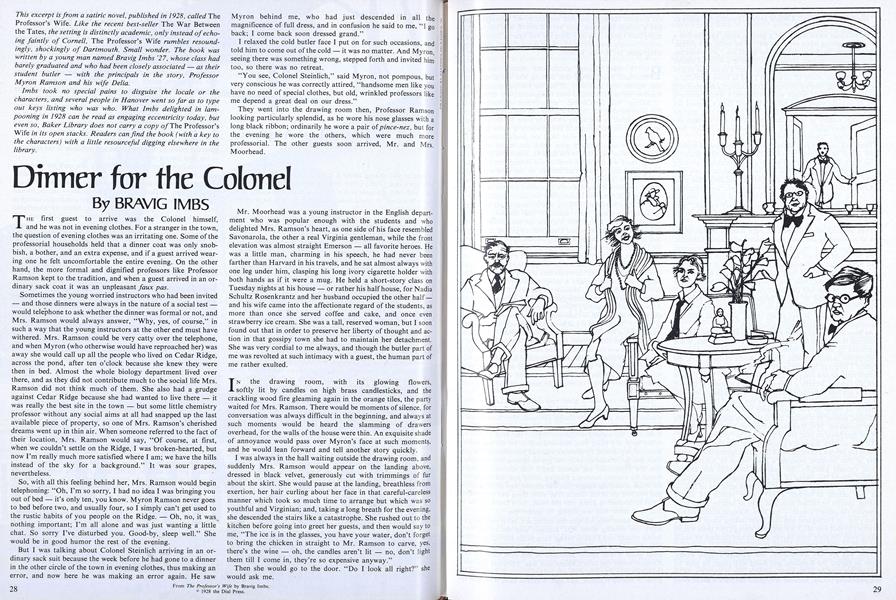

This excerpt is from a satiric novel, published in 1928, called The Professor's Wife. Like the recent best-seller The War Between the Tates, the setting is distinctly academic, only instead of echoing faintly of Cornell, The Professor's Wife rumbles resoundingly, shockingly of Dartmouth. Small wonder. The book waswritten by a young man named Bravig Imbs '27, whose class hadbarely graduated and who had been closely associated - as theirstudent butler - with the principals in the story, ProfessorMyron Ramson and his wife Delia.

Imbs took no special pains to disguise the locale or thecharacters, and several people in Hanover went so far as to typeout keys listing who was who. What Imbs delighted in lampooning in 1928 can be read as engaging eccentricity today, buteven so, Baker Library does not carry a copy of The Professor's Wife in its open stacks. Readers can find the book (with a key tothe characters) with a little resourceful digging elsewhere in thelibrary.

THE first guest to arrive was the Colonel himself, and he was not in evening clothes. For a stranger in the town, the question of evening clothes was an irritating one. Some of the professorial households held that a dinner coat was only snobbish, a bother, and an extra expense, and if a guest arrived wearing one he felt uncomfortable the entire evening. On the other hand, the more formal and dignified professors like Professor Ramson kept to the tradition, and when a guest arrived in an ordinary sack coat it was an unpleasant faux pas.

Sometimes the young worried instructors who had been invited - and those dinners were always in the nature of a social test - would telephone to ask whether the dinner was formal or not, and Mrs. Ramson would always answer, "Why, yes, of course," in such a way that the young instructors at the other end must have Mrs. Ramson could be very catty over the telephone, and when Myron (who otherwise would have reproached her) was away she would call up all the people who lived on Cedar Ridge, across the pond, after ten o'clock because she knew they were then in bed. Almost the whole biology department lived over there, and as they did not contribute much to the social life Mrs. Ramson did not think much of them. She also had a grudge against Cedar Ridge because she had wanted to live there - it was really the best site in the town - but some little chemistry professor without any social aims at all had snapped up the last available piece of property, so one of Mrs. Ramson's cherished dreams went up in thin air. When someone referred to the fact of their location, Mrs. Ramson would say, "Of course, at first, when we couldn't settle on the Ridge, I was broken-hearted, but now I'm really much more satisfied where I am; we have the hills instead of the sky for a background." It was sour grapes, nevertheless.

