ON THE VERGEby Dikkon Eberhart '68Stemmer House, 1979. 215 pp. $9.95

On the Verge is aptly named. For it's a novel the author's first that's on the verge of being better than it is, on the verge of showing us that Eberhart will probably write better stuff than what he's done here. I don't mean to denigrate this novel. It's a promising work that shows a wide range of talent. But like many first novels, it suffers from what usually plagues first-time novelists: a penchant for the melodramatic, a predictability of plot, a propensity to introduce stock characters, and a leaning toward self-gratification in "message." As a promise of things to come, the author has a fine ear for dialogue, a good sense of plot, a better-than-average ability to create character, and an undeniable affinity for the kind of lyricism that at moments turns the novel more toward poetry than prose.

The plot is out of the late 1960s. The narrator is Noah, a kind of Henry David Thoreau in a down vest who has fled the crimp of city life with all its usual complicated and civilized allurements to take up the mason's trowel and the carpenter's hammer in Vermont. There, between his vegetable gardening and solitary woodland ramblings, he meets and eventually works for a band of part-time expatriates from Boston. As long as Noah tends to his garden, his woodpile, and his masonry he does just fine, but in this novel the Garden gets peopled. And when that happens, Noah's perceptions and values get spaded under.

There are at least two pests here: Jill, the wife of Robert (for whom Noah is building a house), and Lauren, the rather obtuse wife of a city scholar. Jill emerges as the narrator's ego. If there's an alter-ego in the novel, then that's Lauren. It takes a death in this woodland menage to resolve some rather gritty issues and allow Noah to bed down the woman of his choice. Or rather allow the woman to bed down the man of her choice. Be that as it may, the novel ends on an upbeat note, which is the least modern thing about this book.

What lifts On the Verge from yet another nihilistic statement of modern man's corruptibility and damnation is Eberhart's lyricism, his faith in mankind, and finally his homage to nature that unmistakable voice in American literature that began well before Samuel Sewall eulogized Plum Island in the waning decades of New England's 17th century. And it's this allegiance between Man and Nature that is Eberhart's strength in the novel his real strength.

Human passions wax and wane throughout the book. When Noah (like the title of the novel, he too is aptly named) tussles with either Jill or Lauren, the book verges on soap-opera blandness. But when he rids himself of the debilitating weight of these women and their demands when he can submerge his personality into the land then we feel in the presence of a writer with something pertinent to say, something worthwhile listening to.

Noah is building an ark in this novel a stone ark. Instead of packing it with God's creatures from the natural world, however, Eberhart chooses to people it with a batch of social castoffs. Noah survives. His dream survives. And the woman he chooses to share his dream survives. All in a manner of speaking. The survivors are on the verge of something better in life.

A frequent reviewer for this magazine,Professor Medlicott teaches English at theUniversity of Connecticut.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

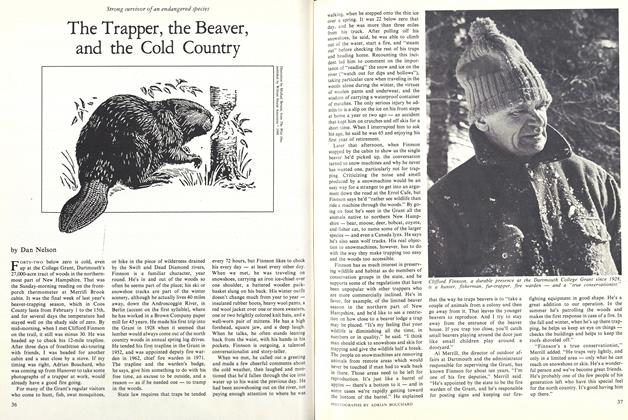

FeatureThe Trapper, the Beaver, and the Cold Country

March 1980 By Dan Nelson -

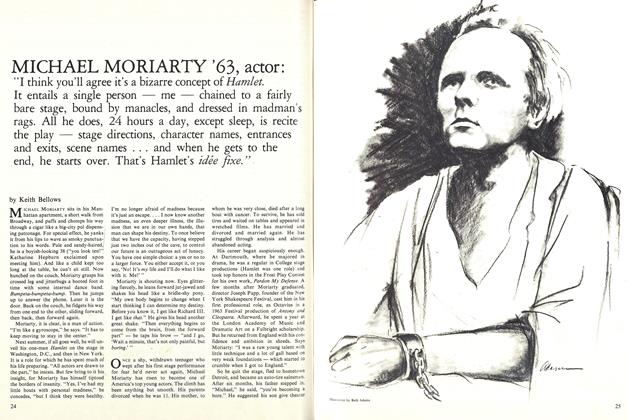

Cover Story

Cover StoryMICHAEL MORIARTY ’63, ACTOR

March 1980 By Keith Bellows -

Feature

FeatureManaging Dartmouth’s Money Slide Turns to Rally

March 1980 By Dero A. Saunders -

Article

ArticleTracker of the Right Stuff

March 1980 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1913

March 1980 By CARL C. FORSAITH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

March 1980 By JEFF IMMELT

Books

-

Books

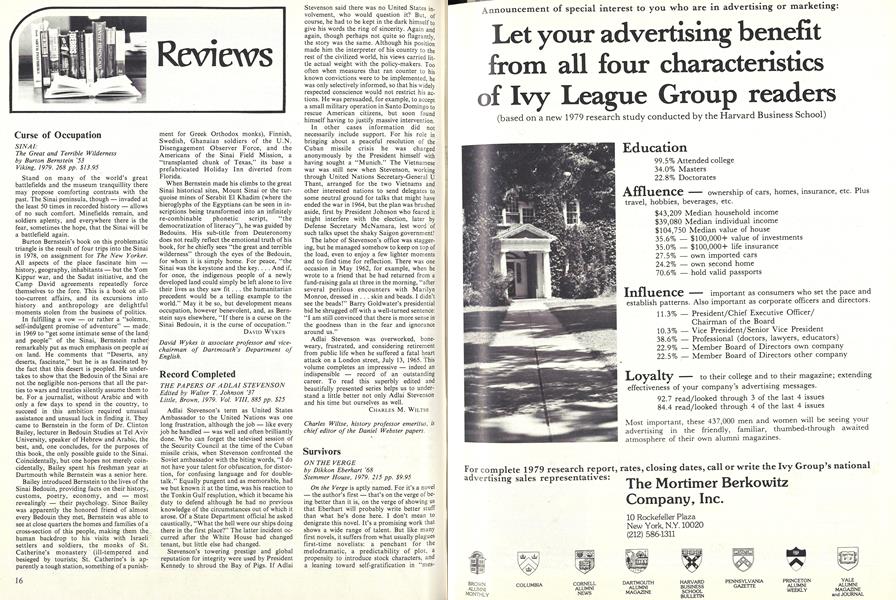

BooksAlumni Articles

APRIL 1966 -

Books

BooksEDITOR’S PICKS

MARCH | APRIL -

Books

BooksTHE TIME OF LAUGHTER, A SENTIMENTAL CHRONICLE OF THE TWENTIES – THE HUMOR AND THE HUMORISTS.

DECEMBER 1967 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Books

BooksMAN AND THE COMPUTER

JANUARY 1973 By J. MICHAEL TURNER '66TH -

Books

BooksAMERICAN MILITARY GOVERNMENT IN KOREA

October 1951 By John W. Masland -

Books

BooksLINEAR SYSTEMS IN COMMUNICATION AND CONTROL.

JUNE 1972 By THOMAS F. PIATKOWSKI