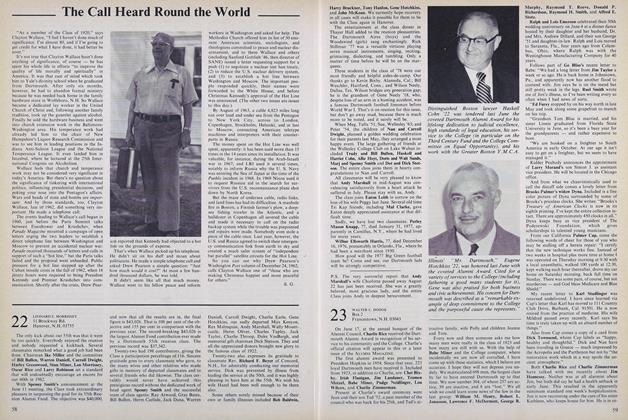

A Versatile, Admirable Teacher With "Every Feature of a Drill Sergeant'(sic)

March 1977 S.G.AT precisely eight o'clock the lecture begins. A hundred and fifty students keep a watchful eye on the large man at the front of Filene auditorium. He explains a point and turns to write on the blackboard behind him. At 8:05, a shadowy figure darts through the back-door door of the auditorium, slithers into the nearest seat, and breathes a sigh of relief: the professor's back is still turned, the chalk still moves across the board. Suddenly the chalk stops midword, the lecture breaks off midsentence. There is silence, profound silence in Filene. From the front of the room issues a greeting, basso profundo and heavy with sarcasm. The lecturer's back is still turned and the disembodied voice rumbles ominously around the room as if from on high. Good morning, Mr. Green. How kind of you to come to our class after all." Another silence, in which young Green curdles with embarrassment and vows never again to be late to Math 3. The lecture is resumed midsentence and the chalk begins again to write where it left off.

That is one story they tell about William His Slesnick, professor of mathematics. Another has it that he knows the name, face, hometown, family background, extracurricular activity, and possibly the blood type of each one of his students by the end of the first week of classes. To those classes you must not arrive late, you shall not wear a hat, or come barefoot, or bring your breakfast, your coffee, or your dog. (All of which seems outrageously repressive to the modern student.) "He has every feature of a drill sergeant," reads the student Course Guide. "He even runs his lectures as though he was still in an army camp." ("Honestly!" grumbles Slesnick, "I'm a Navy man.")

"Professor Slesnick is not universally admired," says Richard Crowell, head of the Math Department. "Some of the students hate his guts." Maybe so, but the Slesnick-haters are few, and in the face of the widespread (if not universal) admiration he inspires around Dartmouth, they seem insignificant. Most of them - like that same Course Guide writer - admit, in the end, that "if one finds the courage to go to see Professor Slesnick outside of class, he will discover that Slesnick is approachable, helpful, and actually a human being." "He cares," attests Crowell. "Oh, yes. He cares."

Slesnick is not just a garden-variety curmudgeon with a heart of gold. He's a versatile person who has done interesting things, most of which you can learn about from the man himself. His candor is complete - both an honest awareness of his limitations and a forthright pride in his accomplishments. It's an engaging combination. "I love to talk about myself," he says, without coyness, and then does - for two solid hours, not a minute of which is dull.

His academic background is an astonishing tangle of schools and degrees. "Only John Kemeny and my mother could understand my schooling," he says. He entered the University of Oklahoma (his home state) as a freshman in 1941. After Pearl Harbor, NROTC student Slesnick applied for and won a place at the Naval Academy, from which he graduated with a B.S. in 1945, "one class ahead of Jimmy Carter." (No, he doesn't remember Midshipman Carter: "He was in another battalion.")

Everyone at Annapolis took the same course in those days, Slesnick explains, except for language - and even your language was determined by a set of regulations based on a logic peculiar to the military mind. If you had had Latin in high school, for instance, you took Portuguese at Annapolis. Slesnick had had Latin, and so Slesnick took Portuguese. In fact, with characteristic thoroughness, he qualified as a naval interpreter-translator in it. "Once, at a cocktail party in Port Said," he says wryly, "I found it useful to be able to speak Portuguese. All in all, it was not a very good education." After the Navy, Slesnick returned to Oklahoma for "a solid undergraduate math major," taking a second senior year and another degree, a B.A.

