Winning the close ones

I have been asked that question a lot of times. Last summer I wrote to the editor of the Washington Post, about Dartmouth-and New York Giant-great, Jeff Tesreau Ever since, I've been hearing that question, even from sportswriters in the press box at the Baltimore Orioles stadium. Dartmouth alumni of a certain vintage know for sure who in hell Jeff Tesreau was, but some comparative youngsters may not. So I'm going to tell them.

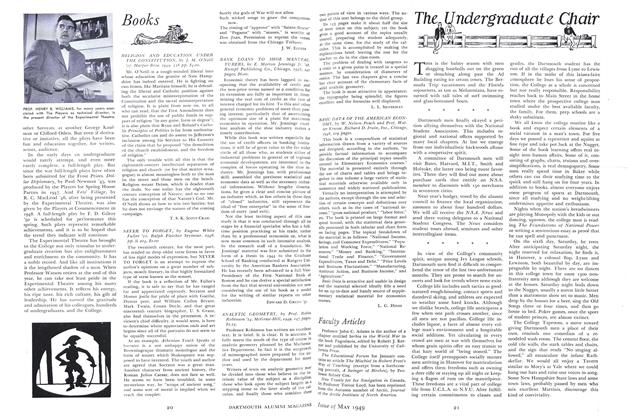

A quick answer would be to say that he was a Giant of a man. That would cover his size-6 feet 4 inches and 265 pounds-and his professional affiliation. Back in the second decade of the century-1912-1918, to be exact-right-hander Tesreau was one of the "Big Four" that manager John McGraw had pitching for him. The others were Christy Mathewson, Rube Marquardt and Bugs Raymond. (Jeff roomed with Bugs, according to Giants' star third baseman Buck Herzog because he could handle that eccentric "flake" and notorious sleepwalker.)

Another part of the answer would be that Jeff Tesreau was "one of nature's gentlemen," a true tribute I owe to my 1931 classmate Monroe Karasik founder and senior partner of an international law firm based in Washington, D.C. Karasik was by no stretch of the imagination a frustrated "jock"-and as I admittedly am-nor did he even read about sports much. But he did know Tesreau intimately. The chemistry between the Brooklyn scholar-night owl type and Jeff, the "Ozark Bear," was made up of one-part love of yarns and the spinning thereof, one part practical jokes, and one part just staying up late. In Hanover, that meant any time after 11:00 p.m., when the last call for "toastsides" went out.

And then there's the Baseball Encyclopedia's answer. Tesreau won 118 games and lost only 72 in his seven years with the Giants. He pitched 123 complete games, 27 of them shutouts, and recorded an overall 2.43 earned-run average. As a rookie (brought up from the minors for the magnificent annual salary of $1,800), he won 16 and lost 7 and set a long-standing record by pitching a no-hitter in his first year, giving the Giants a big boost toward the pennant. The following two years, 1913 and 1914, which brought the Giants another pennant and then second-place to the Braves, he won 22 and 26, respectively. Though 1915 was a dismal year for the Giants-they ended up in the cellar, losing Marquardt part way through Jeff Tesreau's name shines bright in league records: tied for second in shutouts (8), third in innings pitched (306) and fifth in complete games (24).

Perhaps Tesreau was proudest of the 1915 season, struggling against the odds. It may have been the inspiration for what came to be known-around Dartmouth, at least-as Jeffs rule: "All I ask of life is my share of the close ones." It was this I had in mind when I was asked more than 30 years ago to compose the inscription for the tablet to Jeff at Rolfe Field.

Christened Charles Morton Tesreau but known universally as Jeff-on account of his resemblance to Jim Jeffries-he died in September 1946, about two years before I returned to Hanover to teach at the Tuck School. He and his long-time friend and fishing companion, athletic director Rip Heneage were settling in for three days of camping and fishing at Reservoir Pond in Lyme. They were transferring gear from car to rowboat when Tesreau bent over to unlock the chain on the boat and suffered a sudden stroke, pitching forward into shallow water. Rip managed to pull him out and get him to Dick's House, where he died five days later. This close one Tesreau lost-as we all must, some day.

Opinions vary about why he gave up the excitement of the big leagues for a small town and a small college-no matter how much beloved by Daniel Webster and a lot of other alumni. Eddie Jeremiah '30, who played second base for Jeff as an undergraduate and came back to coach hockey for some 30 years, recalled that the relationship between McGraw and Tesreau iced over after Jeff refused to snoop into off-field activities of players he was supervising at training camp. Others think the "Ozark Bear" simply wanted something better for his family.

