Perhaps the League of Women Voters had in mind the imposing reputation of Dartmouth's Forensic Union when it decided not to invite Libertarian Party candidate Ed Clark '52 to its presidential debate in Baltimore this September. Anderson, Reagan, and, more importantly, collegiate orators nationwide have just cause to fear our debaters: Over the last 30 years, Dartmouth has advanced to the national debate tournament 26 times, winning the national title three of those years; more recently, Dartmouth has ranked among the top 16 teams in the country for three years running.

The architect of all this success, Herbert James, the Israel Evans Professor of Oratory and Belles Lettres, has coached the Forensic Union's activities for 30 years and can truthfully be labeled an expert on polemics. Looking forward to the second presidential debate, we asked him to criticize the first as if it were a college forensic competition. His appraisal: "On a scale of one to ten, this debate would be a two, and the championship round of the national intercollegiate debating tournament would be a ten."

James professorially ticked off the qualities that Republican Ronald Reagan and independent John Anderson should have been striving for: clarity of speech, responsiveness to the question, specific and ample supporting evidence, demonstration of the efficacy of the advocated means toward the desired goal, and detailed refutation of the opponent's argument. A debate, James noted, is "more concerned with the truth of an idea than with its impact on the listener, with what is more right than wrong." It should, in short, persuade rather than appeal.

The television debate, however, was more than a collegiate exercise it was a political escapade, and therefore did not conform to the objectivity and reason that predominate in a college debate. Instead, the aim was to elicit responses by such emotional factors as the candidate's image and the appeals he makes to the people's desires, opinions, and hopes. Reagan's conclusion, for example, wasn't a summation of his positions at all, James contended. It was an emotional appeal, paraphrased James, "to our heritage, to our mountains, to our deserts, to the American people. But that has a certain appeal to the American voter."

In the final count, James does not think that the debate changed many minds. Reagan and Anderson supporters probably remained Reagan and Anderson supporters, and as for the voters in the middle, they remained in the middle confused. Despite all of these failings, however, the debate did represent an improvement on no debate, James said. "The candidates do attempt to come to grips with their differences and their similarities. We get a slightly better picture of where they stand, given specific questions and specific responses. They probably should improve the format, though; the candidates should engage in battle instead of passing in the night."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHAIR

November 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureNow Let Him Praise Emmets

November 1980 By Robert Sullivan -

Feature

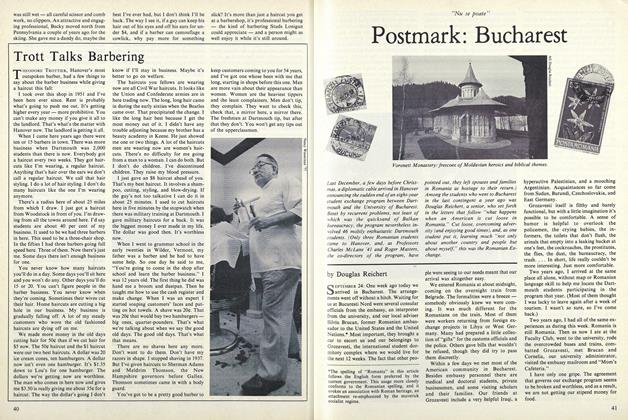

FeaturePostmark: Bucharest

November 1980 By Douglas Reichert -

Article

ArticleTrusteeship and the Alumni

November 1980 -

Article

ArticleUnofficial Arbiter

November 1980 By Patricia Berry '81 -

Article

ArticleWanted: Road-trip Messerly

November 1980 By Parker B. Smith '66

Article

-

Article

Article"THE BIGGEST GREEN TEAM"

January 1920 -

Article

Article"ATHLETICS AT DARTMOUTH" AN ATTRACTIVE VOLUME

June, 1923 -

Article

ArticleHamilton Prexy

October 1938 -

Article

ArticleGeography Address

March 1944 -

Article

ArticleTHAYER SCHOOL REPORT ALUMNI FUND, 1942

January 1943 By F.H. Munkelt '08 -

Article

ArticleThe Call Heard Round the World

OCT. 1977 By S.G.