In March 1917, shortly "before the actual declaration of war by the United States, but at a time when it was obvious that a declaration would soon be forthcoming, I attended a rally in Webster Hall held under the auspices of the U.S. Naval Reserve. My friends and I heard about the dangers of Germany's U-boat warfare and about America's developing plans for a huge anti U-boat fleet, to consist at first of commandeered private yachts. There were no recruitment officers present, but all of us were pretty well fired up by the prospect of helping to defend our country while at the same time having a fine summer sailing someone else's yacht, and, not least, freedom from study and classes at a time when such dreary tasks were becoming increasingly difficult to perform. The thought of danger never entered our youthful heads; it never occurred to us that the U-boats might not sit still while we dropped depth bombs nearby.

The meeting was held shortly before spring vacation, and I, together with my Washington friends Stirling Wilson '17, Pete McCoy '16, Dave McCoy '18 and Larry Pope '18, all entrained for the capital for the spring holiday. Along with us was my roommate, Dick Wilder '19, whom my parents had invited to visit.

Washington was seething with war, patriotism, and talk of "the beastly Huns" and somehow or other, without any serious discussion, we each decided, individually, and then as a group, to go to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to enlist in the Navy. And so we did. I cannot remember now whether it was before or after the actual declaration of war, but it was within a few days one way or the other. We were given a few days to go to Hanover to say good-bye and to dispose of our things, then back to Portsmouth to don our Navy Blues. And our pride was unlimited as we strutted around Portsmouth or Boston on days off with our white hats cocked on one side, regular Navy style.

When we reported in, we were given our full complement of blues, whites, pea jacket, hats, blankets, and hammock and shuttled off to the old Southrey, which was moored to a dock and serving as an annex to Portsmouth Naval Prison. We were mingled with the prisoners, most of whom were in for minor offenses, and we were astonished by their kindness in teaching us how to roll our clothes, stow them in bags, how to tie knots, and the like. After kidding us about where to find the hammock ladders, they even showed us how to hang our hammocks and how to get into them without a ladder. It's quite a trick.

The day finally came when we crossed the dock with hammocks and all our other possessions in hand to board the Topeka and to find our assigned quarters. Mine were in a cavernous area below the waterline on C deck (the lowest) in the stern of the ship. The Topeka, an 1,800-ton gunboat, had been built in England and served in the Spanish-American War. She was 35 years old.

Meanwhile, enlistees arrived from Dartmouth and from many other colleges to join us. Our eventual complement of about 200 included men from Lehigh, Williams, Amherst, Bowdoin, and a very special delegation from Kenyon College that I came to know intimately. One, George Brain, became a lifelong friend. I can't remember all the names of the Dartmouth contingent, but in addition to the Washington group and Dick Wilder, I do remember Ed Fiske '19 and his brother Gene '20, Ted Cart '20, Harry Hall '19, Dutch Brummer '19, Red Washburn '19, Benny Mugridge '18, Ginger Bruce '20, Jack Cannell '19, Guy Cogswell '19, Hal Barbour '19, Bob Hopkins 'l4, Cliff Bean '16, Jim Duffy '18, Gil Swett '17, Bill Eads '19, Mose Forrest '10, Eddie Edwards '19, Ray Legg '19, Collie O'Gorman '19, Tom Carpenter '20, and Bill Durkee '20.

And then, of course, there was Greif Raible '19, who deserves special mention. Our group from Washington had fairly extensive sailing experience on Chesapeake Bay, and most of the others had some small-craft experience. Nevertheless, when we were asked by the enlistment officer what rating we wanted, most of us replied "seaman" and were quickly accepted as such. Not so Mr. Raible. He had the foresight to request a commission as an ensign on the basis of his attendance at Culver Military Academy, and he got away with it.

