Only in Vermont

I left Hanover as soon as my class was over and headed south on Interstate 91. It was only mid-afternoon, but the sun was already edging below the Vermont hills. Monday, October 27, 1980: Only a week to go until the presidential election. My destination was WVPR, the Vermont Public Radio station in Windsor, where I was scheduled to represent John Anderson in a statewide debate with the Vermont coordinators for Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan. Although my car was purring along smoothly, I was running out of gas - physically, emotionally, and psychologically. The radio debate marked the closing leg of a very long haul, almost 20 months of frenzied activity that had encompassed the New Hampshire presidential primary, the Vermont primary, and, during the Vermont summer election campaign, an unexpected stint as Anderson's stand-in nominee for vice president.

It all began quite innocently in March 1979, when a friend called from Washington and invited me to have dinner with Congressman John B. Anderson of Illinois, who was planning to visit Hanover in an effort to drum up some early support for his presidential bid in the New Hampshire primary. I didn't know much about Anderson, but after checking out his voting record in some congressional documents, I became sufficiently interested to join him at the Hanover Inn.

We gathered at a comfortable table in the main dining room four local Republican leaders, yours truly from the Dartmouth Government Department, a newspaper reporter from Anderson's home town of Rockford, Illinois, and the congressman himself, white-haired, bespectacled, looking scholarly. After about 30 minutes of inconsequential chit-chat, the waiter brought our dinners. I was seated next to Anderson, and, just as we were about to dig in, I asked him why he was running for president and what he hoped to accomplish if elected. My inquiry had an immediate, incredibly catalytic impact. Anderson put down his fork and launched into a lengthy discourse on a host of domestic and international issues, rattling off facts and figures on an astonishing range of subjects. He expressed himself with such clarity, vigor, and intelligence that I was flabbergasted. I was also worried about his roast beef and broccoli, which were growing cold and soggy on his plate, but there was no stopping him as he outlined his policies on civil rights, the need to encourage capital investment, the Middle East situation, and a variety of other topics.

Following dinner (which I enjoyed but Anderson never finished), the assembled group went out to the Hayward Lounge to offer our collective good-bye. I lingered behind in order to tell Anderson that I would be glad to work in Hanover on his New Hampshire primary campaign. He was delighted, and indicated he would be in touch with me. I realized that this could turn out to be a lonely ordeal since the only political leader I knew in New Hampshire who had announced for Anderson was Malcolm McLane '46, a member of the Governor's Executive Council. But Anderson impressed me as being a very unusual candidate. I was pleased when he sent me a letter in early June appointing me to his national advisory committee.

We spent the summer of 1979 engaged in strategic planning. Anderson's basic strategic problem in New Hampshire was all too obvious. Virtually nobody in the state had ever heard of him. In political science jargon this is known as a "namerecognition" factor. Since a Gallup poll released in mid-July indicated that Anderson had only two per cent support among Republicans throughout the nation, we concluded he would do very well if he could capture "one of the top three spots" in the primary (political shorthand for "finish third"). We figured he would need about 15,000 votes to achieve this objective.

In mid-September, Liz Hager, his New Hampshire campaign director, called to advise me that Congressman Anderson would make his first official visit to Dartmouth on Wednesday, October 3. I told her that I would line up the College Young Republicans to sponsor his talk. Political life is full of little surprises. A check of the new 1979-80 edition of the Student Handbook indicated that there were no young Republicans at Dartmouth. I reread the Handbook with growing dismay:

COLLEGE REPUBLICANS

The purpose of the Club is to promote better understanding of the Republican Party and to encourage participation in the political process. Members enjoy speakers and other events.

Officers;

No students were listed. What a dynamic group. How do they encourage participation in the political process if nobody participates? The implications were clear. I would have to arrange Anderson's first triumphal entry into Hanover. Professor Bob Nakamura, a sympathetic colleague in the Government Department, joined me in sending out 100 letters to our friends on the faculty, administration, and staff in an effort to drum up an audience. We enjoyed a shot-in-the-arm when Wendy Stone 'B2 got wind of the visit and wrote a nice front-page article in The Dartmouth, complete with glowing quotes from Nakamura, Smallwood, and Professor Roger Masters, another Government Department supporter of Anderson. A few students began to stop by my office to offer their help. One of them, who told me he had dropped out of college during the Vietnam turmoil and was now back finishing his degree, volunteered to make posters for the Anderson visit, indicating that he had drawn a lot of posters for SDS protest rallies in the late 1960s. I was a little nervous about this, but beggars can't be choosers. The two of us spent a lot of time kneeling on my office floor with Magic Markers and large sheets of cardboard.

