From his roots in the zinc mines of Galena, Illinois, Jim Wright gets a chance to show his depth.

WHEN THE CALL finally came, Jim Wright was sitting in the basement of his hilltop Etna home, doing taxes. The tax return distracted him. He expected Dartmouth's Trustees to end their national six-month search for the College's 16th president sometime that day, April 5. He knew the scope of the search, knew about the trend in higher education toward hiring professional fundraisers, knew that top schools generally looked outside their walls for candidates with national names and reputations. Jim Wright was the academic equivalent of the company man, a professor who'd been around forever and who had worked his way up through the ranks of the administration. The longer the search had dragged on, the more apprehensive Wright had grown about his chances.

After hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars in consulting fees, though, the search couldn't have ended closer to home. "Sometimes," said Bill King '63, chair of the search committee, "you need the national search to validate the internal choice as the best one." Trustee chairman Stephen Bosworth '61 phoned just before lunchtime, and, just as he had done many times at Dartmouth over the past 30 years, Jim Wright answered the call.

At a packed faculty meeting the following day in Alumni Hall, the Dartmouth community stood and cheered the announcement. At least part of the applause may have come from relief. Wright had been caught recently in the middle of a botched appointment to the position of provost. President James Freedman had named him to the post without following established procedure. To protect Freedman from a potentially ugly battle over the matter, Wright had decided to step aside. A lot of people felt the administration had lost a good man. Wright, uninterested in the presidency of any other institution, made plans to finish out his career in the classroom. Now, here he stood beaming, accepting the one challenge left for him at Dartmouth.

Few people in the College's modem era have been as deeply involved in its operation. Wright has taught in the history department, has chaired important committees, served as associate dean of the faculty, dean of the faculty, acting provost, provost, and, during James Freedman's 1995 sabbatical, acting president. Unlike many administrators he has gotten his hands dirty with the details; he runs his own numbers. He's gotten a feel not only for students and policy but for the budget and physical plant, as well. "This is someone," says colleague David Lagomarsino, "who knows where the load-bearing walls are."

One could outline Wright's service to Dartmouth by simply publishing his vita. But the vita could be mistaken for the dull rise of some gray-suited career bureaucrat. (Wright even recently bought a gray suit, and looks the part: a large, stolid man who seems soft until you shake his hand.) The vita tells only a part of Jim Wright's story.

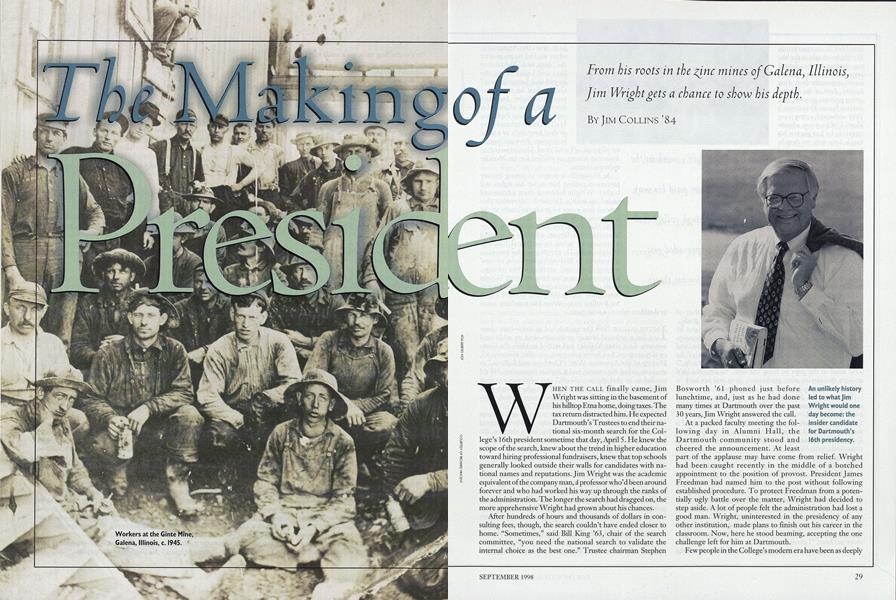

BY THE 1950s, the last of the lead mines around Galena, Illinois now working the deeper zinc deposits were playing out, and the town was a stagnant backwater of just a few thousand people. Wright's grandfather and namesake worked in the mines; neither of Wright's grandfathers had made it beyond the eighth grade.

