And that night you will talk with Major Gavilan in a whorehouse, with all your old comrades, and you will not remember what was said, or whether they said it or you said it, speaking with a cold voice that will not be the voice of men but of power and self-interest: we desire the greatest possible good for our country, so long as it accords with our own good; let us be intelligent and we can go far: let us accomplish the necessary, not attempt the impossible: let us decide here tonight what acts of cruelty and force are needed now to make it possible for us to avoid cruelty and force later: let us parcel out well-being, that the people may have their smell of it; the Revolution can satisfy them now, but tomorrow they may ask for more and more, and what would we have left to offer if we should give everything already? except, perhaps, our lives, our lives: and why die if we thereby do not live to see the beneficent fruits of our heroic deaths? . . . have a sense of destiny, we are young and we glitter with successful armed revolution.

The Death of Artemio Cruz

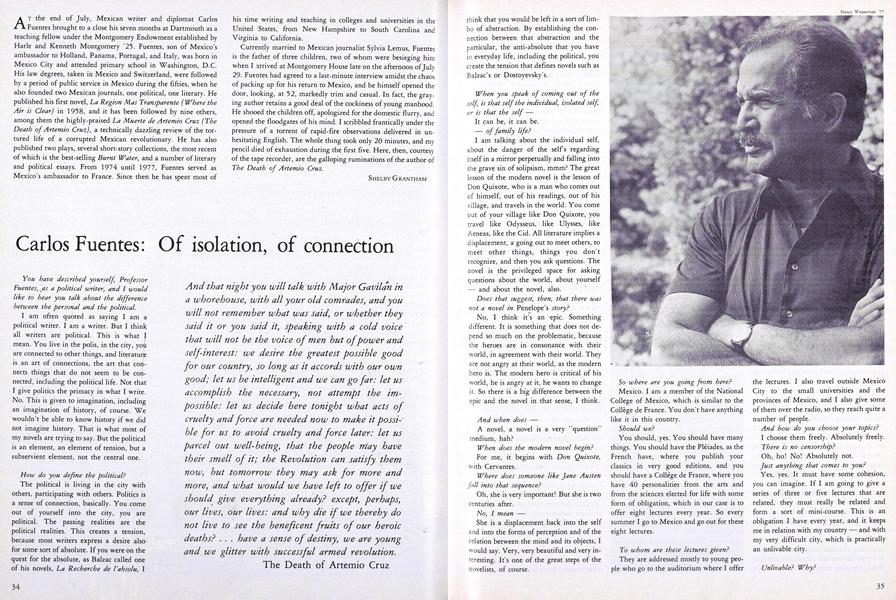

You have described yourself, ProfessorFuentes, as a political writer, and I wouldlike to bear you talk about the differencebetween the personal and the political.

I am often quoted as saying I am a political writer. I am a writer. But I think all writers are political. This is what I mean. You live in the polis, in the city, yoh are connected to other things, and literaturje is an art of connections, the art that connects things that do not seem to be connected, including the political life. Not that I give politics the primacy in what I write. No. This is given to imagination, including an imagination of history, of course. We wouldn't be able to know history if we did not imagine history. That is what most of my novels are trying to say. But the political is an element, an element of tension, but a subservient element, not the central one.

How do you define the political? The political is living in the city with others, participating with others. Politics is a sense of connection, basically. You come out of yourself into the city, you are political. The passing realities are the political realities. This creates a tension, because most writers express a desire also for some sort of absolute. If you were on the quest for the absolute, as Balzac called one of his novels, La Recherche de I'absolu, I think that you would be left in a sort of limbo of abstraction. By establishing the connection between that abstraction and the particular, the anti-absolute that you have in everyday life, including the political, you create the tension that defines novels such as Balzac's or Dostoyevsky's.

When you speak of coming out of theself, is that self the individual, isolated self,or is that the self It can be, it can be. of family life?

I am talking about the individual self, about the danger of the selfs regarding itself in a mirror perpetually and falling into the grave sin of solipsism, mmm? The great lesson of the modern novel is the lesson of Don Quixote, who is a man who comes out of himself, out of his readings, out of his village, and travels in the world. You come out of your village like Don Quixote, you travel like Odysseus, like Ulysses, like Aeneas, like the Cid. All literature implies a displacement, a going out to meet others, to meet other things, things you don't recognize, and then you ask questions. The novel is the privileged space for asking questions about the world, about yourself and about the novel, also.

Does that suggest, then, that there wasnot a novel in Penelope's story? No, I think it's an epic. Something different. It is something that does not depend so much on the problematic, because the heroes are in consonance with their world, in agreement with their world. They are not angry at their world, as the modern hero is. The modern hero is critical of his world, he is angry at it, he wants to change it. So there is a big'difference between the epic and the novel in that sense, I think.

