The Barbary Coast and the Green Serenaders,The Twenties and the Depression

JAZZ music rooted itself at Dartmouth around 1915 and blossomed in the 19205. It was fun to listen to and even more fun to dance to with the Girl of My Dreams or some Betty Co-Ed. The tunes and the lyrics were part of many students' education — first through the traditional medium of sheet music, then on phonograph records, and by the late 1920s through sponsored musical programs on radio. Finally, this popular music was entertaining all America via the new talking pictures from Hollywood. It was the Jazz Age.

Here's how it was in 1928 in Hanover. Students returning to college in September of that prosperous year were proudly aware of the new Baker Library and its tuneful clock-tower chimes. Also, the sound of band practice floating up from the gym area foretold the football season. An occasional snatch of recorded music issued from someone's dry-battery dorm radio, but most of the jazz came from the latest 78-rpm black-wax record on a student's wind-up Orthophonic portable or a fraternity's all-electric Brunswick Panatrope console.

Who in Hanover were the hard-core buffs of this dance music? A few dozen student musicians, plus a handful of others with jazz in their genes. Ed Lilley '28 commented recently about such folk: Musicians are a special breed, bound by a talent hard for others to understand. Some are so indelicate as to infer that we are a little kooky. Could be. But we make music to make people happy." Russ Goudey '29, reed man and leader of the Barbary Coast for 1928 and 1929, wrote: "We felt we were carrying on a tradition at the time, with great pride in our activity and the prestige which accompanied our considerable success and acceptance. We dedicated our performances as background for social dancing. We provided excitement."

A publicity blurb in Goudey's scrapbook described the Barbary Coast as a "Favorite child of the Goddess Syncopation. Contagious rhythm. Entertaining. Eleven instruments full of wild, harmonious, mad, exuberant music. With the help of this band we will all make whoopee in the dance immediately following the Musical Clubs concert."

Some of the Instrumental Club members of that time still think the jazz musicians were unduly high-hat and too full of their own importance. It makes one wonder if a football hero ever was envious of a jazzman.

Paul Freeman '30, banjo regular with the Barbary Coast for three years, remembered that as a freshman he had especially admired Ed Lilley, who played tenor sax with the Green Serenaders under the leadership of Ed Plumb. (Both men also were sometime Barbary Coasters.) Freeman wrote: "My most vivid memory of Lilley is as a comedian on a Musical Clubs trip. In a parody of a radio program, he announced, speaking through his saxophone: 'We will now present another episode of that great drama of the Golden West entitled Hoof Hearted.'' A few guffaws of appreciation always greeted this flatulent gag." Freeman remembered other outstanding student musicians:

Rollie Howes '28, banjo, had an excellent ear, a completely flexible and controllable wrist, and rhythmic ingenuity equaled at the time only by the jazz professional Carl Kress. The last time I heard Rollie was in a graduation-time concert in Webster Hall. He took a chorus on "Tiger Rag" and the audience burst into spontaneous applause.

Then there was Johnny Hahn '30. He was tall, quite handsome, a strictly wild character who played vigorous hot trumpet with the Coast (plus other instruments) and led and managed them my senior year.

I must also mention that brilliant young scholar Franklyn Marks '32, youngest in his class and the only member to get straight A's his first semester. Later, he was Phi Bete and Senior Fellow. Frank was a talented jazz pianist.

Another all-around good fellow and friend was Neal R. Dowe '28, better known as Nibs. He was all of five feet tall, but right away you noticed his jolly face. He was a constant source of humor and entertainment, played piano with the Coast prior to Marks, and piano in the Nugget during the year or so before movies spoke up. He couldn't play jazz, classical or swing - but was great on all popular music.

My roommate was the Coast drummer Jeff Jeffrey '30. Both he and I disliked the trend toward stock arrangements. It meant dragging music stands to a job.

