Fraternities at a crossroads - again

NINETEEN THIRTY-SIX was a difficult year for the fraternity system at Dartmouth. In response to the growing criticism of these organizations and their role on campus, President Ernest Martin Hopkins appointed a committee, chaired by Professor Russell Larmon '19, to study the situation. The Larmon Committee came up with some surprising conclusions. The majority report stated that "the system of national affiliations of fraternities at Dartmouth College has failed to a very considerable degree both in accomplishing the ends stated in the fraternity charters and in providing the best possible social units at Dartmouth College." The Larmon Committee then recommended the uniform termination of all national affiliations for the 25 fraternity chapters as a solution to these short-comings.

This startling idea stemmed from a widespread disappointment in fraternity life. "Moral principles and strong character do not," observed the report, "necessarily result from the fraternity system at Dartmouth." Even more disturbing was that "fraternities are notoriously reluctant to exert positive group pressure towards the enforcement of minimum standards of conduct."

Dartmouth fraternities were at a crossroads in 1936. The Larmon report reflected dissatisfaction in all segments of the College community: among the alumni, the administration, the faculty, and even the students. A tragic furnace mishap at the Theta Chi house two years earlier, which caused the death of nine undergraduates, further fueled the dispute. But President Hopkins chose to table the Larmon study, explaining his inaction with the comment that he needed time "for review and for undergraduate and alumni sentiment to clarify itself." A young alumnus was appointed the administration's fraternity liaison officer, and then the questions raised by the Larmon Committee receded into the shadow of the approaching war.

The executive response to the issues raised in 1936 was no response at all, and it foreshadowed the pattern of official ambivalence toward the fraternity system that has held the field to this day. Once again a set of questions about the role and value of Dartmouth's main social institutions has arisen. There have been periodic troubles in the years since 1936: occasional student deaths related to fraternity activities, the halftime "riot" at the 1957 Harvard-Dartmouth football game, and the dispute during the mid-fifties over discrimination clauses in charters of many national chapters, which prevented members of minority groups from joining the houses. These episodic traumas often were resolved through the personal clout of the President, but then the times changed.

"Nobody was going to question the authority of a John Dickey in the forties and fifties," explains E. Ronan Campion '55, a member of the Fraternity Governing Board. "But in the sixties undergraduate activism shifted the focus of College officials and chopped away at the administration's unofficial regulation of fraternity houses. When you're defending the integrity of your own inner office [an allusion to the takeover of Parkhurst Hall in 1969], the fact that some guy is sneaking a girl up to the third floor of a fraternity house becomes unimportant."

The feeling that standards have been allowed to slip too far is prevalent among College officials and alumni. On June 24, 1977 The Dartmouth reported that a meeting of the Alumni Council "reaffirmed its concern over the 'deplorable' physical condition of many campus fraternities." Many undergraduates concur with the notion that changes must be made. "We inherited a system that had pretty much run amuck," says Craig Woods '78, a representative on the Interfraternity Council and the Fraternity Governing Board. "Fraternities will eventually be policed in regard to conduct, appearance, safety, etc. But what we're worried about is that our autonomy may be impinged upon in the process. We feel we have certain rights as independent organizations."

The current period of re-examination, perhaps even a crisis situation in terms of the future of Dartmouth fraternities, has raised certain familiar issues along with new questions. The administration is anxious to develop a clear delineation of rules, regulations, and responsibilities that will formalize the relationship between the College and the fraternities. The Trustees and the alumni appear to be most concerned with the physical deterioration of the fraternity properties, and seek to establish an arrangement whereby the houses are properly maintained. The fraternities themselves wish to maintain control over their lifestyle, and have been generally suspicious of attempts to reorganize. Others in the Dartmouth community question certain attitudes they feel are propagated in the fraternities, and lament the social monopoly held by the houses along with the equivocal position of women in the current system.

ONE thing everyone seems to take for granted is the existence of the fraternity system and the probable continuance of this system into the future. None of the many individuals interviewed on this subject expressed a belief that fraternities would die out or be eliminated from campus life. As Dean of the College Ralph Manuel '5B puts it, "There is always a pool of people who want the fraternity experience. Fraternities are a significant part of the overall Dartmouth experience." When asked about the benefits of fraternity life, Manuel referred to his own career at Phi Gamma Delta (now defunct at Dartmouth). "I remember the opportunity to live with 15-20 people senior year and the opportunity to know 60 people with a depth I wouldn't have had otherwise."

