Strong survivor of an endangered species

FORTY-TWO below zero is cold, even up at the College Grant, Dartmouth's 27,000-acre tract of woods in the northernmost part of New Hampshire. That was the Sunday-morning reading on the frontporch thermometer at Merrill Brook cabin. It was the final week of last year's beaver-trapping season, which in Coos County lasts from February 1 to the 15th, and for several days the temperature had stayed well on the shady side of zero. By mid-morning, when I met Clifford Finnson on the trail, it still was minus 30. He was headed up to check his 12-mile trapline. After three days of frostbitten ski-touring with friends, I was headed for another cabin and a seat close by a stove. If my timing was right, Adrian Bouchard, who was coming up from Hanover to take some photographs of a trapper at work, would already have a good fire going.

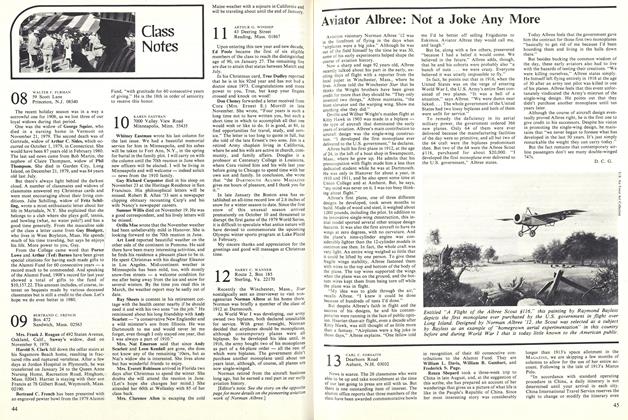

For many of the Grant's regular visitors who come to hunt, fish, swat mosquitoes, or hike in the piece of wilderness drained by the Swift and Dead Diamond rivers, Finnson is a familiar character, year round. He's in and out of the woods so often he seems part of the place; his ski or snowshoe tracks are part of the winter scenery, although he actually lives 40 miles away, down the Androscoggin River, in Berlin (accent on the first syllable), where he has worked in a Brown Company paper mill for 45 years. He made his first trip into the Grant in 1928 when it seemed that lumber would always come out of the north country woods in annual spring log drives. He tended his first trapline in the Grant in 1952, and was appointed deputy fire warden in 1962, chief fire warden in 1971. The trapline and the warden's badge, he says, give him something to do with his free time, an excuse to be outside, and a reason as if he needed one to tramp in the woods.

State law requires that traps be tended every 72 hours, but Finnson likes to check his every day - at least every other day. When we met, he was traveling on snowshoes, carrying an iron ice-chisel over one shoulder, a battered wooden pack- basket slung on his back. His winter outfit doesn't change much from year to year- insulated rubber boots, heavy wool pants, a red wool jacket over one or more sweaters, one or two brightly colored knit hats, and a well-worn pair of mittens. He has a high forehead, square jaw, and a deep laugh. When he talks, he often stands leaning back from the waist, with his hands in his pockets. Finnson is outgoing, a talented conversationalist and story-teller.

When we met, he called out a greeting and made a few cheerful comments about the cold weather, then laughed and mentioned that he'd fallen through the ice into water up to his waist the previous day. He had been snowshoeing out on the river, not paying enough attention to where he was walking, when he stepped onto the thin ice over a spring. It was 22 below zero that day, and he was more than three miles from his truck. After pulling off his snowshoes, he said, he was able to climb out of the water, start a fire, and "steam out" before checking the rest of his traps and heading home. Recounting this incident led him to comment on the importance of "reading" the snow and ice on the river ("watch out for dips and hollows"), taking particular care when traveling in the woods alone during the winter, the virtues of woolen pants and underwear, and the wisdom of carrying a waterproof container of matches. The only serious injury he admits to is a slip on the ice on his front steps at home a year or two ago - an accident that kept him on crutches and off skis for a short time. When I interrupted him to ask his age, he said he was 65 and enjoying his first year of retirement.