His wife Helen agreed to the move, although she told me some ten years later that north-country quiet was scarcely her first choice. It was green all right-and too quiet. How was a young woman from the Bronx, used to being lulled to sleep by the "El," to get along with nothing noisier than crickets? But Jeff had his way, of course, and when the offer came, he took it. And he was thinking mostly of his three-year-old son Charlie not Junior, he was Charles Francis. For him he dreamed of a college education, and where better than Dartmouth! And Charlie Tesreau did grow up in Hanover and did graduate from the College, in 1938. After law school and service with the F.8.1, and the Marine Corps, he returned to Hanover and practiced law in Lebanon as a partner of Senator Norris Cotton until his death in late 1978.

None other than Ernest Martin Hopkins testified to Tesreau's devotion to his family and the College in a letter he wrote Charlie after Jeff's death. Recalling that track coach Harry Hillman had suggested, not long after Jeff's appointment, that the baseball coaching job be made permanent rather than seasonal as it had been, the president wrote that he decided to return to Hanover during the summer to talk the matter over.

"Driving back from Maine for the engagement," Hopkins wrote, "I picked up a Boston paper and read under big headlines that the Braves had sent a contract to your father, having at length after long effort secured his release from the Giants. The figure quoted was so far outside the range of academic salaries that I was tempted to turn back, doubting if your dad would even want to keep the appointment in view of the sudden turn of events. ..."

But the two men did meet, and the president told Tesreau that the College couldn't possibly meet the Braves' offer. Jeff said he and Helen had figured out what they needed to live on and, if the College could pay it, he'd come to work full time. "I have forgotten the figure," Hopkins wrote, "but it was a modest one. I then told him that we could and I thought we would meet that, but first I should like to know what he thought Dartmouth offered in the way of possibilities that made him willing with your mother to forego the financial advantage of the Braves' offer. I loved him right off for his answer, 'I want my little boy to grow up in surroundings like this, and an opportunity to have him do so is worth more than any money to me.' "

By 1929, Tesreau had the Big Green at the top of the Ivies. They were not crowned champions that year because the league did not play a home-and-home schedule in all cases. But, by the time the 1930 season rolled around, a full schedule of 14 games was played by each of the eight Ivy League colleges. And Jeff got his wish-winning his share of the close ones-as the Dartmouth nine repeated its dominance of eastern diamonds. Captained by catcher Bart McDonough '3O; inspired throughout the season by the major league-class play at shortstop by Red Rolfe '31, who teamed up with Jeremiah for a record number of double plays; and blessed with two strong pitchers, Gunnar Hollstrom '30 and Lauri Myllykangas '31, both good enough for big-league tryouts-that team even overcame the jinx of being heralded as "sure repeaters."

The game that decided the championship was against Cornell, played fittingly enough on commencement day. To win outright and avoid a tie with Penn, Dartmouth had to win its last game. And Cornell was no patsy, with a brace of strong, healthy hitters and star pitcher Bob Lewis rested and anxious. The first eight innings were scoreless as the Big Red hurler matched the Green's Hollstrom pitch for pitch. So was the ninth-but not until some heroics by Myllykangas and Rolfe kept it so. Cornell's heavy-duty hitter Glen Cushman finally got hold of one and rode it a good 400 feet into the gap between left and center. Myllykangas-in the lineup at center field mostly for his bat-gave chase and threw it in to Rolfe at short left on the fly. Rolfe then wheeled and fired a bullet on one hop into McDonough's glove. The perfectly timed relay caught Cushman out by only one or two strides.

So the game went into an extra inning, and tension mounted in the crowd of 2,500 spectators, large then and now for college baseball. Even the major-league scouts who were on hand-for the Boston Red Sox, the Yankees, and Connie Mack's Athletics-were impressed, as they told us later. But the suspense was soon over. In the bottom of the tenth, "Mylly" had one last swing, and he caught a beauty, right on the nose to right field. Hard hit? It was still rolling in the general direction of the lacrosse field when the gorgeous Finn rounded third. The final score: Dartmouth I, Cornell 0, in ten innings. Among the records established: number of double plays by one team-Dartmouth, four in the regular game; five, counting the extra inning.

That's what Jeff Tesreau meant by winning his share of the close ones-play hard and clean, especially in the late innings. And, more often than not, the breaks will come your way, giving you two out of three, maybe, or even three out of four. What he didn't mean was ever being content with just a shade over .500 ball. It is clear Tesreau would never have agreed with the likes of Vince Lombardi and George Allen, that "Winning is everything" and "To lose is to die."