Craig Woods believes that the fraternities provide their members with a needed release from the highly competitive academic environment, "interjecting the proper amount of non-seriousness," as he phrases it. "Dartmouth can be a very somber and serious place. Being a member of Beta has helped me loosen up." David Kalapos '78, an Alpha Chi Alpha, agrees with Woods, adding that fraternity life "is tighter living than the dorms. You get really close to people."

Despite Dartmouth's apparent conclusion that fraternities, in one form or another, are good things, some other colleges have summarily closed them down. Williams College made the decision to abolish exclusive social organizations in the 1960s on the basis that they divided what should have been, given the size of the enrollment (under 1,800), a more cohesive campus. A Williams ad- ministrator, who was a fraternity member there, says his school "is a much better place without them." Still, two underground fraternities have recently organized off the Williams campus.

Few people at Dartmouth wish to see the College follow Williams' example. Perhaps the only danger to the system is the fraternities themselves, since some houses are in poor financial shape or are severly dilapidated. The properties are old — the majority date their origins back to the 1920s — and they have endured successive years of hard use. Campion notes that "kids are no more abusive today then before, but now the individual fraternities can't afford to have janitors to clean up the places." Because of the inability of most fraternities to scrape together the roughly $5,000 per year needed to maintain the value of their houses, 20 out of 21 house corporation officers recently claimed that their properties were undergoing a net depreciation. Though "fraternities have always 'trashed' their houses," says Campion, in the past yearly repairs and capital improvements mitigated the damage. Fraternity expenses have of late been consuming, if not exceeding , their revenues, due in large part to increased taxes and particularly fuel costs. At the same time the major sources of income, room rents and dues, have remained "unrealistically low," according to Campion.

Fraternity dues average about $50 per term in social fees and $50 in house charges — figures that have remained relatively steady over the past few years. The room rents charged by fraternities are significantly lower than what the College charges for dormitory accommodations. Kalapos, who has been in charge of most of the audits of fraternity finances for the past two years, estimates the average fraternity room cost to be in the $200-225 range, while most dormitory rooms cost well over $300 per term. These pricing policies have forced the houses to channel all of their meager income toward the cost of merely operating the house, and nothing remains for capital expenditures. Kalapos notes that few houses have savings accounts of any kind. In the current hand-to- mouth situation, loans provide the only avenue for significant improvements in the properties.

Each house (with the exception of Alpha Chi, which is owned by the College) has a ruling corporation, composed of alumni, which theoretically oversees the long-term interests of the fraternity. "The house corporations should see to it that the upkeep gets done," says Dave Kalapos, and many administration officials also point to the corporation as the principal supervisor. But with the exceptions of corporations like that of Theta Delta Chi, the past decade has seen most of these groups become lax in their role. Craig Woods explains this decrease in alumni interest in terms of the break Dartmouth fraternities made with their national organizations in the late fifties and early sixties. "When a lot of the houses went local, the alumni of those houses stopped giving money." The national houses, according to Woods, still have strong alumni corporations and dependable financial support. Woods, a member of Beta Theta Pi, one of six national fraternities still at Dartmouth, claims that many alumni identify with their old national but feel no loyalty to a house that split off to become a local after they left. For example, a former Sigma Chi might no longer feel a proprietary interest in the current occupant of his house, Tabard.

Campion, who is a corporation adviser to his old fraternity, Sigma Nu Delta, points to the difficulty of effectively controlling a house in absentia, since most corporation officers live in distant parts of the country. Some fraternities are pleased with this laissez faire situation since it allows them to run their affairs to their

satisfaction, but when financial difficulties loom — as they have on occasion for many houses — complaints about weak corporations invariably arise.

On the other hand, some house corporations are strong enough to perpetuate chapters even after their viability has become doubtful. Phi Psi, isolated from the rest of the houses due to its secluded School Street location, has had great difficulty attracting members for over four years. The Phi Psi brothers accumulated large debts to the College, developed something of a counter-culture reputation, and tottered on the brink of extinction. Yet, according to Dean Greg Hakanen '75, they managed to convince their alumni corporation to support them each year and the house hung on. In the past year Phi Psi has taken steps to stabilize its own affairs, but its continued presence on campus is a tribute to the power of a strong corporation.