Later that afternoon, when Finnson stopped by the cabin to show us the single beaver he'd picked up, the conversation turned to snow machines and why he never has wanted one, particularly not for trapping. Criticizing the noise and smell produced by a-snowmachine would be an easy way for a stranger to get into an argument down the road at the Errol Cafe, but Finnson says he'd "rather see wildlife than ride a machine through the woods." By go ing on foot he's seen in the Grant all the animals native to northern New Hampshire - bear, moose, deer, bobcat, coyote, and fisher cat, to name some of the larger species - and even a Canada lynx. He says he's also seen wolf tracks. His real objection to snowmachines, however, has to do with the way they make trapping too easy and the woods too accessible.

Finnson has as much interest in preserving wildlife and habitat as do members of conservation groups in the state, and he supports some of the regulations that have been unpopular with other trappers who are more commercially inclined. He's in favor, for example, of the limited beaver season in the northern part of New Hampshire, and he'd like to see a restriction on how close to a beaver lodge a trap may be placed. "It's my feeling that your wildlife is diminishing all the time, in numbers or in quality," he said. "I think man should stick to snowshoes and skis for trapping and give the wildlife half a break. The people on snowmachines are removing animals from remote areas which would never be touched if man had to walk back in there. Those areas need to be left for reproduction. It's just like a barrel of apples - there's a bottom to it - and in some cases we're rapidly getting toward the bottom of the barrel." He explained that the way he traps beavers is to "take a couple of animals from a colony and then go away from it. That leaves the younger beavers to reproduce. And I try to stay away from the entrance of the beaver house. If you trap too close, you'll catch small beavers playing around the door just like small children play around a dooryard."

Al Merrill, the director of outdoor affairs at Dartmouth and the administrator responsible for supervising the Grant, has known Finnson for about ten years. "I'm one of his fire deputies," Merrill said. "He's appointed by the state to be the fire warden of the Grant, and he's responsible for posting signs and keeping our firefighting equipment in good shape. He's a great addition to our operation. In the summer he's patrolling the woods and makes the first response in case of a fire. In the fall and winter, when he's up there trapping, he helps us keep an eye on things - checks the buildings and helps to keep the roofs shoveled off."

"Finnson's a true conservationist," Merrill added. "He traps very lightly, and only in a limited area - only what he can reach on snowshoes or skis. He's a wonderful person and we've become great friends. He's probably one of the few people of his generation left who have this special feel for the north country. It's good having him up there."

EARLY the next morning Finnson came by the cabin and invited us to go out and check traps with him. We sat for an hour or two inside - where the temperature was 80 - trading stories, drinking coffee, eating our way through a box of doughnuts Finnson supplied, and

waiting for the outside temperature to warm up to minus 20. "The coldest I've ever been up here," Finnson recollected, "was one day when it was 35 below zero with a 70-mile-an-hour wind blowing. It was blowing chickadees right out of the trees and onto the river and rolling them in the snow. I'd pick them up and they'd die there in my hands." He told us about the time his friend Sam Brungot, custodian of the Grant from 1951 to 1961, was given a couple of lobsters by a visitor. To keep them cool until dinner time, Sam hung them in the river by a line tied to the Dead Diamond bridge. Later that afternoon, when the game warden happened to stop by Sam's cabin, Sam asked if it was legal to take lobster out of the river. When the puzzled warden replied he didn't know of any law prohibiting it, Sam brought him down to the bridge to check the trap, displayed the lobsters, and invited the warden to supper.

Adrian Bouchard and Finnson grew up together in Berlin, and before Bouchard

came to Hanover (where he eventually became the College photographer), he worked on a logging crew in the Grant. Finnson worked in the mills and spent much of his time in the Grant hunting and fishing. Besides knowing the country, both men know its human history, and both can recount the exploits of many of the characters who worked in the woods before the logging industry was mechanized. They talked about famous fighters, deer-jackers, tough foremen, and a logging-camp hunter so quiet in the woods he was called The Ghost. They described a friend who was so proficient with a rifle that he could sit on his porch in town, aim at a church steeple, and ring the bell with every shot.

Later that morning, as we snowshoed out along the Swift Diamond, I asked Finnson how he started trapping. "My father was never a trapper," he said, "but when I was a kid I was always trying to catch something. I started by catching red squirrels and I worked my way up the line. You learn by your mistakes. Books help, and so do other trappers, but you have to get out and do it. I've trapped mink, otter, muskrat, bobcat, fisher cat, and beaver."