So, with all this feeling behind her, Mrs. Ramson would begin telephoning: "Oh, I'm so sorry, I had no idea I was bringing you out of bed — it's only ten, you know. Myron Ramson never goes to bed before two, and usually four, so I simply can't get used to the rustic habits of you people on the Ridge. — Oh, no, it was nothing important; I'm all alone and was just wanting a little chat. So sorry I've disturbed you. Good-by, sleep well." She would be in good humor the rest of the evening.

But I was talking about Colonel Steinlich arriving in an ordinary sack suit because the week before he had gone to a dinner in the other circle of the town in evening clothes, thus making an error, and now here he was making an error again. He saw Myron behind me, who had just descended in all the magnificence of full dress, and in confusion he said to me, "I go back; I come back soon dressed grand."

I relaxed the cold butler face I put on for such occasions, and told him to come out of the cold - it was no matter. And Myron, seeing there was something wrong, stepped forth and invited him too, so there was no retreat.

"You see, Colonel Steinlich," said Myron, not pompous, but very conscious he was correctly attired, "handsome men like you have no need of special clothes, but old, wrinkled professors like me depend a great deal on our dress."

They went into the drawing room then, Professor Ramson looking particularly splendid, as he wore his nose glasses with a long black ribbon; ordinarily he wore a pair of pince-nez, but for the evening he wore the others, which were much more professorial. The other guests soon arrived, Mr. and Mrs. Moorhead.

Mr. Moorhead was a young instructor in the English department who was popular enough with the students and who delighted Mrs. Ramson's heart, as one side of his face resembled Savonarola, the other a real Virginia gentleman, while the front elevation was almost straight Emerson - all favorite heroes. He was a little man, charming in his speech, he had never been farther than Harvard in his travels, and he sat almost always with one leg under him, clasping his long ivory cigarette holder with both hands as if it were a mug. He held a short-story class on Tuesday nights at his house - or rather his half house, for Nadia Schultz Rosenkrantz and her husband occupied the other half — and his wife came into the affectionate regard of the students, as more than once she served coffee and cake, and once even strawberry ice cream. She was a tall, reserved woman, but I soon found out that in order to preserve her liberty of thought and action in that gossipy town she had to maintain her detachment. She was very cordial to me always, and though the butler part of me was revolted at such intimacy with a guest, the human part of me rather exulted.

IN the drawing room, with its glowing flowers, softly lit by candles on high brass candlesticks, and the crackling wood fire gleaming again in the orange tiles, the party waited for Mrs. Ramson. There would be moments of silence, for conversation was always difficult in the beginning, and always at such moments would be heard the slamming of drawers overhead, for the walls of the house were thin. An exquisite shade of annoyance would pass over Myron's face at such moments, and he would lean forward and tell another story quickly.

I was always in the hall waiting outside the drawing room, and suddenly Mrs. Ramson would appear on the landing above, dressed in black velvet, generously cut with trimmings of fur about the skirt. She would pause at the landing, breathless from exertion, her hair curling about her face in that careful-careless manner which took so much time to arrange but which was so youthful and Virginian; and, taking along breath for the evening, she descended the stairs like a catastrophe. She rushed out to the kitchen before going into greet her guests, and then would say to me, "The ice is in the glasses, you have your water, don't forget to bring the chicken in straight to Mr. Ramson to carve, yes, there's the wine - oh, the candles aren't lit - no, don't light them till I come in, they're so expensive anyway."

Then she would go to the door. "Do I look all right?" she would ask me.

"Beautiful, as always," I would answer, opening the doors to the drawing room.