Why mathematics? "Oh, originally, I guess, because I could do it better than most other people," he says candidly. "Later the beauty of the subject - the clarity, the structure, the elegance of it -attracted me." Then, too, C. E. Springer, head of Oklahoma's math department, lived next door in Norman, and young Slesnick was deeply impressed by him. "I was a hick," he recalls. "He was a Chicago Ph.D. and a Rhodes Scholar. I thought he was god."

Slesnick set out in Springer's footsteps by making successful application for a Rhodes scholarship from Oklahoma, and in 1948 off he went to England to study mathematics at Jesus College, Oxford - "a diamond in the rough among lots of fancy people," as he puts it. Two years later he was B.A. (Oxon.), and in four more became M.A. (Oxon.).

Next, a doctorate at Harvard. But there his GI bill and his bonds quickly ran out, and Slesnick found himself trying to study between jobs tutoring, grading, and doing computations for a Boston hospital. "I ate on a dollar a day and lost 35 pounds," he recalls. "After two years of it, I ran out of gas." He remembers for a minute and then adds, "Harvard is not a friendly place."

He took an M.A. from Harvard and left Cambridge to take a job teaching secondary school mathematics at St. Paul's in Concord, New Hampshire. From there he first came to Dartmouth in 1958 for a year's instructor ship. Then, in 1962, John kemeny brought him back and turned over into his competent hands the manifold and complex matters of mathematics placement. "We at Dartmouth," says Kemeny, "are proud of the fact that our entering students are very carefully placed in a mathematics program that offers no fewer than eight beginning levels."

For years now, Slesnick has administered the entire placement program, as well as taught many of the early courses. He acts as adviser to first-year students for the department, oversees its freshman week, and is always present at registration to resolve tangles and to comfort frantic students and administrators. Crowell speaks of Slesnick's work with the same relief and gratitude expressed by the reminiscing Kemeny. "If Bill Slesnick is in charge of a program, I can forget about it," says Crowell. Kemeny calls Slesnick "the conscience of the department, making sure that first-year students get first-rate teaching in mathematics."

It is understandable, then, that Kemeny fought to keep Slesnick here, going after a tenured professorship for him with characteristic Kemeny tenacity. And, with characteristic Kemeny success, he got it, despite the fact that Slesnick never returned to complete his Harvard doctorate. Some were hung up about the doctorate, explains Kemeny, who points out that Slesnick holds more earned degrees than any other member of the faculty - three bachelor's and two master's. Asked whether he minds being the department's only professor without a Ph.D., Slesnick says, "No - I don't think so. I feel I can teach as well as any of the others." He might have said - perhaps he almost did say - that he can teach better than many of the others.

Certainly the students think so, as the course guides testify. And the sincerity with which Slesnick describes "the fun of convincing people who don't understand them that the techniques of mathematics are learnable and fun" marks him as a teacher by nature. He asserts that the formality of his classroom is principally the result of his upbringing. It is not simply quirkiness, but a serious attitude toward work. "I am paid to teach mathematics. That's my business."

Are the stories about his teaching apocryphal? That's not clear. "It's not true that I know all the students' names," says Slesnick himself. "I know just enough to Keep them off balance." Nor is it true that he has eyes in the back of his head with Which to catch tardy students. Nor is he sarcastic when he does catch one: "I don't say a word, in fact. I stop lecturing when a latecomer enters; I watch until the student is seated; and then I resume where I left off." He adds with a small smile: "It's very effective, that silence. They feel it's better not to come at all than to come late. Of course, it helps to be six foot three and have a deep voice." Here his eye sparkles fleetingly. "I can prove almost anything in a calculus class by intimidation."