QUESTIONABLE financial practices have also plagued some fraternities. The use of house dues — the money ostensibly allocated for the physical plant — for social activities (mostly beer) has been a drain on the funds available for upkeep. Kalapos says that "some houses do crazy things like get guys to pay in advance when the house gets behind." This effectively mortgages the short-term future income of the fraternity. Another source of money woes among fraternities is their inability to collect on the debts of their members. Kalapos notes that in the recent past the average graduating debt — the amount graduating seniors owed the house after they left — was in excess of $3,000 per house. These debts have been written off all too soon, according to Campion and Manuel, due to the reluctance of fraternity officers to take a hard stance with their prodigal brothers. But Kalapos maintains that the houses have no effective leverage. "Fraternities need a way to force a guy to pay his bill. The College ought to help us." At present the College will help to a limited degree.

Dartmouth's interest in the fraternity system as a social institution is dwarfed by its value as residential space. Campion estimates that about 375 undergraduates currently live in fraternity houses. Since the concern for an egalitarian common dining hall has lessened, fraternity members can also cook their meals in the houses. The current Hanover assessment of the value of all fraternity property is roughly $2.7 million. "There has always been a paranoia among fraternity undergraduates that the College will close down fraternities," notes Campion. "But in truth the College couldn't afford to."

Neither can Dartmouth afford to allow such valuable property to depreciate so alarmingly. The College currently owns one house, the Alpha Chi Alpha building (assessed at $111,000), and maintains it as landlord. Alpha Chi has not been forced to submit to College control of their social activities, but recently they were able to build an addition with the College's financial backing. Dealing with Dartmouth was, in this case, much easier than appealing to a house corporation or taking out a second mortgage at a bank. These clearly are advantages to the College ownership of fraternity properties on a system-wide basis. David Kalapos of Alpha Chi Alpha states that "the College makes certain that the house stays in shape here — they have to because they own it."

With dormitory space at a premium, the beds offered by the fraternities provide needed relief to the crowded College facilities. If a significant number of fraternities became uninhabitable, the College would probably have to build more dormitories in the long run, since the dorms are now filled to capacity each fall and winter and private housing in the Hanover area is limited. But the cost per bed of dormitory construction ranges from $12,000 to $15,000. The newest dormitory, Channing-Cox, cost $15,000 per bed to build. With these disagreeable costs Dartmouth administrators would prefer not to; have to build anew. Given the need for fraternity bed space, any long-term trends towards physical decay would undoubtedly result in some sort of intervention. Campion, Woods, and Kalapos all see this intervention as virtually inevitable.

As a result of the broad concern for the physical and financial condition of the fraternities, along with past misunderstandings over the relationship between the College and the fraternities, there has been an attempt to redefine the fraternity system at Dartmouth. In September 1976, the Trustees established the Fraternity Study Group to examine "the legal and financial obligations which the fraternities and the College share with one another." The study concluded that "a necessary prerequisite to the effective analysis and solution of the complex combination of problems besetting the fraternity system at Dartmouth is the adoption of a basic document which clearly delineates the relationships among the fraternities and the College and establishes a governance structure for the fraternity system." It also recommended that the College assume responsibility for the maintenance of fraternity facilities and their business affairs, which would entail an estimated annual outlay in excess of $50,000.

The starting point is, of course, the idea of a constitution. Both the fraternities — as expressed by their representatives on the study committee and the Fraternity Governing Board — and the administra- tion agree on the need for a document establishing their formal relationship. Dean Hakanen, whose primary area of responsibility is the fraternities, claims that Dartmouth has felt powerless to effect needed reforms in individual houses because of the ambiguous nature of the College-fraternity relationship. He sees the main purpose of the proposed constitution as clarification, an explication of "who has the power to do what and when." Dean Manuel knows who has the power: "The Trustees, if they chose to do so, could kick the fraternities off campus next Monday." But the prevalent vagueness about mutual responsibilities and misconceptions about fraternity autonomy bother him. "The power to crack down," Manuel acknowledges, "that's what this is all about."

Most College officials, Manuel included, do not foresee large-scale intervention in the internal affairs of the fraternities, though some houses see things in a more gloomy light. "What happens in those houses is up to them," says Manuel. "But we plan to make sure that all the needed improvements get done." He suggests that the College, banks, and even the national fraternity organizations with local chapters could provide the funds needed for capital improvements, while each fraternity would be involved in the planning and execution of their renovations. Hakanen believes that fraternity distress over the constitution results from "paranoia about the control the College wants to exercise — they fear desires that no one has." He insists that the Trustees want to regulate the upkeep of the houses, not their activities. Ron Campion puts it another way: "Someone else can look out for their souls, I'll take care of the plumbing." The dean of students, John Hanson '59, also believes fraternity fears to be unwarranted. "The constitution," he says, "is just a reminder to the fraternities that they are only a part of the College."

