These conditions further require thatundue strain upon players and coaches beeliminated and that they be permitted toenjoy the game as participants in a form ofrecreational competition rather than asprofessional performers in public spectacles.

Ivy League Agreement of 1954

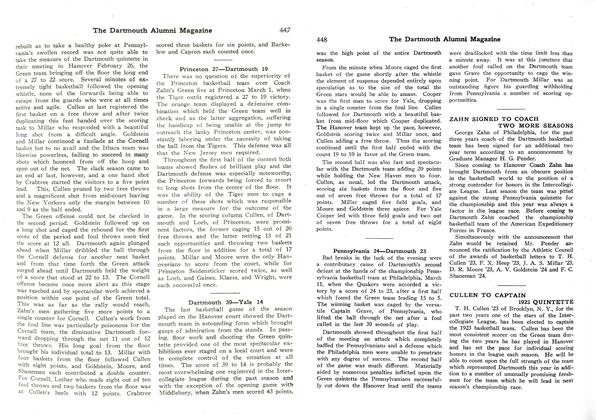

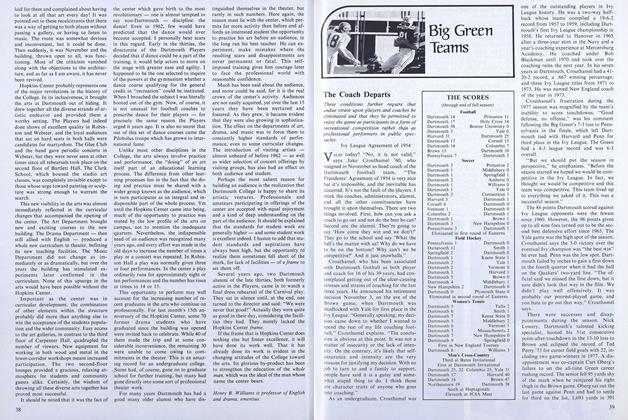

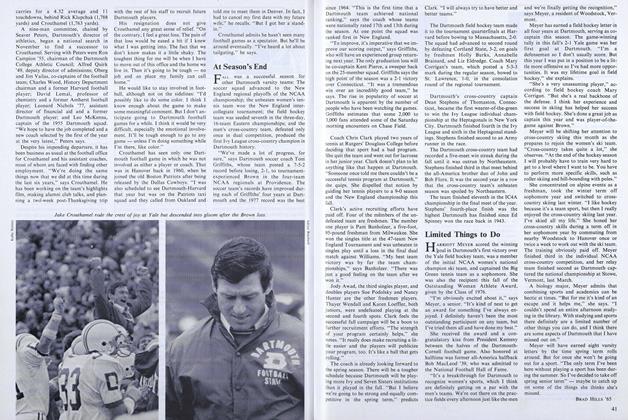

Valid today? “No, it is not valid,” says Jake Crouthamel ’60, who resigned in November as head coach of the Dartmouth football team. “The Presidents’ Agreement of 1954 is very nice but it’s impossible, and the inevitable has occurred. It’s not the fault of the players. I think the coaches, administrators, alumni, and all the other constituencies have brought it upon themselves. There are two things involved. First, how can.you ask a coach to go out and not do the best he can? Second are the alumni. They’re going to say ‘How come they win and we don-'t?’ They go to the school and say ‘What the hell’s the matter with us? Why do we have to be on the bottom? Why can’t we be competitive?’ And it just snowballs.”

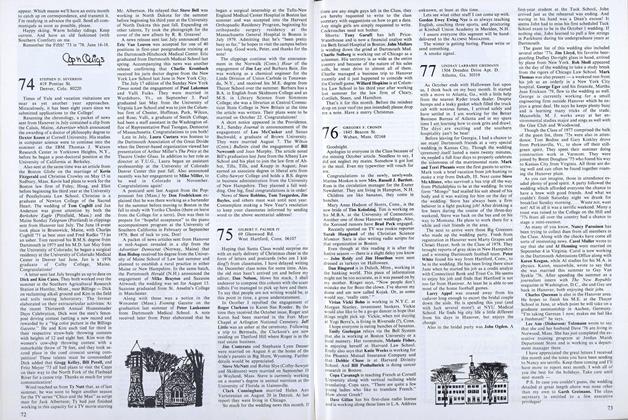

Crouthamel, who has been associated with Dartmouth football as both player and coach for 16 of his 39 years, had con- templated getting out of the ulcer-causing stresses and strains of coaching for the last three years. He announced his retirement decision November 3, on the eve of the Brown game, when Dartmouth was deadlocked with Yale for first place in the Ivy League. “Generally speaking, my deci- sion came down to whether I wanted to spend the rest of my life coaching foot- ball,” Crouthamel explains. “The conclu- sion is obvious at this point. It was not a matter of insecurity or the lack of inten- sity. On the contrary, it’s likely that self- assurance and intensity are the very reasons for justifying my decision. With no job to turn to and a family to support, people have said it is a gutsy and some- what stupid thing to do. I think those are character traits of anyone who goes into coaching.”

