On June 14 of this year, directly after commencement, James E. Randolph '81 was commissioned a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Reserves, the first Dartmouth student in a decade to complete an R.O.T.C. program.

Later that week, DAVID G. HARSCHEID '56, captain U.S.N., deputy chief of staff for technical warfare readiness, submarine force, Atlantic Fleet, in town for his 25th reunion, recalled his own commissioning, when 63 Navy ensigns and 30 Air Force and 18 Army second lieutenants received their gold bars.

When the College decided to phase out the R.O.T.C. program, Harscheid, who only last month became commanding officer of the San Diego, California, submarine base, called it "a tragic error in judgment." "Effective leadership in the military," he declared, "cannot be the product of a few 'Service Academies.' To produce a balanced and effective management corps, the men of Dartmouth, Stanford, and the University of Kansas must bring their varied influence into the business of national defense."

He stands by that credo today. The loss of liberal-arts graduates to the military is a "a tragedy for the country," Harscheid maintains. To avoid a stereotype, "the Navy or any other organization needs a wide variety'of opinions and backgrounds. In the first formative years of a career, you bring together people from the Naval Academy, Penn State, Stanford, and Dartmouth College, and they form each other. In ten years, you can't tell the difference between them, but they are a more liberal conglomeration, having exchanged ideas between them."

A career in the military was still far from young Ensign Harscheid's mind that rainy June morning in Hanover. Straight into the-sea-going Navy, first on destroyer duty, "I sailed north of the Arctic Circle, into the Red Sea, to South America, and I had an absolute ball," he recalls. He first encountered the submarine service at anti-submarine school. "As part of it, I had to go ride a submarine, and I discovered that those guys were neat. I figured if they were fighting me and I was fighting them, I was on the wrong side of the fence." Application for submarine school, which required more than minimum service, became inevitable. Espris on the submarines was exceptional, Harscheid found. "They were super people, true professionals who worked hard, played hard, and had a lot of fun. There was about 95 per cent officer retention, and I was rapidly getting hooked."

Harscheid served first on diesel submarines and "then a thing called nuclear power came along, and it became obvious that that was the submarine force of the future." Accepted for nuclearpower school, he completed Admiral Rickover's training course of six months graduate-level work in mathematics, chemistry, and physics, followed by six months at a shore-based Navy reactor site before reporting as part of the commissioning crew of the NathanHale, an early Polaris-class submarine.

Of all his tours of duty one destroyer, six submarines, a submarine marine tender, squadron staff, force commander's staff Harscheid gloried most in command of the tender Dixon. A floating repair and service facility staffed by 1,250, she was like a self-contained city, prepared for anything that didn't require a drydock. "We had foundries, machine shops, dental care, operating rooms, a dry-cleaning plant; we had the baked beans and the toilet paper." Operating on short tours out of San Diego, the skipper's all-time favorite city, the Dixon offered the best of both worlds sea duty and frequent shore time with his family. "I've been fortunate," he says. "In 25 years in the Navy, I've never been stationed in Washington, D.C., and I've never been very far from being at sea or directly operating ships or controlling them. Now I'm too old for sea command, and I'll miss it," he adds a trifle wistfully. "Maybe I've never grown up, but there's little more fun than driving a ship or flying an airplane."

On his last assignment in Norfolk, Virginia, Harscheid was responsible for readiness, tactics, and training for Atlantic Fleet submarines. He was concerned with fire control "I don't mean putting out fires, but aiming the computers that compute what the other ship is doing and how to place weapons on that ship" with sonar systems, and with the weapons themselves.

Digital computers, he explains, have brought a revolutionary, not an evolutionary, change in the Navy's capabilities. "And digital technology is giving a lot of people a lot of problems, particularly people like me. Two years ago, I really was one of the expert submarine tacticians in the United States Navy, then all of a sudden instead of a bunch of dials, buttons, and knobs, I have a video screen and a keyboard. I understand the problem I'm trying to solve, but I don't understand the equipment I have to solve it, and learning is a slow process." Junior officers just coming in, on the other hand, understand the equipment, but not the problem. And the problem, he adds, is not something they can learn in a year or two. "A lot of it is intuitive; a lot of it is value judgment."

Digital technology is not the only aspect of the "new Navy" that Harscheid finds disquieting. There's the image of the military that remains a legacy of Vietnam. There are discipline problems and morale problems. There are women in the Navy, about whom he has mixed emotions: "The first women officers reporting to a ship were superior, and they did a super job. But we've gone too far." There's the all-volunteer service that has "dramatically affected the quality of people coming in. We need the draft. The answer is not to raise salaries so high they're more than competitive. It won't work to make it merely a mercenary thing."

"We've become a nation of individuals with individual rights, but society can not survive if we're always trying to serve the individual. There's got to be personal sacrifice." What concerns Captain Harscheid most, he says, is that "to be in the military, you have to believe in some sort of patriotism. It's that simple."

