WHEN President Reagan takes the oath of office on the steps of the Capitol in January, he will do so in reasonable assurance that his administration is ready, as well as willing, to assume political power. That it is will be thanks in part to his staffs own careful planning, but also in substantial degree to transition studies made at the Institute of Politics at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government.

The irony of the western conservative getting a leg-up on his new job from the very heart of the eastern liberal Establishment is inescapable. But it is as irrelevant as is any implication of partisanship, says JONATHAN MOORE '54, the institute's director. The transition report was offered to John Anderson as well, as earlier versions had been four years ago to Jimmy Carter and, in 1968, to Richard Nixon.

"When we're not non-partisan, we have to be bi-partisan," Moore explains. "We just let them know that we're doing the study and making it available. There's no contract, no obligation. Both sides are very comfortable, and no one's getting into bed with anyone else. It's a public service, in the national interest."

The transition studies are typical of projects undertaken by the institute's faculty study groups, which draw on the not inconsiderable resources of Harvard to address specific practical problems in government or politics. Other institute activities include the fellows program, under which political practitioners spend a semester at Harvard, where they may follow their own intellectual pursuits, but must teach a study group; special projects such as television's Advocates series, training sessions for new mayors or congressmen, and conferences of presidential campaign staffs; and a students' program that offers non-credit study groups university-wide taught this term, for instance, by a former Nigerian foreign minister, a federal judge, a Boston banker, and a Harvard psychiatrist. All programs have a common mission: to strengthen the political process through more constructive relationships between the world of political thought and the world of political action.

With no faculty or students of its own, no degree-granting power, the institute functions at once as outreach one end of the two-way street between community and academy and inreach, as that arm of the Kennedy School extended to all Harvard students, complementing their theoretical curriculum with the practitioners' experience. "It's a marvelously reciprocal arrangement," the director exclaims. "I'm interested in trying to affect the relationship between theory and practice, between policy and action, between concept and operation. I like the challenge of reconciling diverse interests, issues, constituencies."

Surprisingly perhaps, Moore took English honors precisely because he planned to go into government or public service. "I didn't want to major in what I'd be doing. I could get on-the-job training for that." Once begun, the training was thorough; his direction "very deliberate, very conscious."

First he took a master's degree in public administration at Harvard, then did tours of duty with the U.S. Information Agency in Africa and India. Returning home, he became a legislative assistant to Senator Leverett Saltonstall. Next he set about learning more about the military, going to work for William Bundy at the Defense Department, in international security affairs, "the place in the Pentagon where diplomatic, security, and defense matters are reconciled." He followed Bundy to the State Department, in Far East affairs, then in 1966, "feeling too close to the war," resigned to become one of the first group of fellows at the Institute of Politics. "I wasn't sure what would happen to me if I stayed. You can get sterile, very, very defensive about the status quo."

Before his year at Harvard was up, Moore left to become foreign-affairs adviser first to George Romney, then to Nelson Rockefeller '3O in their abortive presidential primary campaigns. When Nixon won the 1968 nomination, Moore went back to claim the unused three months of his fellowship.

At this juncture began what he calls "an unintended odyssey" through the Nixon administration with Elliot Richardson, an old friend: to State, first to help Richardson settle in, then back to the Far East bureau "my second crack at the Vietnam war"; to H.E.W., after resigning from State over the Cambodian invasion; to Defense, as principal special assistant; then, finally, to Justice, where high-priority policies died aborning when "the Agnew resignation and the tapes imbroglio" became the preoccupation. Then came the Saturday Night Massacre, when Richardson resigned rather than fire Archibald Cox and Moore resigned with him. In the spring, he was appointed director of the institute and a member of the Kennedy School faculty.

Certain words "integrate," "reconcile," "reinforce," "consensus" echo and re-echo through Jonathan Moore's comments about himself and his work. He is concerned about society's ability to deal with disintegrative forces accelerating complexity, fragmentation, erosion of spiritual values. Pluralism, a political strength in itself, has become "a little bit too hyper," he argues, intensifying the fragmentation of society. "We have not, either in our political participation as individual citizens or in the way our institutions work together, discovered how to make the whole greater than the sum of the parts. Single-issue specialinterest groups are a manifestation of a tremendous, gluttonous emphasis on independence in politics. We've got to rely more on our representative institutions of government."

Independent candidacies, he contends, reflect frustration with political parties, while turning to referendum votes to bypass legislatures demonstrates an alarming zeal for simple solutions. "You take an intensely complex political issue and put it on the ballot; you oversimplify it; and you settle it with a 'yes' or 'no'. Nonsense! When you face a dangerous and scary complexity, one of the reactions is to simplify. One way is through single-issue special-interest groups; another is through a simpler form of religious expression. The fundamental, evangelical movement and its intervention into politics this year is very fascinating, very powerful and very, very scary."

"We've been spoiled by unlimited growth, unlimited resources," Moore thinks. "Now we're beginning to sense our own limitations, and we're in an unhappy mood. We're hunkering down; we're divisive. In politics, we tend to be either indifferent or alienated; we participate through grousing or watching passively on TV. We are not behaving as an engaged citizenry must for its own protection."

Moore is fond of quoting W. B. Yeats, an abiding enthusiasm since undergraduate days, to describe society's unease: "Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold." Steadfastly non-partisan, he smiles enigmatically and waves away a question as to the applicability to current politics of another two lines in the same stanza of "The Second Coming": "The best lack all conviction, while the worst/Are full of passionate intensity."