Despite these assurances some fraternity members look askance at the current College initiative toward greater control. Craig Woods believes that the system is in the process of remedying its own problems. According to Woods, "anarchy reigned" in the Interfraternity Council as recently as four years ago. But he now detects a more serious effort toward self-regulation — something which is undoubtedly of pedagogical value to the students involved and might be lost under a more paternalistic structure. Woods fears that "eventually our autonomy may be impinged upon. The present draft of the constitution is worded too vaguely - which makes it possible to put too much power in the hands of the dean and the vice president for administration."

The proposed constitution is not a precise document, which is one of the criticisms frequently made by fraternity

members. Its basic doctrine is that fraternities are part of the College and thus must be subject to College control. Certain benefits are guaranteed, such as the assistance of Dartmouth in financial matters, security, and contacting fraternity alumni for fund-raising purposes. On the other hand, the fraternities are obligated to keep up their buildings according to certain standards (which remain to be es- tablished) and submit to whatever future rules are deemed necessary by the College and a newly created board of overseers. The constitution merely establishes a framework for regulation, it does not attempt to codify.

Perhaps the concern of the fraternities has been overstated. Manuel regards the recent claims of fraternity autonomy to be completely fictional. "People assume a degree of independence which is not a reality," he states. "If they [the houses] do something that is antithetical to the purpose of the College, we will exert our authority." Assurances have been made that fraternity life will be allowed to continue uninhibited under the new rules. But few people truly believe that major changes do not loom on the horizon. While Manuel does not advocate active intervention in the social life of fraternities, he makes no secret of his concern over certain aspects of this activity. "I'm concerned about the degree of alcohol consumption on this campus," he admits. "I think it's the most dangerous drug problem we

have." Manuel is also critical of certain attitudes he has encountered on "the Row." "I'd like to see some of the fraternities take a broader perspective," he says. Hakanen points to the unreported physical damage to property resulting from what he terms "rambunctiousness," and notes that the College has had difficulty controlling it. But Woods claims that fraternity members are not responsible for most of the damage. "Who would want to tear up his own house?" he asks. "We have to live there." Regardless of the perpetrators, such offenses will probably be more carefully watched in the near future.

There will quite probably be other changes as well, including a uniform raise in the room rents charged by fraternities and a ceiling on the number of members in each house. Manuel notes that a limit of 65 members is on the books of the College, but this restriction has been completely forgotten in the last decade. As a result of the unrestricted membership, certain fraternities have greatly prospered while others are on the verge of collapse for the lack of members. Alpha Chi Alpha, the largest house, now has 103 members, and others are not far behind. On the other hand houses like Phi Tau, Phi Psi, Gamma Delta, Tabard, and Alpha Theta all have significantly fewer than 50 members, and struggle each rush. Manuel feels that "103 is not a good number." At present about 50 per cent of the male undergraduates join fraternities, an increase from the 40 per cent figure quoted for the late 1960s but hardly comparable to the 19505, when about three quarters of the undergraduates joined houses.

Manuel, Campion, and Hakanen feel that a ceiling on the size of fraternities will "spread the wealth" more evenly among all the fraternities. Their contention is that individuals unable to secure a bid to join a particular fraternity will then join houses where the rush is less competitive. But many current undergraduates scoff at the notion that someone not chosen for Kappa Sigma would then try a smaller house along the lines of Alpha Theta, for example. Different houses, as the administrators are quick to point out, offer widely divergent experiences. The "filtering down" effect of a membership limit remains a question mark, but the era of gargantuan houses will eventually pass.

THERE are other questions being raised about the role of fraternities at Dartmouth and their long-term future. The social character of these organizations is difficult to pinpoint, since "we have a heterogeneous system," as Manuel notes. Recent additions, such as the Sigma Kappa and Kappa Kappa Gamma sororities, have added a new dimension to campus life. Sigma Kappa was formed last year and is waiting for a house to become available, and Kappa Kappa Gamma will take its first group of women this spring. Cathy McGrath 'BO, a charter member of Sigma Kappa, thinks that the sorority alternative fills what was previously a void for women: "I think most women used to feel sort of left out when their male friends joined fraternities, especially during rush. Going to social events as a guest isn't the same as having your own place to belong to." Few believe the sororities to be a fad, though Dean of Students Hanson sees their sudden upsurge mainly as a conse- quence of the overall drive toward equal rights for women. As Dean Manuel notes, the survival of sororities "depends on what they do to provide a good experience for people here."