Paul Weston '33 noted: "I thought the Barbary Coast was pretty keen, particularly since I wasn't good enough to play in it." Weston led the Green Serenaders, a student band whose members often interchanged with the Barbary Coast. Weston, of course, was plenty good enough to be piano man for the Barbary Coast, but that chair was already filled by Frank Marks. Bill Scherman '34 noted that Weston studied harmony at Dartmouth under Professors Whitford and Longhurst, won his Phi Beta Kappa key in junior year, got into professional piano playing and band arrangements in New York, and helped build such bands as those of Joe Haymes, Phil Harris, Rudy Vallee, Tommy — Dorsey and, according to Scherman, "from there to Hollywood, TV, and glory."

The Green Serenaders date from around 1922 and were organized by Joe Egolf'25, piano. Early regulars were Ken Christophe '24, violin, and Stu Edgerly '25, sax. Wat Dickerman '28, drums, reported that the 1928 band included Jack Brabb '29, trumpet, Don Childs '29, banjo, and Bruce Benson '29, piano. Frank Hodson '31, sax, singled out Benson as "an excellent piano player — with hands like hams — with which he banged out a mean bass." Hod- son noted that Jack Brabb was a good trumpet man who played with the Green Serenaders, and occasionally with the Coast. This switch-around was true of Hodson, too, though his main responsibility in his senior year was as leader of the Barbary Coast. He spelled out the interrelationship in a recent letter:

There were almost two Barbary Coasts. We booked our own dance jobs, set our own pay scales, and were free agents. The other set-up was when we played for and went on the Musical Clubs trips. All the Coast members were in the Instrumental Club and played in the concert with the Glee Club. After the concert, the Coast played for dancing, and were paid $2 per hour per man. [The jobs the Coast booked themselves netted rather higher compensation.] We used a few stock arrangements. Most scores were worked out on a one-chorus arrangement for harmony, and there was a great deal of ad lib.

RECORDS continued to be the useful link between limited campus listening to the Five sound and what the record industry sloganized as "the music you want to hear when you want to hear it." New records on the Victor label arrived at Allen's Drug Store at a rate of six per week. Ads in The Dartmouth invited students to "gather round the Orthophonic with the gang and .listen to George Olsen play his latest." That would be, perhaps, "Doin' the Raccoon or "Walking With Susie," both of which had sprightly melodies and memorable lyrics. (These same issues of the newspaper advertised an offer by local tailor Pat Kelly to make a free suit or overcoat for the man who scored the first touchdown against Yale. But the jinx prevailed. Dartmouth lost, 18-0.)

Bud's Smoke Shop, across Main Street, featured Columbia and Brunswick records and Dartmouth Cigarettes in a stylish green and white package.

Collectors of these vintage records take such tender care of their treasures nowadays that it is painful to recall how casual one was at the time such discs were bought. We just spun them until they broke. Columbia records were laminated and lasted longer than the brittle Victors and Brunswicks, but all of them were nearly as transitory as the hot cheese kistwich sold at Allen's or the gooey strawberry jigger invented at Saia's. The only sanctuary for records was the back storage bin of a fraternity house console, harboring old echoes like Whiteman's 1925 "Charleston," the California Ramblers' "Sweet Georgia Brown," Abe Lyman's "12th Street Rag," Waring's "Collegiate," Ted Lewis' "Some of These Days" with Sophie Tucker belting out the vocal. There might even be a now rare and valuable jazz treasure like Fletcher Henderson's 1925 "Sugar Foot Stomp," with Louis Armstrong playing three red-hot trumpet choruses that still churn the blood.

In 1928, fans bought the latest Duke Ellington, Johnny Hamp or Jacques Renard, Paul Ash, Rudy Vallee or Jan Garber, or any of dozens of other name bands. The best male vocalist was Gene Austin or Cliff Edwards. Nearly everyone bought Ruth Etting or Paul Whiteman hits from the Broadway musical Whoopee! The top songs from that great show were "Makin' Whoopee" (sung by Eddie Cantor), "My Baby Just Cares for Me," "Love Me or Leave Me" (a Ruth Etting top seller), and "I'm Bringing a Red Red Rose." When Bill Scherman played banjo in the Commons Orchestra his freshman year, the first number they put together was "My Baby Just Cares for Me." They played it, rested, then played it again. For about three weeks. He said: "The rolls flying up at the balcony stirred us to new heights and after a while we got some ad- ditional arrangements."

