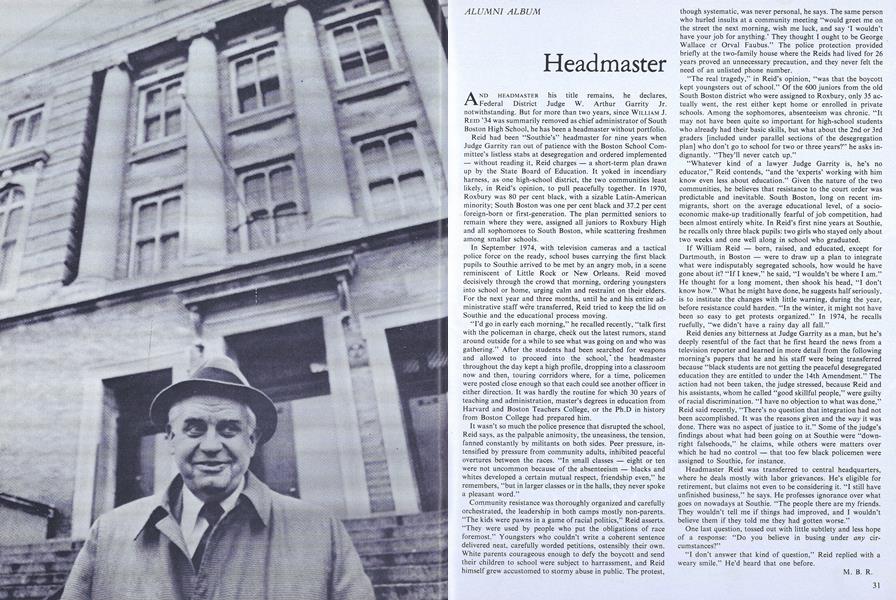

AND HEADMASTER his title remains, he declares, Federal District Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr. notwithstanding. But for more than two years, since WILLIAM J. REID '34 was summarily removed as chief administrator of South Boston High School, he has been a headmaster without portfolio.

Reid had been "Southie's" headmaster for nine years when Judge Garrity ran out of patience with the Boston School Committee's listless stabs at desegregation and ordered implemented — without reading it, Reid charges — a short-term plan drawn up by the State Board of Education. It yoked in incendiary harness, as one high-school district, the two communities least likely, in Reid's opinion, to pull peacefully together. In 1970, Roxbury was 80 per cent black, with a sizable Latin-American minority; South Boston was one per cent black and 37.2 per cent foreign-born or first-generation. The plan permitted seniors to remain where they were, assigned all juniors to Roxbury High and all sophomores to South Boston, while scattering freshmen among smaller schools.

In September 1974, with television cameras and a tactical police force' on the ready, school buses carrying the first black pupils to Southie arrived to be met by an angry mob, in a scene reminiscent of Little Rock or New Orleans. Reid moved decisively through the crowd that morning, ordering youngsters into school or home, urging calm and restraint on their elders. For the next year and three months, until he and his entire administrative staff were transferred, Reid tried to keep the lid on Southie and the educational process moving.

"I'd go in early each morning," he recalled recently, "talk first with the policeman in charge, check out the latest rumors, stand around outside for a while to see what was going on and who was gathering." After the students had been searched for weapons and allowed to proceed into the school, the headmaster throughout the day kept a high profile, dropping into a classroom now and then, touring corridors where, for a time, policemen were posted close enough so that each could see another officer in either direction. It was hardly the routine for which 30 years of teaching and administration, master's degrees in education from Harvard and Boston Teachers College, or the Ph.D in history from Boston College had prepared him.

It wasn't so much the police presence that disrupted the school, Reid says, as the palpable animosity, the uneasiness, the tension, fanned constantly by militants on both sides. Peer pressure, in- tensified by pressure from community adults, inhibited peaceful overtures between the races. "In small classes — eight or ten were not uncommon because of the absenteeism — blacks and whites developed a certain mutual respect, friendship even," he remembers, "but in larger classes or in the halls, they never spoke a pleasant word."

Community resistance was thoroughly organized and'carefully orchestrated, the leadership in both camps mostly non-parents. "The kids were pawns in a game of racial politics," Reid asserts. "They were used by people who put the obligations of race foremost." Youngsters who couldn't write a coherent sentence delivered neat, carefully worded petitions, ostensibly their own. White parents courageous enough to defy the boycott and send their children to school were subject to harrassment, and Reid himself grew accustomed to stormy abuse in public. The protest, though systematic, was never personal, he says. The same person who hurled insults at a community meeting "would greet me on the street the next morning, wish me luck, and say 'I wouldn't have your job for anything.' They thought I ought to be George Wallace cr Orval Faubus." The police protection provided briefly at the two-family house where the Reids had lived for 26 years proved an unnecessary precaution, and they never felt the need of an unlisted phone number.