My new friend's publicity efforts paid off. Anderson arrived in Hanover on a gray, rainy evening, accompanied by his wife Keke, two campaign aides, and his ever-present press entourage (the solitary newspaper reporter from Rockford, Illinois). I was delighted when over 200 people showed up in 105 Dartmouth Hall to hear him deliver his famous 50/50 speech - a 50-cent increase in the gasoline tax to promote energy conservation coupled with a 50 per cent reduction in social security payroll taxes. Anderson's remarks were greeted with enthusiastic applause, and I invited the audience over to Silsby Hall to meet "the next president of the United States" (more applause and a few whistles). Over 20 students signed up to work for Anderson, and one of them, Steve Kroll '81, became so interested that he decided to devote his winter leave term to driving Anderson around New Hampshire during his primary campaign. Dave Frankel '79, a reporter for the television station in White River Junction, gave Anderson a very helpful TV interview. Both WDCR and the local press also gave Anderson top coverage. What a relief. There was only one foul-up in the entire visit. It was fall foliage season, and the leaf peepers had booked up every hotel and motel within 50 miles of Hanover. Although my wife Ann was away at a conference, I figured I should invite the entire Anderson party over to the house to bed down for the night. When Ann returned home after the conference, I took her into our bedroom and exclaimed, "John Anderson slept here!"

PHASE II of my involvement in the Anderson campaign began in early December when I received a letter from the Vermont Republican State Committee listing me as the "contact person" of Anderson's Vermont primary campaign. I was really caught off guard on this. Most of the candidates - Baker, Bush, Connally, Crane, Reagan - had tons of staff: chairmen, co-chairmen, finance chairmen, campaign directors, executive directors, and numerous minor dignitaries. There I was all alone as Anderson's state contact person.

I called the Republican headquarters to find out what was going on. They quoted an article in the Burlington Free Press: "Anderson has the support of Representative James Jeffords and former State Senator Frank Smallwood of Norwich and practically nobody else in the Vermont GOP." Since Congressman Jeffords was in Washington, headquarters had decided to list me as the state coordinator through a process of elimination.

I was annoyed but not overly concerned. At that point Anderson was not even entered in Vermont, although I had told him I thought he could do well since the state has an open primary and I felt he could pick up independent votes. His campaign coffers were so low, however, that he was reluctant to enter another primary; so Christmas break passed and he still hadn't made a decision on this.

In early January, Anderson jumped into the Vermont primary. I agreed to hold the fort until they could send up some full-time staff people, but I told his national campaign organization they would have to establish a state organization fast because I was already overcommitted with the New Hampshire primary plus a full-time teaching job at Dartmouth. They said they would try to send some help, but this was still a low-budget effort without a big campaign war chest.

All was relatively quiet for the next few days. Then came the lowa debate, which catapulted Anderson out of obscurity. The next two months were utterly chaotic. People from every nook and cranny in Vermont called our house for campaign buttons, bumper stickers, brochures, instructions on what they should do. Checks made out to the Anderson-for-President Committee began to arrive in our mail box. I called the national headquarters in desperation and pleaded with them to send somebody (anybody) up to Vermont pronto. They responded that help was on the way. Mercifully, one full-time staff member, Bill Glew, showed up a few weeks before the primary to open up a one-room office in Burlington. Although the other Republican candidates were talking about momentum, it was obvious Anderson's campaign was rolling. A week before the New Hampshire primary, he made his second visit to Hanover. There wasn't any problem drumming up an audience for this one. We scheduled his speech for Cook Auditorium, but the entire lobby of Murdough Center was so jammed 15 minutes before his appearance that many people couldn't get in to hear the candidate. At the end of Anderson's speech, a group of optimistic students began to chant, "All the way with J.B.A!" It was really wild.

