Dave Goodwillie can claim distinction in several regards. For starters, to the best of your secretary's knowledge, Dave is the lone man of the cloth in the class. Almost certainly he is the only member "of the class who is a minister, and who was a Marine infantry platoon leader in Vietnam. Moreover, he tells me that as far as he knows, he is the only Unitarian chaplain in the United States Army.

(Unitarianism, for you delinquent scholars of doctrine, is a small Protestant sect that is currently in a period of eclipse. This is in part because of its belief that matters of faith are subject to rational and conscious discourse, and don't necessarily have to be relegated to an altered state of consciousness a point of view that doesn't mesh with the times. And perhaps at this point your secretary should admit to being a co-religionist of Dave's.)

Anyway, I reached Dave at Fort Campbell, Ky., where he is currently the chaplain to a 650-man battalion of the 101 st Airborne Division, known as the "Screaming Eagles" or, sometimes, to the irreverent (Dave tells me), the "Puking Buzzards." What I wanted to know was how he made the switch from combat leader to spiritual leader.

It all began in Vietnam, he told me, but it was not a case of a foxhole conversion. "It wasn't a conversion," he said, "it was a process." It began in the internal conflict he felt "between having to be a hard-changing combat leader on the one hand, and caring for the youngsters that had been placed in my charge on the other."

Possibly the idea of being a minister had been with him before his three years in the Marines, he continued, though he grew up in an environment of "comfortable agnosticism." The big problem, he says, is that "I didn't relate to the typical religious idea of the pious preacher, the man of the cloth." In Vietnam, however, the chaplains he met were people who did not fit the typical image of the minister. "They were folk I related to very well. They were performing a caring service. They were intensely involved in the lives of people." And they were helping at times when help was really needed.

Still, the process by which he became a minister was not a smooth, straight-forward transition. "I resisted it," he says. "Every time I took a step in the direction of the ministry, I would recoil and take two steps back away from it."

Leaving the Marine Corps as a captain after three years, which had also included a tour in Europe following his Vietnam experience, Dave came back to Boston and tried a number of things. He was a reporter for the Quincy, Mass., Patriot-Ledger, attended Northeastern Law School for a day, worked in the public relations department of John Hancock Life Insurance Company, earned a master's in educational guidance at Tufts, taught high school English, and got married. (Dave and his wife Kristin have a daughter Trucia, now seven.) For about a year somewhere in the late sixties Dave also worked in Los Angeles for the Office of Naval Intelligence.

Throughout all of this Dave found thai "whatever I tried, I ended up on the.wrong side of people. I wanted to help them, and I kept getting into adversary relationships." Among other things, he found that his war experience tended to estrange him from the students he taught and went to school with at Tufts. It wasn't that he wanted to defend the war. In an experience he says was very similar to that outlined by Philip Caputo in the book Rumor ofWar, Dave says that by 1969 he no longer believed that American policy in Vietnam was right, but he still found himself "defending the people I was with, and the fellowship we had known." Also, the lack of patriotic commitment among those around him bothered him. "I was still a Kennedy American," he says. "I hung onto a lot of that."

During this period, he became involved in the activities of the Arlington Street (Unitarian) Church in Boston, and responded to the message being delivered there by a particularly engaging minister. He decided that he would give the ministry a try, after all.

The rest of his career proceeded along a somewhat straighter line. He completed the three-year theological program at Star King Seminary in Berkeley, Calif., in two years, then returned to New England, where he was briefly an instructor at the Hurricane Island Outward Bound School in Maine, before becoming the minister of the First Parish Unitarian Church in Kennebunk, Maine, where he remained for the next three years.

Dave left there to devote full time to a program he had already started at Andover-Newton Theological Seminary aimed at earning a doctorate in pastoral counseling, which he Finished a couple of years ago. At that time, he was offered the job as minister for the Unitarian Church in Salem, Mass., one of the oldest churches in America (1620), and something of a prestige assignment in Unitarianism. But he decided against it. "What they really wanted was a curator more than a minister," he says.

