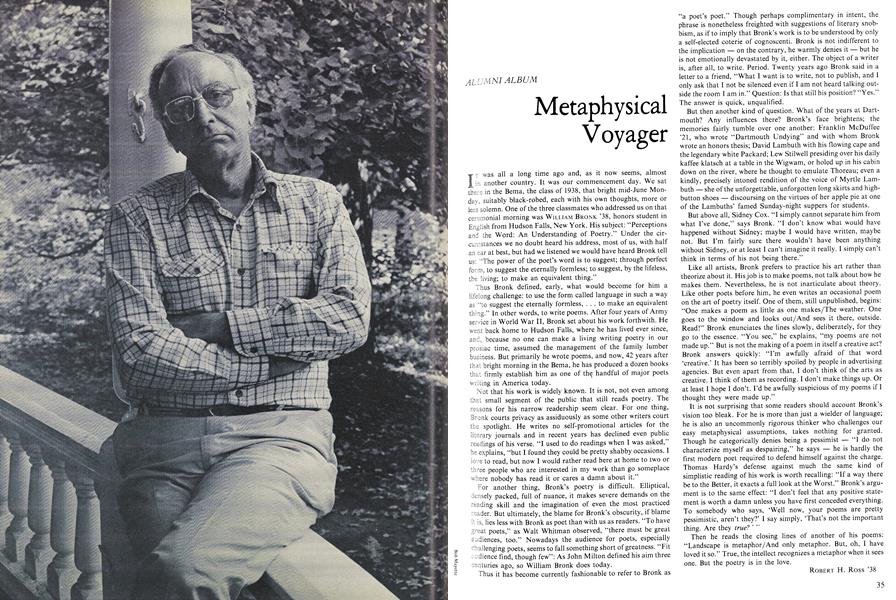

IT was all a long time ago and, as it now seems, almost in another country. It was our commencement day. We sat there in the Bema, the class of 1938, that bright mid-June Monday, suitably black-robed, each with his own thoughts, more or less solemn. One of the three classmates who addressed us on that ceremonial morning was WILLIAM BRONK '38, honors student in English from Hudson Falls, New York. His subject: "Perceptions and the Word: An Understanding of Poetry." Under the circumstances we no doubt heard his address, most of us, with half an ear at best, but had we listened we would have heard Bronk tell us: "The power of the poet's word is to suggest; through perfect form, to suggest the eternally formless; to suggest, by the lifeless, the living; to make an equivalent thing."

Thus Bronk defined, early, what would become for him a lifelong challenge: to use the form called language in such a way as "to suggest the eternally formless, ... to make an equivalent thing." In other words, to write poems. After four years of Army service in World War 11, Bronk set about his work forthwith. He went back home to Hudson Falls, where he has lived ever since, and, because no one can make a living writing poetry in our prosiac time, assumed the management of the family lumber business. But primarily he wrote poems, and now, 42 years after that bright morning in the Bema, he has produced a dozen books that firmly establish him as one of the handful of major poets writing in America today.

Not that his work is widely known. It is not, not even among that small segment of the public that still reads poetry. The reasons for his narrow readership seem clear. For one thing, Bronk courts privacy as assiduously as some other writers court the spotlight. He writes no self-promotional articles for the literary journals and in recent years has declined even public readings of his verse. "I used to do readings when I was asked, he explains, "but I found they could be pretty shabby occasions. I love to read, but now I would rather read here at home to two or three people who are interested in my work than go someplace where nobody has read it or cares a damn about it."

For another thing, Bronk's poetry is difficult. Elliptical, densely packed, full of nuance, it makes severe demands on the reading skill and the imagination of even the most practiced reader. But ultimately, the blame for Bronk's obscurity, if blame it is, lies less with Bronk as poet than with us as readers. "To have great poets," as Walt Whitman observed, "there must be great audiences, too." Nowadays the audience for poets, especially challenging poets, seems to fall something short of greatness. Fit audience find, though few": As John Milton defined his aim three centuries ago, so William Bronk does today.

