“I think you'll agree it's a bizarre concept of Hamlet. It entails a single person me chained to a fairly bare stage, bound by manacles, and dressed in madman's rags. All he does, 24 hours a day, except sleep, is recite the play stage directions, character names, entrances and exits, scene names... and when he gets to the end, he starts over. That's Hamlet's idee fixe."

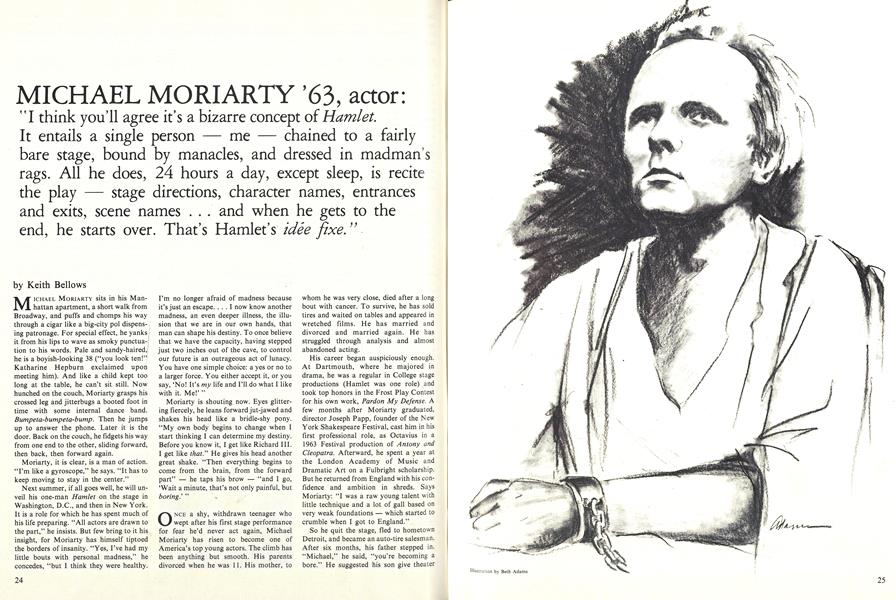

MICHAEL MORIARTY sits in his Manhattan apartment, a short walk from Broadway, and puffs and chomps his way through a cigar like a big-city pol dispensing patronage. For special effect, he yanks it from his lips to wave as smoky punctuation to his words. Pale and sandy-haired,I he is a boyish-looking 38 ("you look ten!" Katharine Hepburn exclaimed upon meeting him). And like a child kept too long at the table, he can't sit still. Now hunched on the couch, Moriarty grasps his crossed leg and jitterbugs a booted foot in time with some internal dance band. Bumpeta-bumpeta-bump. Then he jumps up to answer the phone. Later it is the door. Back on the couch, he fidgets his way from one end to the other, sliding forward, then back, then forward again.

Moriarty, it is clear, is a man of action. "I'm like a gyroscope," he says. "It has to keep moving to stay in the center."

Next summer, if all goes well, he will unveil his one-man Hamlet on the stage in Washington, D.C., and then in New York. It is a role for which he has spent much of his life preparing. "All actors are drawn to the part," he insists. But few bring to it his insight, for Moriarty has himself tiptoed the borders of insanity. "Yes, I've had my little bouts with personal madness," he concedes, "but I think they were healthy. I'm no longer afraid of madness because it's just an escape.... I now know another madness, an even deeper illness, the illusion that we are in our own hands, that man can shape his destiny. To once believe that we have the capacity, having stepped just two inches out of the cave, to control our future is an outrageous act of lunacy. You have one simple choice: a yes or no to a larger force. You either accept it, or you say, 'No! It's my life and I'll do what I like with it. Me!'"

Moriarty is shouting now. Eyes glittering fiercely, he leans forward jut-jawed and shakes his head like a bridle-shy pony. "My own body begins to change when I start thinking I can determine my destiny. Before you know it, I get like Richard III. I get like that." He gives his head another great shake. "Then everything begins to come from the brain, from the forward part" he taps his brow "and I go, 'Wait a minute, that's not only painful, but boring.'"

