THERE'S a story about an old New Hampshire farmer, living near the state line, who discovered as the result of a geographic survey that he actually lived in Vermont. When asked if he was upset he replied, "Not really ... never did like those New Hampshire winters."

I live in Vermont and commute here to school in New Hampshire. Aside from the debatable question of which state actually has the hardest winters, I've come to realize after five years of winter residence that my favorite months are those of cold and snow between Thanksgiving and spring vacation.

My warmest memories are cold ones. When I was a freshman I had the good fortune to participate in Dartmouth's winter Outward Bound program. We spent the month of January hiking through the White Mountains and the College Grant on snowshoes or skis. During our first "expedition" we encountered a stretch of four days when the temperature ranged from a high of zero to a low of — 35.

We founded an exclusive nocturnal club, the Hot Sleepers. The individual who in the morning was found to have melted the deepest trough in the snow beneath his sleeping bag was proclaimed the champion of the previous night. Every morning and evening we had toe-checks. It was the honor of the hottest sleeper to revive the white and numbed toes of the not-so-hot sleepers on his bare stomach or under his arms. This stimulating ritual, a guaranteed social ice-breaker, was the most efficient method of overcoming the first stages of frost-bite and was often the beginning of warm and lasting bonds between its participants.

The elation of climbing out of a down sleeping bag, knocking from the inside walls and roof of the tent a growth of ice crystals formed by the condensation and freezing of the water vapor from respiration, while pulling on obstinately frozen boots and then running in circles for a few minutes to force circulation to the extremities before starting a fire or stove for breakfast, has no temperate equivalent. The delight of the palate over a breakfast of hot jello and grease bread (biscuits or bread crusts soaked and fried in an inch of spitting hot bacon fat) cannot be matched by the more sedentary intake of a doughnut and coffee at Lou's on Main Street.

I enjoy winter adventures immeasurably more than the relative ease of summer excursions. The woods and mountains are almost exclusively my own. Even in the busy Pemigewasset Wilderness, usually swarming with pilgrims from Connecticut, invalids seeking a cure of Bostonitus, and popular locale for New York fashion shows and conventions, one can find solitude a mile up the trail. More importantly, the successful adaptation to and skill aquired in traveling through an environment of extremes with complete self-sufficiency give rise to a sense of confidence, satisfaction, and accomplishment rarely experienced elsewhere.

The mundane satisfactions of winter chores are also worth their weight in cord wood. There is something about splitting a maple log with the first swing of the axe, snapping your wrists and giving the handle a little twist at the last minute and then hearing the cracking of the grain, that can keep a person who has found the right "touch" working at a wood pile on a February afternoon until it gets too dark to see. The hard work has a solid value. "That wood will warm you twice," my neighbor told me, "once with the splitting and again with the burning."

Sometimes the fun is pure and simple, like cross-country skiing on a cold day with green wax in a good track when you've finally found the effortless stride that flows over miles so fast you hope the snow never melts and you never have to walk again. Then you forget the week before when you chose red klister and your friend chose purple and he left you a mile behind, scraping snow, pine needles, and wax off your sticky skis. This reminds me of the smell of pine tar being torched into hickory skis, an odor which certainly ranks as high as that of wet woolen underwear, socks, and mittens hanging to dry over a wood stove.

You couldn't pay me enough to live and work in some part of the country without winter and the open space in which to enjoy it. The more winter and the more space the better. My former roommate somehow landed a job working on the pipeline in Alaska. He wrote me a letter gloating about a temperature of — 45 - and that was before winter had even begun. Sometimes I feel like dropping everything, including graduation in June, to join him.

What keeps me here is a disquieting sense of "responsibility," the scarcity of jobs there, and the optimistically frigid forcasts in the Farmer's Almanac for this my final winter in New England. (February 6-8 looks good: "sunny & fair but very cold" and February 9-12 even better: "snows some to midweek; near record cold.") I find myself daydreaming about the Yukon, which I've never seen, while reading the inspired ballads of Robert Service, the worst poet ever to write in the English language. The immortal voices of Sam McGee, Blasphemous Bill, and Dan McGrew have more than once distracted me from study.

For most of us winter excursions are hardly more than a game afforded by luxury, in the end temporary immersions into an environment we can always choose to leave. The game, however, can be played for high stakes and the very real pleasure in it can be consuming. It can function as an analogy for the values of more general and common experience.

I enjoy this frivolity largely because it is difficult. A climb or hike in winter extremes, preferably of several days duration, can be an antidote to the numbing effects of ordinary comfort. When comforts are hard-won, when little that one does is superfluous, one can see the outlines of values in sharper relief.

Two scenes come to mind as examples of the real pleasure I find in winter. One was the spectacle of a sunset seen from a meadow outside Hanover while skiing to Harris Cabin. The other was a Sunday morning on top of Mt. Moosilauke, trying to walk in the face of a furious wind. Both elicited a certain response, perhaps religious, perhaps aesthetic, but characterized best by a pervasive sense of joy and excitement, not only in the sensous experience, but also in living altogether. This, too, is part of an education.

"... grease bread andhot jello delight..."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePursuing Sleep

February 1976 By B.K. THORNE, NANCY DECATO -

Feature

Feature'Save the zebra! Save the zebra!'

February 1976 By GREGORY SCHWARZ -

Feature

Feature'... A whole pool of frustration, anger, resentment...'

