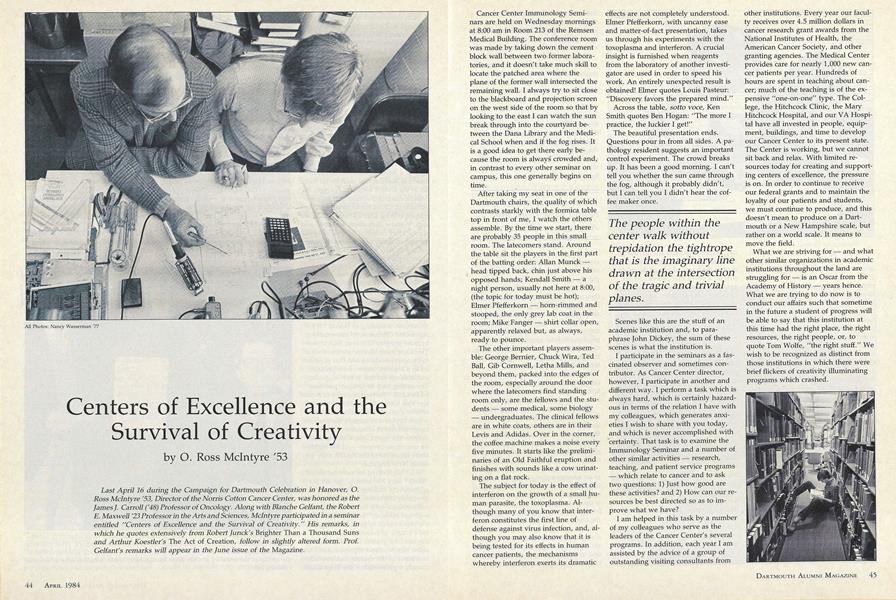

Last April 16 during the Campaign for Dartmouth Celebration in Hanover, O. Ross Mclntyre '53, Director of the Norris Cotton Cancer Center, was honored as the James J. Carroll ('48) Professor of Oncology. Along with Blanche Gelfant, the Robert E. Maxwell '23 Professor in the Arts and Sciences, Mclntyre participated in a seminar entitled "Centers of Excellence and the Survival of Creativity." His remarks, in which he quotes extensively from Robert Junck's Brighter Than a Thousand Suns and Arthur Koestler's The Act of Creation, follow in slightly altered form. Prof. Gelfant's remarks will appear in the June issue of the Magazine.

Cancer Center Immunology Seminars are held on Wednesday mornings at 8:00 am in Room 213 of the Remsen Medical Building. The conference room was made by taking down the cement block wall between two former laboratories, and it doesn't take much skill to locate the patched area where the plane of the former wall intersected the remaining wall. I always try to sit close to the blackboard and projection screen on the west side of the room so that by looking to the east I can watch the sun break through into the courtyard between the Dana Library and the Medical School when and if the fog rises. It is a good idea to get there early because the room is always crowded and, in contrast to every other seminar on campus, this one generally begins on time.

After taking my seat in one of the Dartmouth chairs, the quality of which contrasts starkly with the formica table top in front of me, I watch the others assemble. By the time we start, there are probably 35 people in this small room. The latecomers stand. Around the table sit the players in the first part of the batting order: Allan Munck head tipped back, chin just above his opposed hands; Kendall Smith a night person, usually not here at 8:00, (the topic for today must be hot); Elmer Pfefferkorn horn-rimmed and stooped, the only grey lab coat in the room; Mike Fanger shirt collar open, apparently relaxed but, as always, ready to pounce.

The other important players assemble: George Bernier, Chuck Wira, Ted Ball, Gib Cornwell, Letha Mills, and beyond them, packed into the edges of the room, especially around the door where the latecomers find standing room only, are the fellows and the students some medical, some biology undergraduates. The clinical fellows are in white coats, others are in their Levis and Adidas. Over in the corner, the coffee machine makes a noise every five minutes. It starts like the preliminaries of an Old Faithful eruption and finishes with sounds like a cow urinating on a flat rock.

The subject for today is the effect of interferon on the growth of a small human parasite, the toxoplasma. Al though many of you know that interferon constitutes the first line of defense against virus infection, and, al though you may also know that it is being tested for its effects in human cancer patients, the mechanisms whereby interferon exerts its dramatic effects are not completely understood. Elmer Pfefferkorn, with uncanny ease and matter-of-fact presentation, takes us through his experiments with the toxoplasma and interferon. A crucial insight is furnished when reagents from the laboratory of another investigator are used in order to speed his work. An entirely unexpected result is obtained! Elmer quotes Louis Pasteur: "Discovery favors the prepared mind."

