A Sunday in December 40 years ago

FOR many people living in Hanover, the day had deeper significance than any other in their lives. Only the moment of birth would have more effect on the condition of their stay on earth. For a few, it was the beginning of the end; for nearly all the end of the beginning. It was, in some ways, an ordinary Sunday in December, but events 6,000 miles away signaled a complete change in outlook, an abrupt awakening, a dramatic introduction to realities of conflict. In the casual, sheltered dormitories and leafy academic surroundings a way of life was soon to be uprooted. The cleanshaven, short-haired, lusty young men cynics or idealists, team players and individualists would be transported beyond their control or their imagination. Within the next five years they would come to learn the precise meaning of "the luck of the draw."

Many would eventually bring their experiences back to Hanover. Some would never return. They would suffer fatal training accidents, take bullets as they hit the beaches, fall from the sky, or perish in PW camps. There were many ways to die. Eventually, their names would be incised on a polished granite plaque, situated on the wall of a building they never saw, in a place that people seldom visit the back porch of the Hopkins Center snack bar.

As the bells of Baker clanged 10:00 a.m., sleepers still occupied most beds in the dormitories and fraternity houses. Only a few committed students were up and around that overcast morning. Breakfasters at Thayer Hall numbered fewer than the help. The skies were slate gray and unappealing. A trace of snow covered the ground, left over from Saturday's flurries. There was the threat of a little more. The air was jacket-chilly but not cold enough to produce skateable ice at Davis Rink, a fact that frustrated Eddie Jeremiah. The hockey coach had been hustling his players from ponds to local prep schools in an effort to get them ready for a season that would include a western trip over Christmas vacation and warm-ups at home against M.I.T. and Norwich. The sophomore line of Riley, Harrison, and Rondeau (all '44) had shown remarkable promise as yearlings. Jeremiah was anxious to see them in varsity league play. But the lack of artificial refrigeration and mild weather was pushing his patience. His captain, Ted Lapres '42, needed work in the nets, and he couldn't get it on Occom Pond.

A scattering of Catholic students were on their way to St. Denis's. They cut through South College, a street that disappeared when Hopkins Center was built, to the church on Lebanon Street where they heard Father Sliney read the gospel according to Saint Matthew and deliver his sermon. There were also services at Rollins Chapel, the White Church, and St. Thomas's Episcopal on West Wheelock. None drew as many students as a Hedy Lamarr movie called Ecstasy.

The basketball varsity had already played some scrimmages, and George Munroe and Jim Olsen, both '43, had demonstrated to Coach Ozzie Cowles that they could make outside shots. The squad was captained by Stubbie Pearson '42, a 6-foot 3-inch Minnesotan of remarkable achievements. Pearson, also a three-season football letterman, had led the (then) Indians through a 5-4-0 gridiron season. The amazing Pearson was also Phi Beta Kappa, class valedictorian, and a Senior Fellow interested in political science. He had been class president for three years. In a surprise vote on December 4, the class of 1942 had elected Dale Bartholomew as its senior president- During the same week, Whitey Meigs '43 had been elected future captain of the soccer team, and Bob Williams '43 was picked to lead the cross-country runners.

The ski coach, young Percy Rideout '40, had replaced Walter Prager, a native of Austria, who had enlisted early as a corporal in the Army Ski Battalion. Rideout was working with a blue-eyed, blond, and rangy senior, Jake Nunnemacher, his team captain. The first meet was scheduled for December 20 at Franconia.

Early in the week, Lewis Mumford, the philosopher, was on campus to speak to classes and give an evening lecture. "One of the sad things about America," Mumford told the students, "is that its memory is short there is a lack of continuity between generations. Many of the men written about in the American Caravan were great writers in the 1920s but their importance has vanished all that is left is memories the editors hold of the men. '

And Europe was on fire. Hitler's armies had rolled almost parade fashion through Norway. The Netherlands, Belgium, and France fell as quickly. Now, in December, the Germans were within striking distance of Moscow. At Dartmouth's convocation earlier in the fall, President Hopkins had talked to the students about the menace, saying, with peculiar indirectness, "When preponderantly among the peoples of the earth, might reigns and gives its own perverted definition as to what constitutes right, at such a time right, as defined by the mind and conscience of man through the ages, must oppose with greater might, if it is to survive." This was not exactly a call to arms. The address was entitled "The Probability of the Impossible."

THE prevailing mood in Hanover was one of conscious, maybe even nervous, anticipation. Surely, there were both anxiety and a sense of helplessness. For some there was, indeed, an escape hatch showing a little crack of light, a way to chuck it all, with honor. It was vague but not wholly foreboding. A number of seniors and juniors had already registered for the draft but were given time to finish college. Still others had chosen to leave school and enlist, usually in the Army or Naval Air Corps, but some joined the Marine Corps or the Royal Canadian Air Force via Montreal. Dropping out just one or two at a time, these departures were nevertheless widely noted. A few Chi Phis of '42 had joined their '41 classmates, who had already graduated, in what was to be a Dartmouth Naval Air Training Unit at Squantum, Massachusetts.

