Andrew Rangell's cartoons on musical themes are a delightful marriage of two of the most prominent aspects of his personality: a consuming passion for music and an engaging sense of humor. The College's principal piano instructor and a performer of no little acclaim nationally, Rangell lives a life ruled by music but regulated by humor. The same facile fingers that dazzle music critics turn out

sophisticated New Yorkerish cartoons - a bemused gentleman showering under a blast of hot water from the bell of a French horn, a fireplace bellows rigged as a pageturning device, a balding conductor with baton raised and a pair of arms wrapped seductively around his neck.

On a cool, cloudy morning this fall, Rangell is carrying an asparagus and cheese omelet into the commons room of the Collis College Center, having just commented that the Collis snack bar is "the best thing to happen on this campus since I've been here." He explains that he keeps extremely erratic hours and likes to be able to find good food at 8:30 a.m. (which it is now) or 11:30 p.m.

As he sits down, Rangell cocks his head to listen to the discreet background music. "Good God, what is that?" he mutters about the lyrical classical strains. "It's some sort of variations on Beethoven . . . two pianos ... but who in the world could have written it . . . one of those 19thcentury composers. ..." The music ends and the dulcet tones of Morning ProMusica's Robert J. Lurtsema identify the piece as a Fantasy on Themes from Beethoven's "Ruins of Athens" by Franz Liszt. Rangell nods his head (Liszt is about as 19th-century as you can get) and takes a bite of his omelet.

Rangell returns to the subject of his erratic schedule by remarking, apropos of recent headlines about a Dartmouth staff member arrested by Hanover police for sleeping in his office, that he has more than once found himself with so little time between a late-night practice session and an early-morning class that he has rolled up in a blanket on the floor of his Hopkins Center office.

Rangell points out that to follow his normal routine of long practices, late nights, and frequent traveling he needs to stay in "extraordinarily good" physical condition. "Luckily, I don't get sick," he says, "but there are certain things I can't do because I can't risk physical injury. I avoid such sports as skiing, basketball, and volleyball very reluctantly because I have been involved in athletics from a very young age. I can't even break my left foot because the soft pedal is too important." As an extension of his interest in sports, however, he took up juggling several years ago. He had just come to Dartmouth and was "a little lonely."

Rangell is now in his fourth year on the Dartmouth music faculty, and the disarming grin with which he greeted acquaintances in the snack-bar line made it apparent he is no longer lonely although he still juggles. His official title at the College is Visiting Assistant Professor of Music, which means that he commutes regularly from Hanover to his New York City apartment and playing dates in other cities. The Hopkins Center has established a certain reputation for attracting top-notch musicians to the faculty by not overburdening them with teaching duties so they can continue to make their mark professionally. When Rangell is on campus he gives individual instrumental lessons to piano students, teaches a survey course on the piano literature, and performs frequently.

His first performance at Dartmouth, more than five years ago, led indirectly to his current position here. "One of the more continuing and fruitful of my collaborative efforts," Rangell explains, "has been with Andy Jennings," violinist of the Concord String Quartet, now in its seventh year in residence at Dartmouth. The two Andys were sonata partners as students at the Juilliard School. (Rangell transferred to Juilliard after two years in science at a Colorado school and earned his doctorate there in 1976.) So, shortly after the Concords arrived in Hanover, Rangell was invited up to perform with them. The program was heard by Gabriel Chodos, Dartmouth's resident pianist at the time. Two years later Chodos was leaving and Rangell was mentioned as a possible replacement. "When my name came up," Rangell explains with typical modesty, "Gabriel had heard me play and was . . . well ... it was just that the connection turned out to be important."

Rangell says he is "very happy" with his arrangement with Dartmouth. "The security of having a job, but the freedom of having a relatively slender time-obligation, is ideal. We live in a brutal world for...."

