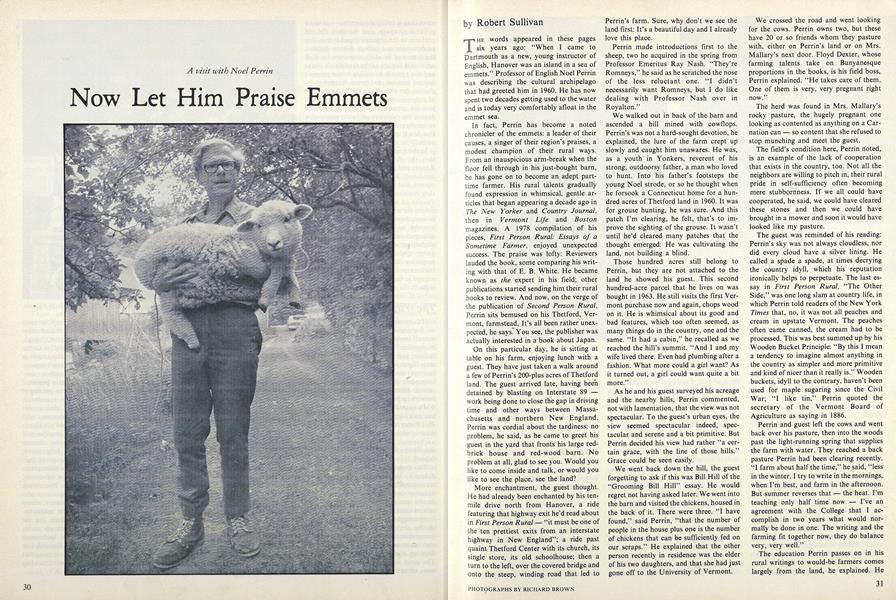

A visit with Noel Perrin

THE words appeared in these pages six years ago: "When I came to Dartmouth as a new, young instructor of English, Hanover was an island in a sea of emmets." Professor of English Noel Perrin was describing the cultural archipelago that had greeted him in 1960. He has now spent two decades getting used to the water and is today very comfortably afloat in the emmet sea.

In fact, Perrin has become a noted chronicler of the emmets: a leader of their causes, a singer of their region's praises, a modest champion of their rural ways. From an inauspicious arm-break when the floor fell through in his just-bought barn, he has gone on to become an adept parttime farmer. His rural talents gradually found expression in whimsical, gentle articles that began appearing a decade ago in The New Yorker and Country Journal, then in Vermont Life and Boston magazines. A 1978 compilation of his pieces, First Person Rural: Essays of aSometime Farmer, enjoyed unexpected success. The praise was lofty: Reviewers lauded the book, some comparing his writing with that of E. B. White. He became known as the expert in his field; other publications started sending him their rural books to review. And now, on the verge of the publication of Second Person Rural, Perrin sits bemused on his Thetford, Vermont, farmstead. It's all been rather unexpected, he says. You see, the publisher was actually interested in a book about Japan.

On this particular day, he is sitting at table on his farm, enjoying lunch with a guest. They have just taken a walk around a few of Perrin's 200-plus acres of Thetford land. The guest arrived late, having been detained by blasting on Interstate 89 work being done to close the gap in driving time and other ways between Massachusetts and northern New England. Perrin was cordial about the tardiness; no problem, he said, as he came to greet his guest in the yard that fronts his large redbrick house and red-wood barn. No problem at all, glad to see you. Would you like to come inside and talk, or would you like to see the place, see the land?

More enchantment, the guest thought. He had already been enchanted by his tenmile drive north from Hanover, a ride featuring that highway exit he'd read about in First Person Rural "it must be one of the ten prettiest exits from an interstate highway in New England"; a ride past quaint Thetford Center with its church, its single store, its old schoolhouse; then a turn to the left, over the covered bridge and onto the steep, winding road that led to Perrin's farm. Sure, why don't we see the land first: It's a beautiful day and I already love this place.