ONCE a shy, withdrawn teenager who wept after his first stage performance for fear he'd never act again, Michael Moriarty has risen to become one of America's top young actors. The climb has been anything but smooth. His parents divorced when he was 11. His mother, to whom he was very close, died after a long bout with cancer. To survive, he has sold tires and waited on tables and appeared in wretched films. He has married and divorced and married again. He has struggled through analysis and almost abandoned acting.

His career began auspiciously enough. At Dartmouth, where he majored in drama, he was a regular in College stage productions (Hamlet was one role) and took top honors in the Frost Play Contest for his own work, Pardon My Defense. A few months after Moriarty graduated, director Joseph Papp, founder of the New York Shakespeare Festival, cast him in his first professional role, as Octavius in a 1963 Festival production of Antony andCleopatra. Afterward, he spent a year at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art on a Fulbright scholarship. But he returned from England with his confidence and ambition in shreds. Says Moriarty: "I was a raw young talent with little technique and a lot of gall based on very weak foundations which started to crumble when I got to England." So he quit the stage, fled to hometown Detroit, and became an auto-tire salesman. After six months, his father stepped in. "Michael," he said, "you're becoming a bore." He suggested his son give theater another try. Moriarty agreed, successfully auditioning at the Tyrone Guthrie Theater, in Minneapolis, where he spent four years doing everything from The Master Builder to Mertcn of the Movies. At length, he returned East, scrounging work in Off-Broadway shows, regional theater, and forgettable movies Glory Boys (his first), Hickey and Boggs, and Shoot It. By now married to Francoise Martinet, a French-born dancer with the Joffrey Ballet they later divorced he eked out a living serving beer and burgers in a Manhattan saloon and playing piano in Greenwich Village nightspots.

"I must have thought I'd make it," he says, "or I would have given up. At one stage, I said, 'No, I'm through. I can't take it anymore. I'm going nowhere. I'm a nobody.' If it had been left to me, I'd probably be in the river." But with the support of friends and family he plugged away. "For a number of years, I felt like a barren tree. I knew there were a lot of creative juices at work inside me and yet nothing was happening. Then in 1973 I suddenly bore fruit. Boy, did I ever! It was hanging all over me."

That year he turned in an Emmywinning performance as the Gentleman Caller opposite Katharine Hepburn in Tennessee Williams' The Glass Menagerie. Next came a Tony award for his Broadway portrayal of Julian Weston, a despairing homosexual hustler in Find Your WayHome. And his performance as Henry Wiggen, the blue-eyed, fair-haired ballplayer who befriends a dying catcher (Robert DeNiro) in Bang the Drum Slowly earned him widespread popular acclaim. "The kid's been in some dogs till now," said his father after a screening, "but he sure is okay in this one."

Within 12 months, Moriarty had graduated to that corps of American character actors which includes DeNiro, Al Pacino, and Dustin Hoffman who rely on a potent blend of craft and technique and what Moriarty calls "interior work." Although wraithlike his own appraisal and lacking the overpowering presence of a Marlon Brando, Moriarty has undeniable star quality. He is a very physical actor even if his former wife did once disparage his dancing by saying he had "spoon feet" and he relies on finetuned attention to detail and an ever-expanding repertoire of nuance and gesture. "But Michael is also a very mental actor," observes Joseph Papp. Indeed, he draws as much upon intellect as instinct to bring life to his characters; he contends he may think too much and even in casual conversation picks apart ideas like a child dismantling an Oriental puzzle box. "Nothing is simple with Michael," says Papp. "There's madness in his method. He's so subtle he never tips his mitt. He relentlessly holds your attention. Arouses your curiosity. Keeps you intrigued as to how he will resolve an artistic situation. He always surprises."