The thought hangs unfinished as Morning Pro Musica intrudes again. This time Rangeil is listening intently to an ad for a concert; the performer has been praised for his "highly independent fingers." "Who would that be?" Rangeil murmurs. Finally the radio announcer's voice gives the date, ticket prices, and pianist's name. "Oh, okay," says Rangeil, "I just knew it couldn't be me. My fingers are very dependent." Then he picks up the unfinished thought: "I can't imagine trading what I do for any other position. The only single thing at all difficult is that I do a rather long commute."

He goes on to enumerate the advantages of his affiliation with Dartmouth: "My connection with the particular department, my work with the Concord Quartet and with Andy Jennings, the beauty of the place, and the obvious blessing of being in an academic community." Rangeil admits that he is often frustrated, though, by "seeing

that John Updike is going to speak here just as I'm on my way to New York. But that's sort of the story of my life. I have to sacrifice a lot because of the narrowness of focus that is demanded of me." Then he hastily adds, "I don't mean to make that sound too dramatic, though."

Rangell continues by noting the stimulation of being able to perform in a great variety of settings at Dartmouth. He gives regular solo recitals that fill 900-seat Spaulding Auditorium; he combines in chamber settings with the Concords and others; he plays with the faculty-student new music ensemble, Vox Nova; he joins the Dartmouth Symphony Orchestra for concertos; and he even makes occasional appearances on the Music Department's free, informal Wednesday Noon Concert series. A particularly felicitous part of making music in Hanover, from his point of view, is "the certain ready-made audience" that the Hopkins Center has. "It's a motivated and prepared listenership," he says, "that gives you a special feeling you don't often get."

This is especially important to Rangell since he admits that his playing "takes some getting used to." Major metropolitan music critics have carried Rangell's selfassessment one step farther: He takes some getting used to, but it's worth the effort. One reviewer's early "bewilderment changed to immense admiration" as a Rangell recital proceeded. He has been described as "simply the most intellectually audacious pianist of his [young] generation." A critic who placed Rangell's playing in the genius category said, "This was playing of a quirkiness not to everyone's taste, but it was a tremendous achievement." (That review was a perfect target for Rangell's sense of humor. Instead of playing the usual publicist's game of pulling out a quote like "tremendous achievement," he suggested, tonguein-cheek, that a suitable excerpt might be "quirkiness not to everyone's taste.") And another reviewer wrote that Rangell "plays as if he has never learned the 'official' interpretations of the repertory," and then went on to place Rangell alongside such musical greats as Toscanini, saying, "Even rarer is the kind of musician who heads directly for the meaning of music with something very like the sureness of animal instinct, someone whose performing is a rage to communicate the fullness of musical experience without compromise, and damn any human limitations."

"A lot of my musical point of view," says Rangell, "came from very early exposure to recorded performances by a pianist who was one of the geniuses of the medium Glenn Gould." The iconoclastic Gould was the target of a famous quip by George Szell of the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra: "That nut's a genius." And the comparison between Gould and Rangell has been noted by more than one reviewer.

Rangell says he tries "very hard to supply the musical inspiration myself, rather than just taking orders. I try not to just be a receptacle for the ideas of some teacher." Rangell's own iconoclasm extends beyond his playing. The New York Times described him as belonging to "that new and refreshing breed of performers who combine a rigorous musical mind with an iconoclastic view of concert procedure." A student reviewer wrote in The Dartmouth, "I suspect many people actually like Rangell's dressing down rather than up for concerts, his head-lolling and liberal body English." And the same critic who placed him on a par with Toscanini described him as "a young man with bushy hair who looks like a Raggedy Andy doll that is losing its stuffing."

Rangell has long since finished his omelet, and the talk now turns to the environment that shaped his musical passion. He grew up in Colorado and "Daddy was a doctor and Mommy was a mommy." ("People do get defined in terms of what they do, don't they," he notes in an aside. "I guess that makes me a 'pianist.' ") His parents were non-musicians "not even amateur musicians" but they were music-lovers. He has three younger brothers and sisters, all of whom are, or are almost, professional musicians, too, but in the jazz tradition. Rangell hastens to define a professional musician as someone who earns "not quite enough money by playing."