Jazz was to be heard on radio, especially late in the evening. Temp Nieter '31 remembered that any dorm radio receiver had to be dry-battery powered because the College electrical service was 220-volt direct current. He said: "Appliances like toasters and percolators were proscribed. If found by campus policeman Spud Bray, they were confiscated. My record amplifier was a very early electrical pick-up, which used the sacred 220-volt direct current for plate power and a six-volt storage battery for filaments. Spud never caught on."

Carnival in 1929, featuring a show called Double Trouble by Charles Gaynor '29, was a major event in the realm of song and dance. The month of March that year was enlivened by the first of a new series of Victor "race" records (as they were called). These 150 or so hot dance records by black bands were choice additions to a jazz library. Among the best of the sides were 6 Henry Aliens, 3 Johnny Dodds, 16 Duke Ellingtons, 3 Paul Howards, 12 McKinneys, 14 Jelly-Roll Mortons, 12 marvelous Bennie Motens, 10 King Olivers, 9 Tiny Parhams (one of the hottest of all bands), 5 Victoria Spiveys, 8 Fats Wallers, 3 Clarence Williams, 8 Fess Williams, and a sprinkling of white bands that sounded hot enough to rate inclusion. Three thousand dollars would hardly buy a complete run of this series today.

March in Hanover also brought what later was known as "schlump." It was the duckboards-across-campus season of melting snow. Weather advisories said "mud has rendered the roads in Vermont almost impassable." Jazz was a welcome alternative for the marooned student.

As promised, the Nugget introduced talkies at Dartmouth in August of 1929. It was an RCA system called Photophone. Admission was increased from two bits to 35 cents. The patrons also got a comedy short (mostly with sound) and a newsreel or sports short with screen captions. Many excellent musicals were advertised in TheDartmouth, including Street Girl with Betty Compton, Jack Oakie, and Ned Sparks. Matinees at 2:00 and 3:45. Students' show at 6:45 and townspeople's at 8:30. The wisecracks from the audience at the 6:45 show were often worth the full price of admission.

WHO were some other Dartmouth jazz musicians of that period? Duke Sarles '30 held down the trumpet chair in the official jazz band for the 1929 Musical Clubs tour. Heinie Stewart (or Johnny Sanders) were Class of '30 trombonists. Dick Olmsted '32 followed Stewart for two years. Chuck Peacock '30 was a short-term but well-remembered banjoist. The Class of'31 contributed a one-of-a-kind, Roger Burrill, whose adventures in music were original and memorable:

Joe Linz '31 and I began writing songs together when we were sophomores [Burrill wrote recently]. It was his idea. We spent a good deal of time together over the beat-up grand piano that used to be in the lobby of Commons - and evening hours in "Z" Webster creating — and composing. Finally, we developed enough of a book and a sufficient number of songs so that the Music Department (Professor Maurice Longhurst, that is) decided it was possible to produce another Carnival Show. So along came Exit Smiling, which opened February 7, 1930.

It was a potpourri of efforts by Joe and me, Paul Freeman and Frank Marks, writers Tom Donovan '30 and Milt Lieberthal '32. Plus several songs by graduate Charles Gaynor '29. The best song from Linz and Burrill was "Deep Sea Lowdown." Joe Linz' father had interests in a Dallas hotel which had engaged Bernie Cummins and his orchestra [a big band that had scored at least one hit on Victor: "Little By Little"]. Bernie thought he could place the song if we cut him in for one-third. It was published, arranged, and recorded. I was convinced I had a brilliant career ahead of me in song writing. Victor released it on Victor 24053, on the "B" side of a Ted Weems "Play That Hot Guitar." I sat and waited for my first royalty check. It finally came: $6.59. At this point I realized that I was going to have to go out and find some kind of a job.