Does he share Yeats's gloom? "Operationally, I'm optimistic; reflectively, I'm pessimistic."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHAIR

November 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

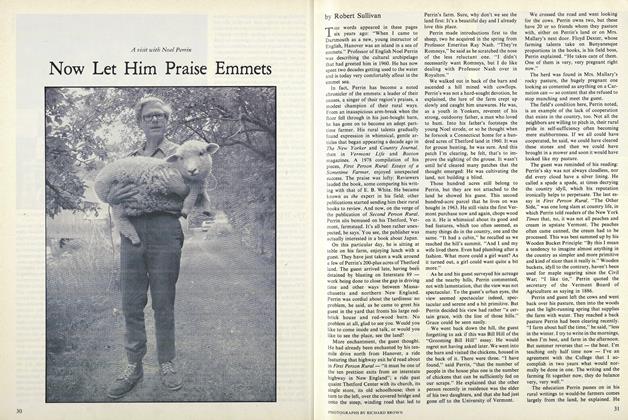

FeatureNow Let Him Praise Emmets

November 1980 By Robert Sullivan -

Feature

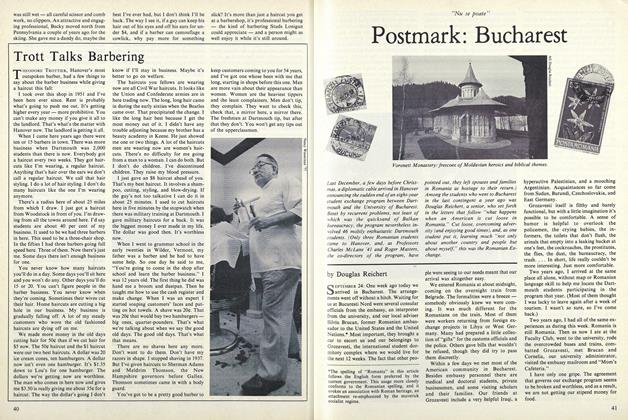

FeaturePostmark: Bucharest

November 1980 By Douglas Reichert -

Article

ArticleTrusteeship and the Alumni

November 1980 -

Article

ArticleUnofficial Arbiter

November 1980 By Patricia Berry '81 -

Article

ArticleWanted: Road-trip Messerly

November 1980 By Parker B. Smith '66

M.B.R.

-

Feature

FeatureHonorary Degrees

July 1974 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleOf Ancient Mariners... and Monsters of the Deep

September 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleEqual Opportunity: efforts to make it more equal

June 1976 By M.B.R. -

Feature

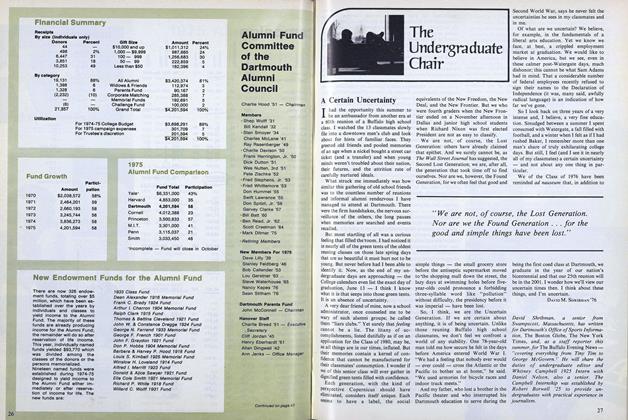

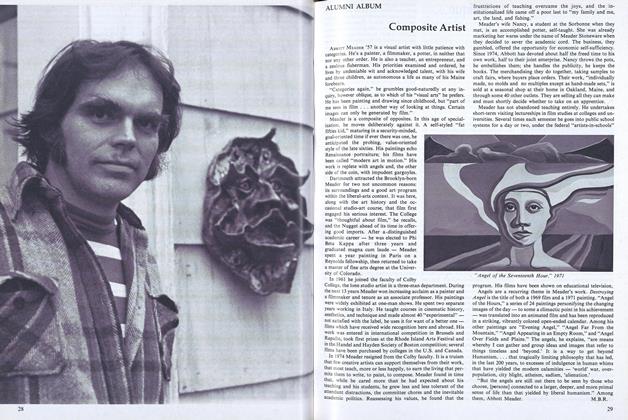

FeatureComposite Artist

February 1977 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleLiberal Learner

March 1979 By M.B.R. -

Cover Story

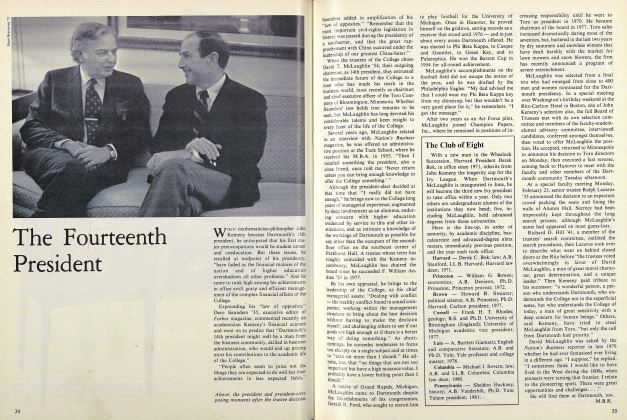

Cover StoryThe Fourteenth President

March 1981 By M.B.R.

Article

-

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT TUCKER'S RESPONSE, ACCEPTING THE NEW DARTMOUTH HALL IN BEHALF OF THE TRUSTEES

AUGUST 1906 -

Article

ArticleERNEST FOX NICHOLS

November, 1915 -

Article

ArticleTuck and Dartmouth

June 1938 -

Article

ArticleVisitor from France

January 1960 -

Article

ArticleClass of 2002

Nov/Dec 2008 By Bonnie Barber -

Article

ArticleFreshman Sports

June 1958 By CLIFF JORDAN '45