A Dartmouth student poll, taken in October by The Dartmouth, showed that 284, or one-third of the students who responded, favored the United States going immediately to war against Germany. The same question asked in 1940 showed only 75 students with that answer. A Gallup poll, taken in mid-November as an intercollegiate survey, suggested that Dartmouth students led the nation in willingness to go to war." The conclusions were somewhat shaky, but the point seems to have been that eastern students were more involved than midwesterners and Dartmouth more aggressively interested than other schools.

But, like students in Ann Arbor or Columbus, undergraduates in Hanover were not wholly preoccupied with the war. On Saturday night, December 6, the Nugget Theater, then located on Wheelock Street behind Casque and Gauntlet, played to a rowdy student house, at 35 cents a head. The show: Nine Lives Are Not Enough, starring Robert Preston and Ellen Drew.

It was an off-weekend. Many rides had left at noon to go over the mountain to Saratoga Springs and Skidmore or down Route 5 to Northampton, Smith, and Rahar's, the roomy five-cent-hard-boiled egg and fifteen-cent-beer tavern. Alex Fanelli and Jerry Tallmer, both '42, figured it was to be a quiet weekend so together they rented a car from another student for five dollars and drove to Wellesley where they had late Saturday night dates. Tallmer was editor-in-chief of The Dartmouth and Fanelli was editorial chairman.

The hockey game with Norwich was cancelled because the ice was too soft and not enough of it. A concert by the Rochester Philharmonic and Jose Iturbi was delayed, and Slim from Tanzi's delivered a number of kegs to fraternity houses where brothers pooled their resources and chipped in for the beer. There were the usual armwrestling matches, bull sessions about women, and guzzling "crew" races among the mostly male crowd. The late-stayers sang "Bridget O'Flynn," "We'll Build a Bungalow," and "The Fireman's Ball." Two girls in saddleshoes from Colby Junior hung around and tried to teach Minnie the Mermaid" to a confused sophomore who only wanted to sing "Minnesota, Hats Off to Thee." It was Saturday night.

SUNDAY was intended as a respite, a time to charge up for the impending exams. A few late risers, some wearing their green 1943 numeral sweaters, unpressed gray flannels, and dirty white buck shoes strolled down to the quiet Main Street. They could buy an ice-cream cone at Allen's or the New York Times at Putnam's Drug Store or check out Fletcher's, which was closed. They could peek into the store windows and see skis with steel edges and bindings, complete for $15.50, at Art Bennett's. Button-down Manhattan shirts at Campions sold for $2.50. By noon, it was time for either the stacks in Baker or the radio.

The radios in the dormitories functioned as magnets. For the New York crowd, attention centered on a broadcast of the New York Giants Brooklyn Dodgers professional football game. When the broadcast began, a group stretched out in a smoky room in the basement of Middle Fayerweather learned that a capacity crowd of 55,051 had filled the Polo Grounds. The horizontal lower-floor gathering did have some athletic sophistication. Many had played high-school or prep-school football. They knew that Bill Hutchinson, Dartmouth '40, was on the Giant squad, and they understood the single wing. The quarterback blocked and halfbacks passed and ran. Fullbacks slammed through the line and played linebacker on defense. It was an era of 60-minute performances.

It didn't take the Dodgers long to prove that their motivation was stronger than that of the Giants, champions of the Eastern Division. They not only gained an early lead, they sent the previously indestructible Giant captain, Mel Hein, off to the hospital. The announcer described it as no contest. There was, however, an interruption during the broadcast for an important news bulletin. In their ignorance, neither the announcer nor his listeners were initially certain of its reality or significance.

AT dawn, the voice on the radio said, Japanese planes had come in over the island of Oahu and bombed Pearl Harbor, a Naval installation in the territory of Hawaii. In addition, low-flying Zeros with Japanese markings had strafed and bombed an Army air base called Hickam Field. As more bulletins came in, the game became less and less significant. American casualties were said to be high. Word leaped across the campus like news of, well, like news of a war.

Andy Caffrey '43 was in Baker Library studying for a political science exam. Someone said out loud, "The Japs bombed Pearl Harbor." Caffrey's line was repeated so many times across America that it has now become a classic: "Where's Pearl Harbor?"

