union with those west of the river and to form a new state. So high was the resentment against the provincial legislature that the convention declared that resistance to Exeter was of equal value to resistance to Great Britain.

A broadside was issued by this convention and signed by Woodward as its clerk. Its authorship is unknown, but there is good reason to believe it was written either by Woodward or Elisha Payne of Lebanon, like Woodward also once a treasurer and Trustee of Dartmouth. It asked that every inhabited town have at least one representative in the legislature, and that a legal constitution be drawn up.

Thus the battle lines were drawn. The lines would shift somewhat and the political objectives might change, but the Connecticut River valley towns would remain in rebellion and flux for the next seven or eight years - a tumultuous time.

They were never in rebellion against the aims of the larger cause of independence from Great Britain. Indeed, they regarded themselves, with much justification, as the bulwark to the north against British (and Indians) poised in Canada. Their first object of rebellion was Exeter and the seacoast interests. The Aliens and those pushing for statehood for Vermont, known as the Bennington Party, were a later and secondary object of contention. New York soon dropped out of the contest as a seriously regarded rival.

Gradually the emphasis shifted from the 1776 mood of seeking redress from Exeter to a 1777 feeling for political independence from New Hampshire. Then the College Party shifted to a plan whereby the towns east of the river (present-day New Hampshire) would throw in with their friends west of it in the formation of Vermont and, in effect, take it over. Again, it was hoped, the capital of the state would be Hanover (or Dresden, as the College Party was now calling the College section of town). With this in mind, 16 New Hampshire towns, including Hanover, early in 1778 petitioned the Vermont assembly for admission to the aborning state. They were accepted in June of that year, despite objections of the Allen brothers, who feared domination of their new state by the Connecticut River valley towns.

Ethan Allen was not a man to take things lying down. He connived with the Exeter leaders and used pressure from the Continental Congress to convince the Vermont Assembly to reverse itself. He was, in the end, to have too much political firepower for B. Woodward and friends.

This reversal again brought the New Hampshire towns, along with ten towns west of the river, back to the notion of forming a new independent state. They met for that purpose at a convention at Cornish, New Hampshire, in December 1778, with Woodward and Payne once again in the forefront. Further, John Wheelock was dispatched to Philadelphia to thwart the Vermont aspirations.

However, the Cornish conventioneers left a small kedge anchor out. They said, in effect, that if all else fails we will consider joining New Hampshire, provided an acceptable form of government could be arranged.

The fledgling Congress, when faced with the conflicting claims of New York, New Hampshire, Vermont, and the league of river valley towns, did what Congress has often done since in a controversy nothing. Congress was, to be fair, afraid of civil war or the alliance of Vermont with the British (the Aliens had negotiated with them) should the lands west of the Connecticut River go to New Hampshire.

FOR the next three years, push-and-haul was the political order of the day. First, a convention of 43 valley towns met at Charlestown, New Hampshire, in 1781 and voted that New Hampshire should hold sway in all the towns. The übiquitous Allen interests, this time in the person of Ira, intervened and reversed the vote the following day to union with Vermont.

By October 1782, Vermont had readmitted 35 New Hampshire representatives. It went further and organized courts, counties, and militia east of the river. Payne and Woodward were both made justices of the Vermont Supreme Court. But it was the last shot. There was much dissension in both Grafton and Cheshire counties in New Hampshire over this move and not a little antipathy toward Vermont. Under pressure from General Washington, the Vermont assembly renounced its claims to the towns east of the river.

In 1783, Woodward was reappointed a justice of the peace in Grafton County and in March 1784, he appeared in Exeter as a representative from Hanover to the New Hampshire assembly, the first one to take his seat from there in the state government.

Yorktown was 1781, the Treaty of Paris was 1783. By March 1784, not one but two rebellions were over.

It was a good thing, too. For the proposed name of the new state was New Connecticut. New Norwich, New Connecticut to identify it from old Norwich, old Connecticut - would have been too much, a name place with a redundant and tinny ring. And, besides, it would have been hell for stutterers to try to identify themselves as neo-Nutmeggers.

Bezaleel Woodward: behind his lips lurkeda smile and maybe a taste for conspiracy.