Some three months before Exit Smiling came the Depression, in October 1929. Although The Dartmouth for October 25th carried the banner headline "GREEN AND CRIMSON AWAIT ANNUAL GAME AS STUDENT BODY DESCENDS UPON CAMBRIDGE" — and a second lead story noted "Possibilities Arise of Gridiron Contest with Notre Dame" — the third front-page news item was that "Stocks Take Downward Plunge During Frantic Day of Selling."

The rest of 1929-30 at Dartmouth was a musical hodgepodge. Yes, it was a big movie year. The Broadway Melody was full of hit songs, including "You Were Meant For Me." Big band programs were crowding the evening hours on radio. Record buyers had a choice of "When You're Smiling" by gravel-voiced Louis Armstrong, "Am I Blue" by Ethel Waters, or "Moanin' Low," which Libby Holman sang in a new style as the first great torch song. Nick Lucas rode lightly through "Tiptoe Through the Tulips" (faithfully copied a generation or two later by Tiny Tim). Fats Waller talked to his piano with "Ain't Misbehavin'." Rudy Vallee hypnotized the girls with "I'm Just a Vagabond Lover." Hoagy Carmichael's immortal "Stardust" got its third and best recording (even without a vocal) by Irving Mills and his Hotsy Totsy Gang, with Miff Mole, Jimmy Dorsey, Pee Wee Russell, and Hoagy himself on piano.

The Barbary Coast was much in evidence at party time. They starred at the Statler during the Harvard-Dartmouth game weekend, although until the last minute the band was touted as a prime attraction at the rival ball at the Copley Plaza. At fall House Parties the Coast held forth at Tri Kap. They were then signed fat the first Green Key prom in March. Over the Christmas holiday they were picked from a large group of Eastern college orchestra candidates for the nine-day West Indies cruise of the Cunard liner S.S. Carmania. The band included Johnny Hahn '30, leader, Jeff Jeffrey, George Sarles, Paul Freeman, Frank Hodson, Frank Marks, and Gene Hammett '33, a talented freshman sax player who' later led the band. For the Carnival Ball, the Barbary Coast held forth in the Trophy Room at the gymnasium while Paul Specht and his orchestra played in the cavernous gym upstairs. The Coast's earlier model had been Paul Whiteman. Later, it was Casa Loma. At this time, it was just a well-knit group having fun with all the current hit songs.

In the summer of 1930, a year before Roger Burrill "went out and found a job," he was in solitary business in Hanover:

I worked at the Campus Cafe for my meals, and lived free at the Theta Chi house. I spent a great deal of time evenings at the piano in front of a huge Victor Orthophonic radio, learning new tunes from the dance orchestras playing in hotels and ballrooms all over the country. After the news at 11:00 p.m., the listener could tune New York stations, then Cincinnati, then Chicago, and even Denver to hear the latest popular songs.

As I listened, I would copy down the melody lines, note the harmony, and then, next day, write out the individual instrument parts in music notebooks — one for each instrument. I wrote trio arrangements for the saxophones, then the melody for the trumpet with "held notes" in the background for the sax section. No fancy rhythm or special phrasing. A clarinet or piano could play straight melody, too.

By September, I had about 200 of these new popular songs in the "book" and was ready for action. I assembled a group: Bob House '32, drums; Bob McHose '32, trumpet; Hubie Glass '31, alto sax; and Ben Hardman '31, tenor sax. Ben also played a beautiful bass clarinet.

