My interest in high altitude is mostly practical. While I was a student, and for a couple of years following graduation, I spent my summers working as a climbing guide on Mt. Rainier, a 14,410-foot glacier-covered volcano in Washington, where exposure to oxygen deficiency was sometimes a problem. The two-day Climb started just below 6,000 feet, and most of our customers showed up the first morning only a few hours after leaving their homes near sea level.

After a five- or six-hour trudge up four miles of steeply inclined snowfield, the climbers reached a hut at 10,000 feet where they were fed, watered, and put to bed-only to be rousted from their sleeping bags at one o'clock in the morning. Most people hadn't slept well, a few complained of headaches and nausea, and hardly any were enthusiastic about the pre-dawn breakfast of instant oatmeal and lukewarm cocoa.

During the seven or eight-hour climb to the summit, the most important thing a climber had to do was breathe-sometimes two or three breaths between every step. It sounds simple, but a conscious effort to sustain deep and regular breathing, forcing each exhalation, often seemed to make the difference in whether or not a person reached the summit and enjoyed the climb. People who let up-those who reverted to shallow and irregular breathing patterns-frequently had to turn back because of exhaustion or illness. There certainly were other factors involved, but a middle-aged desk-jockey who breathed tended to outlast a college athlete who panted. Seeing people who had difficulty on Mt. Rainier made some of us wonder how we would perform at higher elevations.

I had the opportunity to find out on Mt. Mckinley in 1978, when I was with a group of climbers who spent five storm-lashed days cooped up in small tents at 18,000 feet. We had done all the right things to avoid acute mountain sickness during our two-week climb from about 7,000 feet. To permit time for acclimatization, we held our rate of ascent to an elevation gain of only 1,000 feet a day. We took occasional days off from the work of moving loads of supplies up the mountain, each of us made an effort to drink almost a gallon of fluids a day to combat dehydration, and we consumed a balanced diet of more than enough easily digestible calories. On the occasions when we had to spend two days making trips between camps, we slept the first night at the lower elevation. Until we reached our high camp, only three or four people in the ten-man party experienced any symptoms of mountain sickness, but after a night or two at 18,000 feet, we all complained of headaches, varying degrees of nausea, loss of the sensations of appetite and thirst, and sleeplessness.

Last summer, after spending nearly two months at about 18,000 feet on Mt. Logan in the Yukon Territory, eight of us who were research subjects in a high-altitude physiology study were able to say we experienced hardly any illness related to altitude. (The research project, under the direction of Dr. Charles Houston, a veteran mountaineer and member of the medical faculty at the University of Vermont, has been an almost annual undertaking for the past decade. It also has involved several Dartmouth alumni, including Bill Brinton '75 and Ward Cheney '76 in the summer of 1976.) We started our ten-day climb to the high camp several days after flying from near sea level to a base camp we established on a glacier at 11,000 feet. Once we started the climb, instead of moving camp 1,000 vertical feet up the mountain each day (the practice on Mt. Mckinley the summer before), we split the loads in half and spent two days carrying our supply of food and equipment between camps spaced further apart. We would climb 2,000 feet one day and make a cache, then return the next day with the remainder of our gear and set up our tents.

Above 14,000 feet, some people felt slight headaches and one or two had days when they felt listless, but no one was seriously discomforted. The most difficult day of climbing was the time three of us carried heavy loads from our camp at 16,000 feet to Prospector's Col, a pass just above 18,000 feet, but it seemed we were fighting the weight of our packs and the force of a wind occasionally strong enough to knock us off our feet as much as we were struggling with the altitude. Two days later, in good weather, when the entire party of six men and two women crossed the pass to the Logan Plateau where our high camp and the laboratory were to be established, we felt only the effects of a hard day's work at a high elevation.

During the next couple of weeks, we further acclimatized to the altitude while building the camp and setting up the laboratory. We had a two-year-old supply cache to dig out of the glacier, and the top of the two-story plywood hut containing the supplies, was buried under more than 20 feet of snow. As we dug down, the snow turned to ice and we alternately had to chip with our ice axes and scoop with shovels. As the hole got deeper, a series of large steps had to be excavated to relay the snow to the surface. It was strenuous work, and even a person who established a slow and steady pace was soon breathless and had to be relieved. Light activities oe would ordinarily perform at sea level without noticing the effort-lacing boots in the morning, taking a photograph, or threading a needle-showed us how dependent we were on oxygen because those are occasions when a person tends to hold his breath, at least for a moment. Gulping for air after taking a picture was a new experience, and one was repeatedly reminded of ways that life at altitude was different from life at sea level. Mental processes didn't seem to be affected to the extent that I noticed on Mt. McKinley, where my ability to put thoughts into words seemed to bog down, but ordinary mental, physical, and emotional responses to the situations of daily living required more effort. As time went on, we noticed the differences less, although there still were limits to what we could do.