All indifferent student in high school, Wright got by only because he was a good reader and had a great memory. He stood a head taller than many of his classmates, and played center on the football team. ("Unfortunately," he says, "bigness was no real advantage in the classroom.") Like most of the guys he hung out with, he assumed he'd go into the service after graduation, then end up back in Galena in a factory job or in one of the mines.

He joined the Marine Corps at age 17, having never traveled farther than the 160 miles east to Chicago. As part of a Marine Air Group, though, Wright was stationed in California, Hawaii, and Japan. In Japan he developed a fondness for haiku poetry and sushi. (Years later, on Dartmouth business, David Lagomarsino would travel extensively with Wright. "The first item on the agenda," says Lagomarsino, "was to find the best sushi in town.")

His sights lifted, Wright returned to Galena and enrolled at the University of Wisconsin, Platteville, a regional university just across the state line, with thoughts of becoming a high school teacher. He commuted from home. He married. Tuition ran $160 a semester, and Wright says he "worked like hell to pay for that"—as a janitor, bartender, laborer in a cheese factory. In the summer he signed on with the Eagle Pitcher Mining Co. and ran a machine that drilled holes for dynamite charges. He switched to powderman for 20 cents more per hour. "I guess people thought detonating the explosives was dangerous," Wright says. "Actually, the dangerous part was the trimming, when we had to go in after the blasts with 20-foot iron bars and knock down the jagged and hanging rock." Once when he was trimming, Wright. knocked down the hunk of lead that sits on his desk in Parkhurst Hall. On weekends he worked long shifts as a night watchman. Between rounds he slipped off and read Shakespeare or American history or studied for his Monday morning classes.

At Platteville a couple of young history professors pushed him to set his sights still higher. Wright followed their advice and ended up with a Danforth fellowship that funded five years of graduate study at the University of Wisconsin.

At Madison Wright discovered a mentor, historian Allan Bogue, who was pioneering quantitative work in political history. Wright's Ph.D. thesis, on the populist movement in Colorado, analyzed miners' voting patterns, among other things. Occasionally, as a teaching assistant, Wright took over Bogue's history class. Bogue remembers seeing Wright in front of a class for the first time it was like watching a natural athlete take to a new sport.

IN THE FALL OF 1968 Dartmouth had an immediate opening for a political history professor and an additional concern. Ever since Al Foley had retired in 1964, the history department had been reluctant to offer History 57, History of the American West. "Cowboys and Indians," as students called the course, had a mythic reputation. "We'd needed to let that course cool off," says professor emeritus Charles Wood. By October of '68, though, enough time had passed. "What we needed now," says Wood, "was someone who could really teach the West."

Jim Wright had a background in political and western U.S. history, and a third credential, too. Newly-appointed president John Kemeny had made his views clear on the importance of the computer as a research tool. For his dissertation Wright had used a computer extensively in cross-tabulating the Colorado miners' voting behavior. "He recognized that the data were simply a starting point," says Wood, a member of the interviewing team. "He was, by far, the most sophisticated of the people we saw who were quantifying history."

Wright accepted the sure offer from Dartmouth, for going interviews at Princeton and Michigan. He took on "Cowboys and Indians," upon the urging of department chairman Lou Morton. (Wright initially felt uneasy about teaching outside of his niche, but the course soon became oversubscribed and remained one of the most popular classes at Dartmouth for the 15 years Wright taught it.) The relationship with Lou Morton turned out to be pivotal. While Wright continued teaching and writing (he won a Guggenheim in 1973, rare enough at Dartmouth but doubly rare to win one, as Wright did, before even gaining tenure), Morton recognized Wright's ability to manage and lead people. A military historian, Morton took Wright under his command. "Though I didn't realize it then," Wright says, "Lou was giving me mini-seminars on how things worked around here. I learned much about the Dartmouth landscape from him."