Perrin made introductions first to the sheep, two he acquired in the spring from Professor Emeritus Ray Nash. "They're Romneys," he said as he scratched the nose of the less reluctant one."I didn't necessarily want Romneys, but I do like dealing with Professor Nash over in Royalton."

We walked out in back of the barn and ascended a hill mined with cowflops. Perrin's was not a hard-sought devotion, he explained, the lure of the farm crept up slowly and caught him unawares. He was, as a youth in Yonkers, reverent of his strong, outdoorsy father, a man who loved to hunt. Into his father's footsteps the young Noel strode, or so he thought when he forsook a Connecticut home for a hundred acres of Thetford land in 1960. It was for grouse hunting, he was sure. And this patch I'm clearing, he felt, that's to improve the sighting of the grouse. It wasn't until he'd cleared many patches that the thought emerged: He was cultivating the land, not building a blind.

Those hundred acres still belong to Perrin, but they are not attached to the land he showed his guest. This second hundred-acre parcel that he lives on was bought in 1963. He still visits the first Vermont purchase now and again, chops wood on it. He is whimsical about its good and bad features, which too often seemed, as many things do in the country, one and the same. "It had a cabin," he recalled as we reached the hill's summit. "And I and my wife lived there. Even had plumbing after a fashion. What more could a girl want? As it turned out, a girl could want quite a bit more."

As he and his guest surveyed his acreage and the nearby hills, Perrin commented, not with lamentation, that the view was not spectacular. To the guest's urban eyes, the view seemed spectacular indeed, spectacular and serene and a bit primitive. But Perrin decided his view had rather "a certain grace, with the line of those hills." Grace could be seen easily.

We went back down the hill, the guest forgetting to ask if this was Bill Hill of the "Grooming Bill Hill" essay. He would regret not having asked later. We went into the barn and visited the chickens, housed in the back of it. There were three. "I have found," said Perrin, "that the number of people in the house plus one is the number of chickens that can be sufficiently fed on our scraps." He explained that the other person recently in residence was the elder of his two daughters, and that she had just gone off to the University of Vermont.

We crossed the road and went looking for the cows. Perrin owns two, but these have 20 or so friends whom they pasture with, either on Perrin's land or on Mrs. Mallary's next door. Floyd Dexter, whose farming talents take on Bunyanesque proportions in the books, is his field boss, Perrin explained. "He takes care of them. One of them is very, very pregnant right now."

The herd was found in Mrs. Mallary's rocky pasture, the hugely pregnant one looking as contented as anything on a Carnation can so content that she refused to stop munching and meet the guest.

The field's condition here, Perrin noted, is an example of the lack of cooperation that exists in the country, too. Not all the neighbors are willing to pitch in, their rural pride in self-sufficiency often becoming mere stubbornness. If we all could have cooperated, he said, we could have cleared these stones and then we could have brought in a mower and soon it would have looked like my pasture.

The guest was reminded of his reading: Perrin's sky was not always cloudless, nor did every cloud have a silver lining. He called a spade a spade, at times decrying the country idyll, which his reputation ironically helps to perpetuate. The last essay in First Person Rural, "The Other Side," was one long slam at country life, in which Perrin told readers of the New York Times that, no, it was not all peaches and cream in upstate Vermont. The peaches often came canned, the cream had to be processed. This was best summed up by his Wooden Bucket Principle: "By this I mean a tendency to imagine almost anything in the country as simpler and more primitive and kind of nicer than it really is." Wooden buckets, idyll to the contrary, haven't been used for maple sugaring since the Civil War; "I like tin," Perrin quoted the secretary of the Vermont Board of Agriculture as saying in 1886.

Perrin and guest left the cows and went back over his pasture, then into the woods past the light-running spring that supplies the farm with water. They reached a back pasture Perrin had been clearing recently. "I farm about half the time," he said, "less in the winter. I try to write in the mornings, when I'm best, and farm in the afternoon. But summer reverses that the heat. I'm teaching only half time now I've an agreement with the College that I accomplish in two years what would normally be done in one. The writing and the farming fit together now, they do balance very, very well."