Still, he often abandons his intellectual grip on a character, succumbing glassyeyed to something beyond technique. "Michael prepares intensely for a role so, as he says, he knows that he knows it so he can forget," says Ronald Hufham '59, a New York lawyer who has known Moriarty since college. "Then he tries to be a clean slate upon which a character is written." So one understands what Moriarty means when he says he had nothing to do with the best part of his career. "Take The Executioner's Song by Norman Mailer," he says earnestly. "I know it was written by a larger force than Mailer. He told my wife, 'When I wrote that, I think I got out of the way.' There's a lot to that: If you can get out of the way, it will pick you up and carry you along.

"You see, theater is a religious ritual, the closest thing to the genesis of performing that there is. If I had been raised in a rigid Catholic family" he wasn't, but did attend a Jesuit high school "I might have become a priest. I understand the clarity and meaning of ritual. On stage, you're up there dancing a song to God. If the audience can understand that, they in turn become part of the ritual.... The basic direction of great theater is straight up or straight down into your soul. Entertainment is horizontal. It just distracts."

SINCE his golden year of 1973, the roles and accolades have piled up. He made a brief appearance as a Marine brig officer in The Last Detail (with Jack Nicholson) and brought chilling malignancy to his portrayal of Richard III at Lincoln Center. On television, he played Dick Maple depicting him in early as well as middle adulthood in Too Far to Go, an adaptation of a John Updike short story. In Report to the Commissioner he was an idealistic rookie cop, a role he helped research by riding through darkened streets with a New York City vice squad. He was Wilbur Wright in The Winds of theKitty Hawk and, in The Deadliest Season, a marginal hockey player who, forced to play tough, gives a rival player such a battering he later dies. And as Nazi Erik Dorf in Holocaust a role he says "helped make me a Catholic" his Emmy-winning performance was so effective that a women later recognized him in a Miami coffee shop and screeched: "Oh, you're the one. I hate you, I hate you! God, do I hate you!"

Moriarty has made an uneasy alliance with success, which he once called a form of death, for it gives him the freedom to be daring. He is a great innovator as great in the theater, one friend says, as George Balanchine is in dance. "He will leave his imprint on any company he works for," says Joseph Papp. He is simply not interested in the status quo his experimental Hamlet is proof of that and constantly looks for new ways to view old forms. Ted Kennedy fascinates him as the subject of tragic comedy ("his story has all the makings of a great dilemma"), and brother Jack offers even greater possibilities.

"I'd like to do Shakespeare's Henry V set in the Kennedy Administration," He smiles impishly. "There are no playwrights today who write to the size of Shakespeare. We're a nation that can't afford to get petty. But if our writers think of us as petty, we'll be petty. The only way we can relate to what Henry V means and meant to the English is by what John F. Kennedy means to the present generation. He was the flowering of King Arthur, the charming king of romance, Peck's bad boy suddenly given the throne and turning into one of the world's greatest leaders. He put our hearts back in our chests and gave us a style and a courage and a zest and a flair. A real sense of joy and hero.

"Henry would work well with Boston rhythms.... In one scene the Dauphin of France sends him a box of tennis balls saying, in effect, 'That's all you're worth, Henry' and the whole rhythm of the speech...." Moriarty looks upward and shifts easily into a drawn-vowel, sing-song Boston cadence. "'His present and your pains we thank you for: When we have match'd our rackets to these balls, we will in France, by God's grace, play a set shall strike his father's crown into the hazard.'" Moriarty grins broadly. "It makes perfect sense. Even the once-more-into-the-breech speech. It's like the Cuban missile crisis. You could do it multimedia. Look right into the camera, with the presidential seal in back, and say, 'We must imitate the action of the tiger, stiffen the sinews, summon up the blood....'"

Moriarty has always searched for roles that challenge his abilities ("the most important ones are usually the most difficult"). And he is a gambler. "He's not afraid to take a chance," says Ronald Hufham. "He's so free in performance. He's not scared of emotion. He's not scared of anything."