Anderson received 14,483 votes in the New Hampshire primary, just about what we had hoped to get in our July planning projections. But our prediction of the total turn-out was low, and he finished fourth rather than third. Still, his New Hampshire performance was good enough to thrust him into the Vermont and Massachusetts primaries, which were scheduled for the following Tuesday, March 3. Anderson lost the two states by a whisker, but his very strong 30 per cent second place finish in both primaries moved him onto the center stage of the national political arena. He lost Vermont to Ronald Reagan by less than 700 votes, and I felt pretty good about the entire effort. Representative Jim Jeffords called me, and I agreed to run as a Vermont Anderson delegate to the Republican National Convention six months hence. For the time being, I was very relieved that the primaries were over. I was scheduled to teach in the Government Department off-campus program in Washington, D.C,, and I was looking forward to a relatively quiet spring term.

Phase 111 of my involvement in the Anderson campaign began after I returned to Hanover from Washington in June. During the spring, Anderson had an- nounced his independent candidacy for the presidency, and he was busy trying to get on the ballot in all 50 states despite considerable harrassment from the Democratic National Committee.

I was away for the afternoon when the phone call came, so Ann took the message. She was pretty agitated when I finally showed up for dinner. "Sit down and brace yourself," she greeted me warily. "The Anderson people called you this afternoon. They want you to run for vice president."

"Vice president of what?" I gave her a puzzled look.

"Vice president of the United States!" she exclaimed. "But only in Vermont and only for the summer. It's all very complicated. Anderson is trying to get on the ballot, and the secretary of state has ruled he needs a running-mate in order to circulate petitions for his signature drive. They want you to serve as the stand-in candidate until Anderson designates an official nominee later this summer. You're supposed to call Jeff Taylor in Rutland. He's a lawyer who is trying to organize this. It's very confusing."

After numerous telephone conversations with Jeff Taylor and many other operatives on the Anderson staff, it became clear that it was legal for me to run in Vermont as temporary candidate for vice president of the United States; and, although the campaign wouldn't be arduous (!), the Anderson staff hoped I could do some speaking, fund-raising, and signature-collecting throughout Vermont. We agreed to hold a press conference in Montpelier on Monday, June 23, to launch Anderson's Ver- mont campaign.

On Sunday morning, June 22, I was sitting in St. Barnabas Church in Norwich during the annual visit of the Episcopal bishop of Vermont. In the middle of the service, the bishop, radiant in his vestments, strolled down the aisle to greet the congregation ("the peace of the Lord be always with you"). When he reached me, he smiled, extended his hand, and boomed out, "I'm delighted you are running for vice president of the United States. I heard the news on the car radio this morning during my drive down from Burlington." Everyone looked at me in shocked silence. So much for the secrets of state. I smiled back at the bishop and responded, "Peace."

Once the Montpelier press conference was over, I became a kind of local celebrity, at least in Norwich, where I was also the subject of historical controversy. The next morning, an elderly woman greeted me effusively in Dan and Whit's

general store: "Oh, I'm so excited! I think it's wonderful. Vermont's first vice president since Calvin Coolidge. I cast my first vote for Harding and Coolidge in the 1920 election. It will be a pleasure to vote for you." Another old-timer shook my hand: "Congratulations you'll be the third vice president from Vermont. And both of the others, Calvin Coolidge and Chester Arthur, went on to become president. Great things are in store for you!" At this point a third bystander entered the discussion: "No, no, Professor Smallwood will be the fourth vice president from Vermont. There was Arthur and Coolidge, plus Levi P. Morton, who served under President Benjamin Harrison from 1889 to 1893. Professor Smallwood will be Vermont's fourth vice president, but that's still quite an honor."

It was impossible to explain that I really wasn't running for vice president, so on this optimistic, if confusing, note I pitched into the summer campaign. It turned into a maze of radio and TV talk shows, local fund-raising speeches, and, most of all, "grass-roots" organizational meetings in small towns such as Royalton, Tunbridge, and Londonderry.

By early July, Anderson's miniscule Vermont organization began to fall into place. Bill Glew returned to Burlington as the full-time director of the state campaign. A young Yale graduate, class of 1979, he had deferred his admission to the University of Virginia Law School to work as an Anderson field coordinator. His assistant, Margaret Bullitt, was an even younger Yale student, class of 1983, who had taken a leave of absence after her freshman year to work for Anderson. A third member of the team, temporary vice presidential candidate Frank Smallwood, Dartmouth '51, was joined by three other Vermonters who ran as Anderson's delegates for the electoral college: State Representative Susan Webb of Plymouth, State Representative Chester Ketcham of Middlebury, and my legal adviser, Jeff Taylor of Clarendon. Since I was the only one of the six who spoke for a living (in the classroom, that is), the others looked to me to serve as Anderson's surrogate orator-in-residence.