We wangled a house party job for five pieces at Norwich University, and a couple of dances in Hanover. We recruited Bill Truex '30 on alto sax, Ernie Lanoue '32 on tenor sax, and Wayne Van Leer '30 on rhythm guitar, a new development. I had a large banner made. It said "THE GREEN VAGABONDS." We also had small megaphones and sang together. Oh, we were crowd pleasers, all right. We had bookings nearly every weekend. We did funny little acts. The Barbary Coast, of course, took all the important jobs on campus, but we found more than enough business coming our way.

In June of 1931, we had a contract playing for the tenth reunion of.the Class of 1921. We got rolling on "China Boy," a red hot number. One of the '21 girls began to dance solo, and take off her clothes. After a while one of the committee asked me to stop the music. The young lady went back to her seat and put her clothes back on. Our music must have been powerful stuff.

The most popular songs of 1930 and 1931 included "Betty Co-Ed" on the new 15-cent "Hit of the Week" paper records; "Body and Soul" by Leo Reisman on Victor; "Memories of You," composed by Eubie Blake and sung with deep feeling by Louis Armstrong; "Three Little Words" by Duke Ellington and Bing's Rhythm Boys; "Love For Sale," a scorcher-torcher by Ruth Etting; "If I Could Be With You One Hour Tonight" by McKinney's Cotton Pickers, who played at the Statler Hotel dance after the Harvard-Dartmouth game of 1930; "Sweet and Lovely," which Gus Arnheim used as a theme song; Cab Calloway's hi-de-ho treatment of "Minnie the Moocher"; and So many more.

BY the start of the college year in September 1931, the Depression was beginning to bite deep. In musician slang, things were down to "twos and fews." The lucky ones who were able to stay in college tried every which way to make a buck. This certainly was true of the college dance bands. Gene Hammett '33, tenor sax, found gigs for the Barbary Coast. His mainstays were Hank Rigby '34 and Jack Mahan '34 on trumpet, Bill French '34 on trombone, Frank Hardy '33 and Bill Gay '34 with Hammett in the reed section, Chuck Stege '33 on brass bass, Frank Marks '32 as piano man for his fourth year, and Stan Abercrombie '34 on drums and xylophone.

Gene Hammett was remembered by Bill Scherman as able to play just about any instrument. He was a prominent band leader in the New England area for many years. Abercrombie recently reminisced that "Now and then at rehearsals Gene passed out parts for new orchestrations he had received from music publishers. We'd sight-read these new pieces and then vote on whether to add them to our repertoire. When we voted to discard any number, Hammett would count one-two as though starting us off. But what we did was tear the music in half simultaneously." Hammett was leader of the band in '31-'32 and '32-'33.

Hank Rigby played with the Coast for four years. Scherman called him "a most imaginative trumpet player — by far the best improviser in school at the time." Abercrombie wrote: "Hammett and Rigby were hotshots at listening to records — over and over — and getting down the separate parts for first and second trumpets, the various saxes, etc. One number we played many times was 'Casa Loma Stomp,' taken down on manuscript paper directly from Glen Gray's record. We also played 'Smoke Rings' - taken directly from the record. Our theme song was 'On the Alamo,' and our final number was the customary 'Good Night, Ladies.' "

Every Barbary Coast alumnus seems to have his own personal recollection about the four-year piano genius Franklyn Marks '32. Hank Rigby commented: "Marks was, I believe, a straight four-point man [all A's], and habitually read a book while playing rhythm." Abercrombie recalled: "We traveled a lot in one of Hanover's seven-passenger Cadillac taxis. Marks would assign a given note to each man — which we'd then sing together on his signal. It was always an interesting chord."

"Stan Abercrombie was the Coast's drummer," wrote Scherman. "He also soloed on xylophone — using all four mallets." As a freshman, Abercrombie earned a rave review in The Dartmouth for his solo on "Hot Foot" in a College band concert. Rigby spoke of a summer engagement in the Catskills when their trombone player was Littleton Holmes Fitch from Amherst, "which gave us the delightful opportunity of announcing two members of the band as Abercrombie and Fitch."

