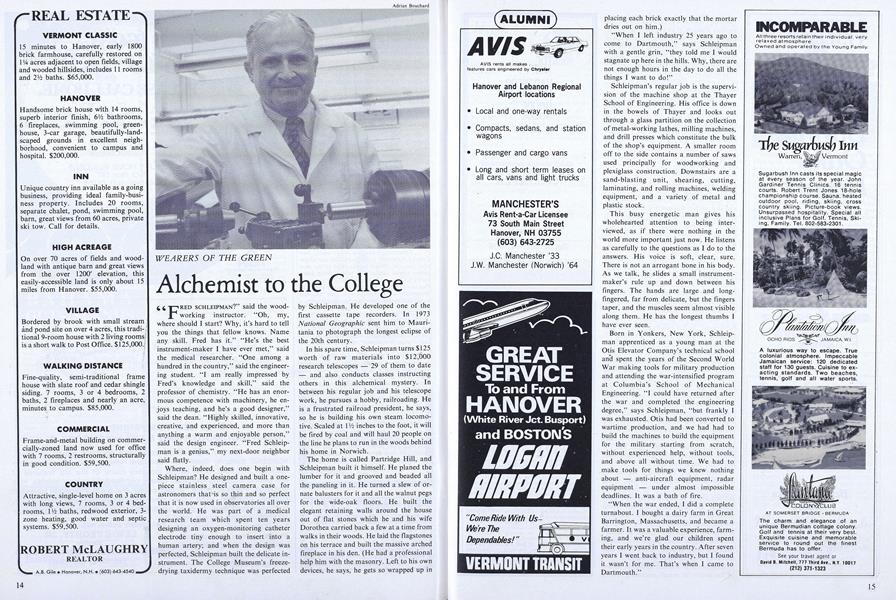

FRED SCHLEIPMAN?" said the woodworking instructor. "Oh, my, where should I start? Why, it's hard to tell you the things that fellow knows. Name any skill. Fred has it." "He's the best instrument-maker I have ever met," said the medical researcher. "One among a hundred in the country," said the engineering student. "I am really impressed by Fred's knowledge and skill," said the professor of chemistry. "He has an enormous competence with machinery, he enjoys teaching, and he's a good designer," said the dean. "Highly skilled, innovative, creative, and experienced, and more than anything a warm and enjoyable person," said the design engineer. "Fred Schleipman is a genius," my next-door neighbor said flatly.

Where, indeed, does one begin with Schleipman? He designed and built a onepiece stainless steel camera case for astronomers that is so thin and so perfect that it is now used in observatories all over the world. He was part of a medical research team which spent ten years designing an oxygen-monitoring catheter electrode tiny enough to insert into a human artery; and when the design was perfected, Schleipman built the delicate instrument. The College Museum's freezedrying taxidermy technique was perfected by Schleipman. He developed one of the first cassette tape recorders. In 1973 National Geographic sent him to Mauritania to photograph the longest eclipse of the 20th century.

In his spare time, Schleipman turns $125 worth of raw materials into $12,000 research telescopes — 29 of them to date — and also conducts classes instructing others in this alchemical mystery. In between his regular job and his telescope work, he pursues a hobby, railroading. He is a frustrated railroad president, he says, so he is building his own steam locomotive. Scaled at 1½ inches to the foot, it will be fired by coal and will haul 20 people on the line he plans to run in the woods behind his home in Norwich.

The home is called Partridge Hill, and Schleipman built it himself. He planed the lumber for it and grooved and beaded all the paneling in it. He turned a slew of ornate balusters for it and all the walnut pegs for the wide-oak floors. He built the elegant retaining walls around the house out of flat stones which he and his wife Dorothea carried back a few at a time from walks in their woods. He laid the flagstones on his terrace and built the massive arched fireplace in his den. (He had a professional help him with the masonry. Left to his own devices, he says, he gets so wrapped up in placing each brick exactly that the mortar dries out on him.)

"When I left industry 25 years ago to come to Dartmouth," says Schleipman with a gentle grin, "they told me I would stagnate up here in the hills. Why, there are not enough hours in the day to do all the things I want to do!"