During the summer, Anderson's volunteer organization grew to a point where we were able to open field offices in Bennington, Brattleboro, Rutland, and Londonderry. In late August, Anderson designated Patrick Lucey as his national vice presidential nominee, and I submitted my formal resignation to the Vermont secretary of state. However, the non-stop workload continued for all of us throughout the fall campaign, which was highlighted by Anderson's visit to Burlington in late September, plus other state visits by Patrick Lucey, Keke Anderson, and national campaign coordinator Mary Crisp.

In retrospect, the Vermont campaign was reasonably successful. We collected more than 5,000 signatures to place Anderson's name on the ballot; we raised over $50,000 in contributions, which we forwarded to the national headquarters in Washington; and, most important of all, we helped Anderson gather 31,761 votes in the presidential election, which gave him 15 per cent of the Vermont total and tied us with Massachusetts for the highest percentage of support in the nation. Since the Vermont turnout was the largest in the state's history over 200,000 I think we got a lot of voters to the polls who wouldn't have participated otherwise. Yet, when all was said and done, Anderson didn't win Vermont, or any other state, as Ronald Reagan was swept into the White House on a tide of electoral votes.

WHAT did I learn about the political process in general and third party (and independent) candidates in particular as a result of all of this? The first and most obvious lesson is that there are massive institutional obstacles that make it very tough for any outsiders to crack the twoparty system. In Anderson's case he was forced to deal with a series of difficult legal battles in many states even to get his name on the ballot. He needed to develop a national party platform while dealing with all the details involved in establishing a campaign organization that the major party candidates take for granted. He also faced chronic financial problems.

His most basic problem of all, however, was dealing with the awesome challenge of psychological perceptions, a problem which has been magnified by the advent of public-opinion polls and the modern media campaign. The basic scenario runs as follows: The more time a minor-party candidate spends on fund-raising and organizational work, the less time he has for exposure and visibility (especially on television). The less exposure, the harder it is to get anywhere in the polls. The lower the standing in the polls, the less media

coverage (especially on television). The less media coverage, the lower the campaign contributions and volunteer support. All of which leads to more time spent on fundraising and organizational efforts, and the whole wild downward cycle starts all over again. It becomes a self-denying prophecy, and it is extremely difficult to reverse.

The bottom falls out once the candidate loses "credibility" and is perceived to be a loser. During the last four weeks of the campaign, I became more and more frustrated trying to deal with an endless stream of confused voters who liked Anderson and didn't like Carter (or Reagan), but were scared a vote for Anderson was a vote for Carter (or Reagan), and hence were going to vote for Carter (or Reagan) whom they didn't like because they were afraid to vote for Anderson whom they did like. After listening constantly to this kind of tortured pleasurepain calculus, I met a woman at a rally in Springfield who marched up to me rather belligerently and explained that she was going to vote for Libertarian candidate Ed Clark (class of 1952) because she thought he made the most sense to her. I grasped her hand and exclaimed, "Good for you! I'm delighted to meet someone who is supporting the candidate they believe is best qualified for the job." Unfortunately, she was something of a rarity. I met an awful lot of unhappy voters who were engaged in what election analyst Richard Scammon calls the collective "October syndrome of chopping off No. 3."

