THE IDENTIFYING characteristic of academic history is footnotes. They are the classic imprimatur of scholarly respectability. Systematic footnoting would, however, greatly extend the length and cost of this already long and costly enterprise, and it would serve little scholarly purpose. Beyond that I confess to a certain ingrained prejudice against footnotes. Originally a modest and useful means of giving the source of specific quotations in the text, they have progressed (or regressed) to being contentious, expository, and didactic, a sort of cumbersome vehicle, full of scholarly impedimenta, which is dragged along with the text and from which the author pulls forth for display endless exhibits of his erudition, fending off critics with frequent asides designed to demonstrate his knowledge of the literature of the field, and making snide comments about rival historians (as, "For a different point of view see J. D. Pendant's ineptly argued and weakly supported The Investiture Controversy Investigated, chapters VI-VIII, and passim, op. cit., ibid., etc.").

I believe most of this is absurd. So-called didactic footnotes are usually better placed in the text or abandoned. Furthermore, they are often an invitation to dubious scholarly tactics. The historian who encounters a particularly indigestible fact that does not fit his theory or that casts an unfavorable light on the subject of his biography can, and very often does, tuck it away (and explain it away) in a footnote. Hence, a footnote such as this: 5 "Jones [a contemporary observer] declares that X cursed and swore like a madman, but we must dismiss this because we know that Jones was angry with X and that it was quite out of character

for X to curse and swear." This scholarly dodge seems to me to be perilously close to cheating. I suspect we would all be better off if expository and didactic footnotes were banned from scholarly texts.

Be that as it may, I can say for this work that the primary sources for the history of the era of the American Revolution are well known to historians familiar with the field. I have in most places in the text stated the work from which a particular quotation has been taken, as, "Light Horse Harry Lee noted in his Memoirs of the Southern Campaign..."or "Dr. Thacher recorded in his diary...." Beyond that I have, wherever practical, given the name of a letter writer, the date or approximate date of the letter, and often the name of the recipient. With such evidence, a serious or even an interested amateur wishing to track down the full text of letter or document will be able to do so with little difficulty.

I would like to review here the primary source materials used in this work. For anyone interested in the American Revolution from the beginning of the resistance to Parliament down to 1776, one monumental work looms over all others, Peter Force's American Archives. This work in nine large volumes is an extraordinary compilation of newspaper articles, public documents, and letters dealing with the period of agitation and the opening episodes of the war. It contains literally thousands of vivid and illuminating items. Just as this present work was getting under way, Arno Books, a subsidiary of The New York Times, reprinted almost 200 volumes of "eyewitness accounts" - first-hand, contemporary narratives by participants in the Revolution. These were, almost without exception, well known, but many were out of print and difficult or impossible to get, and all are expensive in their original editions. This ambitious venture was my most valuable single resource; indeed, I often had the eerie feeling that it had been published for my express benefit. I had the

same feeling about another work, more modest in extent, but almost equally valuable; Mark Mayo Boatner Ill's Encyclopedia of the American Revolution, published in 1966. This estimable volume, clearly the result of vast labors, saved me countless hours in reference libraries hunting down information on some obscure but interesting figure in the Revolution or on some minor (or major) battle or engagement.

Also useful was Henry Steele Commager's and Richard B. Morris's Spirit of 76, a splendidly comprehensive collection of firsthand accounts of the Revolution accompanied by helpful notes (not footnotes). There are, in addition, many standard primary sources in print. Any quotation from a letter written by a delegate to Congress is almost certainly from Edmund Burnett's great collection of Letters of Delegates to Continental Congress, in seven volumes. The Journals of Congress have also been printed, but they contain only the barest record of daily business.

For the military campaigns, the principal sources are to be found in the letters and papers of the general officers involved. First and foremost, of course, is Washington's own voluminous correspondence. The (John) Sullivan Papers were very helpful, as were William Moultrie's Memoirs (especially for the siege of Charles Town) and, to a lesser degree, those of General William Heath. I have already mentioned the greatest military history to come out of the Revolution, Henry Lee's Memoirs of theSouthern Campaign. In addition, there are numerous journals and diaries, most of them by officers - American, British, and Hessian. Some of the most striking, however, are by enlisted men. Joseph Plumb Martin's Narrative was a kind of autobio- graphical recollection of the events in which he had participated and what little it may have lost in immediacy it doubtless gained in literary style.