What he decided to do was to re-up. He joined the Army as a chaplain, and was assigned to the 101 st. By and large, Dave likes it. "It involves more dealing with people and less churchmanship beating the drum for people to come" and keeping track of budgets and staff. In fact, he preaches at one of the base chapels only once every five or six weeks, which is just as well, he feels, because he isn't sure how well his Unitarianism goes down in Kentucky, which is real lectern-thumping, ten-finger C-chord, Sister-Martha-at-the-Yamaha, Bible Belt country. (And, for that matter, Dave finds that the born-again, fundamentalist spiritual ambiance goes a little "against my grain" as well.)

He finds plenty of opportunities to help people though, on matters ranging from marital difficulties, through homosexuality, to alcohol and drug abuse. "I try to be an advocate for them," he says of his relations with the troops he counsels, "and to get them to stand up as individuals." He finds that he becomes almost a "parent figure" for some. The all-volunteer Army, he has found, "has a lot of people in it who are educationally and emotionally marginal, who do not have adequate adult coping skills in a lot of situations." (Even so, he says he is "congenitally opposed to a [resumption of the] draft.")

When not counseling and preaching, Dave is often running, and has posted a four-hour, 15-minute marathon clocking, which by my reckoning makes him third in the class.

In closing, newsletter editor Dave Schaefer passed along the following late-breaking bulletins:

The Greg Cooke family of Gladwyne, Pa., added a son to its roster when Joshua Cooke was born on Thanksgiving. Al Davies reported from New York that "life is super" and "business excellent." His real estate management company is currently at work on a consulting project for Co-op City, the largest complex of residential apartment buildings in New York (or the world, for that matter), with 55,000 people living in 15,300 apartments. For various reasons, the natives have been restless there of late, suffering pangs of anomie, or whatever, and Al is apparently trying to get to the bottom of the problem. Al was also up at Lake Placid, where he was head of operations for the ceremonies and awards division. (No, he had nothing to do with the buses.) Sam Cabot says he thought "you'd never catch me going to Harvard," but nonetheless he will be attending a small-company management program there this winter. Sam, as loyal readers of this column know, is president of the company that bears his name, a family corporation that has made quality stains, varnishes, and related products for centuries.