NINETEEN THIRTY-TWO forced more economies at Dartmouth. Six freshman sports were dropped. The Coast was now minus Frank Hardy '33, gaining Frank Weston '36; Stege and his bass horn graduated, but the band brought in Bob Ford on bass fiddle and named Jack Gilbert '34 on piano. Top tunes of the year were "42nd Street," "Night and Day," "April in Paris," and, biggest of all, "Smoke Rings," the theme song of the idolized Glen Gray and his Casa Loma Orchestra.

During the Green Key prom (or Carnival?) of 1932, the Coast broadcast on Lucky Strike's big weekly program with Walter Winchell. This 60-minute show on a national network featured leading dance bands — a couple from the East — then a "magic carpet" switch to the West Coast. For the Barbary Coast, Jack Mahan's classic-style trumpet took a solo. Most of Dartmouth headed to the nearest available radio for this delicious ego-trip.

The Casa Loma band played for the 1934 Green Key prom while the Coast played during intermission, in the Trophy Room of the gym. Stan Abercrombie wrote: "Someone persuaded Glen and his men to come listen to the Coast, and what did we give 'em? 'Casa Loma Stomp.' They seemed to enjoy it, and were surprised that we had manuscript for all the parts." At the prom held the following year, the Dorsey Brothers and Fletcher Henderson alternated in the upper part of the gym, and the Barbary Coast again performed in the Trophy Room.

The Green Serenaders were still going strong in these years. Bill Scherman was their banjo player at first, then learned bass fiddle to qualify for an open spot in the band. Paul Weston was the piano player, arranger, and leader. He was Frank Weston's older brother. Bob Saywell '33, sax, teamed on reeds with Frank Weston and Lowell Haas '35, who later moved to the Barbary Coast and was their leader. Ralph Specht '35 and Gil Portmore '36 were the trumpets. Wilson Ferguson '36 played drums. Later, the band had Al Clark '35, Dallas Leitch '36, Don Andrus '36, and Jim Conkling '36. Fred Raymond '35 also played piano with this band.

WHAT had started out in the early 1920s as a scattering of hardy pioneers in student dance bands was now becoming overrun with talent in a rather profitable year-round business operation. The 1935 Aegis listed Barbary Coast personnel as two trumpets, two trombones, three saxes, piano, bass, and drums, and said they were engaged practically every weekend at women's colleges and suburban clubs. They traveled 7,000 miles - yet the scholastic average of the members was at the Phi Beta Kappa level. Their music library consisted of more than 200 numbers, half of which had been arranged by members of the orchestra. The Aegis report concluded: "The Coast is to spend the summer aboard the S.S. Volendam on its annual cruise to the Mediterranean and North Cape." A visit to 12 countries, 26 cities. Free travel of more than 13,000 miles. (No mention was necessary of fringe benefits like parties and female companionship.)

The Barbary Coast recorded on the Columbia Personal label in 1924 and 1927. These records did not get national distribution, but sold well to the students in Hanover. Now, in 1935, the Barbary Coast was invited by Decca to record for general release. Bill Mann '35 recalled: "We made that recording right on the eve of departure for an eight-week Holland-America cruise to Europe. At the last minute, we were called and given our choice of two out of three tunes. I stayed up practically all night for two nights in order to arrange the tunes we picked and be in time for a rehearsal the day before we recorded. My sister was the vocalist. I found I had voiced one number far above her range. Anyway, we had a lot of frantic trasnposing to do just prior to recording." Malcolm Rowell, Jim Conkling, and Hickey Hecox from Colgate played trumpet. George Zeluff had the trombone duties normally handled by Hunt Sutherland. The saxes were Lowell Haas, leader, Frank Weston, and Don Andrus. Bill Mann played piano, Bill Bury was on bass, and Sev Vass was on drums. "The tunes we had selected," wrote Haas, "were 'Star Gazing' and 'Sweet and Low.' They were in the Casa Loma style. Sis Mann did the vocals. She later married our drummer Sev Vass." Not until they returned from the cruise did they find out that Decca had released the record (Decca 501). "We could not have cared less whether it was a million-seller," said Bill Mann. "All we were intrigued with was the idea that we actually recorded for a major record company." Copies of this disc show up every now and then on auction lists.

