How ABSURD that a liberal arts college supports in its student body an anti-intellectual bias. Not a member of the derided intellectual minority myself, I have never been the target of that sort of discrimination. As a moderately observant face in the crowd, however, I've seen evidence of its influence. It seems to me that such a phenomenon ought to be recognized and resisted.

When I was in high school I heard a great deal about the academic pressure I could expect to find in college, particularly in the Ivy League. If that is actually the case, Dartmouth is hardly representative. Perhaps it doesn't want to be. Perhaps it only wants to compete athletically with Harvard, Princeton, and Yale. Perhaps it just can't make up its mind. It seems, though, that a subtle sense of academic inferiority, when compared with certain cultured southern sisters, may account for a not-so-subtle belligerence and for equating the loss of a football game with impotence.

An atmosphere of academic intensity is generated in at least one or two ways: either by high standards set by professors or by competition between students. Both, to a certain extent, exist at Dartmouth. Academic performance is not lacking, particularly if one uses such objective standards as grade-point averages - despite complaints of "grade inflation" - for measurement. Dartmouth students, if good at anything, are good at succeeding. Standards of achievement seem to be on a par with those set elsewhere.

Why then, if Dartmouth students are at least minimally intelligent, do they disdain intellectual interests and those who pursue them? Consider the definition of the adjective "intellectual": "Apprehensible or apprehended only by the intellect; nonmaterial, spiritual, ideal." Obviously, an enthusiasm for such concerns is not generated by intelligence alone. At Dartmouth, enthusiasms seem predominantly in favor of the material and practical. No intellectual pressure cooker here.

The pressures that do exist serve mostly to shape the individual into the not entirely accurate but certainly familiar Dartmouth stereotype: a good-natured, beer-guzzling, frat-hopping, road-tripping resident of a year-round semi-coeducational camp designed to ease the transition from high school to the real world. In four years here one earns a variety of merit badges in each of the major academic disciplines, concentrates in the one which seems easiest or most suited to a lucrative career, spends the minimum time necessary in the library and as much time as possible on the "Row," in the locker room, and on the prowl.

In a recent meeting of the faculty, Professor Roger Masters asserted that the Dartmouth student's "first concern was to get bombed, second to get laid, and third to play softball on the Green." A member of the Class of '7B corrected him by pointing out, in a letter to The Dartmouth, that his "primary concern" was "to get laid, not bombed."

The assumption that weekends are to be spent in any way but in study has been institutionalized. The library closes at 5 p.m. on Saturdays, opens at 2 p.m. on Sundays, and occasionally limits its hours for such special occasions as "big" weekends and bonfires. As a student, one associates with "Jocks" (not the article of clothing but the type of person who constantly wears one) by choice and with "Weenies" (serious students) by chance. This fall, for example, a rash of letters to The Dartmouth complained about the encroachments of "Weenyism" on the traditions of continuous weekend revelry, drunkenness, and midnight rowdiness. More recent letters have concentrated on such burning issues as the quality of entertainment at the Hanover Inn's Tavern and proposed cuts in the athletic budget. No one has mentioned the less serious matter of larger cuts in the budgets of the computer center and the library.

I mean to suggest by these observations that there is a pervasive spirit of conformity unsympathetic and occasionally antagonistic toward the intellectual and his or her peculiar enthusiasms. It is the odd student, in a student body of 4,000, who is stimulated and challenged by Baudelaire or Proust instead of beer-pong or pool. It is the relatively rare individual who stands up against the social mainstream to devote his energies primarily to intellectual interests.

Last month The Dartmouth carried a profile of a Fulbright scholarship winner, Robert Orton '76, who said he had become a virtual "recluse" partly because of his academic interests and partly because fraternities, rampant anti-intellectualism, "careerism," and superficial evaluation of peers cause severe isolation among Dartmouth students. "To be different," he said, "to fail to conform to an institution's 'middle-class respectability,' " is to be rejected.

The prevailing homogeneity may not entirely be the result of peer pressure. Perhaps it has something to do with admissions policy. Perhaps it is partly a response to economic pressures. In any event, the composition of the student body is notable for its lack of intellectual and political extremists. The attitudes of most seem extreme only in how "safe" and ordinary they are. There ought to be room for those professing passions both left and right, both above and below, the middle of the road, which at Dartmouth is oppressively narrow. A student body stands to gain, it seems to me, from differences. We need more misfits.