"Otter is the hardest to catch," he pointed out. "They'll travel as much as 20 miles in one night. The way I catch them is in blind sets on their runs. When they're coming up a river and there is a point of land sticking out, they'll always go over that point on the same trail. I drop a tree across the run - well away from the rise and fall of the water - and get them used to going over it. They break their stride to go over the tree, and I set a number 14 trap on each side of it. Until the trapping law changed a couple of years ago, I used to trap otter in the fall. You can trap them in the winter now, but they've gone by."

Finnson, the only trapper with permission to operate in the Grant, has trapped mostly beaver in recent years, although this fall he did well with fisher. The beavers he takes weigh about 50 pounds, larger than average. Animals this size have a pelt with a combined length and width of about 65 inches, classified as a "blanket." Because the furs taken in the northern part of the state are generally of better quality than those taken in the south, Finnson could sell his blanket-size pelts for about $25 to $30 each last year. He occasionally took a super-blanket, with a combined length and width of more than 70 inches, and sold it for about $35. The largest pelt he's ever taken measured 80 inches. At one time, when the market was at its peak, trappers were paid a dollar an inch for prime beaver furs, but lately the market has been poor. "The market depends on styles and the de mand for beaver coats and hats," Finnson said. "I wanted my wife to have a beaver coat, but she said she wouldn't care for it." Because he takes 12 to 15 beavers each season - a fraction of what the Grant supports- Finnson makes just about enough money to cover his expenses - primarily the cost of driving his four-wheel-drive truck up from Berlin. He maintains it would be almost impossible to make a living by trapping in the Northeast, and says that if he were trapping for the money he "would have quit long ago."

THERE are about 800 licensed trappers in New Hampshire. According to furbearer harvest records kept by the state fish and game department, 4,082 beavers were taken during the 1978-79 season, and the average price paid per pelt was $22.55. During that same season, the total dollar value of pelts taken from the 11 fur-bearing species which can be legally trapped and sold was almost $370,000. The number of iicensed trappers fluctuates from year to year, depending in part on the prices different furs are bringing. The average price paid for beaver, for example, since the first open season in 1940, has ranged from almost $49 in 1946, when there were over 1,400 licensed trappers, to less than $10 in 1961, when 532 licenses were given out. Since 1970, the average price for beaver has stayed between $l4 and $23.50. Fisher cat, in contrast, brought almost $100 each in 1976, while the average weasel pelt was worth only 770 that year. This year the price of beaver is up, and Finnson is getting about $60 for each fur.

Trapping, like hunting, is an issue that exercises people's emotions, and there doesn't seem to be much that defenders and opponents of the activity agree about. Those on one side argue for preserving a "threatened heritage," while those opposed speak out against cruelty to animals. The anti-trappers claim that trapping is a barbarous anachronism; the trappers deny that the animals they take experience much suffering, and maintain that furbearing species are a renewable resource. Finnson is no friend of Cleveland Amory, but he would agree with those who would restrict trapping that there ought to be limits, based on information about the health of the species, on when and how animals may be taken. There would, however, be considerable disagreement about specific recommendations, and no agreement about the overall objectives of a group such as the Advocates of Controlled Trapping (ACT), a Hanover-based political-action organization which would ultimately like to eliminate commercial or recreational trapping altogether. "It is our belief that the destruction of this native wildlife for only the monetary profit and vanity of a few is cruel, wasteful, and unnecessary," ACT said in a petition supporting legislation to outlaw commercial land-set trapping. Even in predominantly rural New Hampshire, bills designed to cut back on trapping have been gaining votes each time they are introduced in the legislature.

Finnson claims that "these kind of people are anti-everything. They show pictures about how cruel the steel trap is. They're getting so that they're even against hunting. Why, we have met people here in the north who are even against fishing. What they're trying to do, of course, is stop everything. We know it's a bunch of malarkey, but a lot of people who don't know what the actualities of wildlife are believe this sort of thing."