The education Perrin passes on in his rural writings to would-be farmers comes largely from the land, he explained. He does read some agricultural texts and other farm manuals, but most of what he's learned in 20 years has been in the field. "And, of course, Frost is a good source," he added.

The guest was again reminded of FirstPerson Rural, and that section in "The Perfect Fence Post" detailing the only right-headed thing Perrin accomplished during his fencing adventures: "The one thing I haven't done is to use white or gray birch for posts. And there it was poetry that saved me, not common sense. Long before I thought of being a farmer, I had read most of Robert Frost and could quote from 'Home Burial': 'Three foggy mornings and one rainy day/Will rot the best birch fence a man can build' it's not even much of an exaggeration." It seems, his guest thought, that Perrin's professorial career fits in nicely at times, too.

"I think I caught Frost in a mistake once," Perrin went on. "What kind of birches do you think he was referring to in 'Birches'? Right the white birch. But actually it's the much less attractive gray birch that trails its leaves 'Like girls on hands and knees that throw their hair/Before them over their heads to dry in the sun.' Still, I can't believe a farmer like Frost wouldn't know his trees." Literary license. Even if the admired poet used it, Perrin does not. The stuff of the Rural books is useful stuff, pointing the reader in the right direction. It is entertaining, too, but it is practical knowledge for one who wants it: buying a pickup truck or a chainsaw, gathering syrup or raising sheep, market research in the general store.

We came back through the woods, Perrin and guest, across the pasture and toward the house. Perrin is worried about these pastures and houses, he said. He is worried that Thetford will become is becoming a bedroom community for ever-growing Hanover. That piece he wrote in these pages six years ago detailed his original island-in-a-sea-of-emmets concept. Now, he sees the island erupting, as if volcanic, and growing larger, taking space that was once sea.

He said he doesn't feel an agricultural community can survive in America once it is compromised by other interests. "Americans want to interact. We want to be classless, and listen, I love us for it. But when the lower-class farmer is going to Rich's discount store with the people working in Hanover, something breaks down." Perrin is active at town meetings in Thetford, trying to preserve what he sees as good in the community. Initial resentment against the "Dartmouth professor" has largely passed.

Would you like lunch, he asked the guest as they neared his large garden. "This corn may not be the best in the whole world, but it's about the best I've ever had." Corn picked, we went inside.

THERE, on the modern countertop, Perrin was preparing bacon, lettuce, and tomato sandwiches, musing about First Person Rural's success and telling the story of how his publisher actually wanted a book about Japan.

"David R. Godine, the publisher, is an alumnus of Dartmouth and, at the time, I was chairman of the English Department," he said as he scooted about the kitchen, which is large enough to hold a good-sized wooden table of local maple and a smallsized wood-burning stove. "And I was dealing with Godine about someone who was trying to get a job in the department. I had this manuscript I'd found that I thought was a hot prospect. Other publishers didn't think it so exciting. But I took it out of my desk and showed it to David, and that's how Godine came to publish The Adventures of Jonathan Corncob a few years back.

"Then, actually, Godine took Giving Upthe Gun: Japan's Reversion to the Sword before he took First Person Rural. It just happened that Rural came out first. "Would you like Tab or milk?"

The guest, thinking impulsively, chose Tab, and instantly regretted this as he recalled "Real Milk" in First Person Rural: "Which brings up the last question: What does unpasteurized milk taste like? Well, like pasteurized milk, only more so. There is no question that it has more flavor, just as fresh tomatoes have more flavor than stewed ones. Or fresh lettuce than boiled lettuce."

"I must say," said Perrin, sitting down now. "I'm very proud of this lunch. Everything in it is from the garden, except the bread. And the bacon's from last year's pig. Everything except the bread is from the farm." And except the Tab, thought the guest, damning his choice but too timid to change it.

Perrin, between bites of the world's most delicious corn, talked about how First Person Rural was born. "It was an afterthought to Giving Up the Gun. I was amazed at its success. One of the facts I thought I knew was: No one buys essays, with E. B. White's being an exception.