There are four contemporary formal histories of the Revolution that are still extremely useful. William Gordon's History published in 1788, is a very good one, as is that of David Ramsay which is still unexcelled in its account of the origins of the Revolution. Ramsay's History of the Revolution in SouthCarolina is also very helpful. Charles Stedman, who was a member of Howe's staff, wrote perhaps the best overall contemporary military account of the war, especially reliable of course for those campaigns in which he participated. In addition, Banastre Tarleton wrote a kind of British counterpoint to Henry Lee's MLè's Memoirs - A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Provinces of North America, and John Burgoyne, William Howe, and Henry Clinton wrote lengthy and tendentious accounts of their campaigns that were intended to vindicate their actions (usually by putting the blame on their fellow officers). Of these Clinton's is the most successfully sustained narrative.

For the British side, Hansard's Parliamentary Debates and the Annual Register were the most useful. The nature of the AnnualRegister is perhaps best suggested by its full title, The AnnualRegister or General Repository of History, Politics, andLiterature, for the Year [whatever the year was J. This remarkable work, which was edited through a considerable portion of its life by Edmund Burke, gave a year-by-year resume of principal events in the Western world. The 1780 edition was prefaced, for example, by a "Review of the Principal Transactions of the present Reign," which had a subdued Whig note to

it. This was followed by 20 chapters on "British and Foreign History," much of it based on parliamentary debates with lengthy extracts from those debates, many of which were devoted to the American war. The next section, entitled "Principal Occurrences, was devoted primarily to firsthand accounts of naval and military engagements, along with the births, marriages, promotions, and deaths among the great lords of the realm. Then followed a section of "Public Papers" and a section entitled "Biographical Anecdotes and Characters," which reviewed the theater season and the leading books published during the year, and which contained a very complimentary "Sketch of the Life and Character of General Washington." ("Candour, sincerity, affability, and simplicity, seem to be the striking features of his character, till an occasion offers of displaying the most determined bravery and independence of spirit," the author con- cluded). Sections on the "Manner of Nations," "Philosophical Papers," "Antiquities,-" and, finally, a selection of "Poetry" completed the Annual Register for 1780. We certainly have nothing so interesting or comprehensive today.

W. E. H. Lecky's great eight-volume History of England in theEighteenth Century, while not a primary source, contains, of course, a great amount of material on America and the Revolution, most of which has been abstracted in a single volume.

The best sources for the diplomatic history of the period are Francis Wharton's Diplomatic Correspondence of the AmericanRevolution in six volumes and Benjamin F. Stevens' Facsimilesof American Documents Relating to the Revolution in ForeignArchives in 25 volumes. Also used, though more sparingly, were the numerous editions of the letters and writings of the leading figures of the Revolution. In addition to often quite adequate collections of such papers edited in the 19th century, there are a number of large-scale editions of these papers presently under way, among them the papers of Thomas Jefferson in a projected 75 volumes, the Adams Papers in an even larger number of volumes, and the papers of Hamilton, Madison, Franklin, Marshall, and Mason, each in a multivolume edition.

In addition to the printed primary source materials, there is an enormous amount of primary material that has not been printed. All of the original 13 states have historical societies and libraries. Many university libraries, especially those at the older Eastern universities such as Harvard, Columbia, Princeton, and Yale, have large collections of manuscript materials relating to the Revolution. The William Clements Library at the University of

Michigan, the Houghton Library at Harvard, the Beinecke Library at Yale, the American Antiquarian Society at Worcester, Massachusetts, and the Institute of Early American History and Culture at Williamsburg, Virginia, are among the most prominent of such manuscript repositories, with collections covering much more than the Revolution. There are, also of course, the Library of Congress at Washington and the National Archives. As I mentioned in the introduction, there are literally millions of letters, papers, and documents having to do with the era of the Revolution. No one person could absorb them in a long lifetime. It seems safe to say, however, that with, I am sure, many exceptions, the most interesting and important primary source materials have been published.

At the beginning of this work, my research assistant, Lester Cohen, and I made a journey through the most important repositories of manuscript materials on the East Coast to get a notion of what unused or little-used materials might be found in these libraries and historical societies. Lester Cohen then spent the better part of a year collecting nine large volumes of manuscript material, reproduced by Xeroxing. He struck his richest veins in the Jared Sparks manuscripts in the Houghton Library at Harvard and in the George Bancroft Papers at the New York Public Library; in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania's Laurens Papers; and in the Connecticut Historical Society's Jonathan Trumbull Papers. The Sparks and Bancroft collections were especially helpful because they were the product of years of assiduous collecting by those two 19th century historians.

The American Antiquarian Society has the most complete collection of colonial newspapers. Newspapers were, as is clear from the text, used extensively.

Most, if not all, of the 13 states have their own historical magazines. These contain many contemporary letters and other important documents. Although others were consulted, the two most useful were the Pennsylvania Magazine of History andBiography, with an excellent index, and the William and MaryQuarterly.