He illustrates the financial point by mentioning an important concert he recently played in Washington, D.C. "It was in a lovely museum, it was reviewed in the Washington papers, and it was recorded for broadcast on Washington radio. But it provided me with less money than it cost me to get there and back," he concludes ruefully.

This leads back to his appreciation for the Dartmouth position. "This job makes all the difference. It affects my state of mind in that it provides just enough so I don't have to do anything outrageous in terms of selling my own concerts." But he says the Hopkins Center has also been "wonderful" in ways other than financial. "It's a stimulating catalyst in my work in that every time I am prepared to present something I have the opportunity to do it."

He also finds the teaching he does here "very creative and very useful. Teaching puts you in the position of having to learn. It forces me to review areas that I would not normally study. Also I like to pass on what I am enthusiastic about."

Rangell picks up his empty plate and returns it to the snack bar. On the stroll over to his Hopkins Center office to look at some of his cartoons, he points out that the cartooning is an extension of his interest in all things artistic visual as well as aural. Proving his point, the walls of his office are covered with taped-up art postcards and museum-shop prints by Courbet, Daumier, Degas, Van Gogh. And with his own cartoons.

One cartoon offers what is perhaps the definitive commentary on this warm and talented artist the ultimate marriage of his passion for music and his sense of humor. It is a self-portrait 40 or 50 years hence; captioned "A Portrait of the Artist as an Old Codger," it shows his hair thinning but still bushy, his clothes still comfortably rumpled, his grin toothless but still engaging, and his posture still Raggedy-Andyish as he sits at a piano.

ARangell

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAll the Way with J.B.A.

December 1980 By Frank Smallwood -

Feature

FeatureOnce Upon a Time

December 1980 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1966

December 1980 By RICK MAC MILLAN -

Article

ArticleMetaphysical Voyager

December 1980 By Robert H. Ross ’38 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

December 1980 By RICHARD J. GOULDER -

Article

ArticleBut Still Homeless

December 1980 By Patricia Berry '81

Dana Cook Grossman

-

Article

ArticleVox

October 1980 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Books

BooksMore Than Work

April 1981 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Feature

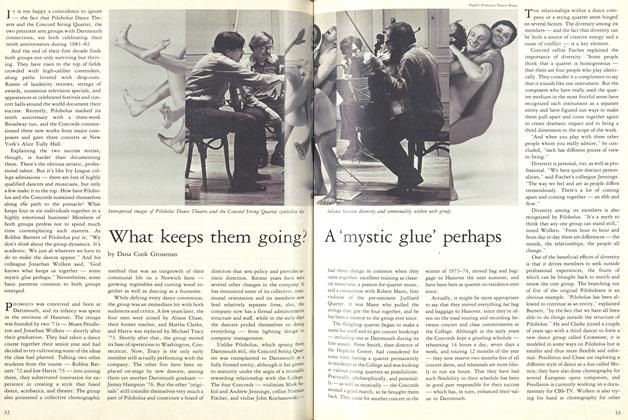

FeatureWhat keeps them going? A 'Mystic Glue' Perhaps

MAY 1982 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Article

Article"More like a house"

OCTOBER 1984 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Article

ArticleA Post-game Peregrination

OCTOBER 1984 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Article

ArticleCollege to purchase hospital buildings

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1986 By Dana Cook Grossman

Article

-

Article

ArticleFootball Tickets

October 1933 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JUNE 1972 By BRUCE KIMBALL '73 -

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL RADIO NETWORK

OCTOBER 1964 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleFRATERNITY RULES CHANGED

May 1938 By Ralph N. Hill '39 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

JUNE 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

December 1933 By S. C. H.