Across the table, sotto voce, Ken Smith quotes Ben Hogan: "The more I practice, the luckier I get!"

The beautiful presentation ends. Questions pour in from all sides. A pathology resident suggests an important control experiment. The crowd breaks up. It has been a good morning. I can't tell you whether the sun came through the fog, although it probably didn't, but I can tell you I didn't hear the coffee maker once.

Scenes like this are the stuff of an academic institution and, to paraphrase John Dickey, the sum of these scenes is what the institution is.

I participate in the seminars as a fasinated observer and sometimes contributor. As Cancer Center director, however, I participate in another and different way. I perform a task which is always hard, which is certainly hazardous in terms of the relation I have with my colleagues, which generates anxieties I wish to share with you today, and which is never accomplished with certainty. That task is to examine the Immunology Seminar and a number of other similar activities research, teaching, and patient service programs which relate to cancer and to ask two questions: 1) Just how good are these activities? and 2) How can our resources be best directed so as to improve what we have?

I am helped in this task by a number of my colleagues who serve as the leaders of the Cancer Center's several programs. In addition, each year I am assisted by the advice of a group of outstanding visiting consultants from other institutions. Every year our faculty receives over 4.5 million dollars in cancer research grant awards from the National Institutes of Health, the American Cancer Society, and other granting agencies. The Medical Center provides care for nearly 1,000 new cancer patients per year. Hundreds of hours are spent in teaching about cancer; much of the teaching is of the expensive "one-on-one" type. The College, the Hitchcock Clinic, the Mary Hitchcock Hospital, and our VA Hospital have all invested in people, equipment, buildings, and time to develop our Cancer Center to its present state. The Center is working, but we cannot sit back and relax. With limited resources today for creating and supporting centers of excellence, the pressure is on. In order to continue to receive our federal grants and to maintain the loyalty of our patients and students, we must continue to produce, and this doesn't mean to produce on a Dartmouth or a New Hampshire scale, but rather on a world scale. It means to move the field.

What we are striving for and what other similar organizations in academic institutions throughout the land are struggling for is an Oscar from the Academy of History years hence. What we are trying to do now is to conduct our affairs such that sometime in the future a student of progress will be able to say that this institution at this time had the right place, the right resources, the right people, or, to quote Tom Wolfe, "the right stuff." We wish to be recognized as distinct from those institutions in which there were brief flickers of creativity illuminating programs which crashed.

I am going to describe a scene from one of the all-time great centers of excellence. Between the years 1923 and 1932, young investigators in nuclear physics congregated in Gottingen, Germany. From this small town came all kinds of revelations. As one examines the history of this phenomenon, it is clear that much of what happened can be attributed to the leadership provided by Professor Felix Klein. "Klein sat in the chair previously occupied by the mathematician, Carl Friederich Gauss, and enhanced its reputation, not only by his accomplishments as a thinker, but by his work as a bold, tireless, and inspired organizer. After a journey to America in 1893, Klein undertook the abolition of the distinction, which at that time was strictly maintained in Europe, between pure science and its various applications. Klein initiated the foundation or further extension of many astronomical, physical, technical, and mechanical institutes in Gottingen. There gradually grew up around them in consequence a whole private industry for the production of scientific measuring apparatus and optical precision instruments."

Outstanding mathematicians who were utterly opposed to Klein intellectually, were invited to Gottingen, and bright students throughout the world flocked to the university, where they helped to create the climate for scientific progress. It is said that every Thursday at three o'clock in the afternoon, selected members of the faculty gathered at the home of one of the professors on a porch that overlooked his garden. There, on a big blackboard, formulae were scribbled and argued over. Then the discussion would continue while participants climbed through the woods and over the open fields in all kinds of weather up to a hotel on the heights. There, over coffee, the arguments would continue, until, and I quote Robert Junck, "Reaching the most rarefied atmosphere of the limits of human understanding, loud laughter would intervene, giving comfort and relaxation to minds that had reached the seemingly unconquerable frontiers." (Think of this scene the next time you are stuck bumper-to-bumper on the freeway!)

To this stimulating town, a young Austrian, Fritz Houtermans, and a young Englishman, Geoffrey Atkinson, came in the mid-19205. "One hot summer day in 1927, during a walking tour, the two passed the time of day by raising partly as a joke the old, unsolved problem of the true source of the inexhaustible energy supplied by the sun that was beating down upon their heads. There could be no question that this was not an ordinary process of combustion, otherwise the substance of the sun must long since have been consumed in the fierce heat generated for so many millions of years. But, ever since Einstein's formula of the interchangability of matter and energy, the suspicion had been growing that in all probability a process of atomic transmutation fueled the sun.