Most of the people involved in the fraternity system welcome new additions to the social scene. They feel, justifiably so, that they have been forced to entertain the entire College in the past. Part of their financial problem results from the fact that they "have been giving away what they should be selling," according to Manuel, by throwing parties that are generally open to the public. The new student center' in College Hall is expected to relieve some of the burden, but a shift in social focus away from Webster Avenue does not appear likely in the near future, as much as some College officials would like to see it happen. Karen Blank, dean of freshmen, points out that fraternities are often discussed in monolithic terms, when in fact there is a great variety of activities and attitudes associated with the system. Still, she wonders whether some fraternities engender the chauvinistic outlook still alive on campus. "I'm not really certain of what goes on at fraternities," she says, "but I have to wonder if they aren't a bit parochial." Blank also questions, along with many others — including undergraduate fraternity members themselves — whether the houses have become overly social in their emphasis, to the possible detriment of the intellectual and cultural growth of their members. Hanson goes one step further than Blank. "Some fraternities," he claims, "fail to recognize that there are women at Dartmouth. Shutting out 1,000 people from your opportunity for growth like that is very short-sighted on their part."

"Change," an English cleric said long ago, "is not made without inconvenience, even from worse to better." A new draft of the fraternity constitution has been unanimously approved by the Trustees and now awaits a vote of the house presidents. They are expected to ratify it, thus committing their organizations to a fairly binding contractual arrangement with the College. "I just wish we had gotten together two years ago and put something together ourselves, so we could have said to the administration, Look, we have our own system of control. Then we might have avoided the present situation," reflects Bruce Kaufman '78 of Sigma Nu Delta. But as Dean Hanson notes, "When a group does not police itself it creates a vacuum into which some bigger organization will step." That "bigger organization" has taken its step, and the long-term result for Dartmouth's fraternities is anyone's guess. Strangely enough, fraternities at Dartmouth evolved from literary societies formed to loan books and read poetry. Who knows what the future holds for them?

What's Happened in 20 Years

1958

Alpha Chi Rho (national)

Alpha Delta Phi (national)

Alpha Theta (local)

Beta Theta Pi (national)

Chi Phi (national)

Delta Kappa Epsilon (national)

Delta Tau Delta (national)

Delta Upsilon (national)

Gamma Delta Chi (local)

Kappa Kappa Kappa (local)

Kappa Sigma (national)

Phi Delta Theta (national)

Phi Gamma Delta (national)

Phi Kappa Psi (national)

Phi Tau (local)

Pi Lambda Phi (national)

Psi Upsilon (national)

Sigma Alpha Epsilon (national)

Sigma Chi (national)

Sigma Nu (national)

Sigma Phi Epsilon (national)

Tau Epsilon Phi (local)

Theta Delta Chi (national)

Zeta Psi (national)

1978

Alpha Chi Alpha (local)

Alpha Delta (local)

Unchanged

Unchanged

Heorot (local)

Defunct

Bones Gate (local)

Foley House (local)

Unchanged

Unchanged

Unchanged

Phi Delta Alpha (local)

Defunct

Phi Sigma Psi (local)

Unchanged

Defunct

Unchanged

Unchanged

Tabard (local)

Sigma Nu Delta (local)

Sigma Theta Epsilon (local)

Harold Parmington Foundation (local)

Unchanged

Unchanged

Sigma Kappa (national sorority)

Kappa Kappa Gamma (national sorority)

Alpha Phi Alpha (local)

Mark Hansen '78, one of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE'S undergraduate editors, hasbelonged to a fraternity for three years.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMuddling Through Mud Season

