IT is 11:05 p.m. Photographs and dummy sheets have been relegated to the file box. In the corner of the basement plant, computer terminals, The Dartmouth's newest publishing technology, give the room a steady hum. Layout and night editors groan over headlines that don't fit and copy with copious typos, acting out the daily ritual of putting the paper to bed. Now, Ira Holmes arrives, not in any particular hurry, ready to begin his work day. His nights are made a little easier by the new equipment, and he even admits that he has become dispensable; but while others thrash over mascots and murals, The Dartmouth will hang on to another College tradition for four more years: a sometimes crusty, sometimes merry, sometimes taciturn New England compositor.

Ira Orman Holmes 11. Except for a fouryear hiatus with another local paper, the Valley News, Holmes has been composing for The Dartmouth since 1956. At 61, he rides a Honda 1000 Goldwing motorcycle as late into winter as the roads are bare, has never seen a Big Green football game, and enjoys a reputation as a stubborn Vermonter around the paper's Robinson Hall offices. He is one of two full-time salaried employees of The Dartmouth. The other is Connie Lambert, secretary-cum-bookkeeper-cum-housemother. But Holmes has seniority. He will be completing his "tenure" in four years, and the editors are pessimistic about the chances of ever finding as steady a replacement. One reason for their skepticism: Who would take on the hours? In order to put out a morning daily, Holmes arrives late at night when most people are trying to put the workday out of their heads. He paces himself to finish up by 4:00 a.m., and then he's off to West Lebanon to have the paper printed by the Valley News presses. He bundles the 3,000 copies and is back in Robinson by 7:00 a.m. to hand the lot over to the circulation department. Then home to bed to rise by mid-afternoon. Mrs. Holmes, for one, looks forward to his retirement.

Weathered senior editors nudge and wink at each other on the matter of the other consideration that is at stake in finding a successor to Holmes. At least one person closely associated with the College credits Holmes with maintaining the integrity of The Dartmouth. Jean Kemeny writes in It's Different at Dartmouth of an indirect encounter she had with him. A few years back, she apparently spoke a little too candidly with a reporter from the student paper so candidly that the editorin-chief felt obliged to call and verify her quotes. Jean Kemeny had to confirm that, yes, the quotes were accurate, but it was a reluctant confirmation judging by the relief she says she felt the next morning when what appeared in print was an abbreviated version of the interview: "Something had happened. Thank God! There was little candor; it was restrained, innocuous. Had the students gotten cold feet? No they had just forgotten the layout man, an old Vermonter with strict ideas of propriety, who had decided to excise nine inches of copy. After several decades with the paper he has become the unofficial arbiter. Now we all know where the ultimate decisions on editorial policy are made."

Holmes's memory tells him there was a four-letter word involved. He decreed it unprintable, but the trace of a wink in his eye suggests he probably enjoyed Jean Kemeny's directness almost as much as he enjoyed exercising final editing power. "It was for their own good," he says nOw. When irate editors called him on the not-so-slight discrepancy, he told them the typesetting machine had given him trouble that night. "That's the worst one I ever pulled," he admits, acknowledging that he has made other executive adjustments.

There was a time when, in Holmes's opinion, the credibility of America's oldest college newspaper was put in the hands of students with dishonorable intentions. Especially during the late sixties and early seventies, there seemed to be a proliferation of "so-called newsmen" who were more determined to get away with shoddy journalism than they were to banish it, according to Holmes. And there was a period "back ten years or so when the publishers of The Dartmouth were willing to sell the paper to outsiders. Those are hard years when you get a group that wants to make that kind of a change."

Perhaps more in those "hard years" than nowadays. Holmes considered himself a mainstay of the paper. These days, the senior directorate is back in control of editorial policy. "The situation is taking care of itself," says Holmes, adding a little ruefully, "I've relieved myself of all responsibility for editing." Holmes refers with pride to the current air of professionalism around the place, and he maintains that his most important contribution is constancy.

The closest observer of the several generations of aspiring journalists who have typed and edited their way up the ladder to senior directorate positions, Holmes recognizes an upward shift in the quality of writing and the overall attitude toward The Dartmouth the result, he says, of an increase in attention senior editors are paying to incoming reporters. "The training is superior to what we've had in the past. There were few people back then with journalism on their minds who would keep at it," he declares.

Holmes has never been a writer. An editor when he felt he had to step in, but never a writer. Born in Machias, Maine, he walked into the printing business after a five-year stint with the army. He was stationed in Portland Harbor, "mostly selling beer and cigarettes" at the post exchange. After the army he decided he needed a nice long vacation a bit longer than the two weeks he actually took. He says he grew uneasy with all that free time and went out to find a job. He trained as a press operator and has been in the business since 1946.

His baby then was a Ben Franklin cylinder press, which he describes as "a great big barrel that rolled over a lot of type and printed on a big sheet." The job of printing directories and guides proved too tiresome, so he moved down to New Hampshire and the Valley News to begin his present trade of composing and Linotyping.

Holmes moved over to the Dartmouth Printing Company on Allen Street in 1956, and it was there that he began his assignment with The Dartmouth. He grew restless over the summer months, however, when the paper was not publishing, and he did not have a daily job. After four years of working again for the Valley News, he was approached by two independent-minded '68s, Charles Schader (then president of and business manager for The Dartmouth) and Bill Green (then editor-in-chief). They were overhauling the production segment of the paper and pulling together their own plant with antiquated but serviceable equipment.

The transition in 1968 was greeted with skepticism by the College, and, according to Holmes, the administration strongly urged the paper to hire a full-time compositor, Linotype operators, and backups a safeguard to keep students from working long hours, it seems. Holmes agreed to sign on as the compositor, but as far as he knows, he's never had a backup. The few times that members of the present staff have known Ira to miss work, the publisher has doubled as compositor.

