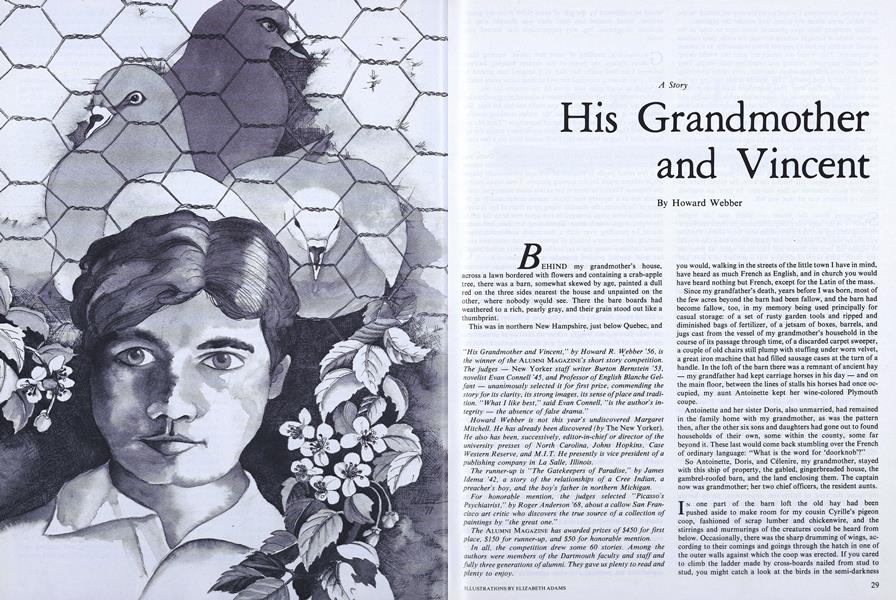

BEHIND my grandmother’s house, across a lawn bordered with flowers and containing a crab-apple tree, there was a barn, somewhat skewed by age, painted a dull red on the three sides nearest the house and unpainted on the other, where nobody would see. There the bare boards had weathered to a rich, pearly gray, and their grain stood out like a thumbprint.

This was in northern New Hampshire, just below Quebec, and you would, walking in the streets of the little town I have in mind, have heard as much French as English, and in church you would have heard nothing but French, except for the Latin of the mass.

Since my grandfather’s death, years before I was born, most of the few acres beyond the barn had been fallow, and the barn had become fallow, too, in my memory being used principally for casual storage: of a set of rusty garden tools and ripped and diminished bags of fertilizer, of a jetsam of boxes, barrels, and jugs cast from the vessel of my grandmother’s household in the course of its passage through time, of a discarded carpet sweeper, a couple of old chairs still plump with stuffing under worn velvet, a great iron machine that had filled sausage cases at the turn of a handle. In the loft of the barn there was a remnant of ancient hay my grandfather had kept carriage horses in his day and on the main floor, between the lines of stalls his horses had once oc- cupied, my aunt Antoinette kept her wine-colored Plymouth coupe.

Antoinette and her sister Doris, also unmarried, had remained in the family home with my grandmother, as was the pattern then, after the other six sons and daughters had gone out to found households of their own, some within the county, some far beyond it. These last would come back stumbling over the French of ordinary language: “What is the word for ‘doorknob’?”

So Antoinette, Doris, and Celenire, my grandmother, stayed with this ship of property, the gabled, gingerbreaded house, the gambrel-roofed barn, and the land enclosing them. The captain now was grandmother; her two chief officers, the resident aunts.

In one part of the barn loft the old hay had been pushed aside to make room for my cousin Cyrille’s pigeon coop, fashioned of scrap lumber and chickenwire, and the stirrings and murmurings of the creatures could be heard from below. Occasionally, there was the sharp drumming of wings, ac- cording to their comings and goings through the hatch in one of the outer walls against which the coop was erected. If you cared to climb the ladder made by cross-boards nailed from stud to stud, you might catch a look at the birds in the semi-darkness there above. Sometimes I would go all the way up, crouch on the hay there, arms about my knees, and ponder the pigeons.