Schleipman's regular job is the supervision of the machine shop at the Thayer School of Engineering. His office is down in the bowels of Thayer and looks out through a glass partition on the collection of metal-working lathes, milling machines, and drill presses which constitute the bulk of the shop's equipment. A smaller room off to the side contains a number of saws used principally for woodworking and plexiglass construction. Downstairs are a sand-blasting unit, shearing, cutting, laminating, and rolling machines, welding equipment, and a variety of metal and plastic stock.

This busy energetic man gives his wholehearted attention to being interviewed, as if there were nothing in the world more important just now. He listens as carefully to the questions as I do to the answers. His voice is soft, clear, sure. There is not an arrogant bone in his body. As we talk, he slides a small instrumentmaker's rule up and down between his fingers. The hands are large and long-fingered, far from delicate, but the fingers taper, and the muscles seem almost visible along them. He has the longest thumbs I have ever seen.

Born in Yonkers, New York, Schleipman apprenticed as a young man at the Otis Elevator Company's technical school and spent the years of the Second World War making tools for military production and attending the war-intensified program at Columbia's School of Mechanical Engineering. "I could have returned after the war and completed the engineering degree," says Schleipman, "but frankly I was exhausted. Otis had been converted to wartime production, and we had had to build the machines to build the equipment for the military starting from scratch, without experienced help, without tools, and above all without time. We had to make tools for things we knew nothing about — anti-aircraft equipment, radar equipment — under almost impossible deadlines. It was a bath of fire.

"When the war ended, I did a complete turnabout. I bought a dairy farm in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, and became a farmer. It was a valuable experience, farming, and we're glad our children spent their early years in the country. After seven years I went back to industry, but I found it wasn't for me. That's when I came to Dartmouth."

Schleipman left a position as head of the machine division of an engineering firm in Connecticut. "It was a good job, and it was very good money," he recalls. "But the internal politics were a mess, and it was a very materialistic society. We felt culturally starved there. I took a two-thirds cut in pay to come to Dartmouth. But you have to set your priorities."

His first position at Dartmouth was as instrument-maker to the Physics Department, where he spent 14 years. But the shop there was open only to faculty, and Schleipman found he wanted more contact with students. When the Thayer position, with its half-time teaching responsibilities, opened up in 1969, he took it. "Teaching is the plus in my job," he says. "It means more to me than the salary ever has."

At Thayer he works with students and faculty in the design and construction of thesis, classroom, and research equipment and also teaches Engineering 3, Metal Processing. In this course, each student constructs a Sterling two-cycle hot-air engine, starting from rough castings and making use of every machine in the shop.

"I'm not trying to turn out machinists with the course," explains Schleipman, "but I do want the engineers to be aware of the capacities and the limitations of machinery, so that their designs reflect them. They should get a feeling for the time machining takes, too, so that they can estimate costs realistically."

If his students have meant a lot to Schleipman, he has also meant a great deal to many of them. Frederic Chaffee '63, resident astronomer at the Smithsonian's Mt. Hopkins Observatory in Tucson, says that it was Schleipman's telescope-making classes which led him to switch from physics to astronomy. "The striking thing about Fred Schleipman," Chaffee explains, "is the extraordinary care he takes with everything he does. That's very rare in the physical sciences today, where slapdash experiments are the rule. What impressed me most was that when you designed an experiment with Fred Schleipman, it designed properly to begin with, and the results would hold up for a long time. That has really stuck with me."

Award-winning mechanical engineering student Stephen Wyckoff '78 says of his teacher Schleipman, "He is the kindest, gentlest man I've ever worked with. Considering his demanding attitude about precision and cleanliness, his tolerance toward those who don't share his standards is amazing. I think that because he doesn't have the degree many people tend not to treat him as an engineer. But I would take him over any professor at Thayer."

Schleipman is worried about the future of his course in metal processing. He is leaving Dartmouth this month, taking early retirement to set up his own company, and there are signs that Thayer is deemphasizing the mechanical end of engineering. Schleipman and others fear that the machine course will be dropped. Once required of all engineering students, the course some time ago became an elective because of a lack of staff and of space to accommodate the enlarged student body. Last year a severe shortage of staff in the machine shop made it impossible for Schleipman to offer the course at all.