I asked if he didn't think a steel trap was painful to the animal caught in it. Finnson said, "No, I don't think the traps are particularly painful to the animals - not if they're set and tended properly. I can put a trap on my finger and sit around watching TV all evening. These people who talk about how cruel a trapper is ought to spend half a day in a slaughter house and see how the animals they eat are handled."

The beaver population in New Hampshire is expanding rapidly, and the species has made a remarkable comeback since trapping virtually wiped it out in the late 1800s. The animals returned to the northern part of the state in about 1912, and over the next couple of decades were reintroduced by the fish and game department to other areas. By the early 19605, according to the department's wildlife biologists, the entire state was populated to its carrying capacity, and lately the booming population has become a problem. In recent years the department's policy has been to encourage the species in areas where its presence is believed to be worthwhile, but to remove nuisance colonies.

By building dams the beaver provides valuable habitat for wildlife, and the ponds created preserve water in dry spells. Problems occur when the animals plug culverts, build dams against bridges, and flood roads, timberland, fields, and lawns. A friend who lives near Hanover has a healthy colony actively at work in his back yard. The law enforcement division of the fish and game department has been given the responsibility of controlling the nuisance colonies by draining ponds, dynamiting dams, or commissioning private trappers to relocate the animals when landowners complain of their presence. In southern New Hampshire, where the population is growing the fastest, fish and game personnel complain that they are spending much of their time as beaver control agents. The cost of dynamite (the most efficient tool for removing dams), the cost of gasoline needed to comply with federal regulations requiring the use of two separate vehicles to transport explosives, and the amount of time required to do the work have become problems for the agency. The department gears the beaver trapping season, in part, to the harvest of surplus animals, and there is some resentment when its personnel are requested to remove a dam by a landowner who has denied commercial trappers permission to take beaver during the regular season.

FINNSON follows the common practice of setting his beaver traps underwater, ; and he uses medium-size leg-hold traps that sell for about $10 each - although some trappers use Conibear traps, larger : and more expensive devices designed to kill an animal instantly by snapping shut on its neck or back. In the case of a leg-hold trap set underwater, the beaver dies by drowning.

As we approached his first trap, Finnson said he doubted if we'd find any beavers because the cold weather would discourage them from leaving their comparatively warm houses. Earlier that week, on a cold, still day, I had seen a column of steam rising straight up out of a beaver lodge built in a shallow pond. The beavers Finnson traps on the Diamond rivers, however, build their shelters by burrowing into the bank because a structure built in the water wouldn't survive the spring torrent. Finnson sets his traps in the river, a distance away from the entrance to the lodge, and when we walked out onto the river it was easy to locate the trap by a pole sticking out of the ice. Finnson doesn't like to make his traps too obvious, however, because he has had both traps and animals stolen from areas outside the Grant. On occasion he has had up to 40 mink sets and as many as 70 muskrat traps to check, all the traps more or less hidden. "You just remember where you put them," he said. "If you mark the location for yourself, you also mark it for other people."

He took off his packbasket, which usually contains an ax, a scoop for dipping slush out of the hole he chops in the ice, a trap or two, nails for constructing a stand for the trap and bait, a knife, wire, and a pair of pliers. Several inches of ice had formed in the hole he had chipped out the previous day, so he set to work making another opening over the trap. Sometimes he uses an ice chisel, sometimes the ax, but enlarging a hole with an ax is wet work. He had neglected to bring his scoop, so he removed his mittens and dipped the slush out of the hole with his hands, occasionally stopping to warm them under his arms. The temperature was still well below zero and the wind was blowing. Once the hole was clear he peered down into the water. No beaver. The season was almost over, so he decided to dismantle the set. After chipping away more ice he eventually pulled up the unsprung trap, his hands in and out of the water, pulling wire loose from the ice, removing the trap from the stand. The procedure was repeated at several locations.

The trap is attached by wire to a platform built near the base of a sturdy pole anchored in the riverbed. The bait, a stick of green aspen - "popple" - is nailed to the pole several inches above the trap. Depending on from which side of the pole the bait protrudes, Finnson knows which foot the beaver will place in the trap. "If you have a piece of popple sticking out on the left side of the pole," he explained, "you can guarantee you'll catch the beaver on his right front foot. When he swims up to the set to take the bait, he reaches up with his left front foot to grab hold of the stick, and then he reaches up with his mouth to cut it off the pole, but while he's doing that, he's putting his right front foot down, right on the trap."