Their compact little eyes glistened from time to time in the narrow shafts of sunlight coming through the walls, their curious splayed feet they picked up and put down incessantly, as if uneasy or impatient. They would not return my gaze but would swivel their heads nervously, settling and resettling their wings. They cooed and were attentive, one to the other, only rarely quarreling but then bitterly and briefly. They bent to drink, sucking up the water in an unbirdlike way. They assembled their nests without any instinct for architecture; all were catastrophes of design, and some collapsed from the weight of the very inhabitants who had made them. The squabs, bare, ugly little creatures, they fed in- delicately a fluid made in their own throats.

Once I saw an ancient bird drop from his perch to the litter beneath, coming to rest on his back, his legs extended above him. The life had left him, and what remained was the effigy of a pigeon, so stiff and silent as obviously not to be real, as if death had been a taxidermist, perversely stuffing this animal with his own guts. Later, Cyrille recovered the dead pigeon and threw him onto the compost pile behind the barn. He rotted there, an object of great attention to flies and ants. In time, an ungainly bunch of feathers was all that was left.

Stretching from the house which was on higher land to the barn was a long clothesline, its ropes bending in the most delicate arc, like tram cables seen from above. The line was run on reels, full circle, so that the garments hung there could be wound out into the breeze and then back again, all from the rear porch. Each piece of clothing was a pennant of a sort, and Antoinette was unwilling to allow certain of these flags to be read by whoever might observe them. She carefully pinned every bra, panty, slip, "and girdle beneath an innocent sheet or towel.

Uncle Pierre, Cyrille’s father and the husband of one of those sisters who had left the household, spoke about it once as he was hoeing the garden patch the family allowed him to keep on the property, the day being very hot and the sweat running from his brow and the part of his chest that showed above his undershirt, flowing in little channels as if he had been punctured at certain points and there were water inside. “What do you suppose she’s trying to show? Is she trying to show that she doesn’t wear any pants? Does she mean she’s got no bottom like the rest of us?” He laughed to himself, but not a great deal.

But I liked to think of the clothesline as the safe cord of communication between the house and barn, a kind of rope ladder to the crow’s nest of the loft, over which food and drink, and even persons, might be passed should danger threaten. I could not have said what kind of danger, but I observed with interest that the line hung far above the ground, that it could be reached without leaving the house counting the porch as part of the house and that it was in theory possible for whoever was passed along it by basket or breeches buoy to hoist himself through the loft door just above the end of the line at a hook on the barn.

In my imagination I took that voyage or its reverse many times. If I happened to be in the barn, I conjured up improbable invasions or disasters that made the use of this means of escape to the house the kind of bittersweet opportunity, partly having danger in it but partly safety, of which adventure is compounded. I turned myself inside out, in my mind being more kinesthetic than the boy who was merely trotting along beneath the line. I pitched and rolled in mental suspensions as if I had really been hanging under that rope, making out of nothing the hands or jaws that clutched beneath me, squinting my eyes and compressing my breath, shuddering for the length of the passage. I was exultant as, the gantlet passed, I reached at last the safe deck of the porch.

I turned myself right side out again. In the house my arrival would be celebrated by the gift of some tidbit from my grand- mother, bread toasted less hard than was thought wise for children, doughnuts, big, airy peppermints that burned your teeth.

Grandmama, smelling of yeast and spices, wearing black shoes always, the hems of her dresses hanging halfway between knee and ankle, her hair in a tangled bun pinned by thick, gray skewers, exercised her will in these latter years mostly by breaking small rules laid down by my mother for me.

Afterwards, by way of recompense, I allowed my grandmother to take me into her lap, though I was really too big for that. She rocked me in the old wicker chair, the withes creaking comfortably as the chair moved, and hummed sometimes “Take Me out to the Ball Game.” Later, Doris might accompany me on the up- right while I sang in the soprano I still would have for a few more years.