Bad news has fast legs. The town of Hanover changed its sleepy Sunday afternoon character. Someone with a keen sense of history caused the bells of Baker to ring out patriotic melodies. Flags appeared on the residences as if by decree. Somehow, the stripes of red looked redder, the whites looked more pure, and the 48 stars stood out against the blue field more clearly than ever before. Even the dogs moved cautiously, but quickly, in packs. Steve Flynn '44 and Bill Mitchel '42 rushed to man the newly formed Dartmouth Broadcasting System control room in lower Robinson Hall. It was their first crisis, and they made a gutsy effort to piece together the teletype news and get on the air in some reasonable, logical fashion. They had the audience.

Tallmer and Fanelii had stayed with friends at Harvard, overnight but returned to Hanover early that Sunday afternoon. They were in the offices of The Dartmouth assembling Monday's issue when they heard the news. Both men had worked on the paper's extra edition at the time of the Dartmouth-Cornell Fifth Down drama in 1940. The thought of another extra occurred to them almost simultaneously. They gathered their forces and went to work. Jim Farley and Craig Kuhn, both '42, pieced together what sketchy information was available. At first, it was thought that the Japanese had bombed Manila along with Honolulu. Joe Palamountain '42 hammered out a thoughtful editorial in line with The Dartmouth's position as outlined by Tallmer. It was a heady evening punctuated with coffee at George Gitsis' Campus Cafe, located a few doors away from the Dartmouth Printing Company on Main Street, There was an extra to get out; moreover, the composition of the Monday, December 8, issue had to be thoroughly revised to adjust to the war facts. No other information was really vital to young men 20 or 21 years old.

By 8:21 p.m. the seasoned staff had the extra on the streets of Hanover. Headline: JAPS DECLARE WAR ON U.S. SHOOTING BEGINS. It was a single sheet printed on both sides. President Roosevelt's picture was on the front page. Palamountain's editorial was headed "Now It Has Come." Essentially, it expressed relief that the waiting was over. Its final line: "And so, as we enter this fight for our life, we thank the Japanese for enabling us to enter a united people."

In his dormitory, Bob Craig '43, a Honolulu resident for 15 years, became a reservoir of information. He described the situation as "inconceivable," adding, "the Navy is supposed to maintain a 200-mile patrol around the harbor."

Takanobu "Knobby" Mitsui '43 lived in Massachusetts Hall. He was a member of one of the leading Japanese families. He talked that evening with Dean Lloyd Neidlinger and decided to remain in school, cabling his parents that he was "in no personal danger and would finish college.

In the basements of fraternities, friends viewed each other with a new sense of evaluation. Decisions were made and remembered. The thought of "soldiering with this one or that one was often based on past performances on the athletic field, a ready means of measuring physical courage, wit, resourcefulness, and endurance.

By Monday, the chaos of the weekend had begun to be sorted out, President Roosevelt and Congress declared war on both Japan and Germany. The call to arms had sounded. On the following Wednesday, December 10, the editors of The Dartmouth demonstrated leadership as good as their word. Both Fanelli and Tallmer left school to enlist. They were two of many.

OTHERS on campus worked things out. They congregated and talked and, together and alone, searched their souls. They called home when they could get to a phone, and sometimes they called girls. They drifted away from Hanover, one by one, or they made deals with the Army and Navy, gaining a little time. By December of 1942 the Navy had commandeered the Dartmouth campus and others as well. Whoever was left went on assignment, in uniform - to Notre Dame, Columbia, Quantico boot camp, Fort Dix, Squantum, Randolph Field.

They would soon enough find themselves among new companions, packed in troop trains and ships, some destinations so foreign as to be completely unknown. Many would fly for the first time in their lives. Months later they would pilot four-engine bombers across the North Atlantic in groups of one hundred. Systematically they would arrive in faraway places with strange sounding names. They would discover red tape, symbolism, volley ball, boredom, steel helmets, raw courage, ingenuity, firepower, V-mail, and girls who did not speak or understand English. Some ultimately would hear English and be unable to understand it. On occasion they would find each other again in the noisy snake pits and jukebars of San Francisco, in the grimy pubs of London, on the sun-baked coral runways of tiny Pacific atolls, in freezing Quonset huts in the Aleutians, on the busy decks of massive gray carriers. They would come to know the sights and sounds of kamikaze and the shattering blast of Browning Automatic Rifles. They would bellow "Dartmouth's In Town Again" in cafes of the Montmartre, and pray to Michael the Archangel as they were dropped across the Rhine. And some would shout "wah-hoo-wah" on the intercom, 18,000 feet above the Ruhr Valley. Still others would do white-collar clerical work, struggling at cryptography or statistical profiles in little offices around Washington, at Brooklyn Navy Yard, or in Dayton, Ohio. It was the game of American roulette, and there were losers and winners. With it all there was a euphoric sense of adventure, a taste of vertical and horizontal travel, even though the price of the tickets was high.

The momentous events of the next few years would bring death and sorrow, love and joy, honor and glory. The memories of what happened before and after that fateful Sunday are in sharp focus because the men of the time fulfilled a tradition that cannot be denied. They signed up and took their chances.