"What drew me to this kind of writing? I think just the farm. I became a farmer and started learning things. I started really doing it the writing when Country Journal was founded in 1974. Then Walter Hard Jr., who was then editor of VermontLife, had seen things I'd done for The NewYorker and asked me to write." The "Parttime Farmer" column began five years ago.

"I was truly amazed at the success of the book."

As were others. Brian Vachon, current editor of Vermont Life, said recently, "I sure was surprised. I was pleased for him, of course, and very surprised." David Godine claims to have been a little more prescient: "I basically thought it was about time one like that succeeded."

Godine's is a small, high-class publishing house in Boston, and First Person Rural was nearly as much a breakthrough for the company as it was for Perrin. As laudatory reviews and sales orders came tumbling in, Perrin became Godine's new star. Happily, success has changed nothing. "We certainly have a cordial relationship with Ned," Godine told an interviewer. "We'll take whatever he gives us. He's one of our best writers in many ways. The most pleasant, the most engaging, the most fun."

Perrin will, of course, be pleased to hear that Godine is ready for whatever he offers. The publisher's proclamation could go a long way toward satisfying the author's penchant for dabbling in exotica.

He does write and has written about things outside the farm. Japan, for instance: Giving Up the Gun was born in 1965 when Perrin discussed in The NewYorker a curious historical footnote. During the three centuries that Japan was a closed country, from the mid-1500s until Commodore Perry's celebrated "opening of Japan" in 1854, the island's culture and tradition forced a reversion in its weaponry. The most technologically advanced gun-making country in the Eastern world gradually reverted to use of the sword, while progress marched on unimpeded in other areas of production.

Perrin's story sat for years, dismissed by Japan scholars who derided his account as uninformed since he was not of their club. "Since we don't know this and since you're not one of us, it can't be true."

So, indignant, the English professor dusted off the tale a couple of years ago, added substantiating notes and bibliographies, and threw it back in the faces of the scholars as a Godine volume in 1979. "I was determined to make them consider this," he said, noting happily that several of them now have. "Gun did amazingly well," said Godine, "for a book that didn't seem to have a wide audience. I believe it did 5,000."

There have been other things, too: an early book of essays called A PassportSecretly Green that Perrin would now like to disown; Dr. Bowdler's Legacy, called a "graceful scholarly" book in one review and concerned with expurgated books in England and America; the Corncob book, a manuscript of an Englishman's picaresque adventures in revolutionary America that Perrin chanced upon and edited; two long, thoughtful essays on Dartmouth and the Vietnam War that ran in 1968 and 1970 in The New Yorker ("those were all I could think to do to oppose the war, so I'm very glad I did them"). Taken together with the Rural books, these seem to constitute the body of work of a literary jack-of-all-trades. But look more closely: a nation's turning back the technological clock; a sardonic, amusing look at Olde days; a protest against a wasteful war far from home that was tearing apart our country and theirs. The sensibility that would harbor such interests could have been shaped on a rural Vermont farm. The writings, ultimately, seem consistent.

Beyond the congruity of the writings, there is one more thing about Perrin that is not quite as it would seem to the casual observer. He is now a sometime farmer, a full-time writer, and a half-time teacher. One could conclude that the students of Dartmouth have suffered because of his newly acquired interest and success. That is not the case.

"I've never had some sort of program for either my life or my writing," said Perrin. "Do you know Frost's 'The Road Not Taken'? 'Yet knowing how way leads on to way,/I doubted if I should ever come back.' Way has led on to way for me.

"Oh, the half-time thing is partly because of new concentrations, partly wanting some springs and summers to farm. But really it's the teaching itself. I have a theory: There are some teachers who go on indefinitely and never burn out. There is one whole class of teachers who are in effect masters who have disciples. They can go on forever. There are others who need a voyage of discovery for themselves, too, so they don't lose the freshness. I am of that class. There were days I felt I was coming much too close to just going through the motions. The half-time is better: The spring is still flowing, but just at a diminished rate."

