CONTRARY to persistent rumor and a certain amount of empirical evidence, Nancy Elliott, since 1963 director of the Alumni Records Office, has at no time been affiliated with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Her tracking record, however, rivals theirs: few alumni evade her net.

She did, to be sure, bring a wealth of useful experience to the job. A former CIA employee, she managed as one of her first acts of kindness in Hanover to open a safe for a local alumnus who had lost the combination. "It was just dumb luck," she confesses, "but don't print that." From Brooks Brothers in Boston ("I've always liked boys," she points out, "and clothes"), where she was office manager, she brought a gift for running a tight, efficient, yet neighborly ship.

When Charlotte Ford Morrison, alumni recorder for 36 years and for all intents and purposes founder of the office, was contemplating retirement in 1961, she wrote President Dickey about "a recurrent nightmare that my successor will be an IBM machine." She needn't have worried. IBM machines never look after students' plants when they're away on vacation or foreign study, find homes for neglected puppies, ski at Waterville Valley, correspond on an almost weekly basis with a special group of alumni, or get adopted by the class of 1943. And they hardly ever grumble.

Elliott grumbles a lot. She grumbles about elusive alumni, recalcitrant computers, crusading feminists, her dreary temporary quarters atop the Medical School, building plans that exclude greenhouses, anyone who is unkind to dogs, and writers who insist on attributing some credit for ARO's magnificent reputation to her rather than exclusively to her staff and her predecessors.

It is Elliott's responsibility to keep tabs on all alumni, of the associated schools as well as the undergraduate college "about 39,000 of my favorite kind of people men and now a few of the other kind." ("Ever since we got the computer," she grumbles, "it's impossible to be exact. When every living alumnus was on a three- by-five card, someone used to count those cards two or three times a year. Then we knew.")

Another of her tasks is to oversee the College's bulk mailings all the voluminous communication with alumni and some with undergraduates from across-the-board mass broadsides to regional club notices to class newsletters, the last of which she edits as well. Last year Elliott and her staff of a round dozen processed 1,989,024 pieces of mail and 15,475 changes of address for a peripatetic constituency.

Of the close to 40,000 living alumni, only 1,327 are currently listed as "not interested" and only 316 as "lost." The number whose unforwardable mail is returned varies from month to month and day to day, climbing noticeably after general mailings. The secret of the miniscule number in the "lost" column, says Elliott, is fast action on mail-return. As soon as the post-office form is received, ARO goes into high gear. Staff members, coming in early in the morning when phone lines are uncluttered, call first the last known home listing and then recent business numbers. That failing, inquiries go out to classmates, friends, and particularly in the case of young alumni, who move most frequently to families. "If you don't find them quickly," Elliott explains, "they're likely to be lost for good."

Her counterparts elsewhere are "staggered by what goes on here, and saddened and frustrated," Elliott reports. "When I tell them how important it is to track mail returns right away, they say 'Gee, all we've got is one little old lady in tennis shoes who comes in one afternoon a week.' "

Elliott had just finished a speech at a recent national conference of alumnirelations personnel when she was asked what should be the first step in establishing a new alumni-records system. She fixed the

hapless petitioner with an incredulous stare and grumbled, "Find another job."

"There's no way you could start an operation like this now. I can only imagine what Charlotte did the first day she came in, but she probably got in touch with the alumni she knew and asked them what they knew about friends and classmates. But you never could do that today, at another school. For one thing, Dartmouth had only 8,000 living alumni then, one fourth of them 'lost.' "

"Dartmouth's alumni records are unparalleled at any other institution. We try harder, we do a better job but it's no thanks to me," insists Elliott who is given to exaggeration almost as much as she is to grumbling. "I'd like to take credit, but it's because we've always done it from the day Charlotte started the system." In addition, she contends, ARO had going for it in the early days and still has, to a large extent the Dartmouth spirit that makes alumni want to be identified with the College, traditionally strong class organization, and a geographical isolation that fosters close and lasting friendships.