So, when we boarded the Topeka, whom did we find but Ensign Raible ensconsed in his quarterdeck cabin and, appearing from time to time with his sword and white gloves, ready to lord it over us gobs. But he had a sense of humor, and didn't take himself too seriously. And we gave him his comeuppance occasionally, as one day when he was conducting infantry drill on the Navy Yard parade ground. On a given command, by pre-arrangement among the gobs, one platoon went to the right and the other to the left. When Raible recovered from his astonishment, he shouted "Halt" and "Fall Out." After several minutes of hilarious laughter, with Raible joining in, discipline was re-established on his "Fall In" order.

Life aboard the Topeka was a mixture of hard work - polishing brass, scrubbing decks, chipping paint, washing clothes - interspersed with utter boredom. But there were occasional duties of some interest and excitement. We soon took over the Marines' duties of patroling the Navy Yard day and night, and we carried Springfield rifles and live ammunition to do the job. As an S-type submarine was under construction at the time, it was a job of some responsibility. The submarine was housed in a huge shed lighted only by two lamps in the roof, and the guard post inside the shed was a lonely and scary place at night, particularly between midnight and four a.m. Happily, we saved the submarine from sabotage.

Then there were amusing incidents. Access to our C deck quarters was via a ladder well from the upper deck. Our hammocks were stowed during the day in hammock nettings adjacent to the upper-deck railing. We on C deck soon discovered that when we returned to the ship after an evening ashore in Portsmouth, the easiest way to deliver our hammocks to C deck was to drop them down the well and pick them up at the bottom.

The C deck crew was somewhat unruly at times, and not infrequently the banter, joking, and singing continued long after taps had sounded. One night our executive officer, Lieutenant Smyth of the Connecticut Naval Militia, came aboard about 11 o'clock and heard unseemly noises emerging from C deck. Unwisely, he decided to do something about it, and he descended to C deck to deliver an appropriate lecture. No sooner had he started than a C deck sailor came aboard, picked up his hammock and, tossed it down the well. It floored the lieutenant who responded with appropriate sea-going profanity, but by the time he reached the upper deck, the perpetrator had disappeared. Poor Lieutenant Smyth never quite recovered his dignity.

Well, it was fun while it lasted, but there came a day in July when orders came transferring the entire crew of the Topeka to a newly established naval training camp on Bumkin Island in Boston Harbor. This was a demotion as far as we were concerned, especially because the only way ashore was via the Nantasket boats which made occasional stops at the island. But our unhappiness didn't last long. Some of us who were still under 21 were ordered back to college. Others were assigned to officer schools and some to ships.

But none of us will ever forget our days as the crew of the good ship Topeka. They were happy days.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAffirmative Action

April 1977 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

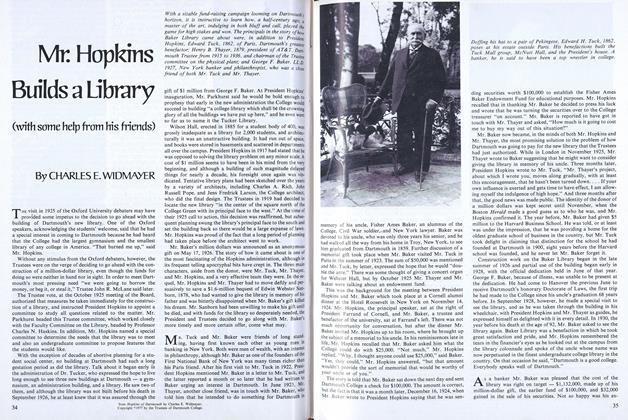

FeatureMr. Hopkins Builds a Library

April 1977 By CHARLES E. WIDMAyER -

Feature

FeatureIf you spent the winter in Buffalo, Imagine This

April 1977 By THOMAS SHERRY -

Feature

FeatureThe Road Not Taken

April 1977 By JOHN S. MAJOR -

Article

ArticleBetween Seasons

April 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

April 1977 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR., LOUIS N. PERRY