The trustees' decision last month to raise the goal of the Campaign for Dartmouth from $160 to $185 million came as a shock to practically no one, if only because no one would reckon to buy anything this year for a price set in 1977.

Nor is Dartmouth unique either in its drive to raise capital sums that would have seemed astronomical even a decade ago - the Third Century Fund aimed at $51 and raised $53 million in the three years before 1970 - or in coming back to the trough to counteract erosion of the dollar's worth. Both Dartmouth's original goal and its 15.6 per cent increase are relatively modest.

Yale has recently oversubscribed a $370-million goal, and Stanford surpassed its $300-million target. Princeton had wound up a $125-plus-million campaign shortly before Dartmouth's started, and last year Harvard, in the first of a five-year campaign, raised $80 million toward a $250-million goal through selective preliminary fund-raising. Notre Dame, running about a year ahead of Dartmouth on a roughly parallel course, set an objective of $130 million, raised it to $166 million after three years, and is closing out a five-year campaign six months early with $172 million in hand or pledged.

Far from being surprised at the trustees' action, most Dartmouth alumni we talked with last month, in a thoroughly unscientific random sampling, considered their raising the campaign's sights completely justified.

"It was not only a very legitimate move but a very necessary one," said William Clay '37, a Mount Sterling, Kentucky, attorney, who is "more familiar than the average person perhaps" with the problem in his capacity as a member of the executive committee of Transylvania University in Lexington, which is, like all private institutions, facing the same inflationary pressures.

"They had to do it; it was only realistic," said Samuel Pratt '41, English Department chairman at Ohio Wesleyan, which has recently raised its own capital-campaign objective by a similar percentage. "I heartily approve, particularly since there's a strong emphasis on endowment rather than bricks and mortar."

Peter Bogardus '51, a San Francisco stockbroker and area vice chairman for the campaign, is enthusiastic about the prospects of success. "There's no question they should have done it," he said of the trustees' action. "When we're where we are when we are, there's no reason not to up the goal." Bogardus added that a friend of his involved in the Stanford University campaign reported "a ballooning effect toward the end." He foresees no problem with the amount of the increase, which he characterizes as "just perfect," or in meeting the new objective. A lot of donors, he thinks, have delayed their giving "it's just human nature" and the new goal with the same deadline should effectively challenge the volunteers.

Susan Bull Riley '77, a musician who teaches at a private school in Maryland, finds little personal relevance in the change. "That kind of money is so far out of my ballpark that I really can't conceive of the difference." She's sure the increase is necessary, but she wonders sometimes, she said, "about whether the money is spent all that wisely. The student center, for instance I can't believe something that fancy was necessary." She would rather have seen the money spent on "good faculty and helping poor students."

To learn more about Notre Dame's successful campaign, we talked with James Frick, the university's vice president for public relations and development and a 30-year veteran of its fund-raising efforts.

"With the campaign going so well [they were already over the objective three years into a five-year campaign], we figured what inflation had been since the goal was announced and simply added that on," Frick reported. Alumni reaction to the change was very positive, he said. "We showed them how inflation was hurting what we had accumulated; how, for example, the last residence hall we had built, in 1973, cost $3.4 million, while the one currently under construction was costing $7 million."

Was he optimistic about it at the time? "Absolutely!" Frick declared. "We still had 250 to 300 prospects in the $25,000-to-$100,000 range that we hadn't contacted yet." His optimism was more than justified, as Notre Dame's alumni as legendary in their loyalty almost as Dartmouth's oversubscribed the revised goal. Lay alumni gave an average of $1,998 to the campaign, with 85.7 per cent participation. "The reaction from the professors was tremendous," Frick added, with a total of $652,330 raised from a faculty of 643.

Notre Dame was winding down its campaign six months early, with receipts at $172 million at mid-November. "We want to restore emphasis to the alumni fund and start initial groundwork for the next campaign, which will probably start in 1983 or 1984," Frick explained. He's already been through four capital fund drives. "There's no end to it," he conceded, "but there can't be if you're going to keep up."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAll the Way with J.B.A.

December 1980 By Frank Smallwood -

Feature

FeatureOnce Upon a Time

December 1980 -

Article

ArticleQuirkiness to Taste

December 1980 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1966

December 1980 By RICK MAC MILLAN -

Article

ArticleMetaphysical Voyager

December 1980 By Robert H. Ross ’38 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

December 1980 By RICHARD J. GOULDER

Article

-

Article

ArticleLIBERTIES ENDANGERED

April1935 -

Article

ArticleAt the annual meeting of the Dartmouth

December 1960 -

Article

ArticleCarnival Poster Anyone?

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Article

ArticleTHE SCORES

December 1979 -

Article

ArticleA Little Ski Award

December 1989 By Dick Jackson '39 -

Article

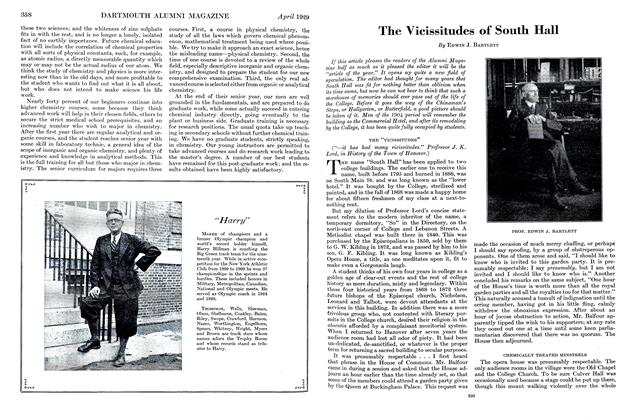

ArticleThe Vicissitudes of South Hall

APRIL 1929 By Edwin J. Bartlett