And when does A novel, a novel is a very "question" medium, hah? When does the modern novel begin? For me, it begins with Don Quixote, with Cervantes.

Where does someone like Jane Austenfall into that sequence? Oh, she is very important! But she is two centuries after.

No, I mean She is a displacement back into the self and into the forms of perception and of the relation between the mind and its objects, I would say. Very, very beautiful and very interesting. It's one of the great steps of the novelists, of course.

So where are you going from here? Mexico. I am a member of the National College of Mexico, which is similar to the College de France. You don't have anything like it in this country.

Should we? You should, yes. You should have many things. You should have the Pleiades, as the French have, where you publish your classics in very good editions, and you should have a College de France, where you have 40 personalities from the arts and from the sciences elected for life with some form of obligation, which in our case is to offer eight lectures every year. So every summer I go to Mexico and go out for these eight lectures.

To whom are these lectures given? They are addressed mostly to young people who go to the auditorium where I offer the lectures. I also travel outside Mexico City to the small universities and the provinces of Mexico, and I also give some of them over the radio, so they reach quite a number of people.

And how do you choose your topics? I choose them freely. Absolutely freely. There is no censorship? Oh, ho! No! Absolutely not.

Just anything that conies to you? Yes, yes. It must have some cohesion, you can imagine. If I am going to give a series of three or five lectures that are related, they must really be related and form a sort of mini-course. This is an obligation I have every year, and it keeps me in relation with my country and with my very difficult city, which is practically an unlivable city.

Unlivable? Why?

Mexico City has 17 million people. Tremendous problems of communication. The most polluted city in the world. It is practically impossible to get from one place to another. The children are sick all the time. And personal communication breaks down as easily as physical communication.

In what way does personal communication break down?

People are isolated. They have no way of getting together. I will tell you, sometimes there are a young man and a young girl who meet at a party and fall in love, let's say. The young man says, "Where do you live?" The girl says, "I live in the south." He says, "Well, I live in the north. What a pity."

And they separate. They know it will be physically impossible for them to travel two or three hours in order to meet, because distances inside Mexico City are sometimes that great. The city is so sprawling, so big.

What is the area of the city?

Oh, it's a whole valley. It's immense. It's the most sprawling city in the whole world. It is going to be the biggest city in the world by the year 2000. It will have 30 million people.

Why is it growing so quickly?

Ohhhhh do you want to go into that? It's so complex. Immigration from the fields. Demographic explosion. The attraction of the city. Lack of opportunities in the countryside.

All the old 19th-century industrial revo4lution reasons.

But underlined by the factor of underdevelopment. The attraction is just too great for people who have very little in the countryside and think that in Mexico City they will make it. And it isn't so. They go into the slums. We have a great problem, a great problem, there, with the city, finding ways of making it an efficient, modern city.

Do you regard that as one of your tasksin life?

Oh, well, indirectly, indirectly. I write about the city a great deal. But I'm not a city planner, and I don't have official positions. I'm a writer and a teacher.

How do you see your relationship tostudents? What is pedagogy all about forsomeone who is principally a writer?

Well, writing is a very solitary occupation. Too solitary. It can become solitary in an almost uh deadly sense, in the sense that you lose touch with the world, that you fall into the solipsism that I have been criticizing, that you speak only to yourself or to your mirror and lose track of the world and especially of what young people are thinking and saying and being. I think a decent way to be in touch with young people is to teach. Besides, I learn a lot by teaching.

What things do you learn?

It forces me to organize my thoughts, to read many things that otherwise I wouldn't, to organize my knowledge, to take stock of myself, to. communicate not only what I know, but what I want to know, to make to an intelligent audience of young people the questions I am asking myself, and they will help me find answers.

You know, for me teaching is a very, very recent experience. Only since 1978. I had never taught before. I had always written or been in public service. When I resigned the Mexican ambassadorship to France in 1977, I received a series of invitations from universities in this country, and I accepted one from the University of Pennsylvania. That's where my experience began, and it has been an extraordinary experience, because I devote half the year really to teaching, along with my writing, and I come out very enriched by that. I meet very extraordinary young people. I worry about their destiny, what will become of them in our society. I get to understand your country much better. That is very important for a Mexican to go beyond the cliches we have about you, the same way you have cliches about us. But at Dartmouth, that experience has been enhanced by several factors, which I consider rather unique to this college.

The alumni will love that.

Well, they will love to hear what I have to say, because I think the student body is the best I have found anywhere, for the simple reason that it is an extremely interdisciplinary curiosity that animates it. Of 40 students that I had in my seminar on the identity of the Latin American novel, only 11 were majoring in literature. The other 29 came from biochemistry, from economics, from government, from history, from physics and this created a very interdisciplinary atmosphere in the classroom, which helped me enormously.