Nothing much else of importance happened in music that summer — except, possibly, the night in August, at the Palomar Ballroom in Los Angeles, when the fledgling Benny Goodman Orchestra captured the crowd, and the era of the Big Bands was born.

The Green Serenaders aboard the Puerto Rico Lines' Coama, Easter vacation, 1934(from left): Bill Scherman, Jim Conkling, Gil Portmore, Dallas Leitch, Wilson Ferguson, Fred Raymond, Al Clark, Don Andrus, and Ralph Specht. A "Casa Loma"pose.

The 1933-34 Barbary Coast in formal pose (from left): Hunt Sutherland, Bob Ford, MacRowell, Hank Rigby, Stan Abercrombie, Lowell Haas, Jack Gilbert, Frank Weston, Bill Gay.

For last November's issue, Dick Holbrook'31 wrote "Jazz Comes to College," aboutthe first dozen years, 1915 to 1927, of thenew music at Dartmouth. He began collectingjazz records at about the time this second chapter begins.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureE – i – e – i – o

June 1979 By Marshall Ledger -

Feature

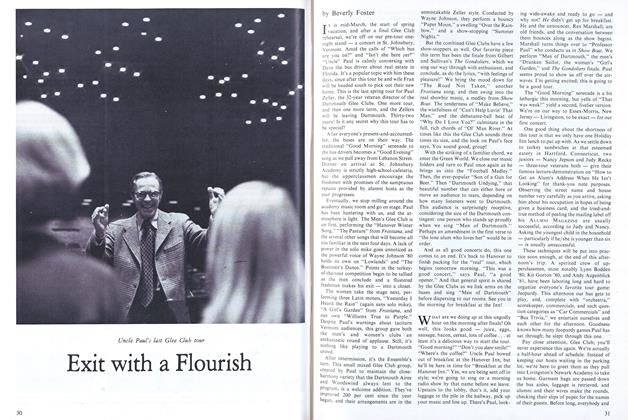

FeatureExit with a Flourish

June 1979 By Beverly Foster -

Feature

FeatureEncouraging growth, affirming the educational process

June 1979 By Robert Kilmarx -

Article

ArticleCommencement

June 1979 By James L. Farley -

Article

Article'Radical' with a Cause

June 1979 By Tim Taylor -

Article

ArticleThe Bottom Line

June 1979

Features

-

Feature

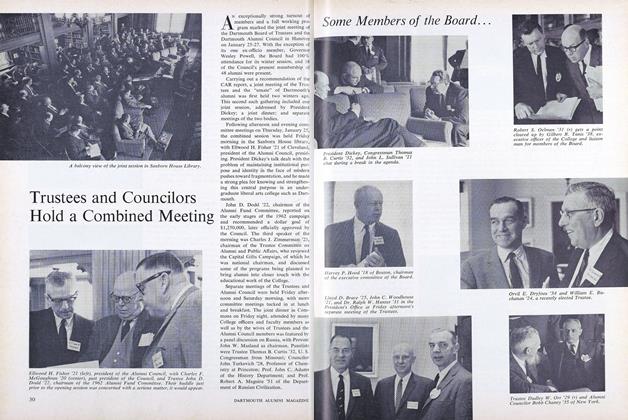

FeatureSome Members of the Board...

March 1962 -

Feature

FeatureMELANIE BENSON

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Feature

FeatureTHE CLASSICS

March 1962 By NORMAN A. DOENGES -

Feature

Feature"The Highest-Ranking Woman in American History"

MAY 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureChairman's Report

December 1957 By William G. Morton '28 -

Feature

FeatureThe Rise and Fall of Humanity

MARCH 1970 By WILLIAM W. BALLARD '28