Sometimes he gets burned. In the 1978 film, Who'll Stop the Rain, a loose adaptation of Robert Stone's Dog Soldiers, Moriarty gambled on the part of Converse, a renegade Vietnam veteran who involves his wife and best friend in a drugsmuggling scheme. It is a film Moriarty hates. He agreed to the role, he says, because he thought he could illuminate a story that was basically a made-for-market pastiche of sex and violence and drugs. "I thought I could pull something out of the fire. I lost." Moriarty sighs and shakes his head. "The movie was a phony, a fashionable idea of America. The effects of drugs on Tuesday [Weld] were dreamy, languorous. But look at somebody on heroin. They suddenly lose all tone in their face and body. There's no romance to that. No dreamy eyes. It is death. I had a little snorting scene, and I went right for what I saw. To the truth. The pain. The ugliness. They said, 'Uggh! We can't show this.' Well, that's just dishonest."

Moriarty hasn't done a film since Rain. He hasn't done any major production since his critically acclaimed performance last summer as Micah in Broadway's shortlived G. R. Point, a play about American soldiers in Vietnam. And he is getting itchy. But the scripts being offered are terrible. "I just read one recently, though, that's so bad, I think it's great. It's an eighties version of Repulsion. If Polanski directed it, it would be a piece of genius. It's about evil, but it's also about love. I sat on the edge of my couch reading it, and it got so outrageous I got sick to my stomach. I threw it in the waste basket. But it kept hanging in my head. I know what it needs. It's well written and there's intelligence there and it went al-1-1-1 the way without stopping. It's a nightmare film: You get to a point where you see images of the devil not like in The Exorcist but as a psychotic might see them. The role is so courageous, it warrants being done. People will embrace it or spit on it. They'll be outrage a

That's typical Moriarty. Constantly probing for reaction. Stirring outrage. He seems to relish traumatizing audiences, stunning them with visions of pain or death or unpleasant reality. He has repeatedly gone to the shadows of life on stage and screen, often playing victims of war, violence, emotional assault. "Why do I explore evil?" Moriarty gazes into space for a few moments, lost in thought, then returns. "It's where you need love most. Heaven comes to hell to alleviate the pain. Playwrights and novelists go to the hell of our nature. Antibodies to a disease don't run to the healthy part of the body and do a light comedy. They run to the fevered part. That's why Tennessee Williams writes all those bizarre dark plays."

Williams is Moriarty's favorite playwright, preferred to Eugene O'Neill, he says, because Williams has a comic vision of life and O'Neill a tragic one. "O'Neill gives up in defeat and says evil does overwhelm us; but Williams says, 'No, evil is a road to heaven.' You can't go to heaven around hell. An artist can't skirt the darkness." He taps his cigar in the ashtray, then puts the cigar back in his mouth, draws hard and exhales a great billow of bluish smoke. "One of the oreatest performances and the greatest definition of evil I've ever seen was in a bad movie. Brando in Missouri Breaks. I'd kill for a performance like that. He took a trivial little Western and did a Shakespearean concept of death as a chameleon that changes faces and colors. And behind it, way, way back behind his eyes, there's a smile, like the laugh of Zarathustra, which shows such extraordinary understanding." He cocks his head, gives almost a leer and brings hand to ear as if listening for an echo. "Yet with all the darkness in my work, I have a total optimism about the world. Evil hasn't got a chance. It eats itself, and what is left is clean and good. The depth to which I explore it should be an example of courage to others: What have you got to be afraid of?"

Moriarty is repeatedly portrayed in print as a cheerless sobersides. The image is faulty. "I used to be melancholy," he concedes. "I had nervous breakdowns all the time." He tells a story he heard from Leonard Bernstein about Aaron Copland, who during the two composers' 45 years of friendship only once showed anger or tears. "Had he not put his pent-up feelings into his art you hear incredible flashes of rage in his music it's a good bet that Copland would have been psychotic and lashed out physically at the world," he says. What isn't said is that deprived of acting as catharsis Moriarty might be permanently at war with the world. "Success has made me more ebullient. I have a much better sense of humor. Not one of your vaster senses of humor, but it's growing, thank God. Which is a sign of health."