No, the Giant who was one of nature's gentlemen and a good family man to boot knew better. As Al Smith would have it, "Just look at the whole record." For Charles M. Tesreau-Jeff to us all-that's what his onetime student manager has just tried to do.

The Ozark Bear relaxes in the Dartmouth dugout with two of the Hanover faithful.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

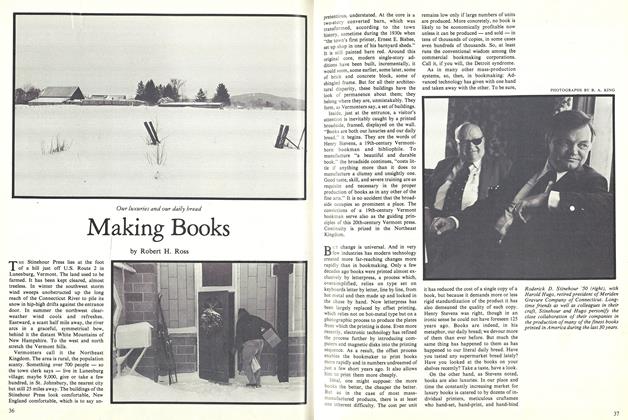

FeatureMaking Books

April 1980 By Robert H. Ross -

Feature

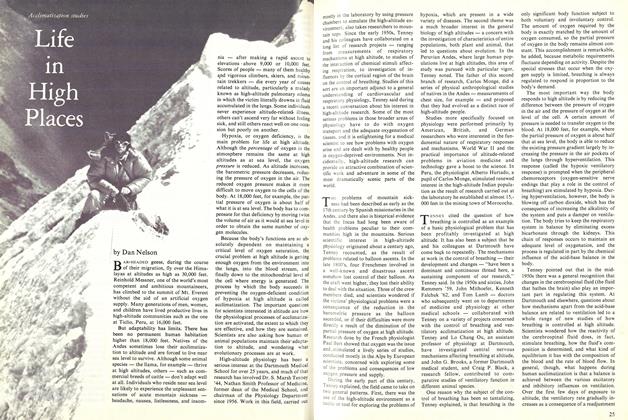

FeatureLife in High Places

April 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

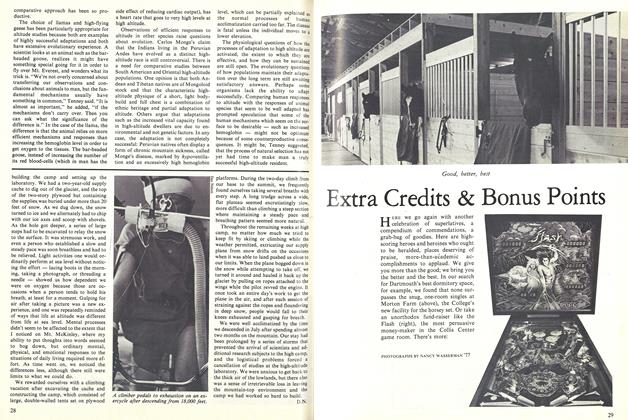

FeatureExtra Credits & Bonus Points

April 1980 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleAdapting to the Heights

April 1980 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

April 1980 By DAVID R. BOLDT -

Sports

SportsWhat's for Encores?

April 1980

Edward D. Gruen '31

Article

-

Article

ArticleNew Dartmouth Movies

December 1932 -

Article

ArticleCo-Authors

FEBRUARY 1963 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse for

MAY 1984 -

Article

ArticleReflections of a Dickey Intern

NOVEMBER 1984 By Diana Shannon '85 -

Article

Article"To the conquest of the unknown and the advancement of knowledge."

MARCH 1984 By Mary Ross -

Article

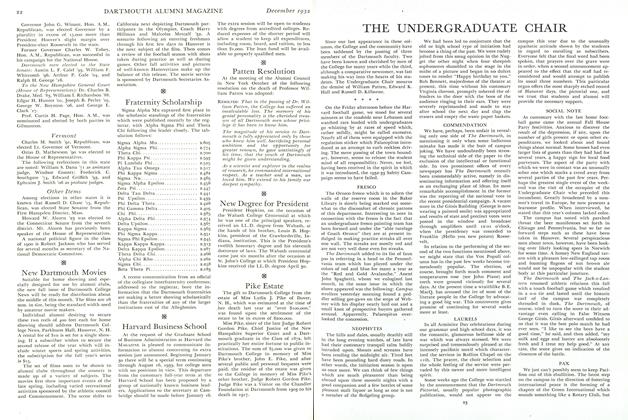

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chail

OCTOBER 1969 By WIN ROCKWELL '70