Masculine of feature, having a great, jutting jaw, Doris was very modest of public manner. She gave piano and violin lessons to a few select pupils to support herself and occasionally played the Wurlitzer organ for the moving pictures. I was taken once to the Princess Theatre to observe her at this latter enterprise, and it struck me as a mystery that Doris, seated conspicuously at the front of the theater, the manuals rising Up in front of her in steps, the multicolored stops arranged in row upon row from far left to far right, a gooseneck lamp illuminating her face and arms, should be presiding over such a thoroughly visible exhibition, creating the proximate sounds of adventures and calamities alien to the ordinary being she was, her hair discreetly rolled behind her head, her hat perched genteelly at the crown of it.

About everything Doris did there was a tentativeness, a certain expectation of rebuff. Even within the family she, though cheerful by temperament, sometimes inhabited corners, ventured few opinions, inconspicuously took up drudgeries, was last to be greeted in arrivals, and in good-byes might be overlooked.

But Doris had time for all my games, and if there was a circus at Horne Field, Ringling Bros, or Barnum & Bailey, banners fly- ing brightly above the trees and through them the glorious bulk of the tents showing, she bought tickets for the two of us and took me to see it: Poodles Hanneford and family bareback, Arthur Concello and his beautiful wife Rosa on the flying trapeze.

Or I might be allowed to watch as Antoinette sewed, one foot on the treadle, fingers perilously intermeshing with the lightning strike of the needle, sharp white teeth slashing the thread when the cycle was done. Or as she braided remnants of cloth and stitched them into a tight vortex that, I did not understand how, would lie evenly upon the floor once it was set down as a finished rug. Antoinette also let me play in the clothes closet upstairs in her bedroom. Behind the garments, there was what I, always scouting a mystery, thought was a hidden door, giving upon the adjacent room. Or she took me out for rides in the rumble seat of the Plymouth, she beautiful and beautifully attired in the cockpit, racing the motor, calling out to acquaintances as she passed, I silently ecstatic in that separate balloon dragged about after this enchanting vehicle.

Even ignored, I enjoyed my grandmother’s house. I worked the serving door between the kitchen and dining room, intrigued by the act of opening up the wall. I watched the porcelain clock, whose works were visible behind a little glass door, and waited for it to chime. I explored the thousand rooms of the cellar, where the huge furnace squatted, like some Eastern god, its many arms raised about it, where coal was mounded up, wood reclined neatly in rows, jars of preserves collected dust.

When finally I left, walking the scant mile up the road to my home, it was to return to what seemed a dishearteningly ordinary world, to a smaller and plainer dwelling place, to a mother occupied with the mechanics of what seemed to me a thoroughly obvious household, to my chemist father who came and went always at the same hours.

On Sunday, after church, after the roast beef or lamb, after the harlequin ice cream, it was my father’s habit to take us for a drive. He at the wheel of the Terraplane, I and my mother beside him, we went first to my grandmother’s house, pausing there with the rear doors of the car open. My grand- mother and aunts would have been waiting in the hall, and as we appeared they came down to take their places behind, Doris offering to sit in the middle, Antoinette, wearing something pale that would have to be protected from a boy’s shoes and hands, letting her. My grandmother always wore a black cloth coat, a purple dress, and a black hat with a sprig of artificial violets on it. She would have one of those peppermints hidden in her hand for me.

We drove through the nearby villages, coming to a halt at one or another scenic spot, a pond or a birch grove, a mountain overlook or some swift stream. We would have brought picnic baskets, and these we unloaded and placed in cool shadow. Then we walked, or “hiked” we said, slowly by the shore, among the trees, along the bluff, I running ahead, surprising rabbits, climbing rocks or hoisting myself on branches. In time, we turned about, and, back where the car was, my elders would spread robes or unfold canvas stools and seat themselves.

If we had settled ourselves by a stream, my occupation might be to gather enough of the rounded stones of the bed to make myself an island, lifting and dragging, my shoes off and pants rolled up, the cold mountain water bubbling about my legs. When my work was complete, I would sit upon my island, idly making a plane of my hand in the passing water, casting pebbles at the water bugs in the shallows, observing my family. My father, hav- ing undone his collar, was lighting his pipe, or whittling a stick, or telling a story. My mother was rummaging through her open darning basket or reading a magazine or gossiping with Doris. Antoinette was sketching in charcoal or gathering wild flowers, or, if there were others present besides ourselves, striking up animated conversations with them. And my grandmother.