Moriarty admits to moodiness, but, say friends, when relaxed he is full of joy, full of laughter. "When he reaches an impasse in life or art," says one, "he breeches it with humor." He is often happiest when singing or playing the piano, and dominant in his living room is a baby grand. "The music goes back to his earliest childhood," says Ronald Hufham. "Even before his acting." An accomplished singer, song writer, and self-taught jazz pianist, he is collaborating with writer Mark Alan Za goren on White Jazz, a musical based on Moriarty's own life. As in his scuffling days, he still performs in local clubs, though no longer as a soloist (he says he used to "hide" behind the piano). For a show last summer he added two back-up musicians on bass and piano and turned to stand-up delivery, giving his songs an unorthodox, jazzy treatment.

BUT then unorthodoxy is a Moriarty trademark. So is risk-taking. On November 13, 1977, he embarked upon the riskiest venture of his career. Inspired by the Stratford (Ontario) Shakespeare Festival, Moriarty recruited the legal help of Ronald Hufham and launched Potter's. Field, a New York-based theater company devoted to producing the major plays of the world's great playwrights, principally Shakespeare. He wants it to have "the range and depth of a symphony orchestra," and laments that "in this theater-city-of- theater-cities" there is not one major acting ensemble. London and Paris have two; and New York has major companies in ballet (five), opera (two), and symphony (one). "Why not a major theater company?" he asks. "This country still perceives theater as popular entertainment. It's not. It's an art form that demands endowment like ballet and opera."

Moriarty insists that Potter's Field, which has a seven-member board of trustees, be funded fully by endowment because he believes it should survive only through community support. "I don't want to keep something alive if no one wants it," he says. Hence, he refuses to sink into it large personal sums, though he has pledged $28,000 over four years the equivalent, he says, of a college education ("I may be getting off lightly by Dartmouth standards"). He also gives of his time, sometimes spending up to eight hours daily tangling with the administrative and fundraising demands of Potter's Field "a worse nightmare than I could have imagined." But the artistic benefits are considerable.

In the tradition of major dance companies, Potter's Field is also a school (it has graduated some 275 students). And as its manager and artistic director, Moriarty has been able to exercise his great skills as a teacher. "Michael's a born teacher," says Hufham, now the company's executive director. "He zeros in with an unerring eye on mistakes. But he's not destructive like some teachers. He nurtures."

Usually giving 20- to 30-minute classes twice weekly, Moriarty begins with an informal discussion of craft. Then he might move on to breathing technique, putting his students through various exercises. Or, as he has done, read a soliloquy from Hamlet, first in the British style, then the American

he contends the British are "acting machines" driven by directors at a heartless ten-line-per-breath pace while Americans are less restricted. "The teaching sharpens my own acting tools," he says, "so I get better and stronger in the process." He is disenchanted with American teaching especially in the colleges and grumbles that its goal is often to cram. "Stuff the brain. Get it really rich. And when the goose dies, all that's left is pate. Which is just an appetizer, not the main course. By its meaning educare education is to lead out, not stuff."

Housed in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, on New York's Upper West Side, Potter's Field has struggled from its infancy. Its overhead is staggering, and Moriarty is discouraged and bitter about its critical reception, especially from the New York Times. "It's the Supreme Court, and there's no Court of Appeals," he says in disgust. "It can pocket-veto any piece of New York theater it wants and cause a lot of problems for you." The Times did just that with the company's first production, Love's Labour's Lost, which Moriarty directed and which he concedes met with an almost unanimously chilly reception. There have since been brighter moments. Moriarty and the company were featured on the premiere of WNET-TV's Skyline, and Potter's Field recently brought forth Left Field, a developmental workshop that debuted with The Mischiefs You Foresee, a theatrical potpourri of scenes from 11 Shakespeare plays.