As Finnson anticipated, he had no beavers in any of his traps. If he had taken one, however, he would have skinned it right on the river, leaving the carcass behind and bringing home only the pelt, which he would clean, stretch, and dry in his cellar. It takes him about 25 minutes to clean the fur and stretch it out on a frame, although he admitted it took several years of practice before he could complete the job in less than two hours. After the close of the season, when he has the furs all prepared, he brings them to the same buyer he has done business with for years. "I never got to like the taste of beaver meat," he said. "A lot of people do take it home and cook it, but after skinning a beaver I'm not too interested."

Just outside the Grant, I once met some trappers who were pulling a large sled full of beavers behind a snowmobile. At first, all I could make out was what looked like a pair of human feet hanging over the back end of the sled. The feet turned out later to be beaver tails, but at first glimpse they made me think of the local game warden who had been shot - on purpose, according to some accounts - by a disgruntled hunter. The trappers were cordial, however, and gave me and a friend two tails and a couple of haunches, which we pan-broiled for dinner that night. The tails, full of fat, are supposed to be a delicacy, but the haunches tasted better.

"Once you set a trap you're long gone," Finnson said with a laugh when we returned to the cabin. "Even in the summer, when I'm up here fishing, I'm looking for fur sign. Trapping's hard work, and it's usually cold, but it's fun. I like what I'm doing when I'm up here. I like the outdoors. It's peaceful and quiet. The good Lord made this fine land of ours, and I love being able to enjoy it. You know, a lot of trappers feel very perturbed if they don't catch something, but going home emptyhanded doesn't bother me a bit. I've had as many as 50 or 60 sets out. Some days I'd look at all those traps and not have a thing. If you have a heck of a long line you'll say to yourself, 'I didn't catch anything here, but perhaps in the next place. . . . ' That keeps you going. It leads you on. Each winter, the first time I set a bunch of traps, I can't sleep that night. I'm thinking about what I'm going to have the next day."

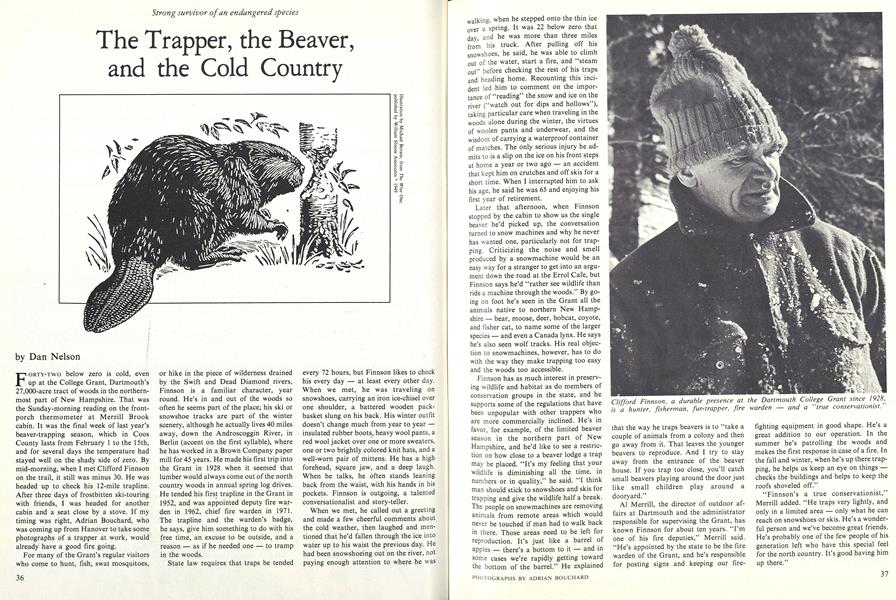

Clifford Finnson, a durable presence at the Dartmouth College Grant since is a hunter, fisherman, fur-trapper, fire warden and a "true conservationist."