Still another category of works was used. These were so-called monographs, specialized studies on a single topic. The term is a loose one that covers what are essentially narrative accounts of small segments of a larger topic (although the monographs themselves may bulk very large), as well as works that are essentially analytical and interpretive. An example of the first type of monograph would be Carl Van Doren's Mutiny in January, an account of the mutiny of the Pennsylvania Line that was very detailed and, in consequence, very helpful in this work. In the same category would be Van Doren's Secret History of the AmericanRevolution, a study of the spies, double agents, and traitors on both sides. It is here that the story of Arnold's treachery is perhaps most carefully and scrupulously told. Allen French s splendid monograph The First Year of the Revolution is outstanding narrative history. Of the relatively few monographs used, virtually all were in this category. The other category (and what is usually more generally meant by the term "monograph") is, as I have said, the analytical or interpretive study. Examples of this type would be Sceptre and Mitre by Carl Bridenbaugh, a work which purports to show that religious conflicts were at the heart of the Revolution; or Gordon Wood's more recent Political Ideas of the American Revolution. Most monographs

of this kind extract from the complex tangle of episodes and ideas that characterize a major historical event certain themes or topics for detailed examination. The danger in such studies is that their authors are tempted to claim more importance for their particular "theme" than a comprehensive and balanced perspective justifies. Thus a famous and very influential monograph by Arthur Schlesinger, entitled the New EnglandMerchants and the American Revolution, argued very learnedly that the Revolution really came about because the New England merchants were determined to protect their trade. This doctrine, supported by an infinite number of footnotes, proved so persuasive that it was taught to several generations of graduate students of history as simple fact.

At worst the monograph is very apt to muddy the historical waters and draw attention away from the primary issues. At best it serves an important if transient purpose by relating historical events to the "spirit of the times," and thus keeping them accessible, at least on a scholarly level, through "reinterpretation." The writing of them also serves to keep historians occupied and to get them promoted in institutions preoccupied by "scholarship." If it is true, as I believe it is, that the truth of an event is to be found in the full and careful telling of it - that, as Erich Auerbach said, the event, properly told, contains its own interpretation standard monographic history has little meaning for a work of this kind. It was thus little used, an omission that had the incidental benefit of saving an enormous amount of time, since literally hundreds of monographs have accumulated on the era of the American Revolution.

Hopefully, at this point the reader interested in the matter of sources (which is certainly a very interesting matter) has some idea of how this history was assembled. My primary commitment from the first moment of undertaking this task has been to consult the primary sources, the words and actions - as recorded in letters, diaries, journals, newspapers, public documents, and memoirsmemoirs - of the men and women who were involved in the event out of which this nation was born. I have tried at all times to be attentive to them; to listen carefully and to reflect upon the meaning of their words and actions. Whatever virtues this work may have is the consequence of that essentially simple process - listening.

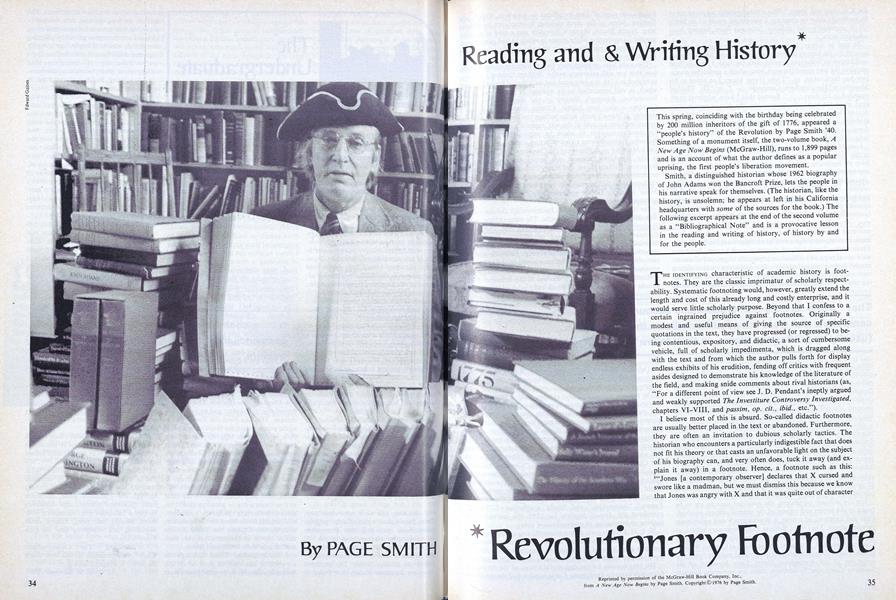

Reading and & Writing History* by 200 million inheritors of the gift of 1776, appeared a "people's history" of the Revolution by Page Smith '40. Something of a monument itself, the two-volume book, ANew Age Now Begins (McGraw-Hill), runs to 1,899 pages and is an account of what the author defines as a popular uprising, the first people's liberation movement. Smith, a distinguished historian whose 1962 biography of John Adams won the Bancroft Prize, lets the people in his narrative speak for themselves. (The historian, like the history, is unsolemn; he appears at left in his California headquarters with some of the sources for the book.) The following excerpt appears at the end of the second volume as a "Bibliographical Note" and is a provocative lesson in the reading and writing of history, of history by and for the people.