Yet Moriarty is fearful for his company's future. "It's a long shot," he says simply. And though the New York media have broken countless companies with their indifference and critical assault, Moriarty won't relocate Potter's Field. "I refuse to treat New York like some catastrophic disease center which it has proven to be. It's filled with negativity and anger and resentment, and its very harsh to new ideas. I'll continue as long as I have joy in it. But I almost gave it up there a few weeks ago, and I may do it still. There's nothing in my life that I'll hang on to when it erodes my courage, which is grace under pressure."

"I've been murdered in this business. I've been loved and kissed and battered and bruised. I can take defeat. But I'm responsible for the needs and feelings of 75 people. That's frightening. A lot of them stand up there dazed and shaken. Still, the experience is helping me be a better human being. I used to think acting was everything. It's not. Being a better person is more important. Success isn't the Nobel Prize. It's responsibility. It's caring. I was once asked what I wanted on my gravestone. Only one line: "Here lies a man who knew the meaning of love."

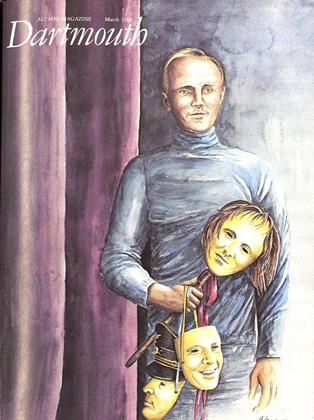

Moriarty makes up for a student production at Hopkins Center in the early sixties.

In Bang the Drum Slowly (above), Moriarty actually looked and moved like aballplayer, a feat seldom achieved in Hollywood. By the time of his portrayal ofRichard III at Lincoln Center, the fixed, other-world gaze was an M.M. trademark.

In Bang the Drum Slowly (above), Moriarty actually looked and moved like aballplayer, a feat seldom achieved in Hollywood. By the time of his portrayal ofRichard III at Lincoln Center, the fixed, other-world gaze was an M.M. trademark.

Staring evil in the face, as SS Officer Erik Dorf in Holocaust. "Evil hasn't gota chance," Moriarty says now. "It eats itself, and what is left is clean and good."

Keith Bellows '74 wrote "Ups and Downsin the Big Leagues," about professionalathletes Jim Beattie and Reggie Williams,in the September 1979 issue. He combinesfree-lance writing and editing Hockey magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Trapper, the Beaver, and the Cold Country

March 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureManaging Dartmouth’s Money Slide Turns to Rally

March 1980 By Dero A. Saunders -

Article

ArticleTracker of the Right Stuff

March 1980 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1913

March 1980 By CARL C. FORSAITH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

March 1980 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

ArticleThat Man in Our Living Room

March 1980 By M.B.R.

Keith Bellows

Features

-

Feature

FeatureDays of Pomp & Circumstance

July/Aug 2013 -

Feature

FeatureRudolph Ruzicka's Two Dartmouth Medals

OCTOBER, 1908 By Edward Connery Lathem -

Feature

FeatureTHE IVORY FOXHOLE

October 1976 By JEFFREY HART -

Feature

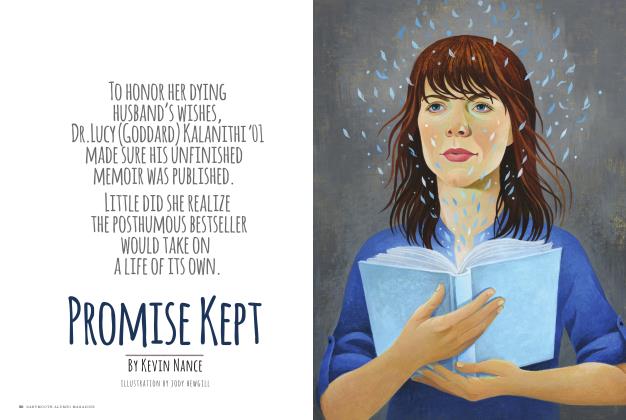

FeaturePromise Kept

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 By KEVIN NANCE -

Feature

FeatureWomen at the Top (almost)

May 1977 By SHELBY GRANTHAM