Perrin's search for freshness goes beyond the classroom; it afflicts his typewriter as well. After five years of writing "Part-time Farmer" for VermontLife, he will close the column this winter. "Writing has never pushed me to farm. I've never felt: 'l've got to have an experience.' I never want to feel that."

Laments editor Vachon, "It is to my great regret that he's ending the column. It was just a marvelous series that came to a logical conclusion. His style is unique. I'm hoping he will keep writing for us."

He will. And for Country Journal. And about the farm. There will be a Third Person Rural, he assured his visitor, but probably not for about five years. How can he be certain another book will come out of the farm? For just that reason: The books come from the farm, just as the corn, tomatoes, and bacon do. And there is no question that he is staying on his farm.

"I can't imagine a college or a farm I would rather be at," he said. "I remember when I was at Williams [class of '49] and driving up to Vermont to buy pumpkins with fraternity brothers. We just despised the farmers. We were not even seeing them as picturesque, just dumb. Then I just got this craving to buy some land. And now. . . .

"You know, I'm in a strange position here. I'm a divorced man, and women I know all love to travel 'let's go for a weekend in New York, or a week in Europe.' I can understand that, but I only want to be here or in Hanover."

Perrin, sitting in his kitchen with his guest, was being carried away again by the idyll, that country idyll that is the heart and lifeblood of his books, but that is tempered therein by the often harsh realities of rural life and by Perrin's desire to preserve what he knows of the idyll. "Regional writing is most often the literature of converts," Perrin said. "And we converts tend to be that way: more passionate about our beliefs. I do tend to fight that impulse when I write.

"And see, if he or she is going to commit the sin of writing about it in the first place, and therefore calling attention to it, he should temper it so not everyone will come and ruin it."

We all have such tensions in our lives. Remember your favorite foliage spot when you were in Hanover? The place where, you were certain, the leaves were more beautiful each October than anywhere else in the valley? You wanted so badly to tell everyone else, but then it would no longer have belonged to you.

Perrin found a solution once, and jokingly presented it to the League of Vermont Writers when he was speaking at their meeting. "I told them they each had a moral duty to write something bad about Vermont at least once a year." That charge ignited quite a meeting, he recalls.

With its October debut, Second PersonRural should ignite a new volley of praise for its author. Since it, too, is culled from previously published articles, most from Vermont Life and from a column Perrin wrote for one year for Boston magazine, it is tried-and-true material that should succeed. Godine is confident: "It will do at least as well as the first," he says, noting that the first probably has sold 30,000 copies in its various hardcover and paperback printings, and noting further that the second has already been picked up by the Book-of-the-Month Club. Perrin himself is hopeful: "I'm not too terrified of any backlash after the first one's success. It could bomb, of course. But that would be all right, too; it was fun to do."

It will not bomb. More philosophical than the first and longer, it should certainly please the audience First Person Rural delighted. And it will probably find a larger readership among those non-farmers who perhaps found the first book a bit too instructional.

PERRIN had been talking to his visitor for a long time, and his musings were becoming more of the miscellaneous variety. He had trouble trying to define regionalism "having something to do with trees and lobsters, isolation, boundaries" but said that the current interest in regional writing has been "born of more than two parents. No one in New England can write about this without being aware E. B. White was here first. Then there was the ecological movement. And all the back-to-the-land stuff." He added that he sees Dartmouth as a back-to-the-land college. "Dartmouth consciously grew out of its regional part after World War I. And, well, Hanover's growing. But the students seem to be keeping their connections with the actual terrain of New Hampshire. I think the women feel it, too."

He was interrupted at this point by a phone call. It was a colleague from the English Department, a woman who has been teaching at Dartmouth for five years and who wanted advice about some Thetford land she'd been looking at. Perrin asked her about water and told her about the prices of septic systems these days. "How much do you love the land?" he asked. He counseled her for perhaps ten minutes, and ultimately advised against the parcel. "Unless I just had to have that particular piece of land, I would pull out." Hard-nosed realism with a dash of romance these are necessary ingredients in Perrin's rural recipe.