Wright's move into administration came in 1978 as chair of the Committee on the Curriculum and Year-round Education, a huge committee with the near-impossible charge of evaluating the D-Plan's effect on the quality and structure of Dartmouth's academic program. "That committee report was near-unanimous, which is almost unheard of," says Hans Penner, who later tapped Wright to be an associate dean of the faculty. "That spoke volumes about Jim." Penner and others talk about the traits that marked Jim Wright's work: fairness, patience, discretion, optimism, wry humor, ability to keep the big picture in focus, to delegate and give subordinates ates their rein and a striking sense of civility that allows him to engage his peers on any topic, no matter how charged or sensitive. Early on Wright lobbied for a Native American Studies department and, later, for a revised alma mater. He shepherded the College's first new curriculum in 70 years through the intellectual-and-turf-and-ego minefield of the faculty. He recently defended the controversial design of the planned Berry Library. "I like it," he said simply." "And that and 50 cents will buy you a cup of coffee."

In the weeks following the presidential announcement, Jim Wright stories filtered through the Dartmouth community: Professor Wright working late in the office over Thanksgiving weekend; Dean Wright keeping a stack of parking tickets on his desk to show complaining faculty that he was with them, not above them; fundraiser Wright earning premier status on three different airlines during the last two years of the College's recent capital campaign. ("He was—on campus absolutely the engine that drove that campaign," says Lu Martin, who headed the effort for three years. The Arts & Sciences endowment more than doubled during Wright's years as dean.) There were stories of Acting President Wright speaking powerfully about war, death, and remembrance at a class officers' dinner, yet not letting on about his own wrenching worry for his wife Susan's breast cancer. Stories of Wright keeping a file of every student he ever taught and what grades he gave them and looking them up when he was on the road; stories about personal loyalty, his appetites for food and gardening and reading, and about his extraordinary memory. (Recalling how surprised he was when Wright tapped him to be associate dean of faculty, David Lagomarsino says, "Years ago, on a flight back from London, over a particularly bad airline martini, Jim asked if I had any interest in going into the administration. His question and my answer took all of 12 seconds—but he remembered.") The presidential search committee, looking at such a known quantity, had far more than a vita to go on.

IN RECENT HISTORY Dartmouth presidents appear to have been chosen to counterbalance the traits of their predecessors. Wright says he doesn't come to the office with that sense of remediation. Many of the initiatives of the Freedman era, in fact, can be traced somehow to the work of Jim Wright; some of the threads in the new curriculum, for example, stretch back more than 20 years. "It seems to me," says Hans Penner, "that Jim Freedman put together a glove that fits Wright's hand beautifully." In his acceptance speech, Wright didn't present a new agenda for the College. He said that will come in time. Instead, he voiced the areas of his biggest concern: the importance of Dartmouth remaining a top-notch research university, a commitment to diversity, a commitment to affirmative action. He spoke of the College being a community of learners. He chose his words consciously, inviting debate head-on.

His 15-minute acceptance speech may have said something important about the ways this presidency will differ from James Freedman's, in style if not in substance. He led with low-brow humor, a quote from Yogi Berra. ("When you come to a fork in the road, take it.") He referred to his wife Susan, whose work counseling Dartmouth undergraduates over the past 20 years will provide a valuable perspective in the new administration. He grounded his speech in Dartmouth's history. He talked about his roots in Galena.

"I know well the distance from there to this spot for this occasion," he said. "I recognize personally the power of education and the capacity of institutions like Dartmouth, at their best, to enable full opportunities and rich lives...."

Questions raised by the hiring of an internal candidate the implicit endorsement of the status quo, the message that Dartmouth doesn't need to look outside for fresh ideas or innovation—seemed far away. A more immediate question loomed. Where does Wright have his sights set, now? We'll find out beginning with his inauguration on September 23.m

Workers at the Ginte Mine, Galena, Illinois, c. 1945.

An unlikely history led to what Jim Wright would one day become: the insider candidate for Dartmouth's 16th presidency.

Wright's work in the mines paid his way through college and provided grit for his thesis.

"I know well the distance from there to this spot. I recognise the power of education."

