Notes on medieval beasts and the versatile writer who modernizes them, and memorials for a Dartmouth organist.

March 1977Notes on medieval beasts and the versatile writer who modernizes them, and memorials for a Dartmouth organist. March 1977

Elsewhere in these pages Henry Terrie writes about one of the most significant books of 1976, Jefferson's Nephews by Boynton Merrill Jr. '50. Since its publication early last year Merrill's account of the homicidal insanity of two brothers and the brutal murder which ensued in Kentucky in the early 19th century has met with unusually unanimous critical applause for its scholarly thoroughness, its crisp, readable prose, and the moral insights of its author. A succes d' estime from the start, it has now received the penultimate accolade: nomination for a Pulitzer Prize.

Amid all the plaudits for Jefferson's Nephews it should also be recorded that Merrill published two books in 1976, not one. His second was ABestiary (University Press of Kentucky, 70 pp., $7.50). Merrill seems a writer for all seasons, for at first glance it would be difficult to imagine a book more unlike Jefferson's Nephews than his Bestiary. Whereas the former is based on historical scholarship and reconstructs an event which actually occurred in frontier Kentucky, the latter is a construct of the imagination, a book of poems with generic antecedents in, of all things, the medieval period.

A bestiary seems an anomoly in the 20th century. It flourished in the spiritual and intellectual climate of the Middle Ages; it is often pointed to by scholars, indeed, as perhaps the single literary genre which reflects par excellence the medieval temper. Not to put too technical a point on it, a bestiary was an assemblage of accounts, either in verse or prose, of the habits and legendary lore connected with animals. Typically medieval, it was designed not to amuse but to instruct in matters of religious belief and morality, the account of each animal serving merely as the text or vehicle for a religious homily, usually of the somber, medieval memento mori type.

What can a 20th-century writer do with such an apparently uncongenial form? If it is Boynton Merrill, plenty. There are few homilies in Merrill's well-wrought poems; or rather, if the homilies are there they are implied, as in modern poems, rather than overt, as in medieval. But the spirit of the original genre is skillfully maintained. Woven fleetingly and unobtrusively into the poems is the same leitmotiv of Classical allusion which characterized the medieval bestiary, and the illustrations, done by Robert James Fosse, though they have nothing of the stiff, one-dimensional, medieval wood-block look about them, nevertheless embody something of the immediacy, even the grotesque qualities, of their medieval predecessors.

But the spirit of the book seems modern. The spareness of Merrill's small, often haiku-like poems clearly suggests the modern idiom. Modern, too, is the technique by which Merrill stitches his single poems together into a piece which has, in the end, a single, unified effect. Reverberations echo from poems so insistently that they become themes. The body of the mule which dies in one poem becomes the breeding ground in the second for flies, which in their turn are prospective prey in the third for the spider. It is as if to suggest some ironic connection between what the Middle Ages called, in lofty term, the Great Chain of Being, but which we call, in grislier phrase, the food chain.

Given voices by their author's imagination, Merrill's animals speak not out of the 12th century but the 20th. They are post-Darwinian. The tone of the book is somber but not in the medieval sense. And so in the end perhaps Boynton Merrill's two books of 1976 are not as dissimilar as they may seem. Both are deeply rooted in the modern consciousness and spring from the same imaginative view of our own place and time.

The late Louis Milton Gill Jr., College organist and professor of music from 1959 to 1968, when he was killed in the crash of a Northeast Airlines plane on Moose Mountain, has been honored in 1976 by several significant events. Four of his musical compositions were published for the first time: Three ChoralPreludes for Organ (N.Y., G. Schirmer Co.) and Processional for Organ (Chapel Hill, N.C., Hinshaw Music, Inc.). And late in the year the Milton Gill Memorial Organ was dedicated at St. Thomas' Episcopal Church in Hanover.

Begun in 1968 after the plane crash, the organ project grew out of many gifts initially received at St. Thomas' to honor Gill.

On November 21, 1976, James D. Ingerson. choirmaster at St. Thomas', played a memorial concert on the new organ which included a portion of Gill's own Partita. The concert was followed by an evensong service of dedication during which the three major pieces which Gill had written for choir and organ were sung.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDinner for the Colonel

March 1977 By BRAVIG IMBS -

Feature

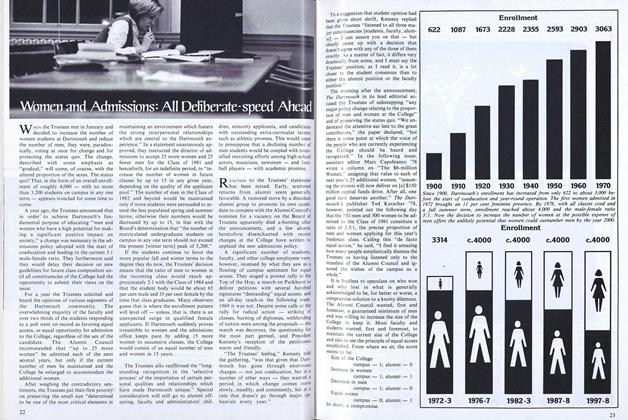

FeatureWomen and Admissions: All Deliberate-speed Ahead

March 1977 -

Feature

FeatureSleep-filled Days, Gambling Nights

March 1977 By BRAD W. BRINEGAR -

Feature

FeatureArtists

March 1977 -

Article

ArticleRambling with Melancholy

March 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleA Versatile, Admirable Teacher With "Every Feature of a Drill Sergeant'(sic)

March 1977 By S.G.

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

JANUARY 1971 -

Books

BooksWHO'S WHO AMONG THE MICROBES

MARCH 1930 By A. H. Chivers -

Books

BooksPROPAGANDA COMES OF AGE.

NOVEMBER 1965 By CHAUNCEY N. ALLEN '24 -

Books

BooksTHE AESTHETICS OF THE RENAISSANCE LOVE SONNET: An Essay on the Art of the Sonnet in the Poetry of Louise Labe

MARCH 1963 By FRANK G. RYDER -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN ENGLAND,

April 1948 By HERBERT F. WEST '22. -

Books

BooksDIDEROT, THE TESTING YEARS,

July 1957 By JOHN HURD '21