As an undergraduate, Crouthamel was one of the outstanding players in Ivy League history. He was a two-way half- back whose teams compiled a 19-6-2 record from 1957 to 1959, including Dart- mouth’s first Ivy League championship in 1958. He returned to Hanover in 1965 after a three-year stint in the Navy and a year’s coaching experience at Mercersburg Academy. He coached under Bob Blackman until 1970 and took over the coaching reins the next year. In his seven years at Dartmouth, Crouthamel had a 41- 20-2 record, a .667 winning percentage, and three Ivy League titles from 1971 to 1973. He was named New England coach of the year in 1973.

Crouthamel’s frustration during the 1977 season was magnified by the team’s inability to score touchdowns. “Good defense, no offense,” was his comment following the Big Green’s 7-3 loss to Penn- sylvania in the finale, which left Dart- mouth tied with Harvard and Penn for third place in the Ivy League. The Green had a 4-3 league record and was 6-3 overall.

“But we should put the season in perspective,” he emphasizes. “Before the season started we hoped we would be com- petitive in the Ivy League. In fact, we thought we would be competitive and this team was competitive. This team lived up to everything we asked of it. This was a successful season.”

The 86 points Dartmouth scored against Ivy League opponents were the fewest since 1960. However, the 96 points given up to all nine foes turned out to be the sec- ond best defensive effort since 1965. The Yale game was the high spot of the season. Crouthamel says the 3-0 victory over the eventual Ivy champion was “the best win” he ever had. Penn was the low spot. Dart- mouth failed by inches to gain a first down in the fourth quarter when it had the ,ball on the Quakers’ two-yard line. “The of- ficial said we missed the first down, but it sure didn’t look that way in the film. We didn’t play well offensively. It was probably our poorest-played game, and you hate to go out that way,” Crouthamel says.

There were successes and disap- pointments during the season. Nick Lowery, Dartmouth’s talented kicking specialist, booted his 51st consecutive point-after-touchdown in the 13-10 loss to Brown and eclipsed the record of Ted Perry ’73 for career field goals with 22, in- cluding two game-winners in 1977. A dis- appointment was co-captain Curt Oberg’s failure to set the all-time Green career rushing record. The senior fell 95 yards shy of the mark when he reinjured his right thigh in the Brown game. Oberg sat out the last game against Penn and had to settle for third on the list, 1,693 yards in 391 carries for a 4.32 average and 11 touchdowns, behind Rick Klupchak (1,788 yards) and Crouthamel (1,763 yards).

A nine-man committee, chaired by Seaver Peters, Dartmouth’s director of athletics, began a national search in November to find a successor to Crouthamel. Serving with Peters were Ron Campion ’55, chairman of the Dartmouth College Athletic Council; Alfred Quirk ’49, deputy director of admissions; Oberg and Jim Vailas, co-captains of the football team; Charles Wood, History Department chairman and a former Harvard football player; David Lemal, professor of chemistry and a former Amherst football player; Leonard Nichols ’77, assistant director of financial aid and a former Dartmouth player; and Leo McKenna, captain of the 1955 Dartmouth squad. “We hope to have the job completed and a new coach selected by the first of the year at the very latest,” Peters says.

Despite his impending departure, it has been business as usual at the football office for Crouthamel and his assistant coaches, most of whom are faced with finding other employment. “We’re doing the same things now that we did at this time during the last six years,” says Crouthamel. He has been working on the team’s highlights film, making alumni club talks, and plan- ning a two-week post-Thanksgiving trip

with the rest of his staff to recruit future Dartmouth players.

His resignation does not give Crouthamel any great sense of relief. “On the contrary, I feel a great loss. The pain of that loss would be eased a bit if I knew what I was getting into. The fact that we don’t know makes it a little shaky. The toughest thing for me will be when I have to move out of this office and the home we live in. Then it’s going to be tough no job and no place my family can call home.”