Her entrance was a signal for a general upset, and she had a genius for arriving when everyone was in the midst of a phrase. "Oh, sit down, sit down, don't bother about me," she would say in that gay-lady manner, crossing the room in a series of billows to Mrs. Moorhead. "How are you, my dear? I'm so glad you've come." Then she would sit down and I had to listen carefully at the door, for the interval between Mrs. Ramson's entrance and my announcement of dinner was a nice one; I would receive a kind of thought wave from her finally, and then I opened the doors abruptly, but not too abruptly, and took one step into the room, and, staring at the window in front of me, I would announce pretentiously, but not too pretentiously, in my best Eastern accent, "Dinner is served."

Then, as I took my post at the doorway, glacial and immobile, there would be a general scramble for partners. Mrs. Ramson never had half women and half men at a party, because one of her entertaining principles was that a woman was equal to two men in the amount of conversation they did. At this dinner the ratio was two to three, but it generally was two to four, and sometimes two to five. The latter ratio was for celebrated women, because they always talked twice as much as an ordinary woman. "You must expect that a celebrated woman will glitter," Delia would say.

Then the party would file past me, Mrs. Ramson in high spirits just at anticipating the wine and thinking of Colonel Steinlich, who was enjoying a real chic at the moment - the president knew he would be good advertising for the college - and who must have turned down three dinner engagements in favor of the one he had accepted. But then Mrs. Ramson had a high reputation as a cook in the town, and though the dinners were always the same - Myron and Delia had evolved a perfect dinner and scarcely ever varied it: hors d'oeuvres, consomme, Japanese baked crab, roast chicken, potatoes, lettuce salad, and a lemon sherbet - there was always plenty to eat, which was quite extraordinary among professorial households.

As soon as they had passed me, I would rush into the drawing room and blow out all the candles and add a log to the fire. When I returned to the dining room, the guests would have been all comfortably seated and Mrs. Ramson would exclaim, "Oh, the candles! I forgot to light the candles! Now the hostess has made a terrible mistake and everyone can be at their ease." Then I would light the candles, already a little angry that a dinner had to start out on a left foot to be right according to Mrs. Ramson's notions. Of course, everyone felt ill at ease for the rest of the dinner, especially as most of the guests were not accustomed to the elaborate service of a butler and table rules differed in almost every household. Mrs. Ramson wanted two butlers, but Myron put his foot down on that. He said it would be "putting on side."

Of course, Mrs. Ramson's gaucherie was also the springboard needed for Myron's favorite small talk, the etiquette books which were at that moment enjoying a great vogue in America. He would recount gleefully the questions he could not answer: "Where should the owner of the car sit when someone else is driving?" or "What guests should a hostess serve tea to first - the ones nearest or farthest away?" When Myron got started talking, usually he did not stop, and often he held up a course - generally the dessert course - and Mrs. Ramson would tell him "hurry up" in Portuguese and then begin talking about Brazil in an effort to shut him off. I learned soon enough that there was no taking away the plate from Myron until he had finished; he would say, quite audibly, "Not yet, please."

That was not like Swinnerton, that famous English writer, when he visited the Ramsons and dined with them; he took no chances but held on to his knife and fork, one in each fist, as he stopped eating to talk, because in England the plate is taken away the moment the knife and fork are laid down. Swinnerton never had a college education, and Mrs. Ramson said the lack of it really didn't show. The only thing she had against Swinnerton, or rather the only thing she could not get reconciled to, was his deep admiration for Arnold Bennett.

BUT I was talking about this dinner for Colonel Steinlich. The Colonel that evening was not given to talk, and replied very succinctly to all the leading questions Mrs. Ramson started. She began once in a general way about skiing.

"Skiing," said the Colonel, "ees a matter of stomach nerves. Zhe stronger zhey are, ze more farzer can you chump"; and that was all. I think he was angry about the wine, for he took a good big drink in the beginning and then drank only water afterwards. Nobody who really liked wine liked the product Mrs. Ramson made except an elderberry wine which she served very rarely. When the wine was made in the autumn, something always went wrong: there was too much yeast or not enough, the grapes were not good or they weren't ripe enough, or the wine was strained too much or not enough - anyway, something always went wrong, but Mrs. Ramson always discovered a virtue in it and got very gay at dinner and flushed, and breathed rapidly.

