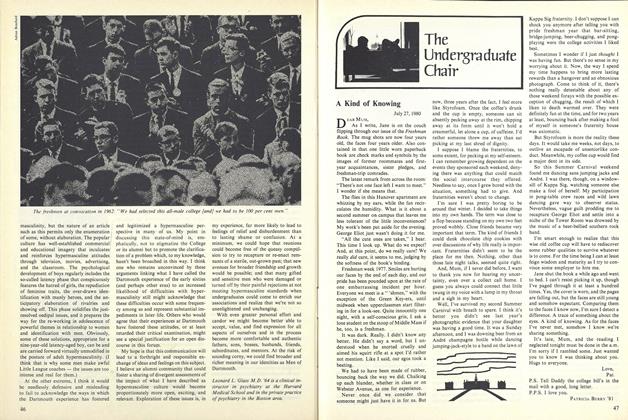

ORVILLE RODBERG has never been to Hanover. Mention Dartmouth, however, and he'll see green, all right. Orville is a real estate agent, and he's been housing Dartmouth undergraduates for years in some of the more meager accommodations West Palm Beach has to offer. Mind you, I said West Palm Beach. Connected by the drawbridge that spans Lake Worth, West Palm is light-years away from Rolls Royce-dotted Worth Avenue and the three levels of prosperity that fill the Palm Beach social roster: the riche, the nouveau riche, and the super riche.

For a term that promised to pare thick waistlines, give some color to our New England-pale skins, and provide honest labor and decent salaries, we rented from Mr. Rodberg the basement apartment at 431 Bth Street. Only after moving in did we learn the nature of our neighborhood: that we lived downstairs from a burglar under surveillance by the police and next door to a family who ignored their children riding tricycles on the local highway. Within a week of our arrival there was a double murder two blocks west of us. That day we installed a telephone and vowed never to leave anyone alone in the apartment after dark.

The good honest labor was in the employ of the Breakers Hotel, a Mobil-rated fivestar, high-society vacation complex. It used to be, at least since the inception of the Dartmouth Plan, that a contingent of 15 to 20 Dartmouth students packed bags in Hanover and headed south to the Breakers for winter- or spring-season employment, peak times of Florida tourism. According to the post-mortem remarks on file in the College's student employment office, there was a general consensus in the early years that the pay was well worth the job hassles but that taking advantage of Florida sunshine and beaches was vital to maintaining one's mental equilibrium. "This job will give you ulcers,"one student warned in his critique, while under the heading of job description another wrote "running." Beaches or no beaches, the Dartmouth contingents have been shrinking lately. Either New York City internships are more attractive options or someone is heeding the reports. Apparently, there are no applicants for next term, and the Breakers' personnel office is getting anxious.

We were forewarned, too, that waiting tables in the main dining room would be an affront to our accustomed cushioned existences, and we readied ourselves accordingly. Basically, all 12 of us, three men and nine women, dreaded every working day. We were required to work three split shifts in the six-day work week, which meant arriving in the dining room no later than 7:00 a.m., often after a 5:00 p.m. to 1:00 a.m. dinner shift the previous night. Weather permitting, we'd be on the beach by 11:30 most mornings, peeling off orange polyester uniforms, perpetually running nylons, and $9.99 J.C. Penney white shoes in exchange for swim suits, tanning lotion, and thongs.

We treated days off with kid gloves. Invariably we planned a big dinner and night of entertainment or a road trip to Disney World or Fort Lauderdale. And always there would be a few extra hours of sleep.

Given the high cost of a meal at the Breakers about $20 for dinner for one without drinks or wine no wonder we were expected to deliver courteous, efficient service, to keep our uniforms clean (for whatever chauvinistic reasons, the Breakers washed the men's uniforms free, but the women were asked to pay for and do their own cleaning), to wear hair above the shoulders and out of the face, etc., etc. While customers were always demanding and often condescending, we learned quickly to shrug off their criticisms. If we could draw them into conversation, we were far better off, as long as we didn't get too gabby. If it came up that this was just a term off from Dartmouth College, they seemed to shed a layer of affectation. I don't know why it is that people have the preconception that because someone is waiting on them, he or she must be stupid. In a way they are saying that no one with any brains would or should want to work for them.