He would like to stay involved in foot- ball, although not on the sidelines: “I’d possibly like to do some color. I think I know enough about the game to make some meaningful comment. But I don’t an- ticipate going to Dartmouth football games for a while. I think it would be very difficult, especially the emotional involve- ment. It’ll be tough enough to go to any game unless I’m doing something while I’m there, like color.”

Crouthamel has seen only one Dart- mouth football game in which he was not involved as either a player or coach. That was in Hanover back in 1960, when he joined the old Boston Patriots after being released by the Dallas Cowboys. “I was also scheduled to see Dartmouth-Harvard that year but was on the Patriots taxi squad and they called from Oakland and told me to meet them in Denver. In fact, I had to cancel my first date with my future wife,” he recalls. “But I got her a stand- in.”

Crouthamel admits he hasn’t seen many football games as a spectator. But he’ll be around eventually. “I’ve heard a lot about tailgating,” he says.

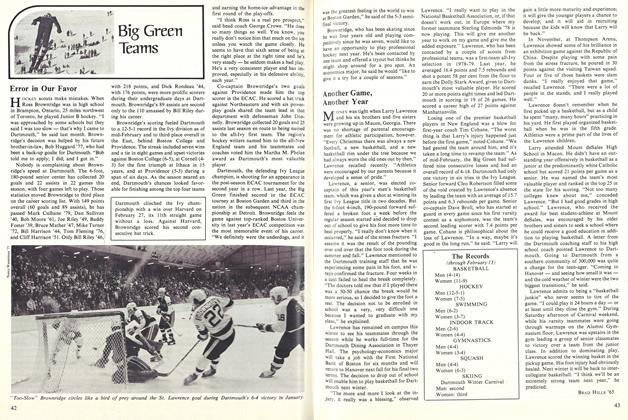

Jake Crouthamel rode the crest of joy at Yale but descended into gloom after the Brown loss.

Jake Crouthamel rode the crest of joy at Yale but descended into gloom after the Brown loss.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Story: His Grandmother and Vincent

December | January 1977 By Howard Webber -

Feature

FeatureThe Well-Tempered Synclavier

December | January 1977 By Woody Rothe -

Feature

FeatureReflections on an $8-million post office The Hopkins Revolution

December | January 1977 By Henry B. Williams -

Article

ArticleResident Rotiferologist

December | January 1977 By S.G. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

December | January 1977 By THOMAS G. JACKSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

December | January 1977 By STEPHEN D. SEVERSON

Brad Hills ’65

-

Sports

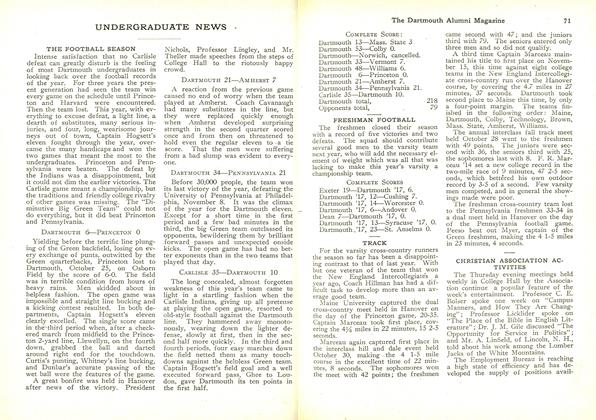

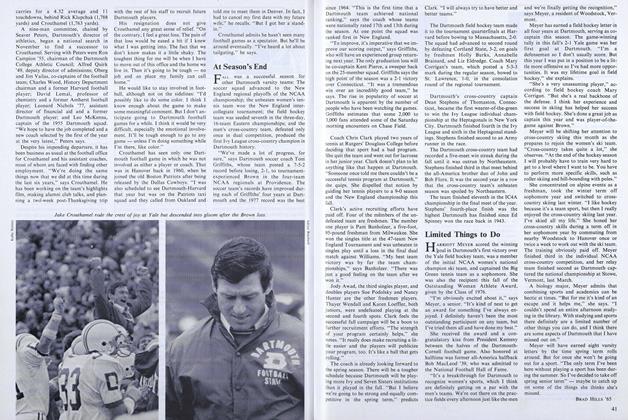

SportsTHE SCORES

DEC. 1977 By Brad Hills ’65 -

Sports

SportsAt Season’s End

DEC. 1977 By Brad Hills ’65 -

Sports

SportsLimited Things to Do

DEC. 1977 By Brad Hills ’65 -

Sports

SportsError in Our Favor

March 1980 By Brad Hills ’65 -

Sports

SportsAnother Game, Another Year

March 1980 By Brad Hills ’65 -

Sports

SportsHurting

June 1980 By Brad HIlls ’65