My grandmother with her hair now never carefully combed, her plain, aged face, her venous hands, folding and refolding the fabric they were near into neat pleats, as if so accustomed to activity that they could not now cease it, polishing her eyeglasses, smoothing the blanket. I remembered, sitting on my island, the lore of our family: That my grandmother had long, long ago been very ill, so that the doctors had told my grandfather that she would not recover, but she did recover, by force of will, because she heard her children crying for her in the other parts of her house; that my grandmother had nursed Antoinette out of a paralysis by bathing her in water as hot as flesh could stand and rubbing her limbs with oil of wintergreen; that in the great influenza epidemic my grandmother had taken into her house during their fevers Mme. Morrisette and her two children, then Mme. Dumont and Michel, Joseph, and Paul of her eight, then Ellie Turner, a queer old English woman who lived alone, believed in spirits, bickered with any child who crossed her path, and was suspected of spite by all her neighbors. In my mind I rehearsed these legends in the words in which they had been passed on to me, feeling in them the solemn weight of family history.

Once I remember I went over to my grandmother in the soften- ing light of the afternoon’s end and put my head under her hand. As the sun moved lower the aspect of the land moved, and I thought I could see it changing, advancing, becoming all the lovelier. The expanding beauty of the land came together in my mind with the progress of our family, and I felt as if we also were the flower and the fruit of the country. “Grandmama,” I said, “est-que c’est done beau.”

“Vraiment, Vincent,” she said to me, amused but touched, too. “C’est beau comme toi-meme.”

We drove homeward at dusk, I drowsy, watching the shadow- trees and shadow-meadows revolving past the car windows, stir- ring as we reached the house of my grandmother and she and my aunts disembarked. Always as she left she said, “Thank you a thousand times.”

It was in early spring when I came in one day to find my mother seated at our kitchen table with a paring knife, extracting green beans from a bag and clipping them for cooking. I barely gave her my attention as I approached but then halted as my eyes remained on her face, altogether a different face this morning, displaced from its customary mold by some influence I did not understand. It was as if her body were going about its usual activities under quite another head, and I thought of the game of matching cards upon which were represented dis- membered figures a policeman, a sailor, a clown each to be joined together, of the preposterous exchanges of parts I would sometimes engineer.

My mother did not look at me. I stood by her, and as I stood she began to cry, her tears falling upon the moving knife and the vegetable piles. In the back of my mind there was a small impulse of laughter, but I hardly felt it before it was suppressed by a much stronger sense of alarm. I did not ask her what was the matter; I was afraid to know. I waited uncomfortably, and at last she said, her hands still working, “It’s Grandmaman, Vincent.”

My alarm focused on the person of my grandmother, and frames of disaster spun through my mind: an automobile veering toward her, its driver asleep or unheeding, an explosion in the furnace and she in her wicker chair on the floor above, her foot upon a loose board at the top of the stairs. ‘Grandmaman’s sick.”

Infection, the putrefaction coursing along the channels of the limbs to the organs, to the brain; raging fever, cramps knotting the muscles, the teeth grinding, the eyes open but unseeing.

“Her heart.” Inside my chest my own heart beat loudly and my pulse rang in my ears as the echo of it.

“Doris called last night. I went down while you were asleep. This morning Grandmaman’s the same. She doesn’t move.”

My lungs were full of breath for speaking, but with all that air, I said only, “I’m sorry.” The words came out loud, aspirate.

“Yes, yes, I know you are,” my mother said. She rubbed her eyes with the backs of her hands, as if to dam them up, and took a brave posture, her back straight, a careful expression of composure on her face, but that was all a sham, for tike tears came still.

I backed-away, slowly at first, as if I might be called to return, then more rapidly, going outdoors again, relieved to have the house behind me. The sun shone. The fields were full of rivulets of melted snow, and these glistened in the brown grass, made just hearable noises, which finely laced the air with the sound of tiny cymbals. Somewhere a dog barked eagerly. I.made my way to an enormous boulder some distance from our hpuse, a mountain in itself, cast carelessly away by the glacier on which it doubtless had ridden. I climbed to the top of it. A depression in the surface there made a kind of mineral armchair, in which I seated myself.