Returning to the table, he told his guest that the long visit should soon end. He had some wood to deliver, and the late-summer sun would set soon. Cordial good-byes were offered, and as the guest drove off toward the Thetford covered bridge, Perrin donned his jacket and prepared to deliver wood.

GOOD writers who have gained note through their writing are difficult to write about. The thought haunts you that they have said it themselves already, that the final word has been spoken. If you bring a foreknowledge of the writers' egos to Ben Franklin's autobiography or to TheEducation of Henry Adams, what point is there in choosing a mere biography instead?

And so it is in assessing Ned Perrin. Once you've read the Rural books, you feel you've found the essence of the man. The futility inherent in attempting a profile of him increases when you reach the piece's end. How can you sum up?

You give in. You go to the source for the final word on Ned Perrin. The end of "Grooming Bill Hill" reads like this: That's how 1 came to be adding eighteen acres of pasture this year. That's how come for the next half-century, at least, there will be one green grassy hill in Thetford Center, Vermont, to contrast with the dozen or so wooded ones, and a new green meadow behind it. There will be cows against the skyline, and there will be four new stone walls visible. It will be no bad legacy to leave.

Robert Sullivan '75, until recently editor of New Hampshire Profiles magazine, is nowa reporter for Sports Illustrated.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHAIR

November 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

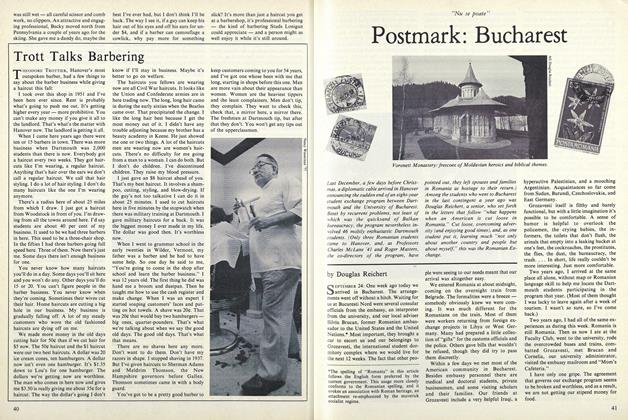

FeaturePostmark: Bucharest

November 1980 By Douglas Reichert -

Article

ArticleTrusteeship and the Alumni

November 1980 -

Article

ArticleUnofficial Arbiter

November 1980 By Patricia Berry '81 -

Article

ArticleWanted: Road-trip Messerly

November 1980 By Parker B. Smith '66 -

Article

ArticlePolicy Manager

November 1980 By M.B.R.

Robert Sullivan

Features

-

Feature

FeaturePortfolio

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1986 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBob Thebodo and Crew

OCTOBER 1997 -

Feature

FeatureAIMEE BAHNG

Nov - Dec -

Feature

FeatureThe Philosophy of Culture

DECEMBER 1966 By ALBERT WILLIAM LEVI '32 -

Feature

FeatureOut of the Amazon

MAY | JUNE 2018 By ANDREW FAUGHT -

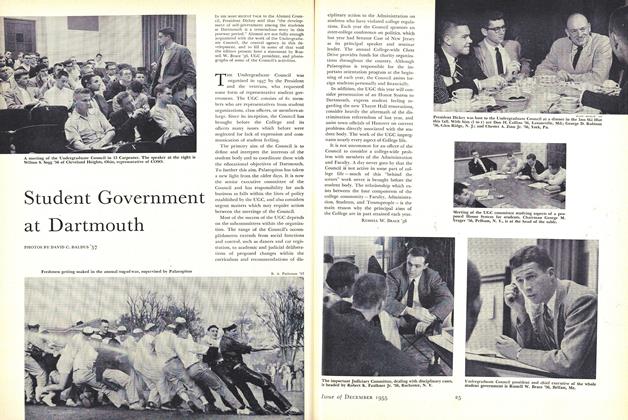

Feature

FeatureStudent Government at Dartmouth

December 1955 By RUSSELL W. BRACE '56