"The course is expensive, and the current deans are more theoretically than mechanically minded," explains Schleipman. "Thayer is now teaching management engineers, not hands-on engineers." He hastens to add that there is no more well-trained, profit-minded management engineer than the one Thayer puts out, but he feels strongly that the lack of practical experience is bad. "You see the effect in refrigerators, vacuum cleaners, automobiles. Design decisions are not reflecting the basics any more. When you pick up the hood of a 1978 car, you can't even find the engine, let alone work on it. It's somewhere down there under hundreds of hoses and accessories and wiring harnesses."

Thayer's Dean Carl Long agrees that there is "something to be learned from converting paper to fact," but he explains that the explosion of scientific knowledge has led many engineering educators to feel that time in school is best invested in acquiring a broad theoretical base. "We will make the machine course available to the students as long as we find they want it. If it looks as though they and we are wasting our time," he says, "we'll drop it."

"It hurts me," says Schleipman, thinking about leaving Dartmouth and about the trend away from hands-on training for engineers. "I think we're losing the right kind of engineer." But he is not one to linger over things he can't help. Changing the subject, he offers to show me the new $40,000 precision milling machine which is to form the mainstay of his new company, Precision Masters, Inc.

"It's a big step, going on my own," he says as we walk down the hall. "But I couldn't see sitting around getting stale for the next seven years until retirement. Anyway, I plan to keep in contact with Dartmouth. We have made many wonderful friends'there. And our doors will always be open to the students. I hope they'll make use of the chance to see industry in operation. Besides," he adds happily, "living in this area is in itself a liberal education. There are so many experts in and around Hanover, so many interesting people."

There certainly are.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAn Unease on Webster Avenue