"The real tragedy," in Reid's opinion, "was that the boycott kept youngsters out of school." Of the 600 juniors from the old South Boston district who were assigned to Roxbury, only 35 actually went, the rest either kept home or enrolled in private schools. Among the sophomores, absenteeism was chronic. "It may not have been quite so important for high-school students who already had their basic skills, but what about the 2nd or 3rd graders [included under parallel sections of the desegregation plan] who don't go to school for two or three years?" he asks indignantly. "They'll never catch up."

"Whatever kind of a lawyer Judge Garrity is, he's no educator," Reid contends, "and the 'experts' working with him know even less about education." Given the nature of the two communities, he believes that resistance to the court order was predictable and inevitable. South Boston, long on recent immigrants, short on the average educational level, of a socio-economic make-up traditionally fearful of job competition, had been almost entirely white. In Reid's first nine years at Southie, he recalls only three black pupils: two girls who stayed only about two weeks and one well along in school who graduated.

If William Reid — born, raised, and educated, except for Dartmouth, in Boston — were to draw up a plan to integrate what were indisputably segregated schools, how would he have gone about it? "If I knew," he said, "I wouldn't be where I am." He thought for a long moment, then shook his head, "I don't know how." What he might have done, he suggests half seriously, is to institute the changes with little warning, during the year, before resistance could harden. "In the winter, it might not have been so easy to get protests organized." In 1974, he recalls ruefully, "we didn't have a rainy day all fall."

Reid denies any bitterness at Judge Garrity as a man, but he's deeply resentful of the fact that he first heard the news from a television reporter and learned in more detail from the following morning's papers that he and his staff were being transferred because "black students are not getting the peaceful desegregated education they are entitled to under the 14th Amendment." The action had not been taken, the judge stressed, because Reid and his assistants, whom he called "good skillful people," were guilty of racial discrimination. "I have no objection to what was done," Reid said recently, "There's no question that integration had not been accomplished. It was the reasons given and the way it was done. There was no aspect of justice to it." Some of the judge's findings about what had been going on at Southie were "down-right falsehoods," he claims, while others were matters over which he had no control — that too few black policemen were assigned to Southie, for instance.

Headmaster Reid was transferred to central headquarters, where he deals mostly with labor grievances. He's eligible for retirement, but claims not even to be considering it. "I still have unfinished business," he says. He professes ignorance over what goes on nowadays at Southie. "The people there are my friends. They wouldn't tell me if things had improved, and I wouldn't believe them if they told me they had gotten worse."

One last question, tossed out with little subtlety and less hope of a response: "Do you believe in busing under any circumstances?"

"I don't answer that kind of question," Reid replied with a weary smile." He'd heard that one before.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAn Unease on Webster Avenue

April 1978 By Mark Hansen -

Feature

FeatureMuddling Through Mud Season

April 1978 By Steven L. Calvert -

Feature

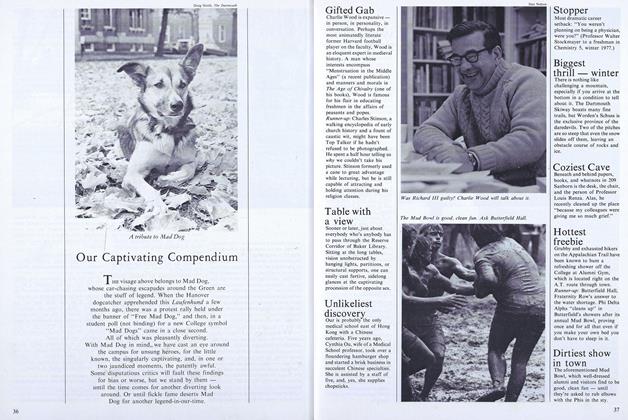

FeatureOur Captivating Compendium

April 1978 -

Feature

FeatureThe Night Turned Ever Green

April 1978 By CHARLES E. WIDMAYER '30 -

Article

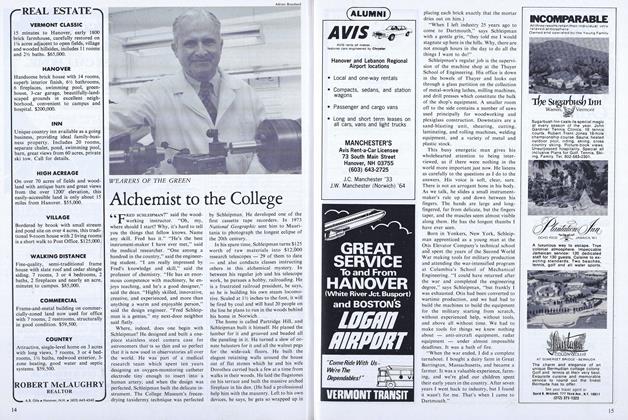

ArticleAlchemist to the College

April 1978 By S.G. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

April 1978 By DOUGLAS WISE