I can see time as a literary or historical element, but the students from physics bring in the notion of time from the point of view of science. Or a student from economics will bring in the concept of duration in economic terms, and so forth. It's the way the College is organized. The facility the students have for taking courses from disciplines other than the one they are majoring in gives it a very attractive dynamism, if I may say so. You know, to cap off my stay here, I offered five evening lectures during the month of July and was able to talk of subjects that interest me very much but that are as varied as relations between the United States and Mexico, the state of the novel today, the art of the cinema. A great, great variety, you see, of subjects I spoke about to groups of 30 to 35 undergraduates who came every Tuesday. This was enormously enriching for a writer.

Then there is the quality of the faculty, which I find very great. My wife and I have made very, very good friends here, lasting friendships, and we have been very enriched by them. My wife has audited many courses at the College, and I have listened both in private and in lectures to many of the members of the faculty, have taken notes like mad, have learned a lot.

And third, because of its isolation which is the thing that makes you fearful of coming to Dartmouth in the first place it generates its own cultural life. There were weeks when my wife and I said, listen, we can't go to the Hopkins Center every night for a different movie or theater or musical event. It's like living in Paris! We came here to study and write. Let's stop all these shenanigans!

So it's a very active center, it has its own personality, and it's very delightful. We've had an extraordinary time. And I must say how happy I am to have been a part of the Montgomery Program, because it represents the qualities I am praising in Dartmouth the interdisciplinary quality, the demands for connection, for relevance between the different zones of the knowledge of man.

And you find this different from whatyou found in other American universities?

Yes, sometimes because the universities are in enormous cities. This sense of intimacy, of getting to know yourself, of generating your own activity is lost in a big city like Philadelphia or New York. Or sometimes in other universities I find there is just too much specialization. There are gigantic barriers between the disciplines, and the students want it to be so or do not want to break them down. That.makes for a very narrow understanding of what you are teaching. I like to make many allusions when I teach to the cinema, to music, to politics, to journalism, to science, to things that connect literature with the world in which literature is produced.

"Only connect," as Forster says.

I adore that. I think connection is extremely important. I think isolation is death. There is a great phrase by William Styron in one of his novels "The wages of sin is not death, but isolation." That is worse than death. So I am very much against excessive specialization, mmm? I think the writer faces today tremendous problems of monopolization of the image and the word by the media or by political institutions.

How does that disturb the writer's task?

It disturbs it in the sense that you fear that there is a purpose to deprive the word itself of the sense of variety, doubt, criticism that has been associated with it throughout the glorious history of Western literature. Suddenly you seem faced in the capitalist West with prepackaged images and messages through the media, or in the Marxist East with prepackaged ideological jargon. So the necessity of the word allied to imagination (which is what literature is all about) is more important, more relevant than ever. You see, the cultures where the novel is thriving, where it is alive . . . well, I would say there are two great poles: the Americas, basically Latin America, and Eastern or Central Europe. These are the places that a writer feels that if he does not say things, nobody will say them. There the written word is all-important, because it is there to express the unsayable.

Many of the great American writers also understand this. Here you feel that almost insensibly there is a growing concentration of information in the media which, happily, is in democratic hands right now. But it could be otherwise some day. It could be otherwise, conceivably. And I think writers must foresee this. And think seriously of the problem it poses for more than the art of writing, for the art of communication and doubt and reflection and criticism and thought and knowledge.

What part does the academy play in this?

Ah. Well, I think the academy provides resources of information that are essential. The organization of libraries in this country and here let me put in a good word for Baker Library, more than a good word, a super word for Baker Library, where I have been able to work so magnificently for the past seven months. If we reached the Fahrenheit situation, you know, the uh, what is the name of your science fiction writer? Oh, Ray Bradbury the point of incineration of all books, then you would be totally in the hands of tyrannical powers. You would be immediately enslaved. So I think the university is a great center to assure that words shall not be incinerated, they shall not flare up in a Ray Bradbury situation.

But more than that I think the great mis- sion of universities today is to help different cultures understand each other. That is why I am so glad, as a Latin American writer, to be present here at Dartmouth. The great danger that we run is that in the age of instant communication, the different cultures are more separate from each other than ever. I remember my grandfather and my father's generation in Mexico receiving in Vera Cruz you know, by mailboat, transAtlantic the latest issues of the London Illustrated News, of Le Figaro, the latest novels from Paris or London. Today, you go to England and nobody knows what is happening in France. You go to France and nobody knows what is happening in the United States. You come to the United States and nobody knows what is happening in Mexico. You go to Mexico and nobody knows what is happening in Italy. The ignorance of the cultures is incredible. The space of communication has been filled by entertainment, by frivolity.