One of Slesnick's many extracurricular activities is scouting, to which he has devoted years of service. It has taught him leadership, he feels, and he finds the international contacts exciting. He has attended jamborees in Canada, Japan, and Norway, as well as in this country, and he looks forward to Iran in 1979. He has trained as a leader at the famous Gilwell Park in the Epping Forest of England, mother country of scouting, and on his living room wall are displayed three of scouting's most coveted badges: that of the Order of the Arrow, the Silver Beaver, and the Silver Antelope. Each is awarded, Slesnick explains, "for distinguished service to boyhood." (He wrinkles his nose in distaste of the phrase, but it's clear that he values the distinctions.)

Slesnick lives among mementos, of places, of events, of friends, of relatives. He shows proudly the collection of Chinese snuff bottles left him by his aunt because he often admired them - tiny, intricate vessels carved from exquisitely colored pieces of jade, tourmaline, and cinnabar. A sideboard in the dining room is devoted entirely to mugs - some 75 or 80 of them, each of which commemorates a scouting event Slesnick has attended. Most of the furniture has a family history, and Slesnick displays with affection the massive brass mortar-and-pestle which belonged to his Lithuanian great-great-great-grandmother and was brought over "from the old country" by his grandmother. Asked whether he lives alone by choice or chance, he answers, "the latter."

For all the austere public image, the commanding physical bulk, and the stentorian voice, Slesnick is a cordial person and a sensitive, astute judge of character by all accounts of those who know him. And like the man says, he cares. He remembers not only names and faces, but also idiosyncrasies and prejudices. He may have inherited a collection of snuff bottles, and he may have picked up a collection of mugs, but some of his greatest energies and most impressive talents have gone into his collection of friends.

And there is more, much more. This is only a portion of all there is to know about William Slesnick. Just now someone said, "Have you heard about Slesnick's Wizard of Oz T-shirt?"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDinner for the Colonel

March 1977 By BRAVIG IMBS -

Feature

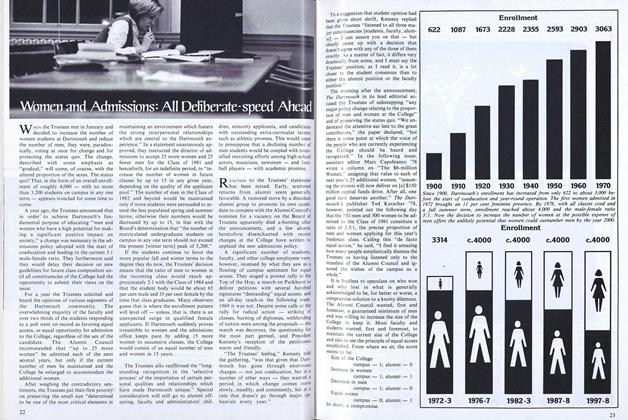

FeatureWomen and Admissions: All Deliberate-speed Ahead

March 1977 -

Feature

FeatureSleep-filled Days, Gambling Nights

March 1977 By BRAD W. BRINEGAR -

Feature

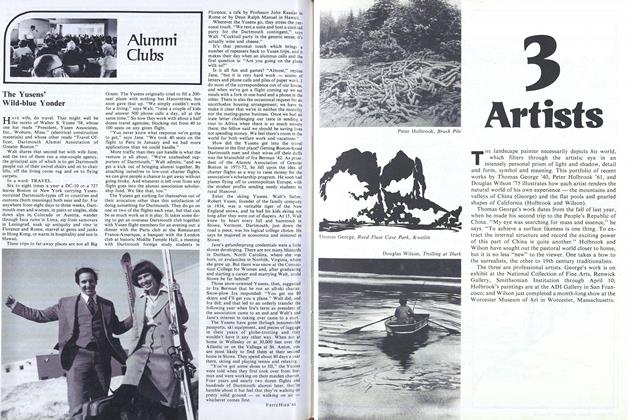

FeatureArtists

March 1977 -

Article

ArticleRambling with Melancholy

March 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

March 1977 By STEPHEN D. SEVERSON, JACK E. THOMAS JR.