I tried to imagine a heart, the heart of my grandmother, veined, darkened perhaps with age, glazed or inflamed with infirmity. I imagined the heart beating, not mechanical, not driven by any exterior force, but moving with the free impulse of living things, with the secret energy of otters pushing themselves lithely through pools, of the chick attacking the walls of its egg. I imagined the heart stopping, and the whole beautiful, refined body poised on the edge of being, waiting, waiting, for the returning pulse, and, when it did not come, tipping into blackness. Though the sun was warm upon my back and before me a season was opening and the world prospered, I shivered.

I got up and let myself to the ground. In the distance my father’s car was coming to a halt in front of our house. As he left it he saw me and stood, one hand upon the open door, watching me. He did not wave or call out, nor did I make any sign to him, though he was not usually home at this hour. My mother came out of the house, and he helped her into the car. They drove away, toward my grandmother’s.

I set out after them, running so as not to lose sight of them. When I reached my grandmother’s house, the car was empty, and they had disappeared. I scanned the windows, but nothing could be seen. One was open upstairs, and curtains blew over the sill. I thought of the noise the door chime would make should I ring it. I wondered what I would say when the ring was answered. Then the door opened, and Doris came out.

She bent over me. “Your grandmother’s sick, Vincent,” she said.

“I know,” I said. “Your father and mother have come.” “I followed them,” I said. “I can’t let you in. We have to be very quiet in there.” “Is she going to get better?” I asked. “Yes,” Doris said. Then she reconsidered. “No,” she said, in another tone. “I don’t think she will.” She looked at me a moment. “Go home, Vincent,” she said, putting her hands on my shoulders and turning me in that direction. “It will be over soon enough.” I did as she told me.

That evening, as I was getting ready to go to bed, my uncle Pierre arrived. I heard his knock and went far enough down the stairs to see. He was standing near the door, one hand awkwardly in a pocket.

My mother said two or three words denoting inquiry. Pierre, as if he were ashamed, said, “Yes. Just a few minutes ago.” My mother groaned.

I thought of the flower garden my mother had tried to grow some seasons before, choosing, as someone without an intuition of the best interests of plants, an inauspicious site, full of stones, in the path of gullies during rain, in dry weather baked to crack- ing by the sun, subject to dogs and children. In my mind I saw her bent over the poor sprigs that endured to leaf, chopping energetically at them with a trowel, confident that her relentless cultivation would bring them to flower, her graying hair drawn back along the sides of her head, dirt caked about her wedding ring, her face, a little plump, full of fervor. She wanted flowers, but she got none.

One day she said to my father, “I guess it’s hopeless, Al.” He, his features soft, a large and amiable man, comforted her. “We’ll try again next year. Or I’ll buy you some.” “It won’t be the same,” she said.

I thought of this as I saw those two together after Pierre had left. They stood, arms about one another, a single pillar in the center of the room, closing the world out, closing me out.

I went quietly to my bed, to dream disturbing dreams, disorderly snatches of tales, full of contradictions, none leading to the next. When I awoke in the morning, the dreams did not dis- solve as my ordinary dreams did under the light admitted by my eyes but continued, as musings, sudden images floating over the field of reality and hiding it, brief, feverish visions. Looking back, I cannot tell dream from reality.

I cannot tell whether, swinging our legs, my friends and I did sit on a stone wall across the road from my grandmother’s house, keeping account of the activities there, the delivery of flowers, the entry and exit of neighbors, the arrival and departure of the undertaker in his black panel truck embellished with a circlet of silver leaves. At the door of the house there is a spray of flowers tied with a broad black ribbon. My mother appears, dressed in black, and she signals me. I go over to her. Earnestly she says, “You must tell your friends to be quiet.” I return to them and deliver her message. “Why?” says Alan McKay. “Because my grandmother’s dead,” I say. He thinks a moment. “You don’t seem to be sad about it,” he says.