April 1978 By Mark Hansen -

Feature

FeatureMuddling Through Mud Season

April 1978 By Steven L. Calvert -

Feature

FeatureOur Captivating Compendium

April 1978 -

Feature

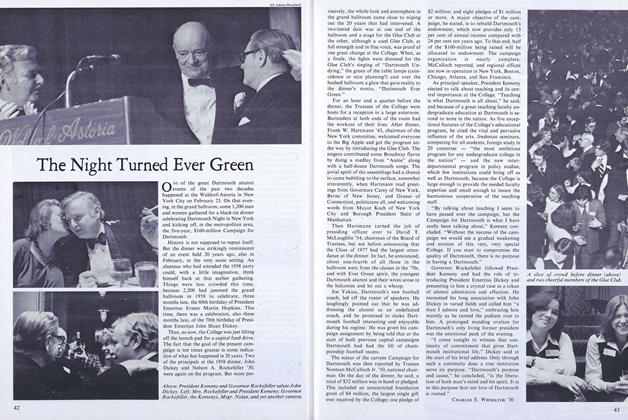

FeatureThe Night Turned Ever Green

April 1978 By CHARLES E. WIDMAYER '30 -

Class Notes

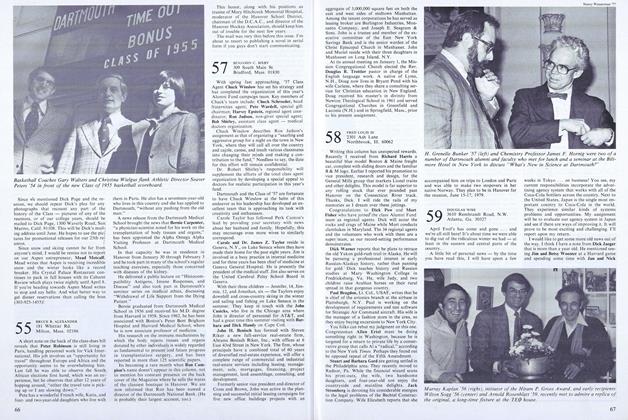

Class Notes1959

April 1978 By DOUGLAS WISE -

Article

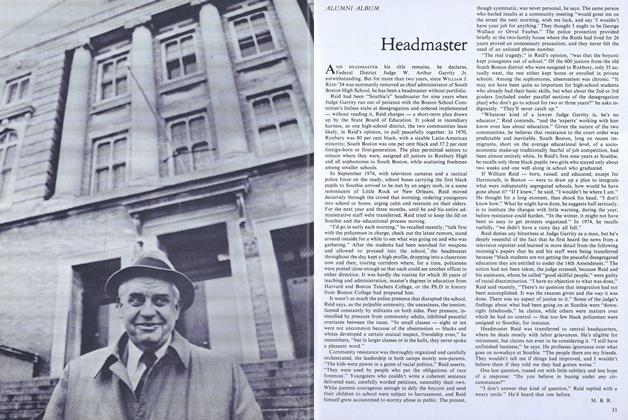

ArticleHeadmaster

April 1978 By M.B.R

S.G.

-

Article

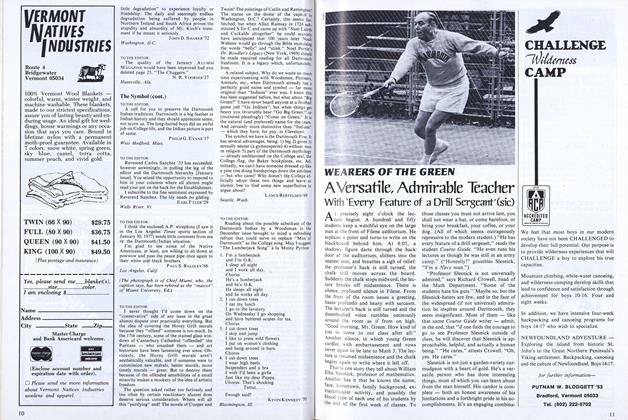

ArticleA Versatile, Admirable Teacher With "Every Feature of a Drill Sergeant'(sic)

March 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleThe Call Heard Round the World

OCT. 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleDick's House Is Her House

NOV. 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleResident Rotiferologist

DEC. 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleOf God, Man, and Mountains

JAN./FEB. 1978 By S.G. -

Feature

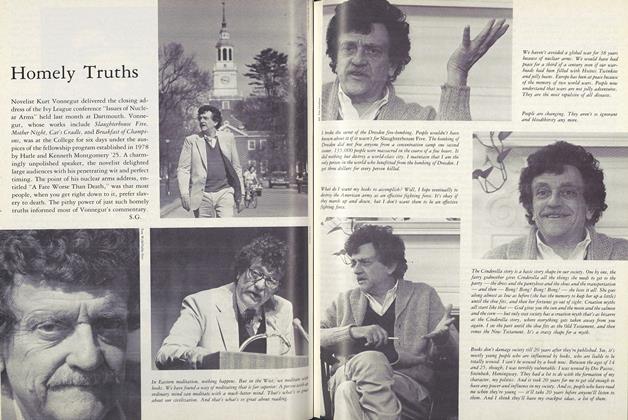

FeatureHomely Truths

JUNE 1983 By S.G.

Article

-

Article

ArticleProfessor Woods' study of the vocational

February 1918 -

Article

ArticleRequired Reading

NOVEMBER 1996 -

Article

ArticleEngineering: Believe it!

JUNE 1998 -

Article

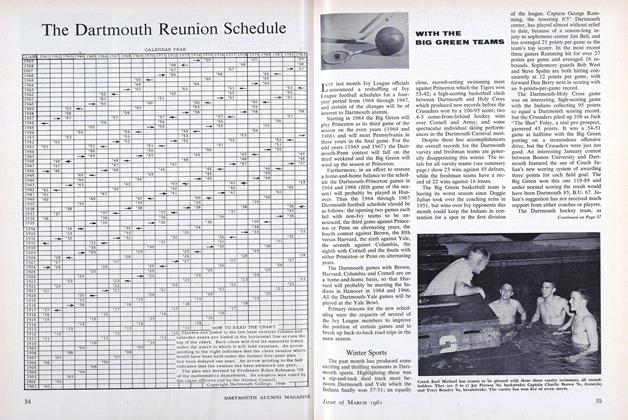

ArticleWinter Sports

March 1961 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleThe 21st Carnival

MARCH 1931 By Craig Thorn, Jr. -

Article

ArticleBeyond Good Ground

May 1979 By GREGORY RABASSA '44