The make-up of the staff was divided about evenly between permanent employees and "contingents." The contingents and we fell into this category were predominantly young and restless kids. Waiting tables for a term in Florida provided an interval between destinations. The real characters numbered in the other group, the full-timers. Often they were section or station captains, or at the very least waiters and waitresses who consistently brought in the largest headcounts by the end of an evening.

No one really knew what possessed him to work in a dining room, but one captain was the heir to an ice-cream fortune. Before long we realized that he was noticeably more interested in the men he worked with than the women. We never received invitations to the local nude beach. Then there was Captain Frederick, who was notoriously demanding of his staff but at the same time very protective. Once he observed a quaking waitress place a bowl in front of a particularly picky woman who had been sending food back to the kitchen during her entire stay at the hotel. He heard the woman bellow in disgust to the girl, "Is this pea soup?" Frederick, with his smoothest intonation, leaned over the woman's shoulder and said, "Yes, and isn't it di-VINE!"

At times during the eight weeks I wished I'd taken the advice of my Dartmouth predecessors who said to stay home. In retrospect, however, I value the experience. Because of working at the hotel, I'll try always to treat people with the respect they deserve. The rough neighborhood we lived in and the physical and mental strains of the job were challenges to rally for and overcome. The 11 others who entered the term with me maintain I am crazy for finding anything positive to say about the experience. Maybe so. I did come back with the best tan of my life and 15 pounds lighter. I even managed to exercise a little self-control and put aside a nice bundle of cash. But I'm fairly confident I won't be renting from Orville Rodberg again in the near or distant future.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureConjuring Ethics in the Curriculum at Dartmouth

March 1981 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

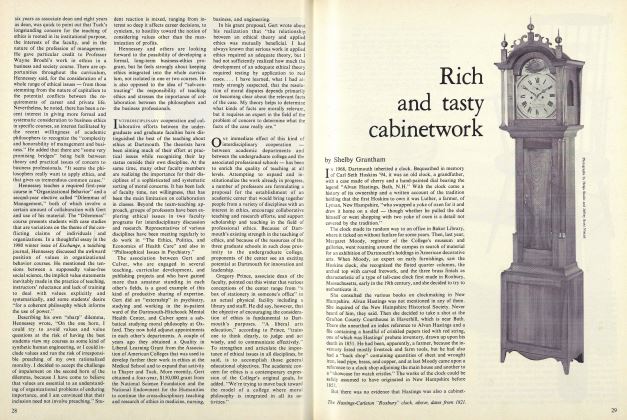

FeatureRich and tasty cabinetwork

March 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

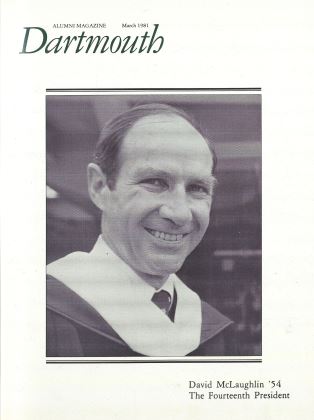

Cover Story

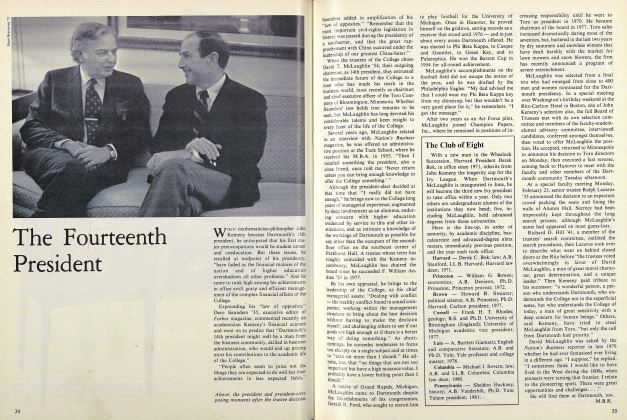

Cover StoryThe Fourteenth President

March 1981 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleImagining Beyond Limits

March 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

March 1981 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1967

March 1981 By CLEMSON N. PAGE, JR.

Patricia Berry '81

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH MAGAZINE

November, 1908 -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT NICHOLS' ADDRESS AT THE OPENING OF COLLEGE

November, 1910 -

Article

ArticlePreserving the Old Pine

August, 1912 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

-

Article

ArticlePROFESSOR GRANDGENT SPEAKS AT PHI BETA KAPPA INITIATION

April, 1925 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Election Results Are Announced

APRIL 1963