I think that the whole international political approach is that of recognizing the other, mmm? Which is the basis for peace. It is something that is born in the university, in the activity of the university. The university understands better than any other institution that culture is a way of relating to what is different from you. A way of relating to what is different from you. A way of of exorcising, if you wish, that horrible, animal, primeval urge some people have to annihilate, to destroy what is not like them. "Jew! Black! Communist! Yellow!" Whatever.

Do you think that is innate or accultured?

I think it's accultured. Most things are. But the university offers the other culture, the possibility of the other culture, of the humane culture, the civilized culture, the tolerant culture. It is acculturation, but it is a sort of simplistic acculturation, an acculturation of imbecility, or of stupidity. It is much easier because it is slothful, because it doesn't take any trouble to hate, to say, "I am different from you. You are different from me. I hate you." That is far too easy. It takes an effort sometimes, an effort to recognize ourselves in what is different from us. That is a great thing for a university or a college to understand as part of its function, because it applies not only to individuals, but also to nations and cultures.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryJust a suggestion, Mr. President: an agenda for the eighties

October 1981 -

Feature

FeatureSubmariner

October 1981 By M. B. R -

Article

ArticleDeaths

October 1981 -

Article

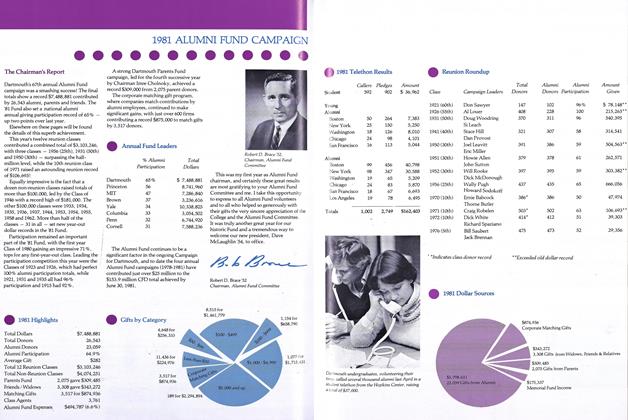

Article1981 ALUMNI FUND CAMPAIGN

October 1981 -

Article

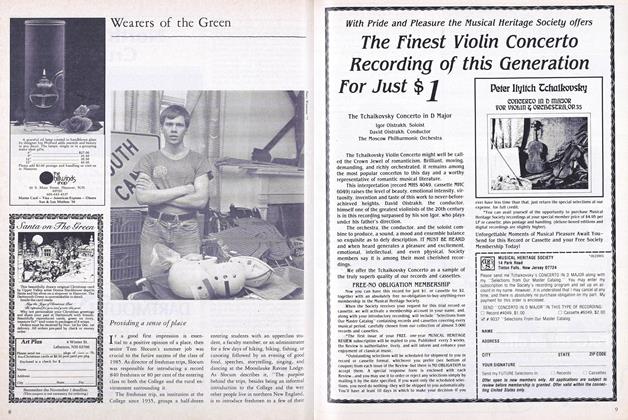

ArticleWearers of the Green

October 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

October 1981 By Michael H. Carothers

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCHARLES WHEELAN '88

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Feature

FeatureAN ATHLETIC SUMMING UP

JUNE 1967 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe Greatest Issue: Self-Fulfillment

July 1962 By JAMES T. HALE '62 -

Feature

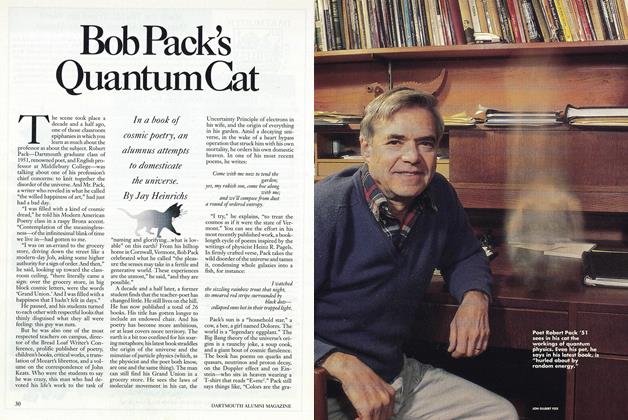

FeatureBob Pack's Quantum Cat

December 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureMILITARY POWER: THE FADING PERSUADER

OCTOBER 1966 By LIEUTENANT GENERAL JAMES M. GAVIN -

Feature

FeatureThe Human Revolution and World Peace

May 1961 By RICHARD W. STERLING