I am alone on the porch of the house. I decide to go in. In the parlor, to the right of the hall, I see the undertaker, thin, sallow, pious. His coat is hung over a doorknob, and he has rolled up his shirtsleeves, exposing arms like chickens’ legs. In his hand he has a large, pink comb, and he is combing my grandmother’s hair. She lies in the coffin, her eyeglasses in place, her hands folded, wearing the purple dress, and he is ordering the tangled moss of her old head, standing back now and again to observe the effect. At length, slipping the comb into an interior pocket, he energetically pinches the corners of her mouth, to improve the expression.

I am still in the hall. The undertaker has said, “She’s ready now.” A throng of aunts and uncles, adult cousins, and im- mediate neighbors begins to move through the hall toward the parlor. My mother brushes past me, and my father, but they do not speak to me. No one speaks to me. When those who have been waiting reach the parlor entrance, they all draw back a little, looking over one another’s shoulders at the coffin within. A certain commotion occurs in the direction of Antoinette, who puts her hands to her eyes and begins to sob. “I can’t go in,” she says. Uncle Pierre is nearby, and she leans into him, hiding her face on his chest. Her shoulders rise and fall, but the sound is muffled by Pierre’s coat. Then the volume of the sound begins to escape from the corners of her mouth and, having made a channel there, widens it and floods the hall. Doris comes up. “ ’Toihette, don’t cry,” she says. “Come, we’ll go in together.”

I am by chance alone with the body of my grandmother, and I see her hand move, two fingers rise. I study those fingers until my eyes swim. I do not dare to approach. I watch for the movement of breath, for a trembling of lids. I think I see them, I think I do not.

66 A /Vincent, Vincent,” my mother is calling. “Do you hear me, Vincent?”

“Here I am,” I say, being in my room in our house.

“It’s time to get ready.”

My mother is short with me as I dress for the funeral, and somehow I am grateful for that. She sends me to shine my shoes once again and takes a rough hand in the tucking in of my shirt. She cuffs me along to the car because I am laggard.

In the church: “But some man will say, How are the dead raised up? and with what body do they come?”

At the cemetery: the obscure scrabble of the handful of dirt tossed after the casket sounds to me like thunder.

Then we are back inside my grandmother’s house. The parlor is empty now not only of the casket but of the heavy purple curtains and the candles, the folding chairs and the gold crucifix on a stand. Doris has gone into the kitchen to make coffee. Other relatives arrive and sit conversing in the living room. I am by my mother, and I am sure I really was there I stood by my mother and my father, and Antoinette said, “It’s like the time Doris and I were lost. Do you remember? At Christmas? We came back long after dark.” My mother said, “And what will you do now, you and Doris. Will you sell the house?”

Antoinette began to reply, but I left the house and went outside again. I wandered aimlessly in the yard, picking up a stone and throwing it, watching a beetle make its way through a clump of grass. Then I opened the barn door and entered. I blinked in the darkness. Above I could hear the pigeons. I climbed the ladder into the loft.

The birds were rustling on their perches. One was preening another’s feathers. A traveler returned through the hatch, occupying himself then at the feed tray, taking up the grain there, with a seasoning of sand from a nearby dish. I began to consider the change of grain not into a plant after its own kind but into the flesh of a bird. I thought of the grain growing in the ground that would feed the pigeons, and I thought of the earth and water coming together to form the grain, which was not earth and water but was made of earth and water, and I thought of the grain, blooded, feathered, beaked, flying over the earth from which it came, flying very high above it.

A handsome old bird separated himself from his fellows, approached the hatch, and paused there, the light coming in over him. In a moment he thrust himself outward, beat his wings, and was gone. I had a feeling of parting.

Then Doris appeared on the ladder. She was dressed still in her funeral clothes, and the oddness of her being in the barn occurred to me.

“What are you doing, Vincent?” she asked me.

“Feeding the pigeons,” I said, which I was not doing, and would not have done, for the pigeons had their full tray from my cousin.

“Will you come down?” she said to me.

I went down.

She put her arm over my shoulder as we walked to the door of the barn. I noticed there were tears in my eyes, and she waited with me while I cried. It was easy to mourn, I discovered. One did not have to struggle for breath or make noise. One did not have to move one’s shoulders. One could weep with no more arrangement than breathing itself takes. It was not even necessary to be sad.