April 1978 By Steven L. Calvert -

Feature

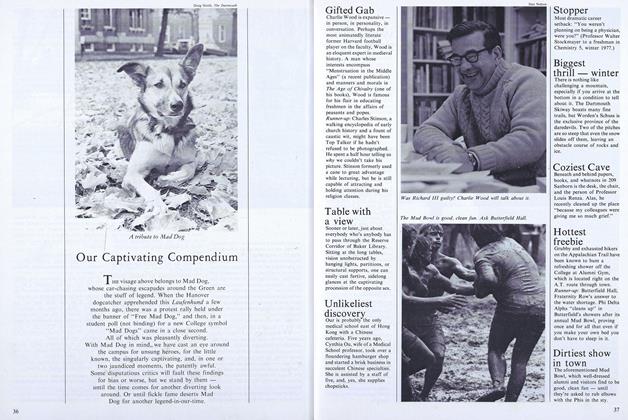

FeatureOur Captivating Compendium

April 1978 -

Feature

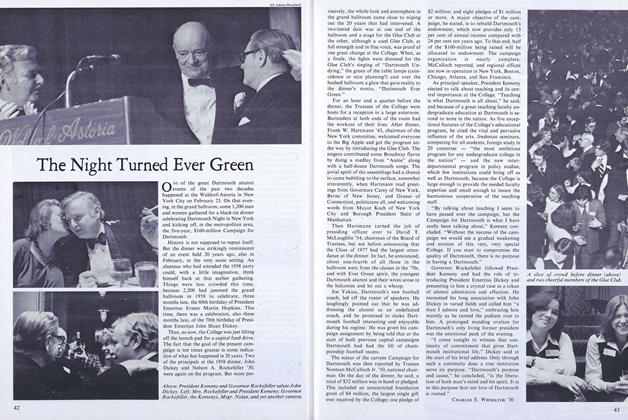

FeatureThe Night Turned Ever Green

April 1978 By CHARLES E. WIDMAYER '30 -

Article

ArticleAlchemist to the College

April 1978 By S.G. -

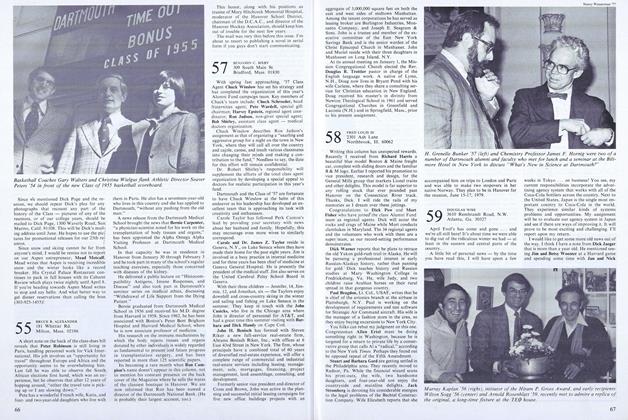

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

April 1978 By DOUGLAS WISE -

Article

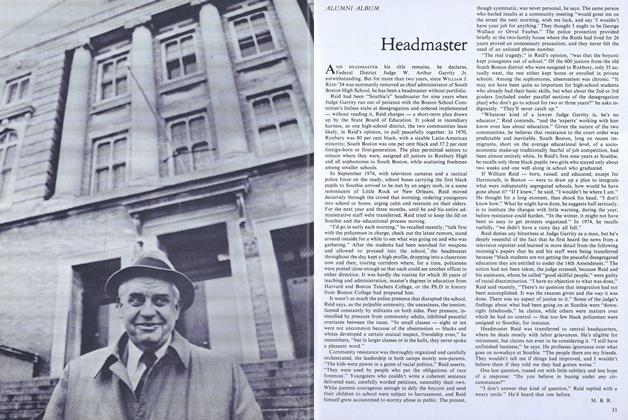

ArticleHeadmaster

April 1978 By M.B.R

Features

-

Feature

FeatureOne Answer for India

APRIL 1971 -

Feature

FeatureCoeducation

April 1975 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDinesh D'Souza '83

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureCoeducation Becomes A Reality

OCTOBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFragments of papyrus

DECEMBER • 1985 By RICHARD W. STERLING -

Features

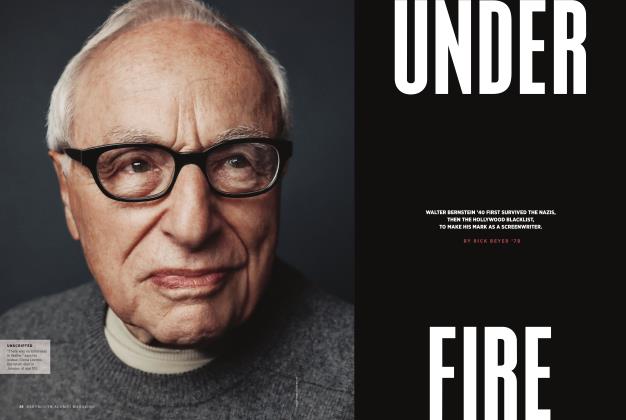

FeaturesUnder Fire

JULY | AUGUST 2021 By RICK BEYER '78