Her claims notwithstanding, not all Dartmouth alumni are eager to be identified with, or found by, the College. "I always heard you guys were hard to get away from, but I never realized how tough it was," one young alumnus complained when Elliott's bloodhounds hunted him down at a new address, almost before he had unpacked his bags. A few have resorted to desperate measures to cover their tracks. One went so far as to report his own death to ARO, which promptly called his employer for particulars. The presumed victim was not only living, the boss responded, but standing by his desk at the moment. He was also fired. "It's not nice to fool Mother Dartmouth," Elliott warns. "Again," she adds drily, "there are a few we're not too anxious to find."

In ARO, where life is unpredictable and rarely dull, Dartmouth yarns flow like beer on Sink Night, always with names deleted to protect the innocent or the guilty. There are the strange name changes and the oddball requests, the small cadre who regrettably can take little part in alumni activities because they are incarcerated "mostly for white-collar crime," says Elliott loyally. And the aging bachelor who asked to be transferred to a class 20 years later, admittedly to spice up a flagging social life. "We could envision the scene a dimly lighted room, with the Alumni Directory on the coffee table and hear the dialogue, 'What, you don't believe I'm 32? Go on, look up my college class.' Then, when he asked to be transferred back a couple of years later, we wondered whether he had found an older woman, instead of a sweet young thing." And the nonagenarian who coveted oldest-living-alumnus status when he called his sole surviving classmate to inquire solicitously about his health, the feisty retort was: "If you think I'm going to die first just to make you the oldest, you've got another guess coming."

What does Elliott like the most about Dartmouth? "I have more men in my life than Bo Derek." And the least? "I have a sneaking suspicion she's having more fun." And "one of the better things," she goes on in a far more serious tone than she ordinarily permits herself, "is my adoption by the class of 1943 and the personal friends I've made that way." For a long time, she hesitated to use the class numerals. "I felt that there might be some hard feelings, particularly with those liberated females coming along and coeducation still a sore point for some of that age group." But, once adoption became more common, she added '43 to her name and put herself on the class list. "Until then, I had never realized how much mail alumni get class dues, newsletters, club notices, bulletins, Alumni College, tours. I'm thinking of putting myself in 'not interested,' just to turn it off." Hastily she adds, "Not really. Never. Once a '43, always a '43."

Pressed for a definition of the typical Dartmouth man, this woman who probably knows more of the species, including dozens of regular correspondents, than does almost anyone else on the campus at first vehemently denies that any such type exists, then proceeds to categorize them by varieties of chauvinism. "You have to divide them by age. In my age group, you have the nice chauvinists who are chauvinists because they are gentlemen. Then you have the younger ones they're just chauvinists because they're feeling insecure because of all the pressure from brainy women."

Elliott grumbles a lot about hard-core feminists and young women who keep their own names after marriage perhaps because she'll soon have to sort them all out for the 1981 directory but she doesn't really knock equality. "I'm right there for equal pay, but I do like to have doors held for me." She remembers when times were different at Dartmouth. She recalls her job interview. "The personnel director asked me what my experience and my salary expectations were. When I told him, he agreed that was reasonable in view of my background, but said, 'Of course, you realize when we have an opening like that, we offer it to a Dartmouth man.' There was no question about it, and I accepted it just the way he did. If that's it, that's it. Then, about three months later, he called back and said, 'The only possible slot where we could work in a female officer happens to be in Alumni Records, and the woman who's there now is leaving."

Where most non-Dartmouth administrators follow job opportunity to Hanover, then fall in love with the north country, Elliott typically put the cart before the horse. She rides around town in a big car with New Hampshire license "WV-NE," for Waterville Valley next to Dartmouth men and four-legged animals, the love of her life. She was working in Boston when she built her house and then, finding the weekend commute too long, decided to get a job closer by.

"I have a very satisfactory life here, and I'm probably rotten spoiled," says Elliott cheerfully, "and that's got to be one of the things I like about Dartmouth. I have a nice place in Waterville, a nice condo in Hanover. My boss is really probably too nice to me don't tell him that and I have a tremendous amount of freedom."