“Never mind, Vincent,” Doris said. “I’ll be your grandmother now.”

“His Grandmother and Vincent,” by Howard R. Webber '56, is the winner of the Alumni Magazine's short story competition.The judges New Yorker staff writer Burton Bernstein ’53, novelist Evan Connell ’45, and Professor of English Blanche Gelfant unanimously selected it for first prize, commending the story for its clarity, its strong images, its sense of place and tradition. ‘‘What I like best,” said Evan Connell, ‘‘is the author’s integrity the absence of false drama.”Howard Webber is not this year’s undiscovered MargaretMitchell. He has already been discovered (by The New Yorker). He also has been, successively, editor-in-chief or director of the university presses of North Carolina, Johns Hopkins, CaseWestern Reserve, and M.I.T. He presently is vice president of a publishing company in La Salle, Illinois.The runner-up is "The Gatekeepers of Paradise,” by James Idema ’42, a story of the relationships of a Cree Indian, a preacher’s boy, and the boy’s father in northern Michigan.For honorable mention, the judges selected “Picasso’sPsychiatrist,” by Roger Anderson ’6B, about a callow San Francisco art critic who discovers the true source of a collection of paintings by “the great one.”The Alumni Magazine has awarded prizes of $450 for firstplace, $l5O for runner-up, and $5O for honorable mention.In all, the competition drew some 60 stories. Among the authors were members of the Dartmouth faculty and staff and fully three generations of alumni. They gave us plenty to read and plenty to enjoy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Well-Tempered Synclavier

December | January 1977 By Woody Rothe -

Feature

FeatureReflections on an $8-million post office The Hopkins Revolution

December | January 1977 By Henry B. Williams -

Article

ArticleResident Rotiferologist

December | January 1977 By S.G. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

December | January 1977 By THOMAS G. JACKSON -

Sports

SportsThe Coach Departs

December | January 1977 By Brad Hills ’65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

December | January 1977 By STEPHEN D. SEVERSON

Features

-

Feature

FeatureArt Collection Enriched

January 1961 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRichard Owen '45

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureOVER-RATED

Nov/Dec 2000 -

Feature

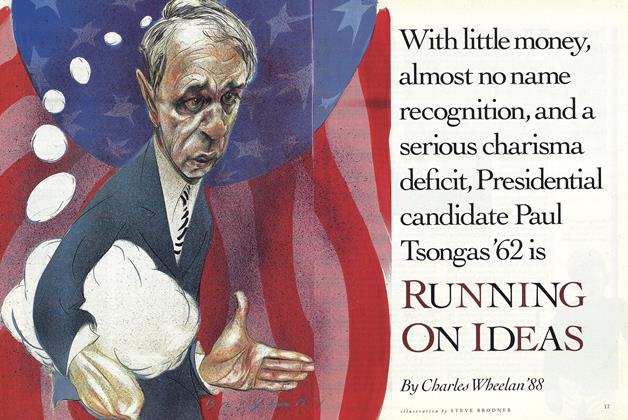

FeatureRUNNING ON IDEAS

OCTOBER 1991 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

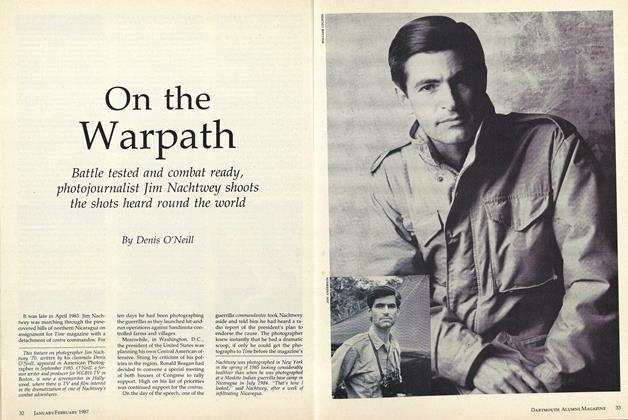

FeatureOn the Warpath

JANUARY/FEBRUARY • 1987 By Denis O'Neill -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTeacher in the Dorm Room

MARCH 1989 By Paul Susca '80