"Atkinson had participated in Rutherford's experiments at Cambridge. He suggested to his companion that what had been accomplished at the Cavendish laboratory must also be possible in the sun.

"This was the origin of the labors of Atkinson and Houtermans on their theory of thermo-nuclear reactions in the sun. They challenged the concept that the energy of the sun was due to the demolition of atoms and hypothesized that it was the fusion of light weight atoms which was responsible for solar energy."

Houtermans later reported, "That evening after we had finished our essay, I went for a walk with a pretty girl. As soon as it grew dark, the stars came out, one after the other, in all their splendor. 'Don't they sparkle beautifully?' cried my companion, but I simply stuck out my chest and said, proudly, 'I have known since yesterday why it is they sparkle.' She didn't seem in the least moved by this statement; perhaps she didn't believe it. At that moment, probably, she felt no interest whatever in the matter."

My chief concern as the director of a cancer center is that I might, as Houtermans' girlfriend, miss the significance behind the twinkle of a star.

What clues can one use to identify those centers with developing excellence? What indications does one have that a center is fading? How does one tell the difference between momentary glitter and the long, hot burn of a true star?

I contend that we are really no closer to an administrative or organizational formula for creativity in the scientific centers than we are to a general formula for creativity in the arts. However, I believe there are helpful clues given by the history of previously successful centers of excellence. These include the ability of the center to support, tolerate, and encourage diversity of thought and to debate concepts which are never less than controversial.

Another characteristic of creative centers is that the people within the center walk without trepidation the tightrope so beautifully described by Arthur Koestler. This tightrope is the imaginary line drawn at the intersection of what he refers to as the "tragic and trivial planes." To walk the rope is "to embark on the Night Journey."

"This journey appears in countless disguises throughout the history of art and science. Under the effect of some overwhelming experience, the hero is made to realize the shallowness of his life, the futility and frivolity of the daily pursuits of man and the trivial routines of existence. The realization may come to him as a sudden shock caused by some catastrophic event, as the cumulative effect of a slow inner development, or as a .trigger action of some apparently banal experience suddenly given unexpected significance.

"The hero then suffers a crisis which involves the very foundations of his being; he embarks on the Night Journey, is suddenly transferred to the tragic plane from which he emerges purified, enriched by new insight, regenerated on a higher level of integration.

"Among the many variations of the Night Journey in myth and folklore is the story of Jonah and the whale. In no ancient civilization was the tension between the tragic and trivial planes more intensely felt than by the Hebrews. The first was represented by the endless succession of invasions and catastrophies, the exacting presence of Jehovah and of his apocalyptic prophets. The second, by the rare periods of relatively normal life which the overstrung spiritual leaders of the tribe condemned as abject.

"Jonah had committed no crime which would warrant his dreadful punishment: he is described as a quite ordinary and decent fellow with just a streak of normal vanity. Now this very ordinary person receives at the beginning of the story God's sudden order to go to Nineveh, that great city, and cry against it. This is a tall order, for Jonah is no professional priest or prophet. He prefers to go on leading his happy and trivial life, so instead of responding to the call from the tragic plane, he buys a passage on a ship to Tarshish: and he has such a clean conscience about it, that while the storm rages and the sailors cry, 'Every man unto his God!' and throw the cargo into the sea, Jonah is fast asleep.

"His sin lies in his normality his complacency, in his thick-skinned triviality and refusal to face the storm and God. In turning his back on the tragic essence of life, he is led into his crisis to the Night Journey in the belly of the whale, in 'the belly of hell.'

"Jonah's only crime was to cling to the trivial plane and to cultivate his little garden, trying to ignore the uncomfortable, unjust, terrible voice from the other plane. Melville understood this when in the great sermon in MobyDick he made his preacher sum up the lesson of Jonah and the whale in this unorthodox moral:

Woe to him who seeks to pour oil upon the waters when God has brewed them into a gale! Woe to him who seeks to please rather than appall! Woe to him whose good name is more to him than goodness! Woe to him who, in this world, courts not dishonor!

"The ordinary person in our urban civilization moves virtually all his life on the trivial plane: only a few dramatic occasions during the storms of puberty, when he is in love or in the presence of severe illness or death does he suddenly fall through the manhole and is transferred to the tragic plane. But the interlacing of the trivial and of the tragic planes is found in all great works of art, and at the origin of all great discoveries of science. The artist and the scientist are condemned or privileged to walk on the line of intersection as on a tightrope for much of their lives. At his best moments, man lives as a true amphibian in a divided and anguished world."

Individuals whose ambitions take them to the intersection of the planes, institutions that anchor the tightrope, practice (or luck), and tolerance of performances which may, at first, appall, comprise the stuff of excellence. The stuff without which creativity hisses

and goes out. Those of us who are charged with the nurture of excellence appreciate the support and encouragement we have been given. If

The people within thecenter walk withouttrepidation the tightropethat is the imaginary linedrawn at the intersectionof the tragic and trivialplanes.