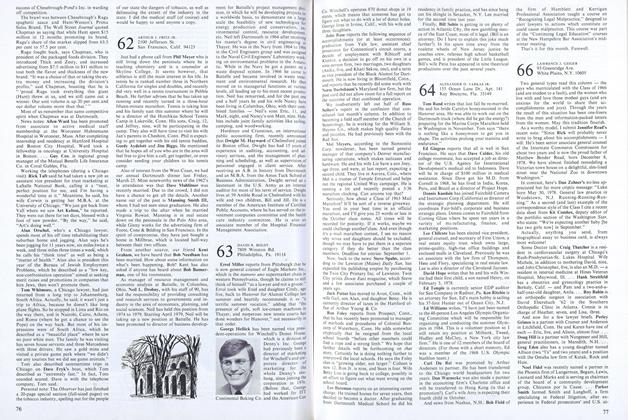

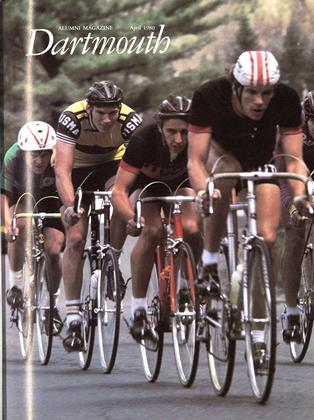

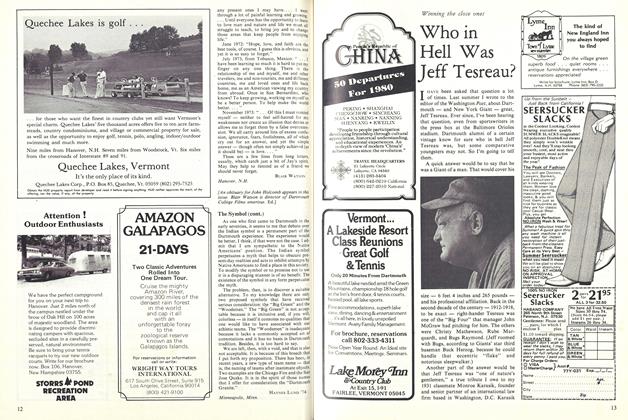

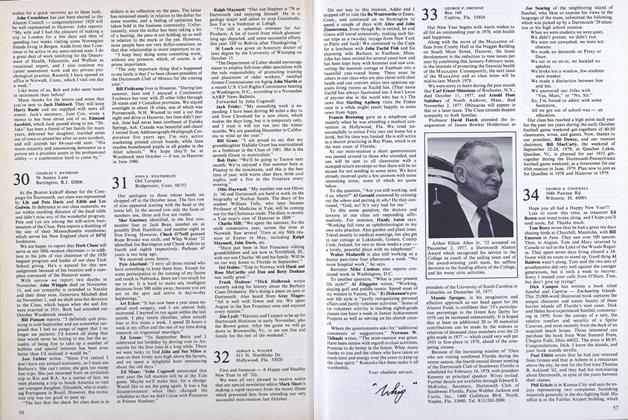

Two members of the class of 1963 were at a recent White House reception honoring the U.S. Winter Olympic teams. On the left is Michael Cardozo, deputy counsel to the President, with Jim Page, assistant director of the U.S. Nordic ski team and a former ski coach at Dartmouth. Among those he coached during his six seasons in Hanover-1972 to 1978-were the four Big Greeners on the U.S. Olympic ski team: Walter Malmquist '78, Doug Peterson '75, Don Nielsen '74, and Tim Caldwell '76.

7809 Winston Road Philadelphia, Pa. 19118.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMaking Books

April 1980 By Robert H. Ross -

Feature

FeatureLife in High Places

April 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

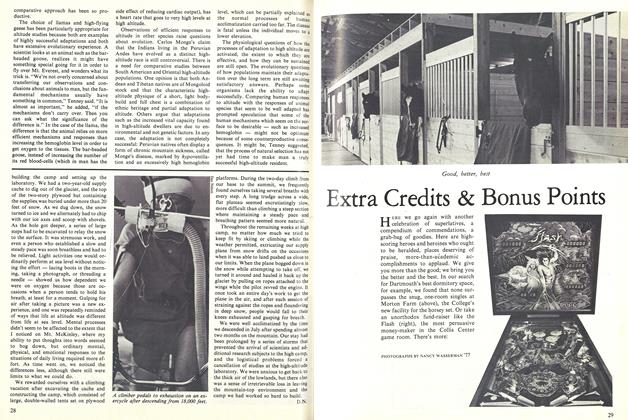

FeatureExtra Credits & Bonus Points

April 1980 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleWho in Hell Was Jeff Tesreau?

April 1980 By Edward D. Gruen '31 -

Article

ArticleAdapting to the Heights

April 1980 -

Sports

SportsWhat's for Encores?

April 1980

DAVID R. BOLDT

Class Notes

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1895

April 1918 By Ernest S. Gile -

Class Notes

Class Notes1928

March 1993 By George A. Bell -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

November 1960 By GEORGE B. REDDING, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

JAN./FEB. 1978 By JOHN S. WEATHERLEY -

CLASS NOTES

CLASS NOTES2020

MAY | JUNE 2023 By Katie Goldstein -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

February 1947 By ROBERT D. SALINGER, HERBERT F. DARLING, ROBERT M. STOPFORD