The Green: A House Mover and an ex-President Proved Who Owns It (Didn't They?)

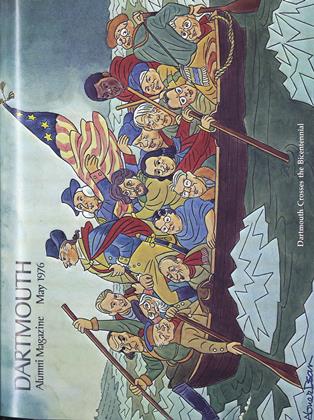

May 1976 Jabberwocky, Lewis Carroll, JAMES L. FARLEY '42The Green: A House Mover and an ex-President Proved Who Owns It (Didn't They?) Jabberwocky, Lewis Carroll, JAMES L. FARLEY '42 May 1976

'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; All mimsy were the borogoves And the mome raths outgrabe.

THE College Green has never, to my knowledge, been called the Wabe, although it, has been called a good many other things. If Mr. Carroll meant by "wabe" something that was both swale-y and boggy, then the College Green would qualify, wabe-wise, in the season of late March and early April when all is weepy and wet hereabouts and the center-of-campus statue has degraded into something that resembles only faintly bleached soot.

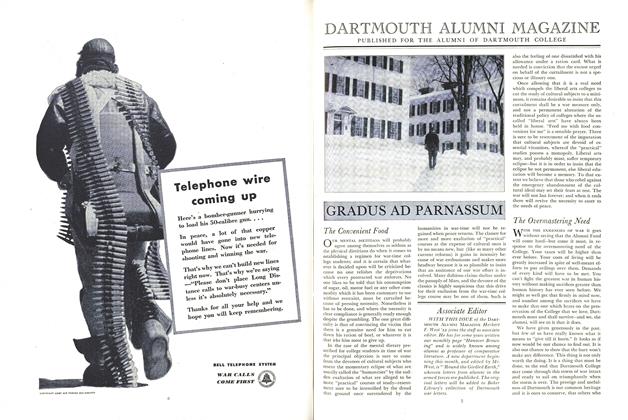

And a great many things have occurred on the Green, from football rushes to frisbie (including not a few premier canine frisbie-ists), but one is not sure whether to include gyre-ing and gimble-ing among them. Moreover, this alliterative fancy might take us farther than we want to go. One thing can be said for certain about the College Green (called variously during its career the Common, the Campus, and even "the play ground"): College officials have been pretty mimsy about its ownership, however many mome raths outgrabe.

It would seem pretty self-evident to the non-legalist that a great roughly square patch of land on which Dartmouth College has centered for more than 200 years must clearly and unequivocally belong to that institution. Those of us on this side of Blackstone, however, do not well reck the fineness with which the legal profession splits hairs, or surveys greens.

It was, as has been said, always there since Eleazar and his doughty crew leveled the Hanover Plain. It shows on a "Plan of the Village [of Hanover] about 1775," one of the earliest maps of the area, appearing somehow smaller than today, roughly square, with the north-south dimension a bit longer than the east-west one.

Chase, referring to the laying out of the village in 1771 by Jonathan Freeman, declares, "The central feature was a rectangular parcel of seven acres and a half, having its sides squared as near as possible to the cardinal points of the compass, set apart in the most eligible portion of the plain and opened for a green." What with widening of roads and one thing and another, the Green has shrunk to its present size, which it must have had for all of this century, five and a quarter acres.

At the outset, this most eligible portion of the plain cannot have been anything but a tangle of trunks and limbs of the felled giant pines, and must have remained so for many years thereafter, with but paths cut through the tangles. By vote of the Board of Trustees, however, in August 1808, "the executive authority of the College" was enjoined "to procure the Common to be plowed, leveled, properly seeded with grass, handsomely fenced and suitably ornamented with walks and trees," provided, however, that this could be done in that best of Yankee tradition, "without expense to the Corporation."

Again, at the annual Trustee meeting of 1831, it was voted "that the leveling [of] the Common on the College Plain be referred to the Prudential Committee with an authority to inclose such part of said Plain as is not improved for roads as they shall deem expedient." The leveling was promptly undertaken (had the 1808 vote not been acted upon, or had the job been done unevenly?), but the fencing, according to Lord's history, was not completed until 1836.

But that niggling question of roads across the Green had raised its head and Lord refers to it twice again. In 1844, he says, "The rum party retorted by an article in the warrant to lay out a highway across the Common.... The proposition to destroy the highway was lost by a still more overwhelming vote." And, in April 1873, one of those town-gown fights erupted (what more touchy time is there in the northern New England calendar than April?). The town had pared away about 30 feet of the southern edge of the Common (as it was then called) to straighten the road line between East and West Wheelock streets. To effect this they moved the existing southerly fence 30 feet to the north.

This outraged the students, already beset by mud season and the megrims. So they tore down the fence and burned it. "The burning of this fence," Lord says, "caused a great commotion and the selectmen threatened to open the road which formerly had passed diagonally through the Common from the hotel to the present chapel corner, and which had never been legally discontinued. The College authorities thought it wise immediately to replace the fence rather than to allow the town to do it and thus raise the question of title, or to have any controversy over the road."

Another sort of question of title was settled on March 17, 1906, when the Trustees voted "that the name 'campus' be changed to 'College Green'; and that hereinafter in College publications and maps and plans of land and buildings, the name of 'College Green' be substituted for 'Campus.' "

But it must have been this shadowy threat of ownership title and not-legally-given-up roads looming that caused a rather extraordinary action by expresident William Jewett Tucker, on August 28, 1909.