Thus it has become currently fashionable to refer to Bronk as "a poet's poet." Though perhaps complimentary in intent, the phrase is nonetheless freighted with suggestions of literary snobbism, as if to imply that Bronk's work is to be understood by only a self-elected coterie of cognoscenti. Bronk is not indifferent to the implication - on the contrary, he warmly denies it but he is not emotionally devastated by it, either. The object of a writer is, after all, to write. Period. Twenty years ago Bronk said in a letter to a friend, "What I want is to write, not to publish, and I only ask that I not be silenced even if I am not heard talking out- side the room I am in." Question: Is that still his position? "Yes.' The answer is quick, unqualified.

But then another kind of question. What of the years at Dart- mouth? Any influences there? Bronk's face brightens; the memories fairly tumble over one another: Franklin McDuffee '2l, who wrote "Dartmouth Undying" and with whom Bronk wrote an honors thesis; David Lambuth with his flowing cape and the legendary white Packard; Lew Stilwell presiding over his daily kaffeeklatsch at a table in the Wigwam, or holed up in his cabin down on the river, where he thought to emulate Thoreau; even a kindly, precisely intoned rendition of the voice of Myrtle Lambuth she of the unforgettable, unforgotten long skirts and highbutton shoes discoursing on the virtues of her apple pie at one of the Lambuths' famed Sunday-night suppers for students.

But above all, Sidney Cox. "I simply cannot separate him from what I've done," says Bronk. "I don't know what would have happened without Sidney; maybe I would have written, maybe not. But I'm fairly sure there wouldn't have been anything without Sidney, or at least I can't imagine it really. I simply can't think in terms of his not being there."

Like all artists, Bronk prefers to practice his art rather than theorize about it. His job is to make poems, not talk about how he makes them. Nevertheless, he is not inarticulate about theory. Like other poets before him, he even writes an occasional poem on the art of poetry itself. One of them, still unpublished, begins: "One makes a poem as little as one makes/The weather. One goes to the window and looks out/And sees it there, outside. Read!" Bronk enunciates the lines slowly, deliberately, for they go to the essence. "You see," he explains, "my poems are not made up." But is not the making of a poem in itself a creative act? Bronk answers quickly: "I'm awfully afraid of that word 'creative.' It has been so terribly spoiled by people in advertising agencies. But even apart from that, I don't think of the arts as creative. I think of them as recording. I don't make things up. Or at least I hope I don't. I'd be awfully suspicious of my poems if I thought they were made up."

It is not surprising that some readers should account Bronk's vision too bleak. For he is more than just a wielder of language; he is also an uncommonly rigorous thinker who challenges our easy metaphysical assumptions, takes nothing for granted. Though he categorically denies being a pessimist "I do not characterize myself as despairing," he says he is hardly the first modern poet required to defend himself against the charge. Thomas Hardy's defense against much the same kind of simplistic reading of his work is worth recalling: "If a way there be to the Better, it exacts a full look at the Worst." Bronk's argument is to the same effect: "I don't feel that any positive statement is worth a damn unless you have first conceded everything. To somebody who says, 'Well now, your poems are pretty pessimistic, aren't they?' I say simply, 'That's not the important thing. Are they true?

Then he reads the closing lines of another of his poems: "Landscape is metaphor/And only metaphor. But, oh, I have loved it so." True, the intellect recognizes a metaphor when it sees one. But the poetry is in the love.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAll the Way with J.B.A.

December 1980 By Frank Smallwood -

Feature

FeatureOnce Upon a Time

December 1980 -

Article

ArticleQuirkiness to Taste

December 1980 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1966

December 1980 By RICK MAC MILLAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

December 1980 By RICHARD J. GOULDER -

Article

ArticleBut Still Homeless

December 1980 By Patricia Berry '81