JIM COLLINS '84 is the acting editor of this magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

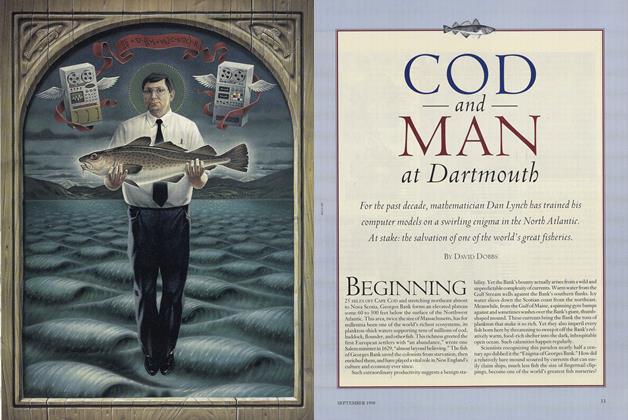

FeatureCOD and MAN at Dartmouth

September 1998 By David Dobbs -

Feature

FeatureFOR REAL

September 1998 By Jana M. Friedman '94 -

Feature

FeatureFrom Rap to Ritual

September 1998 By Everett Wood '38 -

Article

ArticleFour Aces

September 1998 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleThe Origin of Endangered Species

September 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleA Soggy Commencement

September 1998

Jim Collins '84

-

Cover Story

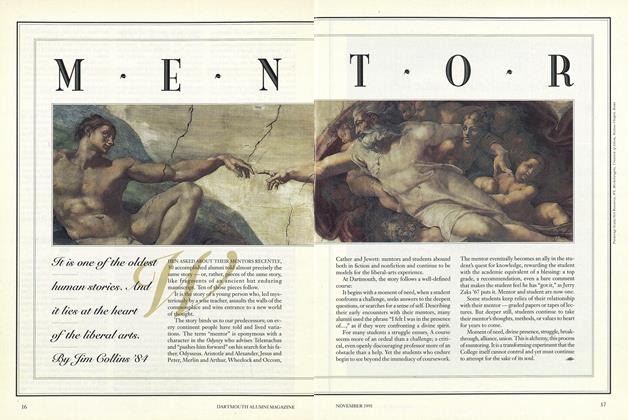

Cover StoryMENTOR

NOVEMBER 1991 By Jim Collins '84 -

Article

ArticleThe Lost Season

October 1992 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Article

ArticleThe Role of an Intellectual

JANUARY 1998 By Jim Collins '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryANDREW WEIBRECHT '09

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

PURSUITS

PURSUITSArt of Glass

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2020 By Jim Collins '84 -

FEATURES

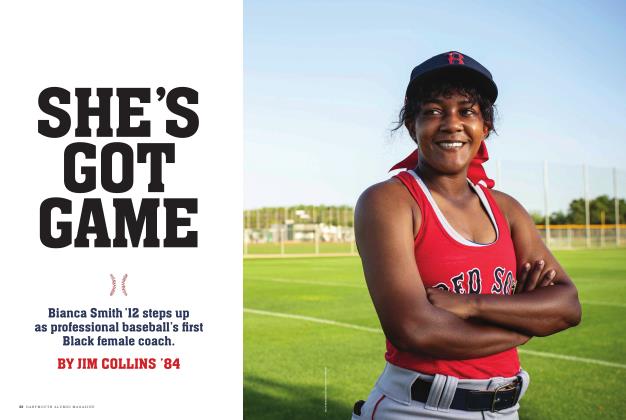

FEATURESShe’s Got Game

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2021 By JIM COLLINS '84

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Official Dartmouth Reunion Guide to Greenspeak

MAY • 1987 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Man for All Seasons

NOVEMBER • 1985 By Douglas McCreary Greenwood '66 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Balance

MAY 1997 By James Wright -

FEATURES

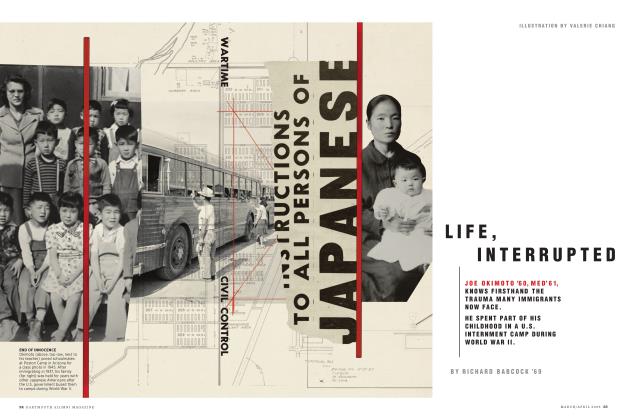

FEATURESLife, Interrupted

APRIL 2025 By RICHARD BABCOCK ’69 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Price Glory?

OCTOBER • 1987 By Ted Leland