Mrs. Moorhead said nothing at the table at all except how delicious everything was, especially the sherbet. That was enough to endear her to Mrs. Ramson, for the sherbet was Mrs. Ramson's own invention and there was no getting around it, it was good. But she was terribly fussy in making it. I had to cut the ice just so; if there had been a way to cut the ice in cubes she would have liked that better; I had to make a prayer when I put the salt in the ice, for once a little salt got into the fruit juice and ruined the sherbet, and the whole next week I was reminded that people who couldn't make a sherbet wouldn't turn out to be anything much anyway, because the faculty of following directions was the most important one in carving out a success in life. After she had put the fruit juice in - made of lemon and oranges and a little lemon peel - there was an unholy amount of grinding to be done. Then, when it had been made and served - always in season with a spray of mint or a candied rosebud - I had what was left on the little wooden paddles to myself, and it seemed to me that that was the best part of the sherbet. I always had to eat it quickly, for they would be ready for coffee in the drawing room almost immediately; besides, I had to chase out to the drawing room around outside and enter by the side door, so that the guests wouldn't see me, to relight the candles and add a log to the fire.

The coffee urn was a great rosy copper one, and it always trembled on its pins when I carried it into the drawing room, the alcohol burner underneath flaring like mad. Mrs. Ramson got so intense on watching it, for she was sure I would stumble and spill it all over the expensive Chinese rug - the kind Myron had rolled upon as a babe, Mrs. Ramson said - for she had had one beautiful rug spoiled by students who had just come off the oiled road and left tracks all over; she got so intense just watching it that she hypnotized me almost and I had visions of standing frozen for eternity holding a flaming coffee urn. All the guests in the room sensed the danger that was abroad, and stopped talking and watched me in the silence. The worst thing was the two steps I had to descend in going into the room, for I could not see my feet and there was no railing to guide me.

Well, I never once fell with that coffee urn, but it was really too much one evening when Mrs. Ramson said the coffee wasn't strong enough and I had to take it back to the kitchen and return with it the same evening five minutes later. I breathed a sigh of relief when it was finally deposited at the little table by Mrs. Ramson where the little Chinese idol was. The little idol was a malicious-looking thing with only half an arm - it was a real one given to Bishop Ramson, and Mrs. Ramson liked it because she said so many prayers had been made to it it had become really scornful. The idol was beautifully carved and it did seem to have a nasty spirit in it. I always felt triumphant when I put the urn down beside it, and it always seemed furious.

Then would ensue the how-many-lumps-and-do-you-take-cream period. Mrs. Ramson would always ask Myron in Portuguese - "Simplis ou com lache?" - as he always changed his mind from one dinner to another. After the coffee he would smoke a white meerschaum pipe - Delia insisted on an appropriate pipe for evening wear - and begin talking on one of his favorite subjects, his book on "Creative Criticism" that was begun but never finished because he was always changing his ideas and he never seemed to have the time. The first chapter began, "Much ink has been spilled on the question, What is art? ..."

THE evening, on the whole, was not a brilliant one. Colonel Steinlich once got started about Austrian mountain lodges, but Mrs. Ramson could not resist breaking in and telling about an exciting mountain adventure she had had near Grenoble, and the Colonel, being interrupted, became moody and stared at the fire the rest of the evening. Delia and two other girls were climbing the mountains when suddenly a storm broke. "There we were," said Delia, "in the midst of those frowning mountains, far from our pension. The rain began falling heavily, the lightning flashed, and the thunder echoed in the mountains in a terrifying way. Luckily one of the girls, I think it was myself, espied a light in the window of a mountaineer's cottage not far distant. We hastened to it, and the two old French peasants took us in, and they were charming, and the old lady taught me how to make a peasant soup which is really delicious and, in the good French manner, costs next to nothing. Just water and onions, seasoning, and lots of bread. You boil the bread right with the soup, and it expands and expands and expands and takes up a lot of room in the 'tummy,' doesn't it, Myron?"