AT the end of July, Mexican writer and diplomat Carlos Fuentes brought to a close his seven months at Dartmouth as a teaching fellow under the Montgomery Endowment established by Harle and Kenneth Montgomery '25. Fuentes, son of Mexico's ambassador to Holland, Panama, Portugal, and Italy, was born in Mexico City and attended primary school in Washington, D.C. His law degrees, taken in Mexico and Switzerland, were followed by a period of public service in Mexico during the fifties, when he also founded two Mexican journals, one political, one literary. He published his first novel, La Region Mas Transparente (Where theAir is Clear) in 1958, and it has been followed by nine others, among them the highly-praised La Muerte de Artemio Cruz (TheDeath of Artemio Cruz), a technically dazzling review of the tortured life of a corrupted Mexican revolutionary. He has also published two plays, several short-story collections, the most recent of which is the best-selling Burnt Water, and a number of literary and political essays. From 1974 until 1977, Fuentes served as Mexico's ambassador to France. Since then he has spent most of his time writing and teaching in colleges and universities in the United States, from New Hampshire to South Carolina and Virginia to California.

Currently married to Mexican journalist Sylvia Lemus, Fuentes is the father of three children, two of whom were besieging him when I arrived at Montgomery House late on the afternoon of July 29. Fuentes had agreed to a last-minute interview amidst the chaos of packing up for his return to Mexico, and he himself opened the door, looking, at 52, markedly trim and casual. In fact, the graying author retains a good deal of the cockiness of young manhood. He shooed the children off, apologized for the domestic flurry, and opened the floodgates of his mind. I scribbled frantically under the pressure of a torrent of rapid-fire observations delivered in unhesitating English. The whole thing took only 20 minutes, and my pencil died of exhaustion during the first five. Here, then, courtesy of the tape recorder, are the galloping ruminations of the author of The Death of Artemio Cruz.

SHELBY GRANTHAM

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryJust a suggestion, Mr. President: an agenda for the eighties

October 1981 -

Feature

FeatureCarlos Fuentes: Of isolation, of connection

October 1981 -

Article

ArticleDeaths

October 1981 -

Article

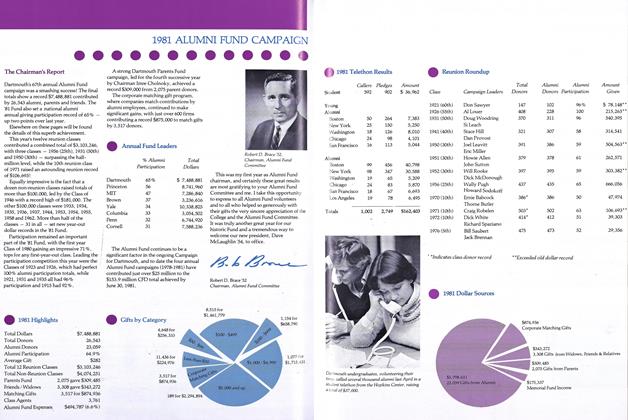

Article1981 ALUMNI FUND CAMPAIGN

October 1981 -

Article

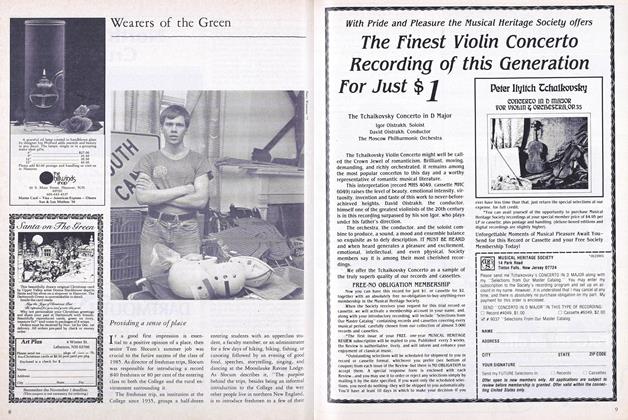

ArticleWearers of the Green

October 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

October 1981 By Michael H. Carothers

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Recent Interview with Ernest Martin Hopkins' 01

APRIL 1991 -

Feature

FeatureGISH

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Brad M. Hutensky '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryAmerican Patriot

MARCH 1995 By Christopher Wren '57 -

Feature

FeatureReunions, 1970 Style

JULY 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureHow Much Government?

March 1954 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Feature

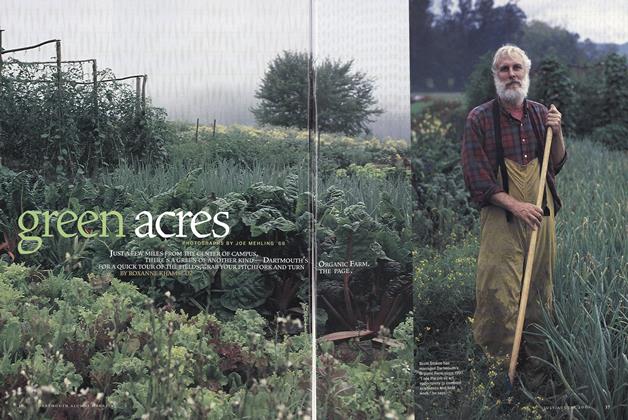

FeatureGreen Acres

July/August 2001 By ROXANNE KHAMST ’02