Reprinted by permission of the McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., from A New Age Now Begins by Page Smith. Copyright© 1976 by Page Smith.

They "wrote lengthy and tendentious accounts of theircampaigns that were intended to vindicate their actions(usually by putting the blame on their fellow officers)."

"This doctrine, supported by an infinite number of footnotes, proved so persuasive that it was taught to severalgenerations of graduate students as simple fact."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSelf-Evident Truths

May 1976 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Feature

FeatureWhen Dartmouth Had Its Own State (Almost)

May 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Feature

FeatureThanks to Daniel Oliver, A Gathering of Lovers

May 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Article

ArticleThe Green: A House Mover and an ex-President Proved Who Owns It (Didn't They?)

May 1976 By Jabberwocky, Lewis Carroll, JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

May 1976 By WALTER C. DODGE, CHARLES J. ZIMMERMAN -

Article

ArticleFast Break

May 1976

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Faculty

April 1975 -

Feature

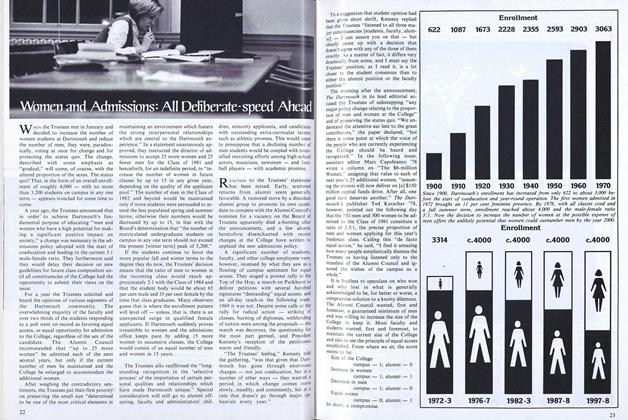

FeatureWomen and Admissions: All Deliberate-speed Ahead

March 1977 -

Cover Story

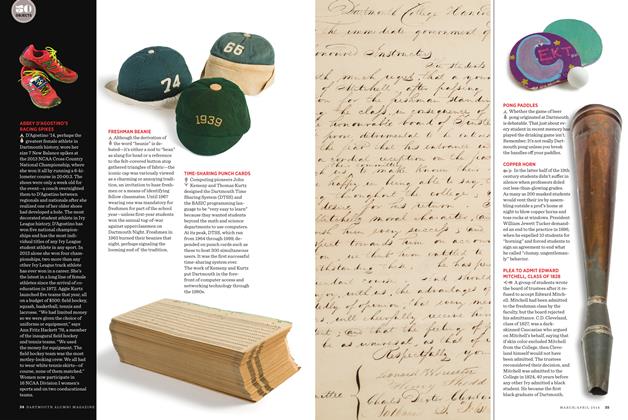

Cover StoryABBEY D’AGOSTINO’S RACING SPIKES

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

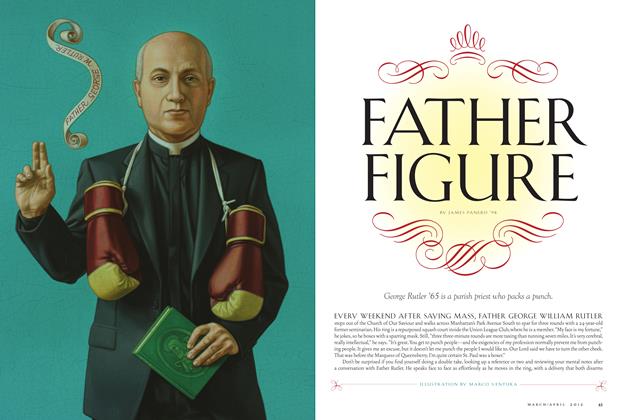

FeatureFather Figure

Mar/Apr 2012 By JAMES PANERO ’98 -

Feature

FeatureFrom the Primate Patrimony To the Fellowship of Flowers

FEBRUARY 1970 By JAMES W. FERNANDEZ -

Feature

FeatureART AT NOON

MARCH 1971 By PETER D. SMITH