Myron, who had been listening, replied absent-mindedly, "Yes," and then continued talking to Mr. Moorhead about Sherwood Anderson. "I must confess," said Myron, "that for all his unpleasant preoccupation with sex the man does not write badly."

Mr. Moorhead, who was a young man and sympathetic to the moderns, said that he had always thought Mrs. Edith Wharton was the greatest writer in America but after reading "The Triumph of the Egg" he thought that Anderson was more deserving of the title.

"Oh," said Myron, "it's difficult to say."

"Anderson has a very clear and vivid way of presenting the mind of his characters," said Mr. Moorhead.

"Yes, but what irritates me," answered Myron, "is that the minds he presents are always cracked minds. Now, you take Conrad; he never forgets the sublimity of the human being; even The Nigger of the Narcissus has a certain divinity to it."

"But at least," said Mr. Moorhead, "you will admit that technically he is much in advance of that writer the reviews are praising so highly, Dreiser."

"Oh, Dreiser!" broke in Mrs. Ramson scornfully; "Dreiser, that blunderbuss!" She was tiring of the domestic conversation with Mrs. Moorhead - later she said thank goodness that Mrs. Moorhead wasn't one of those dreadful intellectuals.

I find his style very lumbering," said Myron.

He must be an impossible person as well as an impossible writer," continued Delia. "I was talking only a week ago with a "Woman who entertained him at luncheon, Mrs. Smythe, you know, the wife of that dear old man who was editor of the Century so long. She said when she announced luncheon to Dreiser he replied, 'Well, I hope it will be good,' and then he ate like a bear."

"Well, my dear," said Myron deprecatingly, "you can't make literary judgments on a man's social behavior."

"Oh, yes, you can," said Delia very positively; "a woman can, I mean; she has her intuition."

Myron smiled tiredly, for he did not like to have his wife interrupt his gentle cross-examination of Mr. Moorhead. "What would you women do without it?" he asked ironically.

The party broke up shortly afterwards and everybody began talking volubly in the hall. Even the Colonel began to expand in the warm, bright light and clicked his heels loudly as he bowed. The hall was plastered light green with a special weave kind of texture. And then, as there was so much gold paint left, Delia got one of her happy intuitions and, while the plaster was still wet, mashed the paint into a powder and then blew the powder into the plaster by means of a piece of macaroni. The gold, so thinly sprinkled on the walls, was not visible except when the light struck it, and then it gleamed but softly, making the hall seem very rich and gay. There was a wall vase of copper filled with flowers. And in that bit of wall which was just under the landing of the stairs was a little niche, the inside painted a dull blue-green which served as a background for a priceless piece of antique Oriental pottery, a Satsuma bowl, which a Japanese prince had presented to Bishop Ramson. The bowl was pale green, almost white, with a cover, delicately decorated with painted flowers. Above the niche swung a pale yellow Venetian lamp, a long cylinder of light, and Mrs. Ramson said the niche was the "heart of the house."

WHEN the guests had finally left, Myron bolted the great arched English door that led into the hall, first making sure that Scarot, who always slipped out while the guests were saying good-by, had entered. The house always seemed very empty just after the guests had left, and the dining room, with the stained goblets standing about, looked quite desolate. The kitchen was always a picture of confusion, because I always had my hands full just with serving and looking out for the meat and dishing out the sherbet to be paying much attention to the symmetrical arrangement of dirty plates and saucers.

Mrs. Ramson would always try to break the heavy atmosphere by being impossibly gay all in a spurt and dancing into the drawing room from the kitchen, where she had been foraging, now with a chicken bone, now with a plate of cold Japanese baked crab that someone didn't eat, and she would call to Myron, who was fixing the fire for the night, "Oh, Myron, aren't you hungry, dear? Come on out to the kitchen and have a bite."