"There's a saying in the trade: 'There way be more money in fund-raising, but the fun is in alumni affairs.' I think about that when I look at my paycheck."

WEARERS OF THE GREEN

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Trapper, the Beaver, and the Cold Country

March 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

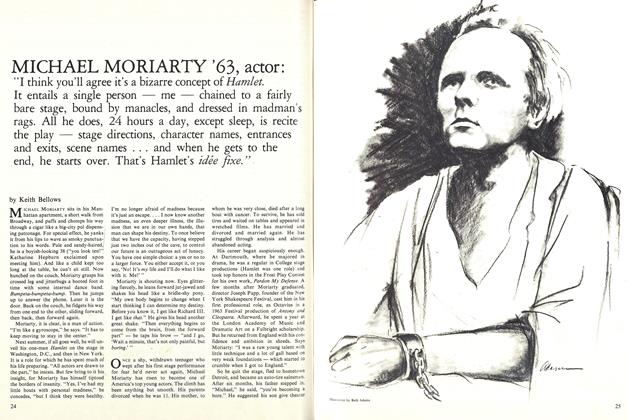

Cover StoryMICHAEL MORIARTY ’63, ACTOR

March 1980 By Keith Bellows -

Feature

FeatureManaging Dartmouth’s Money Slide Turns to Rally

March 1980 By Dero A. Saunders -

Class Notes

Class Notes1913

March 1980 By CARL C. FORSAITH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

March 1980 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

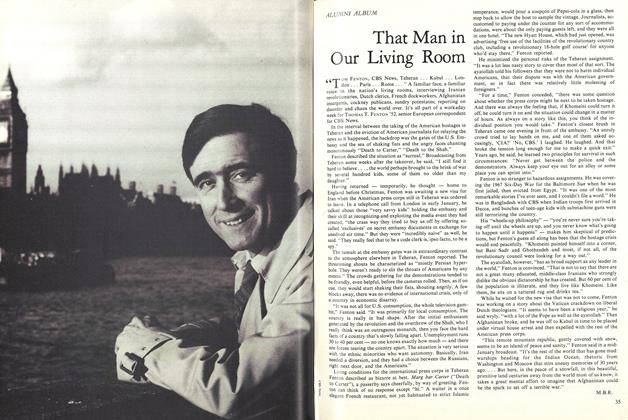

ArticleThat Man in Our Living Room

March 1980 By M.B.R.

M.B.R.

-

Article

ArticleConservator by Design

February 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleM for Mystifier

March 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleFalling Dominoes

October 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleEqual Opportunity: efforts to make it more equal

June 1976 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleSky Watcher

JAN./FEB. 1978 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleKeeper of the College Attic

MAY 1978 By M.B.R.

Article

-

Article

ArticleSummer School Announcement

May, 1911 -

Article

ArticleBetween Two Holidays

JANUARY 1929 -

Article

ArticleDouble Honors

June 1955 -

Article

ArticleBehind the Barn Door

JULY | AUGUST 2015 By —Theresa D’Orsi -

Article

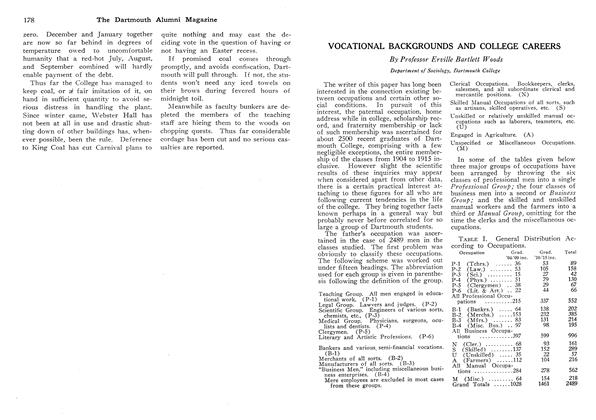

ArticleVOCATIONAL BACKGROUNDS AND COLLEGE CAREERS

February 1918 By Erville Bartlett Woods -

Article

ArticleFaculty Books

October 1953 By LEONARD W. DOOB '29