Promising "to disclose... all treasons," the New Hampshire patriots meant business.

James Farley '42, a resident of the fractious town of Cornish, New Hampshire, isa frequent contributor to this magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSelf-Evident Truths

May 1976 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Feature

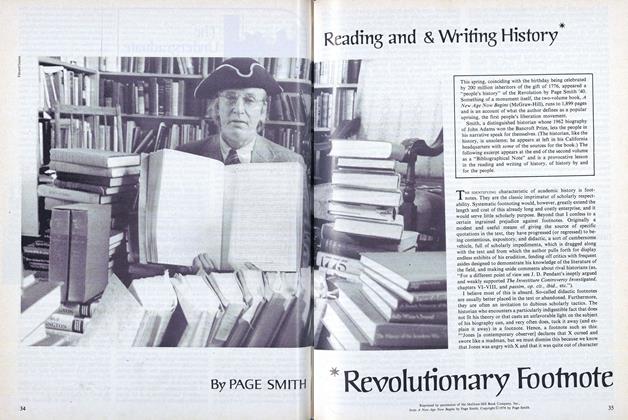

FeatureReading and Writing History and Revolutionary Footnote

May 1976 By PAGE SMITH -

Feature

FeatureThanks to Daniel Oliver, A Gathering of Lovers

May 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Article

ArticleThe Green: A House Mover and an ex-President Proved Who Owns It (Didn't They?)

May 1976 By Jabberwocky, Lewis Carroll, JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

May 1976 By WALTER C. DODGE, CHARLES J. ZIMMERMAN -

Article

ArticleFast Break

May 1976

JAMES L. FARLEY

-

Feature

FeatureOf Sun-Gazers and Seal-Hunters

JAN./FEB. 1978 By James L. Farley -

Feature

FeatureRev. Frisbie's Wonderful Discovery

MAY 1978 By James L. Farley -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

October 1947 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

February 1952 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

June 1949 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN, ADDISON L. WINSHIP II -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

March 1950 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN, ADDISON L. WINSHIP II

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryHandsome Facade

April 1981 -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

JUNE 1971 By B.B. -

Feature

FeatureThe Trustees: 15 men and a woman with ultimate authority

October 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureThe and the

November 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Feature

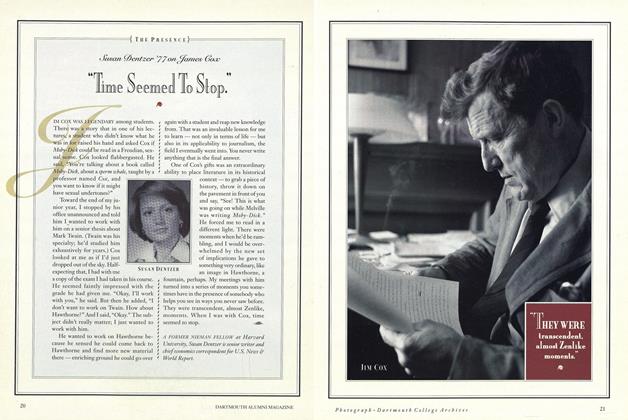

FeatureSusan Dentzer '77 on James Cox

NOVEMBER 1991 By Jim Cox -

Feature

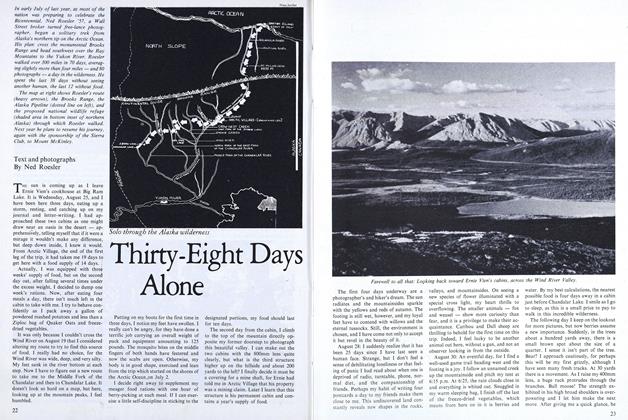

FeatureThirty-Eight Days Alone

SEPT. 1977 By Ned Roesler