He would follow her out to the kitchen a moment later, while she bustled around clattering dishes and piling them pell-mell all over to make a place in the breakfast nook. She always liked to have something in her mouth; at odd moments of the day she chewed pieces of straw which she plucked nervously from the broom. This always digusted Myron, who would say, "My dear, how can you! It's been all over the floor!"

Then they would sit down to eat, finishing up the chicken and the crab and the salad, and Mrs. Ramson would make a fresh cup of coffee - Java Express, and it was good - and invite me to join them. "I must say," Myron would begin, smiling, "that the dinner was most exquisitely served, as fine as in the great restaurants," and Mrs. Ramson would beam on me, forgetting for the moment that I had totally forgotten to serve the Camembert with the salad and had to be reminded it was in the ice box and that the crackers were just above the molasses on the top shelf in the bright tin box. They would be sitting together then discussing the dinner and the guests until two and three in the morning, the lights blazing all over the house - "lit up like a church," Mrs. Fife said - so that any stray nocturnal traveler would know that one family in the town, at any rate, kept sophisticated hours.

From The Professor's Wife by Bravig Imbs; © 1928 the Dial Press.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

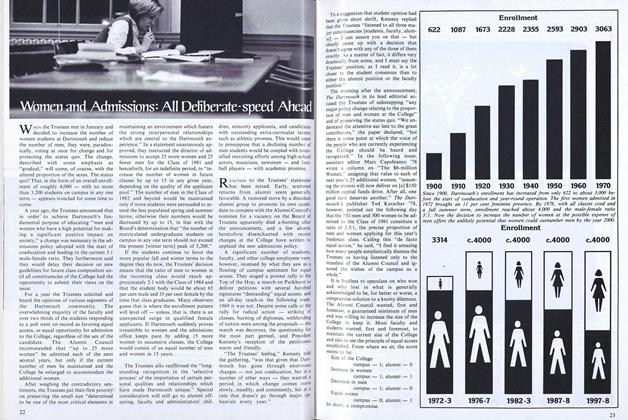

FeatureWomen and Admissions: All Deliberate-speed Ahead

March 1977 -

Feature

FeatureSleep-filled Days, Gambling Nights

March 1977 By BRAD W. BRINEGAR -

Feature

FeatureArtists

March 1977 -

Article

ArticleRambling with Melancholy

March 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleA Versatile, Admirable Teacher With "Every Feature of a Drill Sergeant'(sic)

March 1977 By S.G. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

March 1977 By STEPHEN D. SEVERSON, JACK E. THOMAS JR.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCampus Cosmopolitans

February 1961 -

Feature

FeatureFrom Rap to Ritual

SEPTEMBER 1998 By Everett Wood '38 -

Feature

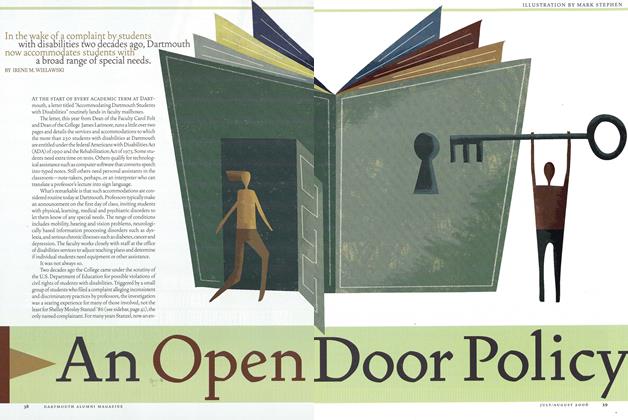

FeatureAn Open Door Policy

July/August 2006 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCAN WE TALK?

MAY 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

Feature"How Ya Gonna Keep 'Em Down on the Farm?"

March 1975 By ROBERT L. HIER -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Overtreated American

Nov/Dec 2003 By SHANNON BROWNLEE