February 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Feature

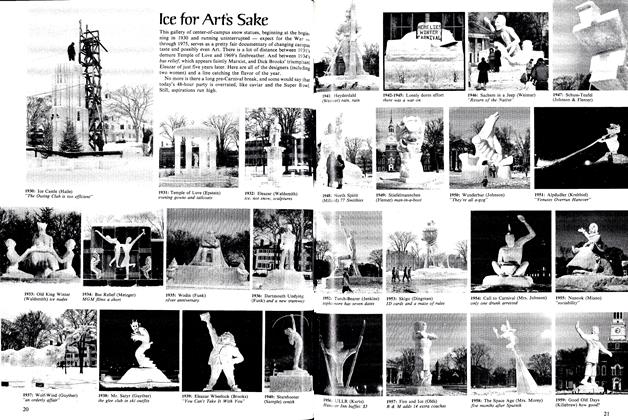

FeatureIce for Arťs Sake

February 1976 -

Article

ArticleWinter Games

February 1976 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

February 1976 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE

DAN NELSON '75

-

Article

ArticleA Dorm Is Not a Home

December 1975 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Article

ArticleThe American Forum

January 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Article

ArticleIn Defense of Prejudice

April 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Feature

FeatureThanks to Daniel Oliver, A Gathering of Lovers

May 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Books

BooksTime and the Rivers

March 1979 By Dan Nelson '75 -

Feature

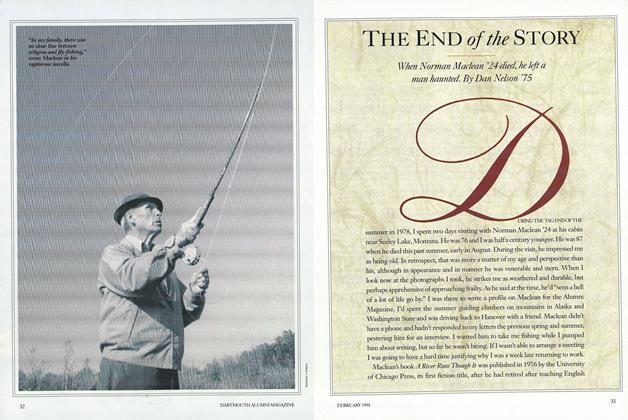

FeatureThe End of The Story

FEBRUARY 1991 By Dan Nelson '75

Article

-

Article

ArticleNOTES

January, 1925 -

Article

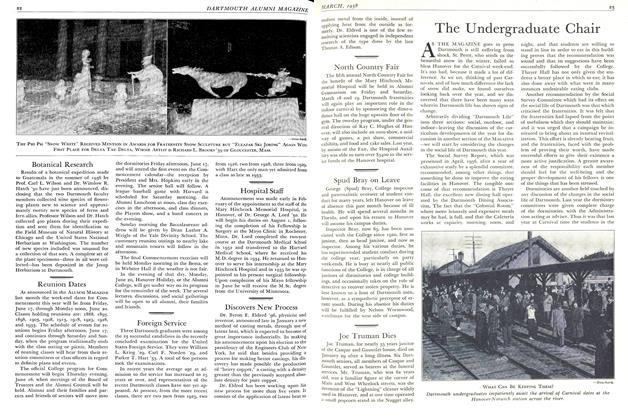

ArticleDiscovers New Process

March 1938 -

Article

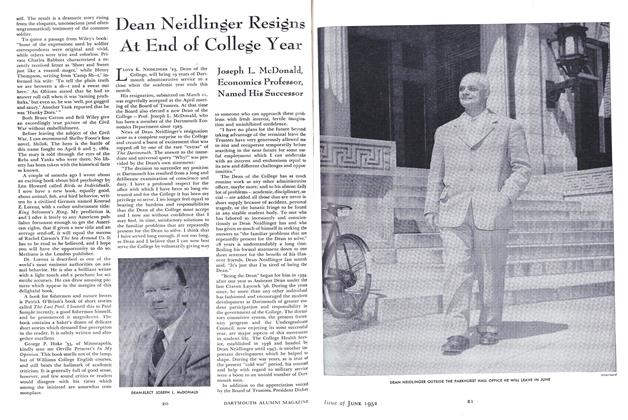

ArticleDean Neidlinger Resigns At End of College Year

June 1952 -

Article

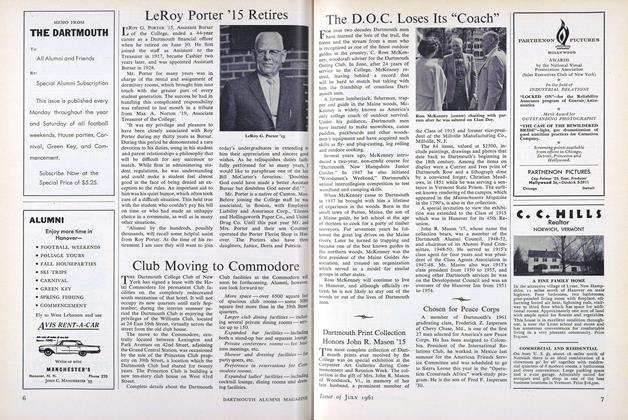

ArticleThe D.O.C. Loses Its "Coach"

July 1961 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S FLOOD WORK SALUTED IN SO. CAROLINA

JANUARY, 1928 By "Katherine Dozier -

Article

ArticleAbout Twenty-Five Years Ago

November 1932 By Hap Hinman'10