"... a good-natured, beer-guzzling, frat-hopping,road-tripping resident of a year-roundsemi-coeducational camp .... "

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA four-and -a-half-ounce magic totem pole

June 1976 By NORMAN MACLEAN -

Feature

FeatureTHE OLD ROMAN SPEAKS TO US STILL

June 1976 By DAVID SHRIBMAN -

Feature

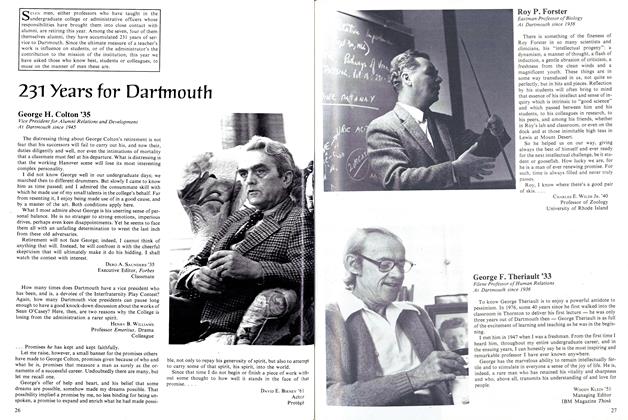

Feature231 Years for Dartmouth

June 1976 -

Feature

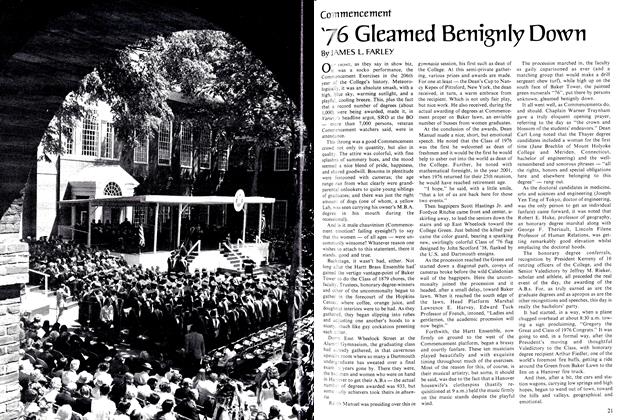

FeatureCommencement

June 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Article

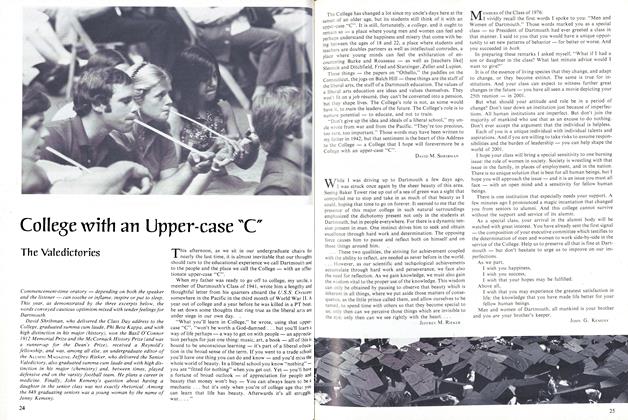

ArticleCollege with an Upper-case "C"

June 1976 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

June 1976 By DOUGLAS WISE

DAN NELSON '75

-

Article

ArticleA Dorm Is Not a Home

December 1975 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Article

ArticleThe American Forum

January 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Article

ArticleWarm Memories, Cold Pleasures

February 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Article

ArticleIn Defense of Prejudice

April 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Books

BooksTime and the Rivers

March 1979 By Dan Nelson '75 -

Feature

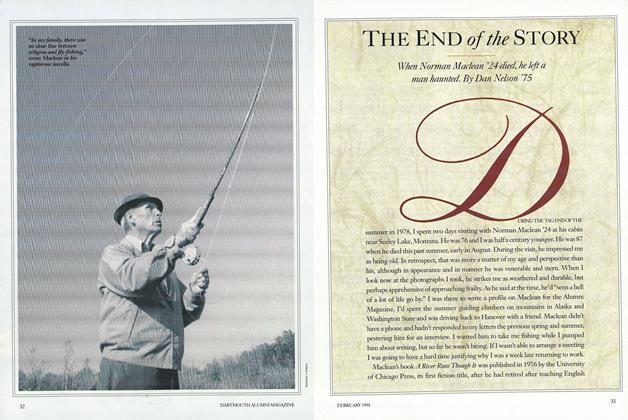

FeatureThe End of The Story

FEBRUARY 1991 By Dan Nelson '75

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE GRADUATES' CLUB OF HANOVER

June, 1910 -

Article

ArticleTabulation of Income and Expense for 1943-44

November 1944 -

Article

ArticleTeaching Wins Out

November 1961 -

Article

ArticleThe College

NOVEMBER 1967 -

Article

ArticleGLEE CLUB WINS ENTERTAINMENT AWARD

August 1942 By H. A. Dingwall '42 -

Article

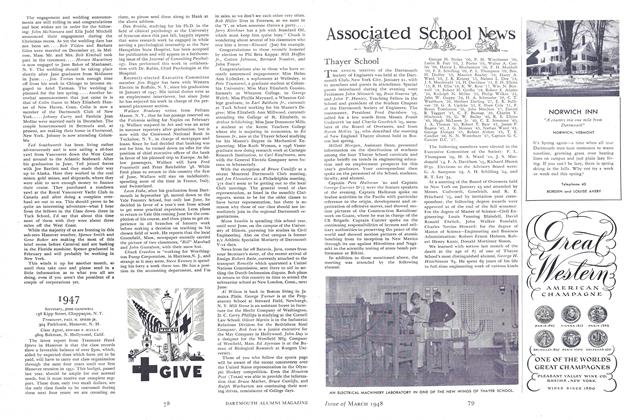

ArticleThayer School

March 1948 By William P. Kimball '29.