Hence, Anderson and Ed Clark and all other minor-party candidates faced a very difficult series of institutional and psychological barriers deeply ingrained in the American two-party tradition. In addition, I think Anderson made some major mistakes in his campaign. I realize it is easy to second-guess, but I wish some things had happened differently. First, I think Anderson got started much too late. Second, when he did get his big break in the debate with Ronald Reagan, he came off as very well informed but too intense, too preachy, and even too shrill for my own tastes. Third, and most important in my opinion, he made a very major and very questionable strategic decision when he hired David Garth as his de facto campaign manager. Garth, who is the modern media politician personified, decided that virtually all of Anderson's very limited resources should be expended on one roll of the dice a big-state television saturation effort. As a result, Anderson devoted less and less of his resources to precisely the kind of volunteer organizational effort we were trying to launch in Vermont. Admittedly, Vermont has only three electoral votes, but Anderson had done very well in the primary with virtually no expenditures. Unfortunately, we continued to receive peanuts from headquarters during the summer and fall. To be precise, Bill Glew was paid $100 a week, Margaret Bullitt was paid $50 a week, and we spent a nominal amount on mailings, telephone calls, and rent for our one-room office in Burlington. Finally, during the last two weeks of the campaign, we received a couple of thousand dollars for radio spots and newspaper ads, but by then it was too late. As Curtis Gans wrote in the Boston Globe, Anderson was "Garthed." In Gans' words, "Garth's plan depended solely ... on his advertising genius, should the money be available to pay for his ads.... By the time Anderson put forward his thoughtful platform and appeared in debate with Reagan, Anderson had slipped 10 points in the polls, the money for his campaign and Garth's ads had stopped arriving, and the 'Anderson difference' was gone."

Yet, despite its shortcomings, Anderson's campaign impressed me as being a remarkable effort. He didn't win any states, but he did receive over 5.5 million votes or 7 per cent of the national total, which qualified him for federal matching funds. He also expressed the kind of innovative ideas that could lead to a very important future role in American politics. Where will Anderson go from here? I'm not sure, but I suspect that we haven't heard the last from John B. Anderson of Rockford, Illinois.

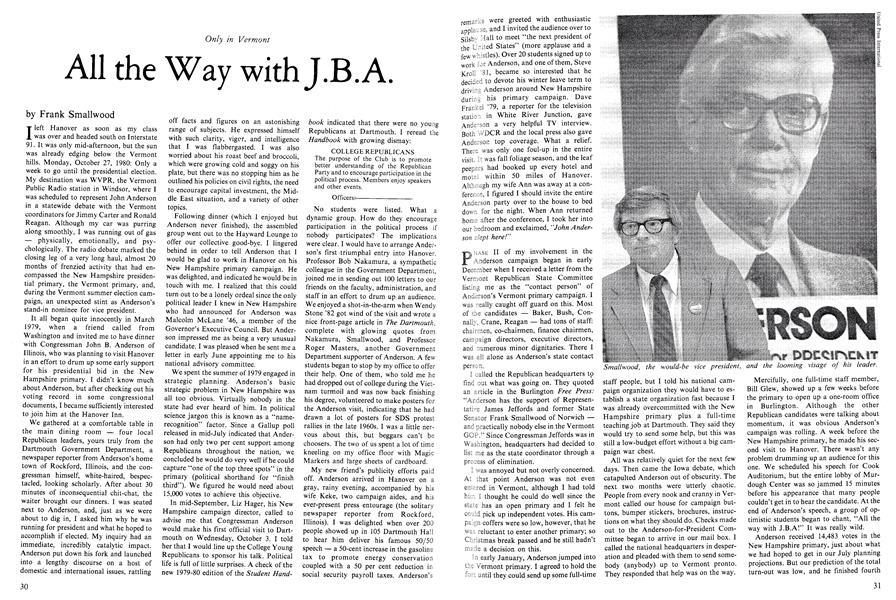

Smallwood, the would-be vice president, and the looming visage of his leader.

Variously special assistant to PresidentDickey, professor of government, head ofthe Policy Studies Program, dean and thenvice president for student affairs, FrankSmallwood '51 has been described as theElliot Richardson of Dartmouth College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOnce Upon a Time

December 1980 -

Article

ArticleQuirkiness to Taste

December 1980 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1966

December 1980 By RICK MAC MILLAN -

Article

ArticleMetaphysical Voyager

December 1980 By Robert H. Ross ’38 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

December 1980 By RICHARD J. GOULDER -

Article

ArticleBut Still Homeless

December 1980 By Patricia Berry '81

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThayer School Report

April 1941 By F. H. Munkelt '08 (Thayer '09) -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCAN WE TALK?

MAY 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureSUBJECT: HALF OF HUMANITY

June • 1988 By Karen Avenoso '88 -

Feature

FeatureDefining the Engineer

NOVEMBER 1962 By R.J.B. JR. -

Feature

Feature"These Children Are the Future"

MARCH • 1987 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureHeeding the Beat of a Different Drummer

SEPTEMBER 1987 By Teri Allbright