Holmes figures his job takes 12 to 14 hours a day counting the afternoons he conies in to lay out advertisements. He admits that a student with a little knowledge of how to run the equipment could do his job. That job has become a little easier. Last spring, the board of proprietors of The Dartmouth approved a recommendation that the paper purchase a computer typesetting system worth over $50,000.

Holmes has formed some firm views on the state of things at the College. Every morning for the past 20-odd years he has been the first person to read the paper and find out what is going on here.

"The strange thing about Dartmouth is we seem to have a group here, more people who want to change the world than at any other place I've ever been in my life. Nothing seems to stay the same; it's progressive. Changes at other schools have been forced on them. Here, it's a matter of choice."

Ira tells me he likes working with students. As a reporter, news editor, and, later, member of the senior directorate, I liked working with Ira, even if he was a little raspy at times. He says he misses my presence around the plant, and I thank him. Another time when we talked, he told me that there weren't enough women on the staff. The top five positions on the paper editor-in-chief, publisher, executive editor, and managing and assistant managing editors are held by men. Ira attributes the uneven ratio to a trend he's seen in the past, that an executive staff of women attracts more women and an executive staff of men attracts more men. "There's never a 50:50 situation," he says.

One corner of the plant is distinctly Ira's corner, with a light table and rows and rows of border tape hanging from the wall. Ira is standing in front of his slanted table, fitting copy, headlines, photographs, and advertisements on grid sheets for a 12 page edition of the paper. He wants to talk about his motorcycle, and he asks me if I would like to take a ride with him someday.

The motorcycle was a new hobby a few years ago. "The kids had one, and I figured that if I was going to ride theirs I might as well have one of my own." He has had only one accident: a matter of "looking one way and going another a car was parked in front of me." For its end-of-the-year present to Ira, the paper's 1980 senior directorate gave him a motorcycle suit with racing stripes to wear on cold rides from his home in White River Junction. To take a ride with Ira wouldn't be a bad thing.

Ira invites me to follow him through his routine down at the Valley News, He promises to stop at a doughnut shop on the way. I decline courteously. My eyes are beginning to resemble those of the fading editors who are still grumbling over typos and ill-fitting heads. "I'll stop by to visit soon," I say. "So long, Ira."

"Night now," he says in his New England way and turns back to his composing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHAIR

November 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureNow Let Him Praise Emmets

November 1980 By Robert Sullivan -

Feature

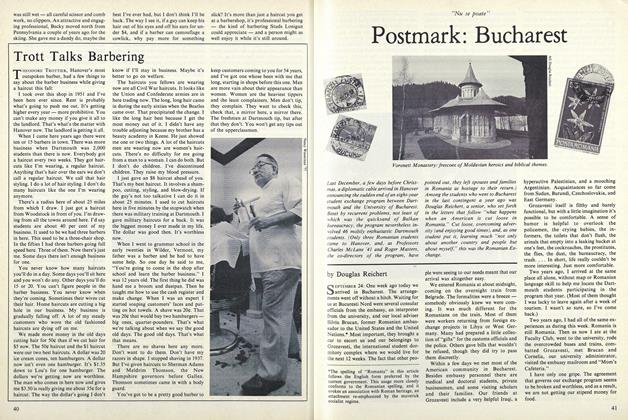

FeaturePostmark: Bucharest

November 1980 By Douglas Reichert -

Article

ArticleTrusteeship and the Alumni

November 1980 -

Article

ArticleWanted: Road-trip Messerly

November 1980 By Parker B. Smith '66 -

Article

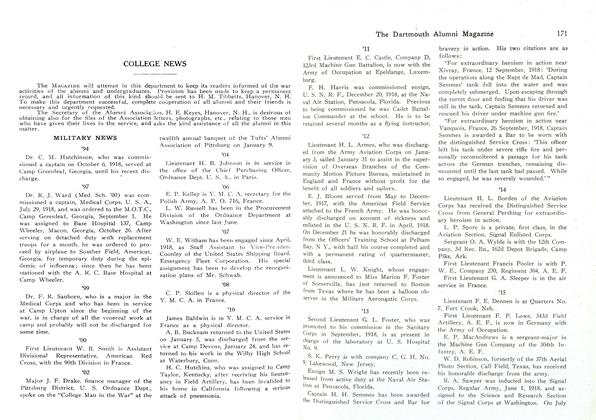

ArticlePolicy Manager

November 1980 By M.B.R.

Patricia Berry '81

Article

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NEWS

February 1919 -

Article

ArticleSINGING IN THE S. A. T. C

February 1919 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH 52 COLUMBIA 0-DARTMOUTH 7 HARVARD 2

November, 1930 -

Article

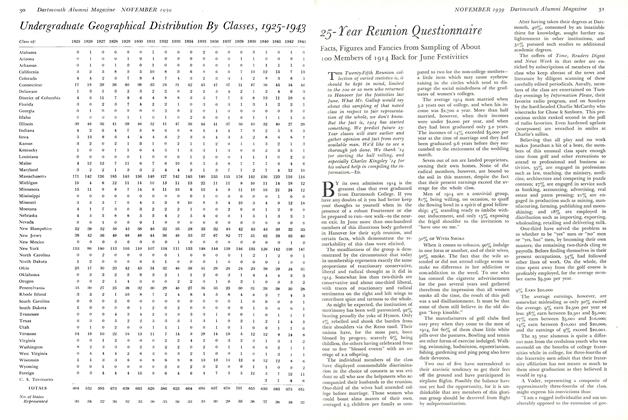

Article25-Year Reunion Questionnaire

November 1939 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Award: John Adam Graf '58

September 1993 -

Article

ArticleThen Undergraduate

June 1951 By PETE MARTIN '51