"As I came down the street," he noted in a communique to the clerk of the Board of Trustees, "I noticed that a building about 30 ft. by 20 ft., the ell of the Kappa Kappa Kappa House, was placed on the northwest edge of the College Green with the evident intention of moving it diagonally across the Green." President emeritus or not, the Reverend Tucker was galvanized into action. He called the attention of the College treasurer to the threatened transit of the Green, and he got in touch with the chairman of the board of precinct commissioners of Hanover.

The upshot was that the mover of said building ell, one Mr. Sargent, had to wait, hat-in-hand, upon the College treasurer and formally ask permission to transit the Green. He got it easily (and orally), but exPresident Tucker, in the conclusion of his communique, noted portentously:

I report this incident as of consequence in fixing the control of the tract of land known as the College Green. The Precinct Commissioners of their own will denied their authority by referring the application made to them to the College authorities, and the treasurer of the College, acting in behalf of the Trustees, assumed authority by giving permission for the moving of the building. It is assumed that the permission thus granted will not be accepted as a precedent for like use of the College Green in the future, unless it may be for the moving of College buildings. The decision of the large question involved, that of the control of the Green, seemed to warrant the permission given as it definitely locates, according to present understanding, the control of the College Green.

This was certified to be true by the treasurer of the College and sworn to before a justice of the peace.

A similar reaction was elicited a few years later from one Homer Eaton Keyes, business director of the College (Dartmouth by then was heavily into its tripar- tite name phase, touched off by none other than William Jewett Tucker). This time one H. M. Clifford was proposing to move a barn across the Green, but starting his transit from the opposite, or southeast, corner. He, too, had to get a permit (this time in writing) from Keyes ("for which he thanked me") and to promise to be responsible for any property damage to the Green.

An earlier action, taken at a legal town meeting of Hanover, May 19, 1824, might have obviated all this worry about the "control of the tract of land known as the College Green." It said that the adoption of an ordinance which forbid the "playing 'at ball or any game in which ball is used' be applied to the highways, streets, lanes and alleys only, and not to the public com mon in front of Dartmouth College, set apart by the Trustees thereof, among other purposes for a play ground for their Students."

And there it rests. Today the only vehicles driven over the green are the snowplows and trucks of Buildings and Grounds (and an occasional car by an elevated student). The Green remains "a play ground for their Students" and an arena for romping, fighting, and orgies by Hanover's canines.

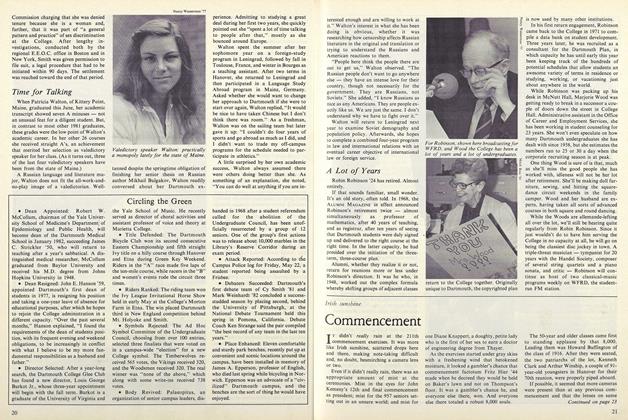

The College "play ground" in 1803, by George Ticknor, an 11-year-old sophomore.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSelf-Evident Truths

May 1976 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Feature

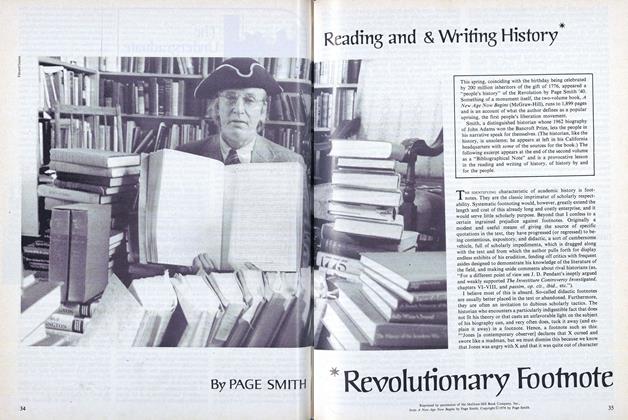

FeatureReading and Writing History and Revolutionary Footnote

May 1976 By PAGE SMITH -

Feature

FeatureWhen Dartmouth Had Its Own State (Almost)

May 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Feature

FeatureThanks to Daniel Oliver, A Gathering of Lovers

May 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

May 1976 By WALTER C. DODGE, CHARLES J. ZIMMERMAN -

Article

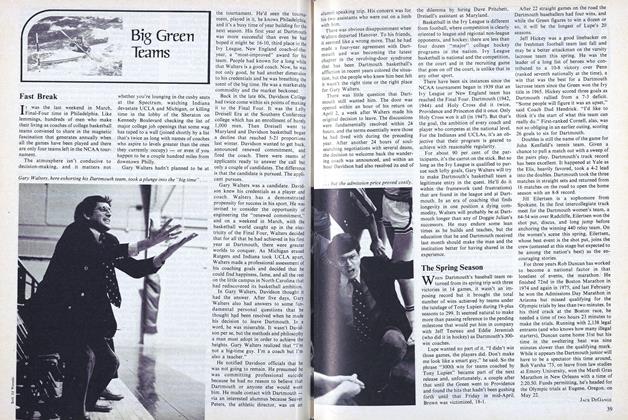

ArticleFast Break

May 1976

JAMES L. FARLEY '42

-

Article

ArticleADVOCATE OF PLENTY

November 1946 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureReunions, 1970 Style

JULY 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureThe Boom in Off-Campus Study

NOVEMBER 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

May 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

December 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleCommencement

June 1981 By James L. Farley '42