We rewarded ourselves with a climbing vacation after excavating the cache and constructing the camp, which consisted of large, double-walled tents set on plywood platforms. During the two-day climb from our base to the summit, we frequently found ourselves taking several breaths with every step. A long trudge across a wide, flat plateau seemed excrutiatinly slow, more difficult than climbing a steep section where maintaining a steady pace and breathing pattern seemed more natural.

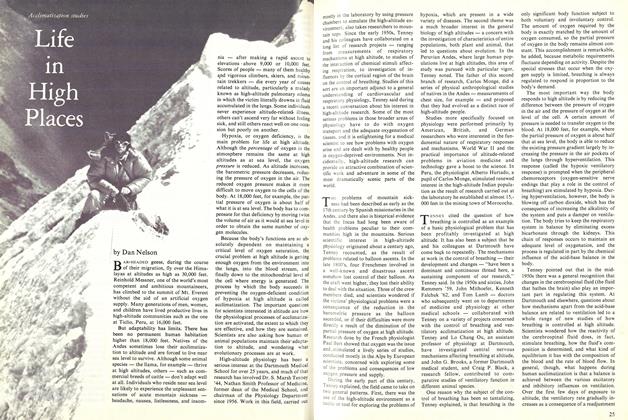

Throughout the remaining weeks at high camp, no matter how much we tried to keep fit by skiing or climbing while the weather permitted, extricating our supply plane from snow drifts on the occasions when it was able to land pushed us close to our limits. When the plane bogged down in the snow while attempting to take off, we turned it around and hauled it back up the glacier by pulling on ropes attached to the wings while the pilot revved the engine. It once took an entire day's work to get the plane in the air, and after each session of straining against the ropes and floundering in deep snow, people would fall to their knees exhausted and gasping for breath.

We were well acclimatized by the time we descended in July after spending almost two months on the mountain. Our stay had been prolonged by a series of storms that prevented the arrival of scientists and additional research subjects to the high camp, and the logistical problems forced a cancellation of studies at the high-altitude laboratory. We were anxious to get back to the thick air of the lowlands, but there also was a sense of irretrievable loss in leaving the mountain-top environment and the camp we had worked so hard to build.

D.N.

Helping a plane take off from 18,000 feet was the hardest job for research subjects who spent two months on Mt. Logan.

Helping a plane take off from 18,000 feet was the hardest job for research subjects who spent two months on Mt. Logan.

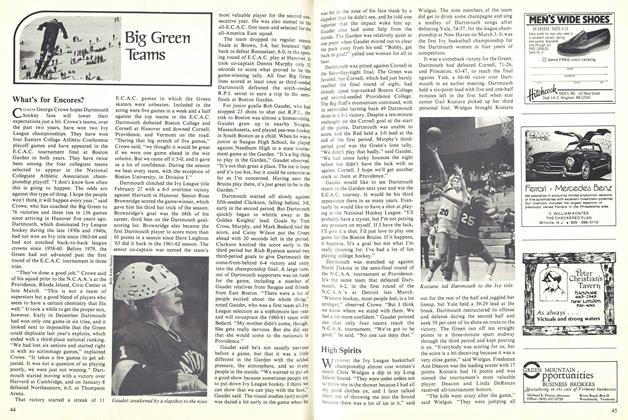

A climber pedals to exhaustion on an exercycle after descending from 18,000 feet.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMaking Books

April 1980 By Robert H. Ross -

Feature

FeatureLife in High Places

April 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureExtra Credits & Bonus Points

April 1980 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleWho in Hell Was Jeff Tesreau?

April 1980 By Edward D. Gruen '31 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

April 1980 By DAVID R. BOLDT -

Sports

SportsWhat's for Encores?

April 1980

Article

-

Article

ArticleRESIGNATION OF COACH CAVANAUGH

March 1917 -

Article

ArticlePETITION CIRCULATED FOR BUILDING REGULATIONS

August, 1925 -

Article

ArticleSTUDENTS AND CIVIL RIGHTS

MAY 1965 -

Article

ArticleHouston

January 1942 By Dwight J. Edson '18 -

Article

ArticleThe Student Days of Richard Hovey

February 1951 By EDWARD C. LATHEM '51 -

Article

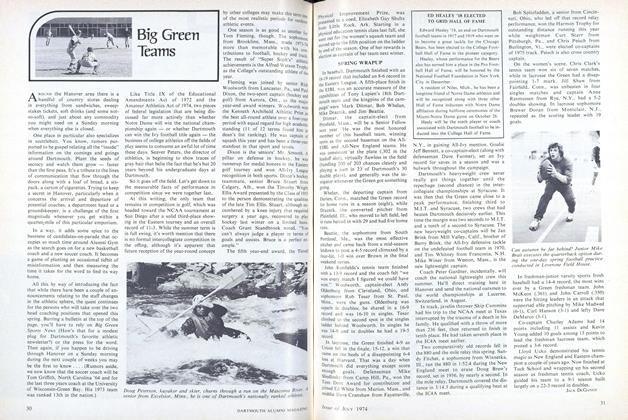

ArticleBig Green Teams

July 1974 By JACK DEGANGE