What we are striving foris an Oscar from theAcademy of History.

How does one tell thedifference between mo-mentary glitter and thelong hot burn of a truestar?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryConsortium

April 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureHanover Sabbatical

April 1984 By Robert Conn '61 -

Feature

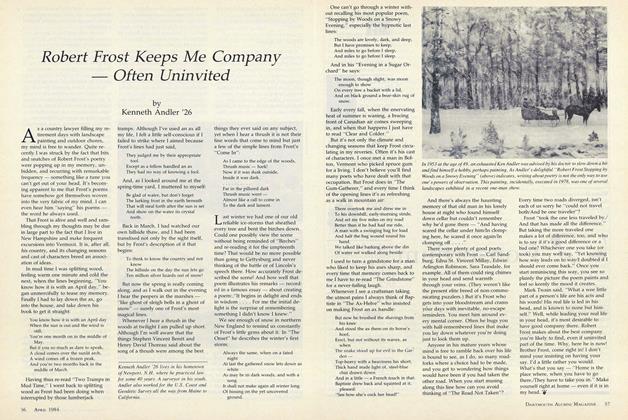

FeatureRobert Frost Keeps Me Company Often Uninvited

April 1984 By Kenneth Andler '26 -

Article

ArticleIt's Just Like Talking to People

April 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

April 1984 By William G. Long -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

April 1984 By Harry R. Zlokower

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

JULY 1965 -

Feature

FeatureThayer's Two Track Program

MARCH 1967 -

Feature

FeatureThird Century Fund Launches General Campaign Among Alumni

OCTOBER 1969 -

Cover Story

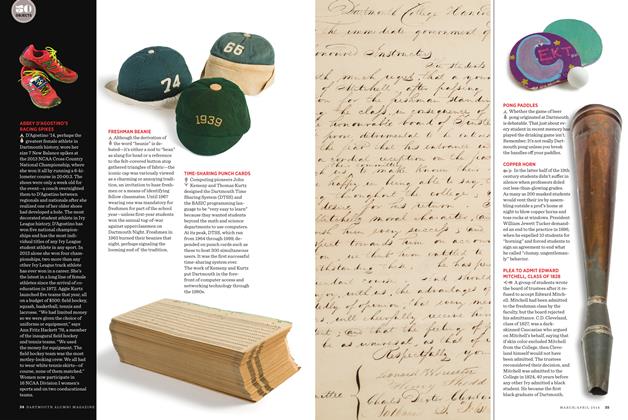

Cover StoryTIME-SHARING PUNCH CARDS

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

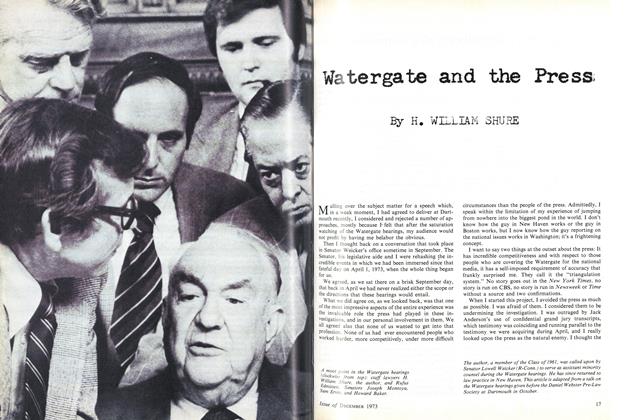

FeatureWatergate and the Press

December 1973 By H. WILLIAM SHURE -

Feature

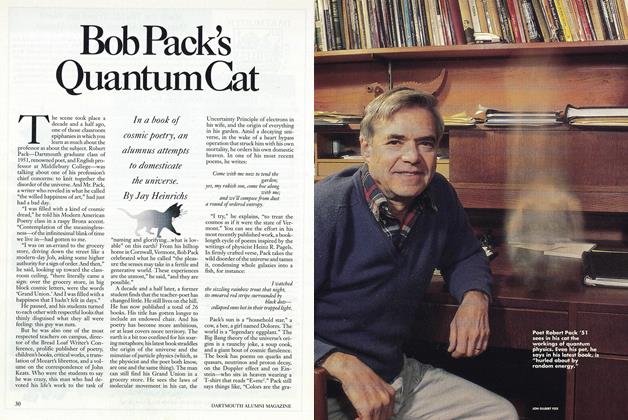

FeatureBob Pack's Quantum Cat

December 1989 By Jay Heinrichs