People had, reasonably, predicted that the promising political science major, Stubbie Pearson, would some day be governor of Minnesota at least. He died piloting a dive bomber in an attack on a Japanese cruiser off the Palau Islands. Both Stan Wright '42 and Ambie Broughton '43, of the hockey team without December ice, died in the sweltering Pacific. Wright was a Marine, shot moving in on Tarawa, Broughton, co-pilot in a B-24, on a bomb run. Jake Nunnemacher, with the 10th Mountain Division, was mortally wounded in the mountains of Italy. John Smith 43 was killed in action, on December 7, 1944, in the Philippines. There were many others.

At graduation, Pearson had said in his valedictory to the class of 1942: "This is the war for the future. Man must replace the importance of material gain. We must humanize ourselves. Man is man and that is all that is important. ... Do not feel sorry for us. We are not sorry for ourselves. Today we are happy. We have a duty to perform and we are proud to perform it."

Dartmouth went off to war and the war in the form of the Navy V-12 - came to Dartmouth.

Stubbie Pearson's future seemed golden. "Do not feel sorry for us, he said.

Eddie O'Brien '43 served more than fouryears in both the Pacific and the EuropeanTheaters of War but saw little combat withthe Air Transport Command.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Now we had to go in different directions"

November 1981 By Rob Eshman -

Feature

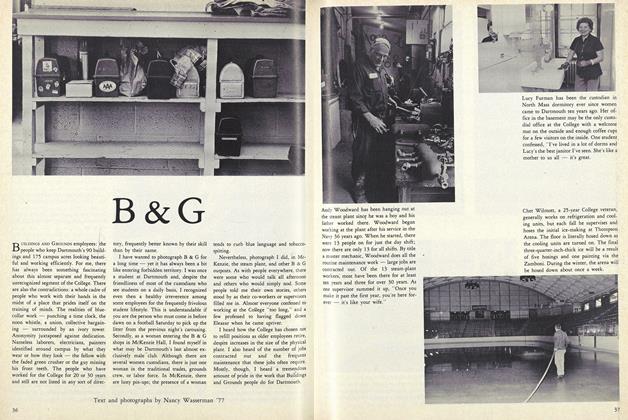

FeatureB & G

November 1981 -

Article

ArticleMaster Carpenter, Journeyman Blackmailer

November 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

November 1981 By William G. Long -

Class Notes

Class Notes1961

November 1981 By Robert H. Conn -

Class Notes

Class Notes1965

November 1981 By Robert D. Blake

Features

-

Feature

FeatureIs Vietnam Still Claiming Some of Us?

December 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureWarner's 41 Dramatic Years

MAY 1969 By MARGARET BECK McCALLUM -

Feature

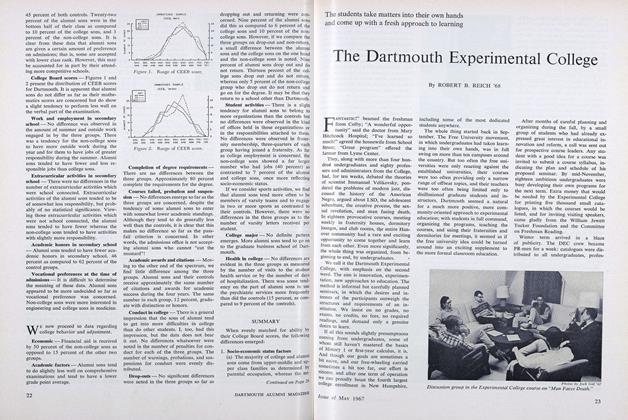

FeatureThe Dartmouth Experimental College

MAY 1967 By ROBERT B. REICH '68 -

Cover Story

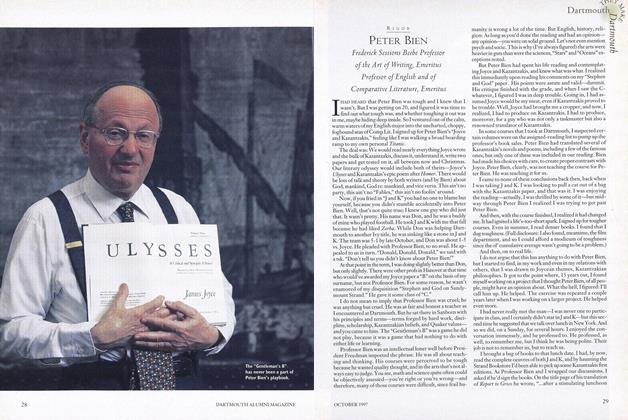

Cover StoryPeter Bien

OCTOBER 1997 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureFinal Assembly

October 1951 By SIR HAROLD CACCIA -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBusted By the Cryptic

MARCH 1995 By Valerie Frankel '87