Trapping can be cold, wet work. Finnson likes to check his beaver sets daily.

Miles of walking and hours of work go into taking a fur and preparing it for sale.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

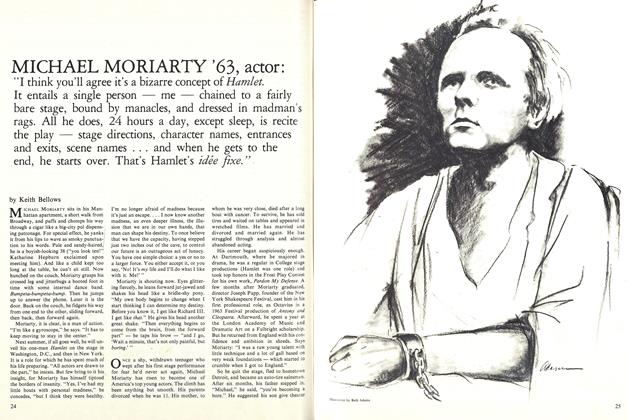

Cover StoryMICHAEL MORIARTY ’63, ACTOR

March 1980 By Keith Bellows -

Feature

FeatureManaging Dartmouth’s Money Slide Turns to Rally

March 1980 By Dero A. Saunders -

Article

ArticleTracker of the Right Stuff

March 1980 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1913

March 1980 By CARL C. FORSAITH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

March 1980 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

ArticleThat Man in Our Living Room

March 1980 By M.B.R.

Dan Nelson

-

Feature

FeatureShhh. There still are idealists abroad and they're called the Peace Corps

JUNE 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Article

ArticleA Journey: Five days to Big Rapids

September 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

Feature'A hell of a lot of life gone by'

November 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

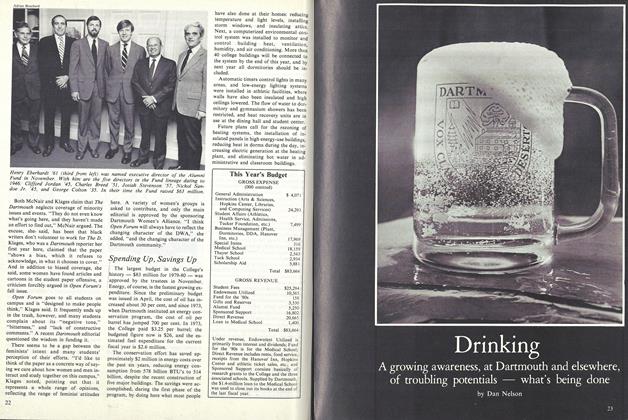

FeatureDrinking

JAN./FEB. 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureHAIR

November 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureConjuring Ethics in the Curriculum at Dartmouth

March 1981 By Dan Nelson

Features

-

Feature

FeatureLandauer Heads Alumni Council

JULY 1964 -

Feature

FeatureFreshman-Sophomore Curriculum Revised

FEBRUARY 1965 -

Cover Story

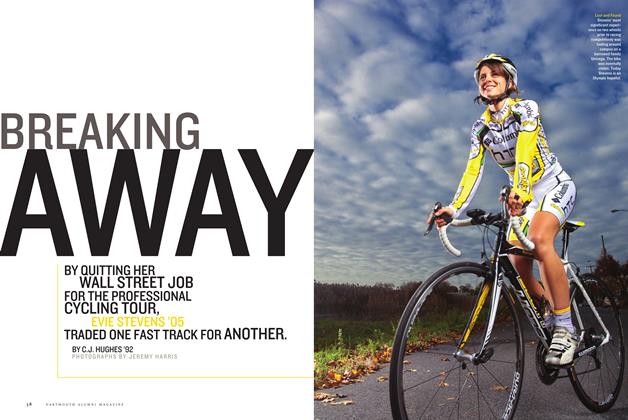

Cover StoryBreaking Away

Jan/Feb 2011 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

FeatureOPTIONS & ALTERNATIVES

March 1976 By D.N. -

Feature

FeatureThe Woman Who Was Not All There

June 1992 By Paula Sharp '79 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Mar/Apr 2006 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74